Vaccine Injury and State Responsibility in Japan: The Otaru Smallpox Case and the Presumption of Contraindication

Judgment Date: April 19, 1991

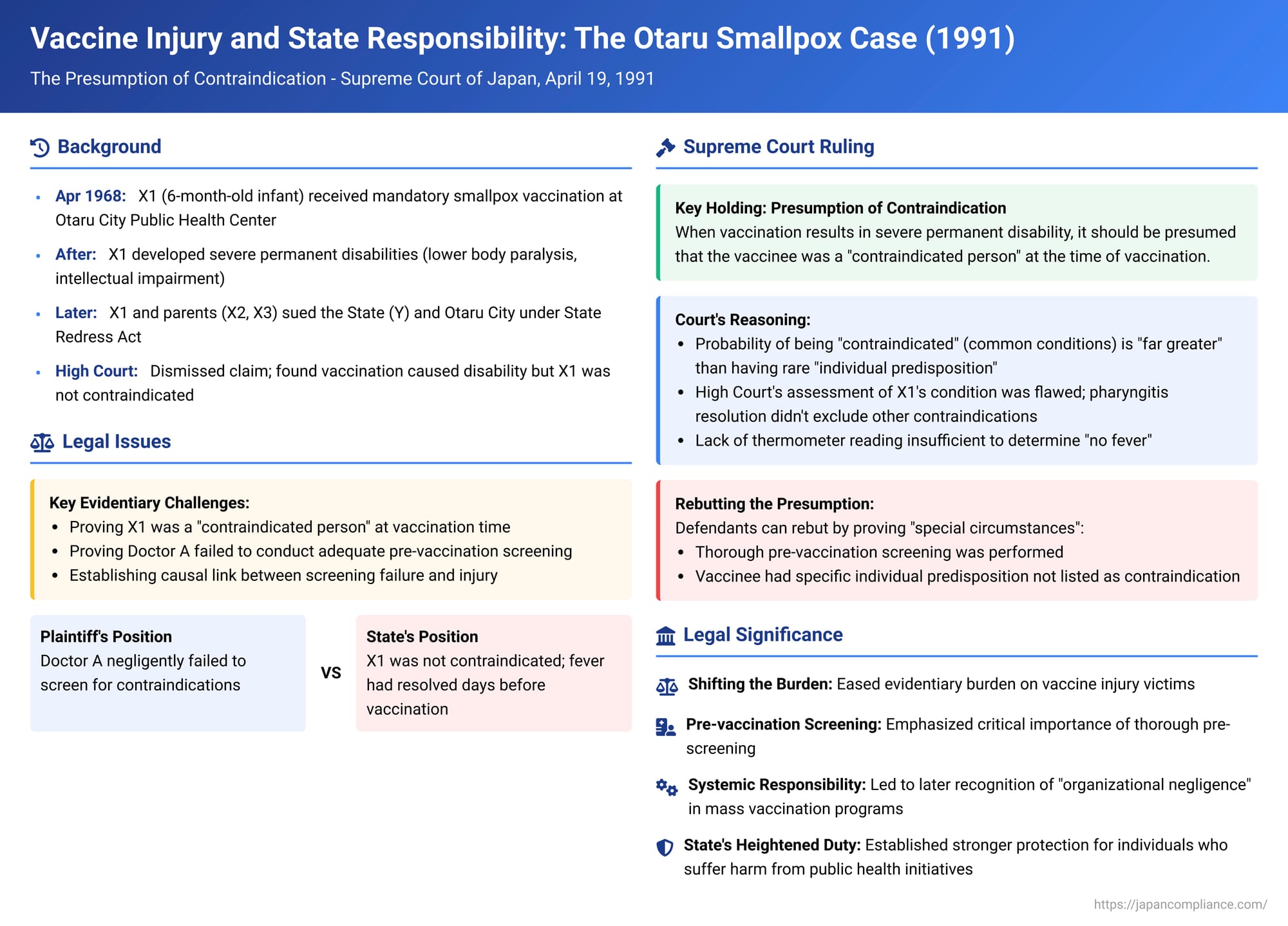

Public vaccination programs are a cornerstone of modern public health, designed to protect populations from infectious diseases. However, in rare instances, individuals can suffer severe and lasting adverse reactions to vaccines. When such tragedies occur, especially following mandatory or strongly promoted state-run immunization programs, complex legal questions arise regarding causation, negligence, and the responsibility of the State. The "Otaru Smallpox Vaccination Incident Case," culminating in a Supreme Court of Japan (Second Petty Bench) judgment on April 19, 1991 (Showa 61 (O) No. 1493), is a landmark decision that significantly addressed the evidentiary challenges faced by victims in seeking compensation from the State, particularly by establishing a crucial legal presumption.

The Otaru Smallpox Vaccination Incident: A Tragic Outcome

The case involved X1, who, as a 6-month-old infant in April 1968, received a smallpox vaccination at the Otaru City Public Health Center. This vaccination was administered under Japan's then-mandatory Immunization Act (予防接種法 - Yobō Sesshu Hō). The vaccine was given by Doctor A, the Chief of the Prevention Division at the health center.

Following the vaccination, X1 developed severe and permanent disabilities, including lower body paralysis resulting in motor impairment, and intellectual impairment. X1, along with his parents X2 and X3, subsequently filed a lawsuit seeking damages. The primary defendants in the appeal to the Supreme Court were the State of Japan (Y) and Otaru City. The claim against the State was based on Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the State Redress Act (国家賠償法 - Kokka Baishō Hō), alleging that the State, which had delegated the immunization task to the Mayor of Otaru City, was liable for the negligence of the public officials involved. The claim against Otaru City was based on Article 3, Paragraph 1 of the same Act, as the entity responsible for the salaries of Doctor A and Director B (the head of the health center).

The core allegation of negligence was that Doctor A had failed to conduct an adequate pre-vaccination screening (予診 - yoshin) to determine if X1 had any contraindications to the vaccine, and that Director B had failed to ensure that proper procedures for such screenings were in place and followed. (Claims against Doctor A, Director B personally, and the vaccine manufacturer had been dismissed at the first instance and were not part of this appeal.)

The Evidentiary Challenge: Proving Negligence and Contraindication

Vaccination injury cases often present significant evidentiary hurdles for plaintiffs:

- Medical Uncertainty: The precise medical mechanisms behind rare, severe adverse vaccine reactions are not always fully understood. Sometimes referred to as the "devil's lottery" (悪魔の籤引き - akuma no kujibiki), these reactions can occur even when a vaccine is properly manufactured and administered.

- Proving Contraindication: It can be difficult, years after the event, to definitively prove that a child was a "contraindicated person" (禁忌者 - kinkisha)—i.e., had a specific health condition listed in the official guidelines that should have precluded vaccination at that particular time.

- Proving Negligent Screening: Demonstrating that the pre-vaccination screening conducted by the doctor was inadequate or fell below the required standard of care can also be challenging, especially with limited records or fading memories.

The Sapporo High Court (second instance) had dismissed the plaintiffs' claims. It found that while X1's disabilities were caused by the vaccination, X1 was not a contraindicated person at the time of the shot. The High Court noted that X1 had developed a pharyngitis (sore throat) with a fever of 38.8°C five days before the vaccination. However, his temperature had returned to normal at least two days before the vaccination, and there was no fever on the morning of the vaccination. The High Court thus concluded that the pharyngitis had resolved and X1 was fit for vaccination. Therefore, even if there were deficiencies in the pre-vaccination screening, the High Court reasoned that the vaccination itself was justified and there was no causal link between any alleged screening inadequacy and the subsequent harm.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: Introducing the Presumption of Contraindication

The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Court's judgment introduced a significant legal presumption to aid plaintiffs in overcoming the evidentiary difficulties in such cases.

- Causation Between Vaccination and Injury Accepted: The Supreme Court did not disturb the lower court's finding that X1's severe disabilities were, in fact, causally linked to the smallpox vaccination he received. The Court acknowledged the high probability of this link based on the clinical progression of X1's condition.

- The Rationale for the Presumption: The Court then considered the likely causes when a vaccination results in severe, permanent disability:

- (a) The vaccinee was a "contraindicated person": The child had a health condition listed in the official Immunization Implementation Rules (a Ministry of Health and Welfare ordinance under the Immunization Act) that should have precluded vaccination at that time. These listed contraindications typically included conditions like acute febrile illness, certain chronic diseases, or known allergies.

- (b) The vaccinee had a rare "individual predisposition" (個人的素因 - kojinteki soin): The child had some unusual, perhaps unknown, individual susceptibility that made them react severely to the vaccine, even if they did not fit any of the listed contraindications.

The Supreme Court reasoned that the conditions listed as contraindications are generally common illnesses or states that can affect ordinary people. Therefore, the probability of any given individual falling into one of these contraindicated categories is "far greater" than the probability of them possessing a rare, unidentifiable individual predisposition to a severe vaccine reaction.

- The Presumption Established: Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court established the following rule:

When a vaccination results in severe permanent disability, it should be presumed that the vaccinee was a "contraindicated person" at the time of vaccination, and that the disability occurred because of this contraindication.

This presumption effectively means that if a causal link between the vaccination and the severe injury is established, the court will assume the child should not have been vaccinated due to their health state at the time. - Rebutting the Presumption: This presumption is not absolute and can be rebutted by the defendant (the State or administering authority) if they can prove "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō), such as:

- (a) A thorough pre-vaccination screening, as required by the regulations, was indeed performed, and no contraindicating conditions were discovered. This would involve proving that the doctor diligently followed all prescribed screening procedures.

- (b) The vaccinee is proven to have had a specific individual predisposition (not a listed contraindication at the time) that was the true cause of the severe reaction.

- Critique of the High Court's Assessment of X1's Condition:

The Supreme Court found the High Court's determination that X1 was not contraindicated to be flawed:- "Pharyngitis" is merely a symptom (inflammation of the pharynx). Its apparent resolution (e.g., subsidence of fever) does not necessarily mean that the underlying illness causing it (which might itself be a contraindication) had fully resolved, nor does it exclude the possibility of other co-existing illnesses that could be contraindications.

- The High Court's finding that X1 had "no fever" on the day of vaccination was based on the mother's (X3's) general observation, not on a thermometer reading. The Supreme Court deemed this insufficient to definitively conclude X1 was free of fever, which was a key contraindication.

- Given these weaknesses, the Supreme Court stated that the facts established by the High Court did not permit a definitive conclusion that X1 was not a contraindicated person.

- Error of the High Court and Reason for Remand:

The High Court had dismissed the plaintiffs' claims of negligence in the pre-vaccination screening by concluding X1 was fit for vaccination. The Supreme Court ruled this was an error. In light of the newly established presumption, the High Court should have first thoroughly examined whether Doctor A had conducted an adequate pre-vaccination screening sufficient to identify any contraindications. The case was therefore remanded for the Sapporo High Court to re-examine this crucial issue, now with the burden effectively shifted regarding X1's contraindicated status.

(Outcome on Remand: The Sapporo High Court, upon retrial (judgment December 6, 1994), acknowledged the presumption. After considering factors like X3's own slight lack of due care (contributory negligence assessed at 10%) and deducting amounts already received under the statutory vaccine injury compensation scheme, it found the State and Otaru City liable for damages.)

Impact and Significance of the Otaru Smallpox Ruling

The Supreme Court's 1991 Otaru judgment had a profound impact on vaccine injury litigation in Japan:

- Easing the Evidentiary Burden on Victims: The most significant impact was the easing of the often-insurmountable burden of proof on victims. By presuming that a severe adverse reaction implies the vaccinee was contraindicated, the Court shifted the focus of the legal inquiry towards the adequacy of the pre-vaccination screening conducted by the medical personnel. Plaintiffs no longer had to definitively prove they were contraindicated; rather, the State had to show a proper screening was done that found no such issues, or that a rare, unlisted predisposition was to blame.

- Building on Earlier Precedents Favoring Victims: This decision built upon an earlier Supreme Court ruling from 1976 concerning an influenza vaccine (which was then "recommended," not mandatory like smallpox). In that 1976 case, the Court had held that if a doctor failed to conduct an adequate pre-vaccination screening and vaccinated a contraindicated person, and an adverse reaction followed, the doctor's negligence (specifically, the foreseeability of harm) would be presumed unless the State could prove specific exonerating circumstances. The Otaru judgment reinforced this protective stance by making it easier to establish the prerequisite fact that the individual was contraindicated in the first place.

- Focus on Systemic Responsibility ("Organizational Negligence"): As noted by legal commentators, the principles established in the 1976 and 1991 Supreme Court rulings paved the way for subsequent High Court decisions in other mass vaccination lawsuits (e.g., related to polio, MMR vaccines) to find the State liable for "organizational negligence" (組織過失 - soshiki kashitsu) or "systemic fault" (システム形成責任 - shisutemu keisei sekinin). This broader concept of negligence looked at failures in the State's overall design and implementation of mass immunization programs, such as setting unrealistic quotas for doctors (too many vaccinations per hour, hindering proper screening), failing to provide adequate information and warnings about risks to both medical professionals and the public, and strongly promoting vaccinations for public defense without sufficiently addressing individual safety.

- State's Heightened Duty in Public Health Initiatives: The judgment underscores the heightened responsibility of the State when it implements public health programs, like mandatory or strongly encouraged vaccinations, which inherently carry risks for a small minority of individuals for the benefit of the wider community. The courts showed a willingness to interpret legal duties in a way that provides recourse for those who suffer such "special sacrifices."

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1991 judgment in the Otaru Smallpox Vaccination Incident Case was a landmark decision in Japanese state liability and public health law. By establishing a legal presumption that a severe adverse reaction following vaccination implies the recipient was a "contraindicated person" (unless proven otherwise by the State), the Court significantly eased the burden of proof for victims seeking compensation. This ruling, alongside earlier related precedents, highlighted the critical importance of thorough pre-vaccination screening and contributed to a broader legal recognition of the State's systemic responsibilities in ensuring the safety of national immunization programs. It stands as a testament to the judiciary's role in balancing public health objectives with the protection of individual rights and the provision of redress for unavoidable harm incurred in the pursuit of collective well-being.