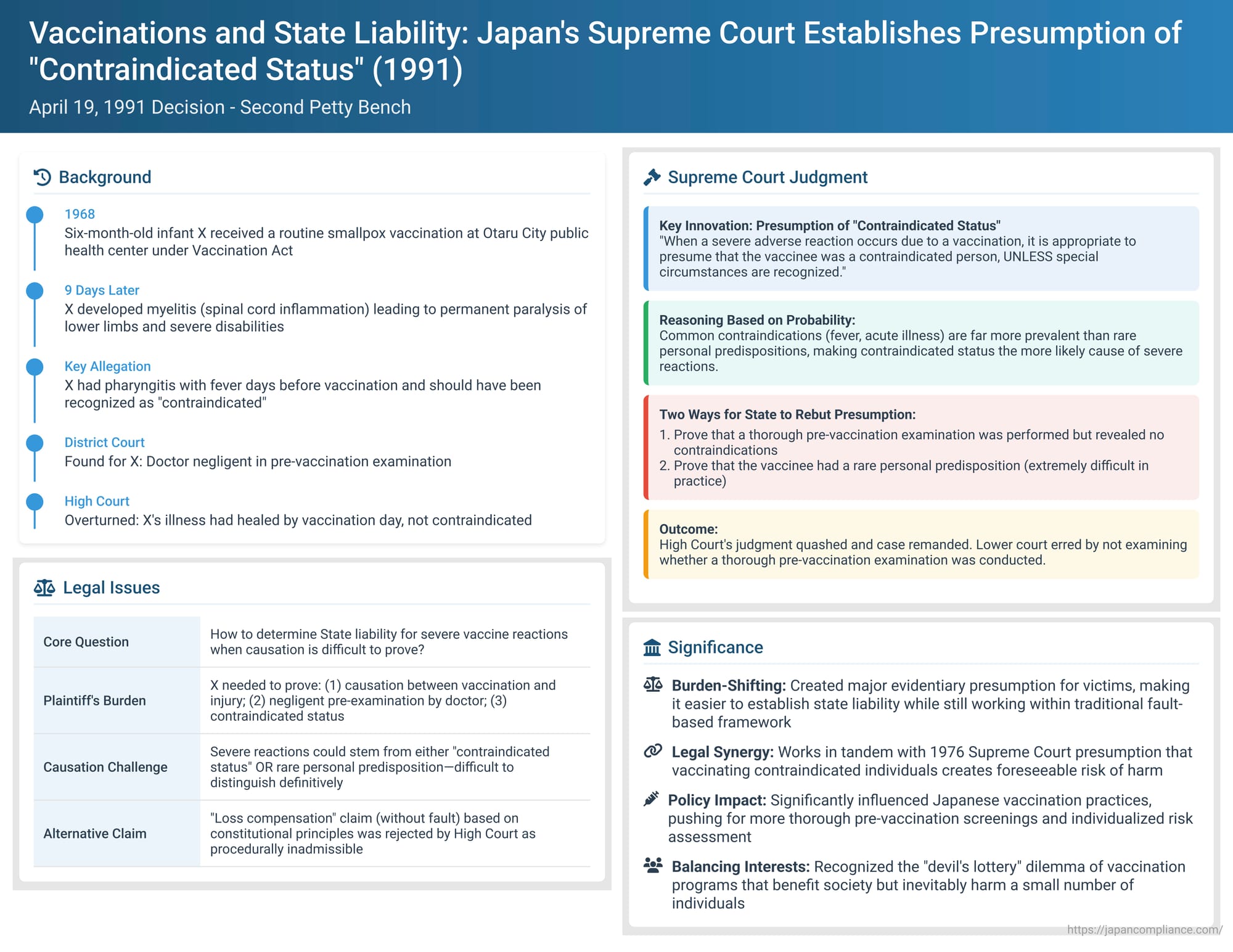

Vaccinations and State Liability: Japan's Supreme Court Establishes Presumption of "Contraindicated Status" in Adverse Reaction Cases

Date of Judgment: April 19, 1991

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

On April 19, 1991, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark judgment in a deeply concerning case involving a child who suffered severe and permanent disabilities following a routine smallpox vaccination administered under a public health program. This decision addressed the challenging legal questions surrounding state compensation liability when such adverse reactions occur. The core issues revolved around the adequacy of pre-vaccination medical checks and the formidable burden of proof faced by plaintiffs in establishing causation and negligence against the state. The Supreme Court's ruling was highly significant as it established a crucial evidentiary presumption in favor of vaccine-injured plaintiffs regarding their "contraindicated status" at the time of vaccination, an approach that markedly impacted the state's liability in such tragic cases and influenced subsequent public health policy.

I. The Tragic Outcome of a Routine Vaccination

The case began with a standard public health intervention that unfortunately led to devastating consequences for a young child and his family.

The Vaccination:

In 1968, X, who was then a six-month-old infant, received a routine smallpox vaccination. This vaccination was administered at a public health center located in Otaru City, Hokkaido, and was carried out under the provisions of Japan's then-existing Vaccination Act, which mandated or strongly recommended such immunizations as part of national public health policy.

Development of Severe Adverse Reaction:

Approximately nine days after receiving the smallpox vaccination, the infant X began to develop symptoms of myelitis, a serious inflammation of the spinal cord.

Permanent and Severe Disabilities:

The myelitis progressed and resulted in severe and permanent disabilities for X. These included the paralysis of both of his lower limbs, as well as significant and lasting impairments in his sensory perception and overall physical and cognitive development.

The Plaintiffs' Allegations and Legal Claim:

X (represented by his parents) and his parents themselves initiated a lawsuit against Y (a collective term used here to refer to the State of Japan, Hokkaido Prefecture, and Otaru City, as these governmental entities were variously responsible for the public health service and the administration of the vaccination program). Their primary legal claim was for monetary damages, brought under Article 1, paragraph 1 of Japan's State Compensation Act.

The core of their argument was that X had been unwell shortly before the scheduled vaccination; specifically, they alleged that he had suffered from pharyngitis (inflammation of the throat) and had experienced a fever a few days prior to the vaccination appointment. Due to this pre-existing, albeit recent, illness, they contended that X should have been medically recognized as a "contraindicated person" (kinki-sha) on the day the shot was administered. A "contraindicated person" is an individual for whom a particular medical procedure, such as vaccination, is medically inadvisable due to a condition that increases the risk of adverse reactions. They further alleged that this critical health status was overlooked by the medical staff at the public health center because the doctor responsible conducted an insufficient or inadequate pre-vaccination medical examination (yoshin).

II. The Legal Battle Through Lower Courts

The plaintiffs' quest for compensation involved a protracted legal journey through Japan's lower courts, with differing outcomes at each stage.

Sapporo District Court (First Instance):

- The Sapporo District Court, acting as the court of first instance, found in favor of X and his parents. The court determined that there was a sufficient causal link between the smallpox vaccination X received and his subsequent development of myelitis and the resulting severe disabilities.

- Crucially, the District Court found that the doctor at the public health center who administered the vaccine had been negligent. This negligence, the court held, stemmed from a breach of the duty to conduct a careful and thorough pre-vaccination medical examination. This failure in the pre-examination process, the court concluded, led directly to the oversight of X's unsuitable health condition (his contraindicated status) for receiving the vaccine at that particular time.

- Based on these findings, the District Court held the defendants (the State and local authorities) liable for damages under Article 1 of the State Compensation Act. However, the court also found that there had been a degree of contributory negligence (assessed at 20%) on the part of X's mother, for allegedly not fully reporting X's recent health condition to the vaccinating doctor. After factoring in this contributory negligence and also deducting the value of certain statutory benefits that X had already received under the provisions of the Vaccination Act for his injuries, the District Court awarded X and his family a total of approximately JPY 34 million in damages.

Sapporo High Court (On Appeal):

- The defendants appealed the District Court's decision to the Sapporo High Court. The High Court, while it did affirm the existence of a causal link between the vaccination and X's disabilities, ultimately overturned the District Court's finding of liability against the state.

- The High Court arrived at a different factual determination regarding X's health status on the actual day of the vaccination. It found that X's earlier pharyngitis had, in fact, healed by that day. Based on this finding, the High Court concluded that X was not a "contraindicated person" at the time of the shot and was medically fit to receive the vaccination.

- Consequently, the High Court reasoned that even if there had been some level of insufficiency in the pre-vaccination examination conducted by the doctor, this alleged insufficiency was not legally causative of X's adverse outcome because, in the High Court's view, X was suitable for vaccination anyway. As a result, the High Court dismissed the State Compensation Act claim.

- It is also noteworthy that during the proceedings at the High Court, X and his parents had introduced an alternative legal claim for "loss compensation" (sonshitsu hoshō). This alternative claim was grounded in constitutional principles, particularly those relating to the protection of property rights (Article 29, paragraph 3, by analogy), individual dignity, and the right to life. The argument was that even if the act of vaccination was deemed lawful (i.e., not negligent), the severe and disproportionate harm suffered by X as a result of a state-mandated or recommended public health measure constituted a "special sacrifice" for the public good that warranted direct compensation from the state, independent of any finding of fault. The High Court, however, dismissed this alternative loss compensation claim, deeming it procedurally inadmissible at that stage. It reasoned that such a claim for loss compensation constituted a different cause of action (specifically, a type of "substantive party suit" in administrative litigation) and could not be properly joined with the original state compensation claim (which is a civil damages claim) during the appeal proceedings.

Aggrieved by the High Court's complete dismissal of their claims, X and his parents appealed this adverse decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

III. The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: Presuming "Contraindicated Status"

In its historically significant judgment of April 19, 1991, the Supreme Court of Japan overturned the decision of the Sapporo High Court and remanded the case for further proceedings consistent with its new directives. The Supreme Court's reasoning introduced a critical evidentiary presumption that substantially altered the legal landscape for vaccination injury cases in Japan, making it somewhat easier for plaintiffs to establish a basis for state liability.

A. The Inherent Problem of Causation in Vaccination Injuries

The Supreme Court began by acknowledging the profound difficulties often faced in definitively proving the precise medical cause of severe adverse reactions that occur following vaccinations. It noted that, generally, such reactions could be attributed to one of two main underlying factors:

- The individual who received the vaccine (the vaccinee) was, at the time of the vaccination, a "contraindicated person" (kinki-sha). This means that the vaccinee had a pre-existing medical condition or was in a particular circumstance (e.g., acute illness, fever) that made the administration of that specific vaccine medically inadvisable for them due to an increased risk of adverse effects.

- Alternatively, the vaccinee possessed a rare, individual, and perhaps latent personal predisposition or susceptibility that made them unusually prone to developing severe adverse reactions to the vaccine, even if they did not exhibit any of the standard contraindications and appeared otherwise healthy.

B. The "High Probability" of Contraindication as the More Likely Cause

The Supreme Court then made a crucial observation based on general medical understanding and statistical probability. It reasoned as follows:

- The types of conditions typically listed by medical authorities and in vaccination guidelines as contraindications for vaccination (e.g., common acute illnesses like colds or pharyngitis accompanied by fever, certain known allergies, specific pre-existing chronic conditions, etc.) are generally conditions that ordinary people might commonly experience, or they are relatively common diseases or sensitivities found within the general population.

- In stark contrast, a truly rare and idiosyncratic personal predisposition that would cause an individual to suffer a severe adverse reaction to a standard vaccine is, by its very definition, far less common in the population.

- Drawing from this comparison, the Supreme Court concluded that "the possibility of a certain individual falling under the category of a contraindicated person is far greater than the possibility of having such a personal predisposition."

- Therefore, the Court advanced the pivotal inference that "when a severe adverse reaction occurs due to a vaccination, it can be considered that there is a high probability that the said adverse reaction occurred because the vaccinee was a contraindicated person."

C. The Establishment of a Rebuttable Legal Presumption

Based on this assessment of "high probability," the Supreme Court established a significant, rebuttable legal presumption to be applied in vaccination injury cases:

- "Therefore, when a severe adverse reaction occurs due to a vaccination, it is appropriate to presume that the vaccinee was a contraindicated person, UNLESS special circumstances are recognized [by the court]."

- The Supreme Court then went on to identify two main categories of "special circumstances" that, if proven by the defendant (typically the state or the administering authority), could serve to rebut this presumption:

- Proof that "the pre-vaccination examination necessary to identify contraindicated persons was fully performed [by the vaccinating doctor or medical staff], but no grounds for deeming the person contraindicated could be discovered." This effectively places a significant burden on the state (or the entity responsible for the vaccination) to demonstrate not just that some pre-examination was done, but that it was thorough, comprehensive, and adequate according to prevailing medical standards for identifying contraindications.

- Proof that "the vaccinee had the aforementioned [rare] personal predisposition [to such a reaction]." The PDF commentary accompanying this case sagely notes that proving the existence of such a rare and specific individual predisposition is often extremely difficult, if not impossible, in practice, making this a particularly challenging avenue for defendants to successfully pursue in rebuttal.

D. Identifying the Flaw in the High Court's Reasoning and Ordering Remand

Applying this newly established framework of presumption to X's case, the Supreme Court found the Sapporo High Court's previous reasoning to be legally flawed:

- The High Court had concluded that X was fit for vaccination and was not a contraindicated person, primarily basing this finding on its determination that X's earlier pharyngitis (throat inflammation) had healed by the day of the vaccination. However, the Supreme Court scrutinized the basis for this "healing" finding. It pointed out that the High Court's conclusion appeared to rest mainly on the reported course of X's fever (which had reportedly subsided a couple of days before the vaccination was administered) and on the mother's general observation of X's condition on the vaccination day (which was not supported by an actual temperature reading taken at the time of the pre-examination, or other objective medical evidence from that specific day). The Supreme Court deemed this evidence insufficient to definitively rule out the possibility that X might still have been in a contraindicated state at the critical moment. It noted that "pharyngitis" is merely a symptom name indicating inflammation of the pharynx; the subsidence of fever does not necessarily mean that the underlying cause of the illness was fully resolved, nor does it confirm that other potentially contraindicated conditions were absent.

- Most critically, the Supreme Court emphasized that the High Court had reached its conclusion that X was fit for vaccination "without [sufficiently] deliberating on whether the necessary pre-vaccination examination was fully performed." It also observed that the High Court had not made any positive finding that X actually possessed a rare personal predisposition that could explain the severe reaction.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court held that "the High Court's judgment, which immediately rejected the appellants' assertion regarding the negligence of the person who administered the vaccine, on the grounds that X was in a suitable condition for vaccination at the time of the said vaccination, without deliberating on points such as whether a thorough pre-vaccination examination was conducted [to identify contraindications], should be said to have the illegality of insufficient deliberation (shinri fujin)."

As a result of these findings, the Supreme Court quashed the judgment of the Sapporo High Court and remanded the case back to that court (破棄差戻し - hakisashimodoshi) for further proceedings. These further proceedings were to include a more thorough examination of whether the doctor who administered the smallpox vaccine to X had, in fact, conducted a sufficiently thorough pre-vaccination medical examination as required by medical standards to identify any potential contraindications that should have precluded X from receiving the vaccine at that time.

IV. Legal Context and Broader Implications

The Supreme Court's 1991 decision was delivered against a backdrop of significant legal and social challenges concerning vaccination-related injuries in Japan. Its ruling has had far-reaching implications.

The "Devil's Lottery" and the Inherent Challenges in Proving Negligence:

- The PDF commentary accompanying this case provides essential background on the complex context of vaccination injury litigation in Japan. It explains that while mass vaccination programs are undeniably crucial for preventing the spread of dangerous infectious diseases and protecting public health, they can, in a very small but tragic number of instances, lead to severe and sometimes fatal adverse reactions in certain individuals. This unfortunate phenomenon is sometimes referred to in Japan as the "devil's lottery" (akuma no kuji), a term that captures the seemingly random and unavoidable nature of these rare but devastating outcomes, where even with all due care in administration, a small fraction of vaccinees may suffer serious harm.

- A major obstacle for victims and their families seeking legal redress through traditional tort law principles (which also underpin Japan's State Compensation Act, based on concepts of fault or negligence) is the inherent difficulty in proving, with the level of certainty typically required in tort cases, a direct and clear causal link between a specific act of negligence on the part of the vaccinating doctor (such as an allegedly flawed pre-examination or an error in technique) and the subsequent development of a severe adverse reaction. This difficulty is often compounded by the fact that the precise medical mechanisms underlying many types of vaccine-induced injuries are not always fully understood by medical science, especially if the reaction is of a type that can, albeit rarely, occur even in individuals who appear to be healthy and not contraindicated.

Administrative Relief Measures versus Judicial Compensation:

- In recognition of these evidentiary challenges and also acknowledging the overriding societal importance of maintaining effective public vaccination programs, Japan had, over time, established various administrative relief measures for individuals who suffer harm from vaccinations. By the time X's case was litigated, the Vaccination Act itself included provisions for statutory benefits to be paid to those who suffered illness, disability, or death determined to be due to vaccinations administered under the Act. However, as the PDF commentary pertinent to this line of cases notes, at least during the period when this litigation arose, the monetary level of these statutory benefits was often significantly lower than the compensation amounts that were typically awarded by courts in successful medical malpractice lawsuits or other comparable tort cases. This considerable disparity in potential recovery was a major motivating factor for many vaccine injury victims and their families to still choose to pursue judicial remedies through the courts, seeking what they considered to be fuller and more adequate compensation for their profound losses.

Alternative Legal Theories Explored for Vaccine Injury Compensation:

- The significant hurdles in proving negligence under traditional tort law prompted legal scholars, plaintiffs' lawyers, and even some lower courts in Japan to explore and advocate for alternative legal theories that might provide a more accessible or certain basis for securing compensation for vaccine-related injuries. The PDF commentary provides a useful summary of several of these alternative approaches that were being discussed or advanced around that time:

- Damages/Tort Theory (with doctrinal modifications): This approach sought to keep the claim for compensation within the established framework of tort law (i.e., the State Compensation Act, which requires a finding of an illegal, negligent act by a public official). However, to make it easier for plaintiffs to succeed, proponents suggested various doctrinal modifications. These included arguing for an expanded or more flexible understanding of what constitutes "negligence" in the specific context of public vaccinations, advocating for the introduction of legal presumptions of negligence or causation (as the Supreme Court ultimately did, in part, in this 1991 judgment), or even arguing for the application of a stricter form of liability, such as "danger liability" (kiken sekinin), where the party that creates or manages a known risk (even if the activity, like vaccination, is socially useful and generally safe) bears a greater degree of responsibility for any harm that results from that risk materializing.

- Loss Compensation Theory (sonshitsu hoshō setsu): This theory offered a fundamentally different conceptual basis for compensation, moving away from the idea of fault or illegality. It viewed mandatory or strongly recommended public vaccination programs as lawful and socially necessary state actions that are undertaken for the collective benefit of protecting public health (e.g., by preventing widespread epidemics). However, if these inherently lawful and beneficial programs inevitably cause severe and unforeseeable harm to a small number of individuals, that harm can be characterized as a "special sacrifice" (tokubetsu no gisei) that has been imposed on those unfortunate individuals for the good of the entire community. Under this theory, such "special sacrifices" should be compensated by the state, not as damages for an unlawful or negligent act, but as "just compensation." This is often analogized to the principles underlying Article 29, paragraph 3 of the Constitution of Japan, which mandates just compensation when private property is taken for public use. Proponents argued that a similar principle should apply, by analogy or by direct constitutional interpretation, to severe and unavoidable personal injuries resulting from public health measures. It is noteworthy that the PDF commentary states that several District Court judgments in mass vaccination injury lawsuits that were decided prior to this 1991 Supreme Court ruling had, in fact, adopted this loss compensation theory as a basis for awarding redress. These lower courts often did so by either direct analogy to Article 29(3) or by finding that such compensation was an inherent implication of constitutional principles safeguarding life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

- Result Liability Theory (kekka sekinin setsu): This theory, presenting yet another distinct approach, focused on imposing liability purely based on the adverse result (i.e., the severe injury), particularly in unique contexts like compulsory or highly promoted public vaccination programs where the state actively encourages or mandates an action that, while generally safe, carries inherent, albeit statistically small, risks of serious harm.

- Public Law Danger Liability Theory (kōhō-jō no kiken sekinin setsu): This theory, somewhat related to but distinct from private law concepts of danger liability (strict liability for ultra-hazardous activities), posited that when the state, through its official actions such as organizing and promoting a national vaccination program, creates a "special zone of danger" for its citizens, it should bear a public law responsibility to provide compensation for the unintended harmful consequences that arise from that state-created danger. This would apply even if the act of vaccination itself is considered lawful and properly administered, if an unavoidable adverse outcome occurs.

The Supreme Court's Chosen Path: A Presumption within the Tort Law Framework:

- In its pivotal 1991 judgment in X's case, the Supreme Court chose to primarily operate within the established legal framework of the State Compensation Act, which, as mentioned, is fundamentally based on proving fault or negligence leading to an illegal act. However, the Court significantly recalibrated the dynamics of such litigation by introducing the powerful evidentiary presumption that a vaccinee who suffers a severe adverse reaction was likely a "contraindicated person" at the time of vaccination.

- This presumption effectively shifted a considerable part of the evidentiary burden. Instead of the plaintiff having to definitively prove both that they were medically contraindicated and that the vaccinating doctor negligently failed to identify this specific contraindication, the presumption meant that contraindicated status was assumed unless the state could rebut it. The state could do so by proving either that a thoroughly adequate pre-vaccination examination was indeed conducted and genuinely revealed no contraindications, or, alternatively, by proving that the injury was actually due to a rare personal predisposition of the vaccinee (the latter, as the PDF commentary points out, being an exceptionally difficult proposition to prove in most medical contexts).

- The PDF commentary further observes that, particularly within the context of the older mass vaccination systems prevalent in Japan at the time (where pre-vaccination examinations were often conducted very quickly and perhaps superficially due to the large numbers of people being processed), this presumption of contraindicated status would, in many historical cases, likely stand unrebutted. This, in turn, would pave the way for a finding of negligence if the pre-examination was not demonstrably thorough and in accordance with proper medical standards.

Synergy with the Earlier 1976 "Influenza Vaccination" Supreme Court Ruling:

- The PDF commentary also draws an important and insightful connection between this 1991 Supreme Court decision and an earlier influential Supreme Court judgment from 1976 (often referred to in legal literature as the Showa 51 judgment), which concerned an influenza vaccination case. That 1976 ruling had established another evidentiary presumption that was helpful to plaintiffs in vaccine injury cases: it held that if a doctor administers a vaccine to a person who was in fact medically contraindicated for that vaccine, and a severe adverse reaction subsequently ensues, it is to be presumed that the doctor should have foreseen that such an adverse outcome was a possibility. This presumption of foreseeability is a key element in establishing the legal concept of negligence.

- The commentary suggests that these two Supreme Court judgments (the 1991 ruling on presumed contraindicated status and the 1976 ruling on presumed foreseeability of harm if contraindicated) can work in tandem to assist plaintiffs. The 1991 ruling helps establish, by way of presumption, that the vaccinee was likely in a contraindicated state. The 1976 ruling then helps establish, again often by presumption, that the doctor was negligent in proceeding with the vaccination of such a person because the potential for harm was, in the eyes of the law, foreseeable. Indeed, the Sapporo High Court, upon rehearing X's case after it was remanded by the Supreme Court in 1991, reportedly utilized both of these presumptions to ultimately find the vaccinating doctor negligent and to affirm the state's liability for X's injuries.

Impact on Japan's National Vaccination Policy:

- This 1991 Supreme Court judgment, along with a subsequent and highly influential Tokyo High Court decision in a major mass vaccination (MMR) case in 1992 (which also found the state liable, in that instance focusing on systemic negligence by the then Ministry of Health and Welfare in not taking sufficient measures to prevent contraindicated individuals from being vaccinated under the program's design), are widely credited by legal and public health commentators with having a significant and transformative impact on Japan's national vaccination policy and practices. These judicial decisions, by holding the state accountable and by highlighting deficiencies in past practices, are seen as having contributed to a notable shift away from older, less individualized mass vaccination approaches. They spurred reforms aimed at placing a greater emphasis on conducting thorough pre-vaccination screenings, providing more comprehensive information to vaccinees (or their parents), and making more careful assessments of individual suitability for vaccination before administration.

V. Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's April 19, 1991, decision in the Otaru smallpox vaccination case represents a critical and compassionate development in the nation's legal response to the tragic issue of vaccine-related injuries. By establishing a rebuttable presumption that individuals who suffer severe adverse reactions following a public vaccination were likely "contraindicated persons" unless specific rebutting evidence is provided by the state, the Court significantly eased the often formidable burden of proof that had previously rested upon plaintiffs in seeking compensation under the State Compensation Act.

This nuanced ruling, particularly when understood in conjunction with earlier Supreme Court precedents concerning the foreseeability of harm in medical negligence contexts, provided a clearer and more accessible pathway for victims of vaccine injuries to obtain meaningful redress within the existing tort law framework. It achieved this without the Court needing to explicitly adopt or endorse more radical, no-fault theories of loss compensation for these specific types of cases, though the PDF commentary suggests such theories might still hold relevance for truly unavoidable adverse reactions.

The judgment is recognized not only for its profound impact on the outcomes of individual vaccine injury cases but also for its broader, systemic influence on public health policy in Japan. It is widely seen as having contributed to important reforms in the country's vaccination practices, fostering an environment that places a greater emphasis on individualized risk assessment, thorough pre-vaccination screening, and overall vaccine safety. In doing so, the decision underscored the state's profound responsibility when implementing public health measures that, while essential and beneficial for society at large, inevitably carry inherent, albeit small, risks for a minority of individuals.