Vacate First, Deposit Later? Japanese Supreme Court on Security Deposits and Simultaneous Performance

Date of Judgment: September 2, 1974

Case Name: Claim for Surrender of Leased Premises

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

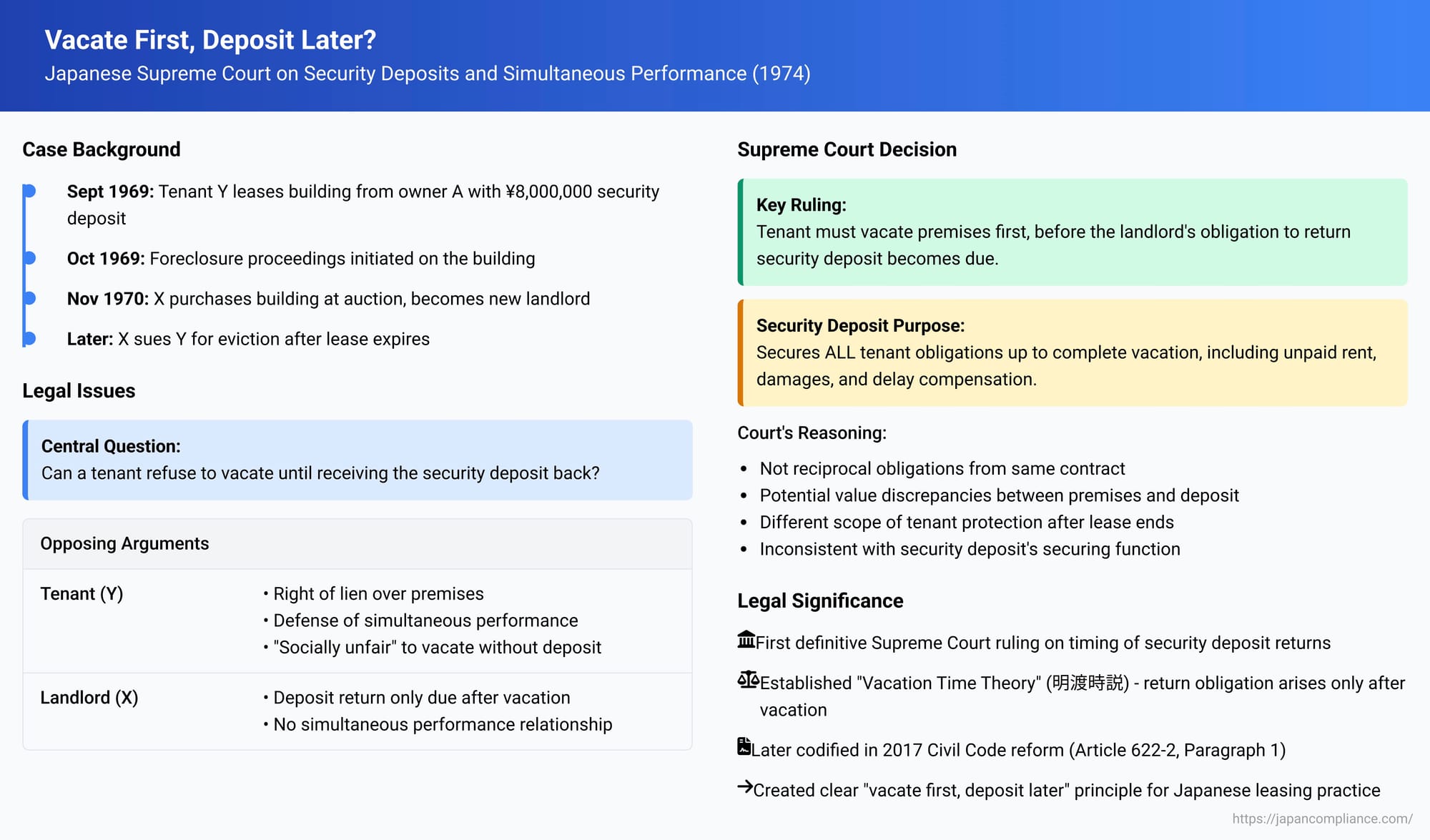

In Japan, as in many countries, tenants typically provide a security deposit (敷金 - shikikin) to their landlord upon entering a lease agreement. This sum serves as security for the tenant's obligations. A common point of contention at the end of a lease is the timing of this deposit's return. Does the tenant have the right to withhold possession of the property until the security deposit is refunded, or must they vacate the premises first, with the deposit return following later? A landmark Japanese Supreme Court decision on September 2, 1974, addressed this very practical question, clarifying the relationship between a tenant's duty to vacate and a landlord's duty to return a security deposit.

A Lease Ends, A Foreclosure, A Dispute: The Case Background

The case arose from a somewhat complex set of circumstances:

- The Original Lease and Security Deposit: Y (the tenant) leased portions of a four-story building from the original owner, A. The lease term was for two years, commencing September 1, 1969, with a monthly rent of ¥168,000. Upon signing, Y paid A a substantial security deposit of ¥8,000,000.

- Mortgage and Foreclosure: Unbeknownst to Y at the time of leasing, the building was already subject to a mortgage (a revolving mortgage, or neteitōken) established in 1968. In October 1969, shortly after Y's lease began, foreclosure proceedings were initiated against the property.

- New Landlord via Auction: In November 1970, X purchased the building at a foreclosure auction, thereby acquiring ownership and becoming Y's new landlord. X completed the ownership transfer registration in the same month.

- Eviction Lawsuit and Defenses: X subsequently sued Y for eviction. In the lower courts:

- The first instance court initially dismissed X's claim, finding Y's lease to be a "short-term lease" that could be asserted against X (a legal concept offering some protection to tenants against mortgagees, though since abolished).

- X appealed. In the High Court, Y no longer argued a right to occupy beyond the original two-year lease term (which had expired). Instead, Y asserted a right to purchase fixtures and, more importantly for this Supreme Court case, claimed a right of lien (retention) over the premises and a defense of simultaneous performance. Y argued they should not have to vacate until their claim for the return of the ¥8,000,000 security deposit was met by X.

- The High Court ruled in favor of X. It held that the security deposit return obligation only arises after the tenant vacates the leased property. Therefore, Y could not claim a lien or assert that the vacation and deposit return were simultaneous obligations.

- Appeal to the Supreme Court: Y appealed to the Supreme Court, contending that it was socially unfair for a landlord to demand vacation without returning the security deposit and that a right of lien based on the deposit return claim should be recognized. Y also argued a prevailing custom of returning deposits upon vacation.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: No Simultaneous Performance

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, affirming the High Court's decision that the tenant must vacate first. The Court provided a detailed explanation for why the tenant's obligation to vacate and the landlord's obligation to return the security deposit are not in a relationship of simultaneous performance.

Defining the Security Deposit's Role

The Court began by clarifying the fundamental nature and purpose of a security deposit in a lease:

- It secures all of the tenant's monetary obligations to the landlord that may arise throughout the lease and up until the tenant completely vacates the premises after the lease terminates. This includes unpaid rent, compensation for damages to the property, and damages for any delay in vacating.

- The landlord's obligation is to return the net remaining balance of the security deposit. This balance is determined only after the tenant has vacated the premises and the landlord has deducted all outstanding secured claims. This point was supported by an earlier Supreme Court precedent (February 2, 1973).

Why Not Simultaneous Performance?

Based on this understanding of the security deposit, the Court offered several reasons for rejecting the idea of simultaneous performance:

- Not Reciprocal Obligations from the Same Core Contract: While a security deposit agreement is ancillary to (accompanies) the lease agreement, it is not the lease agreement itself. The tenant's duty to vacate arises from the lease contract, while the landlord's duty to return the deposit arises from the separate security deposit agreement. Therefore, these are not "reciprocal" (対価的 - taikateki) obligations stemming from a single bilateral contract, which is the usual basis for the defense of simultaneous performance (governed by Article 533 of the Civil Code).

- Potential for Unfairness due to Value Discrepancies: There can be a significant difference in the economic value of the obligation to vacate a property versus the amount of the security deposit to be returned (especially after deductions). Forcing strict simultaneity might not always align with principles of fairness.

- Scope of Tenant Protection: The primary need for tenant protection in a lease relationship concerns the tenant's right to use and occupy the property during the lease term. The issue of security deposit return arises after the lease has ended and concerns a financial settlement. The Court felt that emphasizing tenant protection to the extent of granting simultaneous performance for deposit return was not as compelling as protecting their right of use during the lease.

- Inconsistency with the Security Deposit's Securing Function: The very purpose of a security deposit is to secure all tenant obligations up to the point of actual vacation. If the landlord had to return the deposit at the exact moment of receiving the keys, the deposit could not effectively cover damages discovered only upon inspection of the vacated premises or compensation for the tenant holding over. Affirming simultaneous performance would undermine this essential securing function.

Conclusion on Timing: Vacate First

The Supreme Court concluded that, absent a specific contractual agreement stating otherwise, a landlord is only obliged to return the net balance of the security deposit after the tenant has vacated the premises. This means the tenant's obligation to vacate is a prior obligation (先履行 - saki rikō). This principle applies regardless of how the lease terminated (e.g., expiration of term, cancellation by either party).

No Right of Lien

Since the tenant's duty to vacate precedes the landlord's matured obligation to return the net security deposit (which only becomes fixed after vacation and deduction of claims), the tenant cannot assert a right of lien (or right of retention) over the leased premises based on their claim for the security deposit's return. The claim for the deposit return is not yet fully determined and unconditional before vacation.

Deeper Dive: The Legal Mechanics and Implications

This 1974 Supreme Court ruling was a landmark, being the first to definitively clarify that there is no simultaneous performance relationship between vacating a leased property and the return of a security deposit.

Academic Debate on Security Deposit Nature (Pre-2017 Civil Code Reform)

Before the Civil Code reforms in 2017, the precise legal nature of security deposits and the timing of the landlord's return obligation were extensively debated by scholars:

- "Suspensive Condition" Theory: The prevailing view was that a security deposit involved a transfer of money to the landlord, with the landlord's obligation to return it being subject to a "suspensive condition" – namely, that no outstanding tenant debts exist at the time of lease termination or vacation.

- Timing of Return Obligation:

- "End of Lease Theory" (終了時説 - shūryōji setsu): Some argued the return obligation (or at least the claim for it) arises when the lease contract itself terminates.

- "Vacation Time Theory" (明渡時説 - akewataji setsu): Others, more aligned with the practical function of the deposit, argued the obligation to return the net amount arises only when the tenant actually vacates the premises. The 1974 Supreme Court judgment, building upon a 1973 precedent, firmly endorsed this "Vacation Time Theory."

- Scope of Secured Debts: The "Vacation Time Theory" naturally allows the security deposit to cover all tenant obligations that accrue up to the point of complete vacation.

The Simultaneous Performance Debate

Even among those who accepted the "Vacation Time Theory," there was debate about whether simultaneous performance could still apply. Some argued that even if the exact amount of the deposit to be returned is finalized only upon vacation, the principle of fairness underlying simultaneous performance (Civil Code Art. 533) could be applied by analogy. The 1974 Supreme Court explicitly rejected this by not just relying on the timing mechanics but also by engaging in a substantive balancing of interests, considering overall fairness, the appropriate scope of tenant protection post-termination, and the functional nature of the security deposit.

The 2017 Civil Code Reform

The Civil Code of Japan was significantly revised in 2017, with new provisions coming into effect. Article 622-2, Paragraph 1 now formally defines a security deposit and codifies the principles established by prior case law, including the 1974 Supreme Court decision:

- It defines a security deposit as money paid by the tenant to the landlord, regardless of its name, to secure the tenant's monetary obligations arising from the lease.

- Crucially, it states that the landlord must return the security deposit (after deducting any secured obligations) "when the lease has terminated and the leased property has been returned to the landlord."

This statutory language clearly adopts the "Vacation Time Theory" and makes the tenant's return of the property a prerequisite for the landlord's obligation to return the net deposit. While the Civil Code doesn't explicitly use the term "prior obligation" or directly negate "simultaneous performance" for security deposits in this article, the textual structure strongly supports the interpretation that vacation must occur first. Legal commentary on the new provision generally aligns with this view. The practical challenge then shifts from arguing about simultaneity to ensuring mechanisms for the timely and fair return of the deposit after vacation.

Conclusion

The 1974 Supreme Court decision established a clear and practical rule: tenants in Japan are generally required to vacate leased premises before the landlord's obligation to return the net balance of the security deposit becomes due. This "vacate first, deposit later" principle prioritizes the security function of the deposit, allowing landlords to assess and cover any outstanding tenant liabilities up to the very end of the occupancy. This long-standing judicial precedent has now been largely enshrined in the revised Civil Code, providing a more explicit statutory basis for this widely understood aspect of Japanese leasing practice.