Urban Planning, Discretion, and Judicial Review: Lessons from Japan's Odakyu Line Case

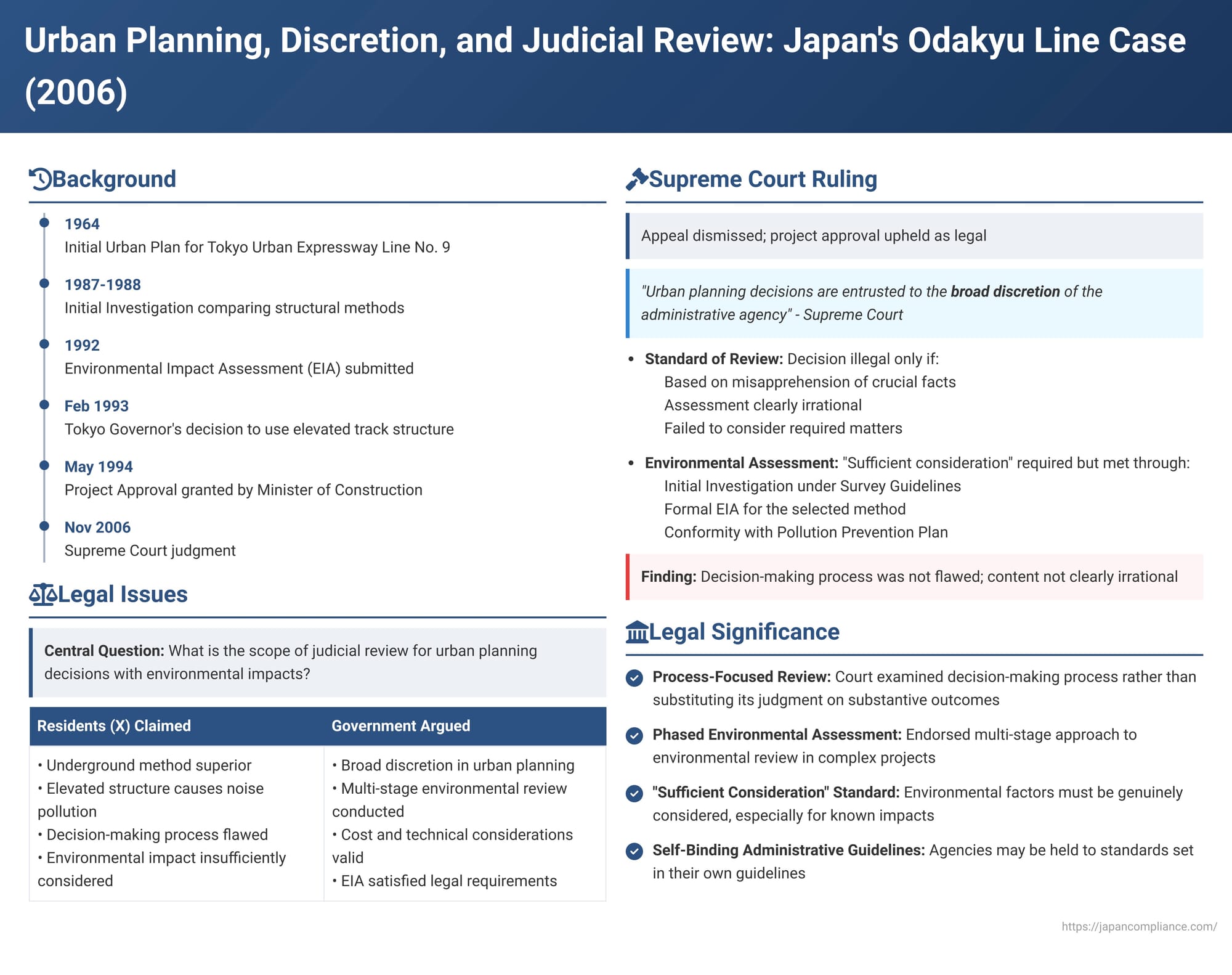

Date of Judgment: November 2, 2006, First Petty Bench, Supreme Court of Japan

Major infrastructure projects invariably involve a complex interplay of public interest, private rights, technical considerations, and policy choices. Urban planning decisions, which lie at the heart of such projects, are often vested with broad administrative discretion. A landmark decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on November 2, 2006, concerning the Odakyu Line continuous grade separation project in Tokyo, provides significant insights into the scope of this discretion and the standards for its judicial review, particularly concerning environmental considerations and the decision-making process.

The Factual Background: A Railway Project and Resident Concerns

The case involved a challenge by a group of residents (hereinafter X) living along the Odakyu Odawara Line in Tokyo against the approval of a major railway infrastructure project.

- Historical Context and Initial Plans: The roots of the dispute trace back to an urban plan for Tokyo Urban Expressway Line No. 9 (the Line 9 Urban Plan), initially decided in 1964 by the Minister of Construction under the Old Urban Planning Act. This plan underwent several modifications over the years.

- The 1993 Urban Plan Modification Decision: In February 1993, the Governor of Tokyo (represented as G in this summary, as the participating appellee), acting under the Urban Planning Act, made a crucial modification to the Line 9 Urban Plan (hereinafter, the 1993 Decision). This decision pertained to a specific segment of the Odakyu Odawara Line, from the vicinity of Kitami Station to Umegaoka Station (the Project Section). The 1993 Decision specified that this section would be upgraded through continuous grade separation, primarily using an elevated track structure (the Elevated Method), with an exception for a cut-and-cover (excavated) section near Seijogakuen-mae Station. The objectives were to improve railway convenience, alleviate train congestion, eliminate traffic delays at level crossings, and facilitate integrated urban development, in conjunction with the Odakyu Line's track-doubling (from two to four tracks) project.

- The Path to the 1993 Decision:

- The Initial Investigation (Pre-1993): Between fiscal years 1987 and 1988, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government conducted a survey (the Initial Investigation) based on a national directive called the Continuous Grade Separation Project Survey Guideline (the Survey Guideline). This was to assess the need and urgency for quadrupling tracks and implementing continuous grade separation for a part of the Odakyu Line, including the Project Section. The Survey Guideline stipulated that comparative evaluations of several basic design proposals should consider factors like economic efficiency, ease of construction, coordination with related projects, project effectiveness, and environmental impact. The Initial Investigation concluded that for a significant portion of the Project Section, the Elevated Method was appropriate, being superior in terms of construction period and cost compared to a partial underground option, and that while environmentally inferior, its impact could be minimized.

- G's Comparison of Alternatives: Based on the Initial Investigation, G then compared three main structural methods for the Project Section: (1) the Elevated Method (as ultimately chosen), (2) a combination of elevated and underground sections, and (3) a fully underground method (the Underground Method). This comparison focused on three sets of conditions: planning conditions (e.g., elimination of level crossings, station relocation), topographical conditions, and project-related conditions (e.g., project costs). G concluded that the Elevated Method was superior across all three conditions. For instance, the Underground Method was seen as problematic for eliminating certain level crossings near an adjacent section (the Shimokitazawa section) planned as surface-level at the time, and would require deeper construction to pass under rivers. Project costs for the Elevated Method were estimated at approximately 190 billion yen, significantly less than the 300-360 billion yen estimated for underground options. G determined that even considering environmental impact and spatial use of railway land, the Elevated Method was not problematic.

- Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA): Subsequently, the railway operator (Company A) and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government conducted an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for the Project Section, specifically for the proposed Elevated Method, pursuant to the Tokyo Metropolitan Environmental Impact Assessment Ordinance (the EIA Ordinance). An EIA report (the EIA Report) was submitted to G in December 1992. This report predicted future railway noise levels (e.g., at 1.2m height, generally similar to or lower than existing levels, though some areas slightly higher; at 10-30m height at a point 1.5m from the viaduct, predicted at 88dB(A) or more). It also outlined noise mitigation measures (e.g., heavier structures, ballast mats, heavier rails, sound-absorbing walls, consideration of interference-type sound-damping devices) expected to considerably reduce actual noise levels. The EIA was conducted based on established scientific methods and guidelines.

- Pollution Disputes Committee Finding: Meanwhile, some residents (X) had filed a claim with Japan's Environmental Disputes Coordination Commission regarding railway noise from the Odakyu Line. In July 1998 (though the application was in 1992, before the 1993 Decision), the Commission ruled that noise pollution experienced by some residents prior to the 1993 Decision had exceeded tolerable limits, holding Company A liable for damages.

- Finalizing the 1993 Decision: G, after considering the Initial Investigation and the EIA results, judged that the Elevated Method posed no particular problems regarding environmental impact and formally made the 1993 Decision. The decision was also found to be compatible with the existing Tokyo Regional Pollution Prevention Plan (the Pollution Prevention Plan) established under the Basic Law for Pollution Control.

- The Project Approval (1994): Based on the 1993 Decision, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government applied to the Minister of Construction. In May 1994, the Minister (whose authority was later succeeded by Y, the Director-General of the Kanto Regional Development Bureau) granted project approval (the Project Approval) for the railway grade separation project and associated access road projects under Article 59(2) of the Urban Planning Act.

- The Lawsuit: X filed a lawsuit against Y seeking the revocation of the Project Approval. Their central argument was that the underlying 1993 Decision was illegal because it adopted the Elevated Method – which they claimed was inferior in terms of cost and environmental impact (particularly noise) and would cause significant harm to residents – while unreasonably rejecting a superior alternative, the Underground Method.

The case progressed through lower courts, with the first instance court ruling for X and the second instance court ruling against X (denying standing to some and dismissing claims for others). After a separate Supreme Court Grand Bench ruling on the issue of plaintiff standing for X, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court delivered this judgment on the merits of the Project Approval itself.

The Legal Framework: Urban Planning and Project Approval in Japan

The Urban Planning Act forms the bedrock of city planning in Japan. It outlines procedures for establishing urban plans, including those for urban facilities like railways. These plans aim to promote healthy and cultured urban life and functional urban activities.

- Urban Planning Decisions: These decisions, made by entities like prefectural governors (such as G), define the type, name, location, and scope of urban facilities. They must conform to broader objectives like ensuring a good urban environment and, if a pollution prevention plan exists, must be compatible with it.

- Project Approval: Once an urban plan for a facility is decided, specific projects to construct these facilities require "project approval" from the Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (or delegated authorities like Y) under Article 59 of the Act. This approval is a prerequisite for commencing the urban development project and, importantly, confers powers such as land expropriation if necessary. One of the criteria for project approval is that the project must conform to the established urban plan (Article 61). Thus, the legality of the project approval hinges on the legality of the underlying urban plan decision.

- Environmental Considerations: The Act mandates consideration of the environment. The EIA Ordinance in Tokyo further operationalizes this by requiring EIA for certain projects, and the planning authority must give "due consideration" to the EIA report.

The Supreme Court's Decision of November 2, 2006

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, upholding the High Court's decision that had rejected their claims. The Court's reasoning carefully delineated the scope of administrative discretion in urban planning and the standards for judicial review.

1. Broad Discretion in Urban Planning

The Court first established the significant degree of discretion enjoyed by administrative authorities in making urban planning decisions:

- Nature of Urban Planning: The Urban Planning Act requires authorities to determine the scale, location, and other aspects of urban facilities by comprehensively considering various circumstances (land use, traffic, present and future outlooks) from both policy and technical perspectives, aiming for smooth urban activities and a good urban environment.

- Indispensable Judgment: Such determinations are inherently complex and necessitate judgments that blend policy goals with technical feasibility.

- Entrustment to Broad Discretion: Consequently, these judgments are entrusted to the "broad discretion" of the administrative agency responsible for the decision.

- Standard of Judicial Review: When courts review the legality of an urban planning decision (or its modification), they must presume it was made within this discretionary power. A decision can only be found illegal if it oversteps or abuses this discretion. This occurs if:

- The decision is based on a misapprehension of crucial facts, thereby lacking a proper factual foundation.

- The assessment of facts is clearly irrational.

- The decision-making process failed to consider matters that legally should have been considered, or considered irrelevant matters, rendering the decision's content remarkably lacking in validity when viewed against societal norms.

This standard, typically applied to administrative dispositions, was thus explicitly extended to the review of administrative plans like urban planning decisions.

2. Environmental Considerations as a Key Requirement

The Court then focused on the environmental duties incumbent upon G when making the 1993 Decision:

- Duty to Prevent Harm: The 1993 Decision, being a premise for the Project Approval, required measures to prevent significant harm to the health or living environment of residents in surrounding areas from noise, vibration, and other impacts of the grade separation project.

- Conformity and Due Consideration: This included ensuring conformity with the Tokyo Regional Pollution Prevention Plan and giving "sufficient consideration" (十分配慮 - jūbun hairyo) to the contents of the EIA Report to achieve appropriate environmental conservation. The EIA Ordinance specifically required G to request planning authorities to give such sufficient consideration to EIA reports.

- Heightened Duty Regarding Noise: The Court specifically noted that because the Environmental Disputes Coordination Commission had (in a later ruling concerning the pre-1993 period) found that noise pollution for some Odakyu line residents had already exceeded tolerable limits, "sufficient consideration" of railway noise was particularly mandated when G was determining the structure for the Project Section in the 1993 Decision.

3. Assessment of the Decision-Making Process in This Case

Applying these principles, the Court found no illegality in G's 1993 Decision to adopt the Elevated Method:

- Multi-Stage Consideration of Environment:

- G's initial comparison of three alternative methods (Elevated, Combined, Underground) focused on planning, topographical, and project-related conditions. At this specific stage of direct comparison, environmental impacts were not the explicit comparative elements that led to the Elevated Method being deemed superior.

- However, the Court emphasized that this comparison itself was undertaken based on the findings of the earlier Initial Investigation. That Initial Investigation, conducted under the Survey Guideline, had incorporated environmental aspects (along with construction period/cost) and had concluded that the Elevated Method was appropriate.

- Furthermore, after this initial selection process and before the final 1993 Decision, a formal EIA was conducted specifically for the chosen Elevated Method, as required by the EIA Ordinance. G made the 1993 Decision after considering the results of this EIA Report.

- Conclusion on Process: Given this multi-stage consideration, the Court concluded that it "cannot be said that the 1993 Decision failed to consider matters that should have been considered in its decision-making process". The Court found that the 1993 Decision, taking into account the EIA Report and aiming to prevent significant harm from noise and other impacts, gave appropriate consideration to environmental preservation, conformed with the Pollution Prevention Plan, and did not lack "sufficient consideration" for railway noise. The decision-making process was not deemed flawed, nor was its content found to be clearly irrational.

- Other Considerations (Cost, Technical Feasibility): The Court also found G's cost calculation methods (which excluded past land acquisition costs and benefits to the railway operator) to be reasonable for predicting future expenditure. G’s decision not to exhaustively analyze an all-underground option using a specific tunneling method (shield method) for the entire section was also deemed not unreasonable, given the technical limitations at the time for constructing wide station areas using that method. Even though the plan for the adjacent Shimokitazawa section was later proposed to be underground, G's 1993 judgment based on the then-existing surface plan for that section was not considered irrational.

Therefore, since the 1993 Decision (the premise) was not illegal, the subsequent Project Approval by Y based on that decision was also not illegal.

Key Takeaways and Analysis

This Supreme Court judgment carries significant implications for understanding administrative discretion in urban planning and the nature of judicial oversight:

1. Planning Discretion Affirmed, Process Scrutinized:

The ruling strongly reaffirms the broad "planning discretion" granted to administrative bodies in complex urban development decisions, acknowledging the need for policy and technical expertise. However, this discretion is not a carte blanche. The Court's detailed examination of the decision-making process – particularly the stages of consideration for environmental impacts – demonstrates that while the substantive outcome might be hard to challenge, the procedural integrity of how that outcome was reached is subject to careful judicial review.

2. "Sufficient Consideration" as a Potentially Demanding Standard:

The Court's repeated emphasis on the need for "sufficient consideration" of environmental factors, especially railway noise in light of pre-existing issues, is noteworthy. While the judgment ultimately found this standard was met, the phrasing suggests a potentially more intensive review than merely checking if a factor was "mentioned" or "formally considered." It implies a qualitative aspect to the consideration, although some scholars have questioned whether the Court delved deeply enough into the substance of the environmental review or was satisfied by the formal completion of processes. The requirement for "sufficient consideration" can be linked to the statutory mandate for urban plans to conform with pollution prevention plans.

3. Acceptance of Phased Environmental Review:

The judgment appears to endorse a multi-stage approach to environmental assessment in complex projects. An initial survey comparing broad alternatives (which includes environmental aspects among others) can narrow down options, followed by a more detailed EIA on the preferred option before a final decision is made. This pragmatic approach acknowledges the evolving nature of project planning.

4. The Implicit Weight of Internal Guidelines (Self-Binding Effect):

The Court noted that G's initial comparison of methods was based on the Initial Investigation, which itself was conducted under the Survey Guideline that required consideration of environmental impacts. By factoring this into the legality of the overall process, the Court lends implicit weight to such internal administrative guidelines. This suggests that agencies may be held to the standards they set for themselves, contributing to the rationalization and accountability of the entire planning process and blurring the distinction between judicial control of planning discretion and that of ordinary administrative acts.

5. Abstract Harm in Planning vs. Procedural Soundness:

Urban planning decisions often occur early in a project's lifecycle, and the direct infringement on individual rights (like health or environmental interests) might appear more abstract or potential compared to later stages like land expropriation. Plans can also be modified. This context might sometimes lead to more deferential judicial review when balancing these interests against public benefits. However, this case shows that even if direct harm is yet to materialize fully, the soundness of the decision-making procedure, including the thoroughness of environmental consideration, is a critical benchmark for legality.

6. Nexus Between Plaintiff Standing and Merits Review:

The environmental interests that X invoked – harm to health and living environment from noise – were not only central to their arguments on the merits but were also the kind of "individual interests" that could (and in a related Grand Bench decision, did) establish their standing to sue. This case illustrates the close connection between the legal interests considered for granting standing and the substantive considerations weighed in reviewing the exercise of administrative discretion. The factors an agency is required to "sufficiently consider" often mirror the interests the law deems worthy of direct protection through litigation.

7. Defining the Scope and Timing of Review:

The Court upheld the lower court's focus on the 1993 Decision as the relevant administrative act for judicial scrutiny, with the legality judged as of the time that decision was made. This is important in long-term projects with multiple planning stages.

Relevance and Enduring Principles

The Odakyu Line case continues to be a significant reference point in Japanese administrative law. While specific environmental regulations and planning laws evolve, the core principles regarding the scope of planning discretion, the judiciary's role in reviewing the process of such discretionary decisions, the importance of "sufficient consideration" for legally mandated factors (especially environmental protection), and the self-binding nature of administrative guidelines remain highly relevant. It highlights the judiciary's effort to ensure that even broad discretionary powers are exercised within a framework of rationality, procedural fairness, and due regard for protected interests.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2006 judgment in the Odakyu Line continuous grade separation project case underscores a critical balance in administrative law. It respects the necessity of broad discretion for administrative agencies in complex urban planning, recognizing the multifaceted policy and technical judgments involved. Simultaneously, it asserts a vital judicial role in scrutinizing the decision-making process to ensure that such discretion is not abused, particularly by failing to give sufficient and appropriate consideration to statutorily mandated concerns like environmental protection. The ruling emphasizes that a sound process, adhering to legal requirements and internal standards, is fundamental to the legitimacy of far-reaching administrative decisions.