Until Death Do Us Join? A 1970 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Marriage Registration After Loss of Consciousness

Date of Judgment: April 21, 1970

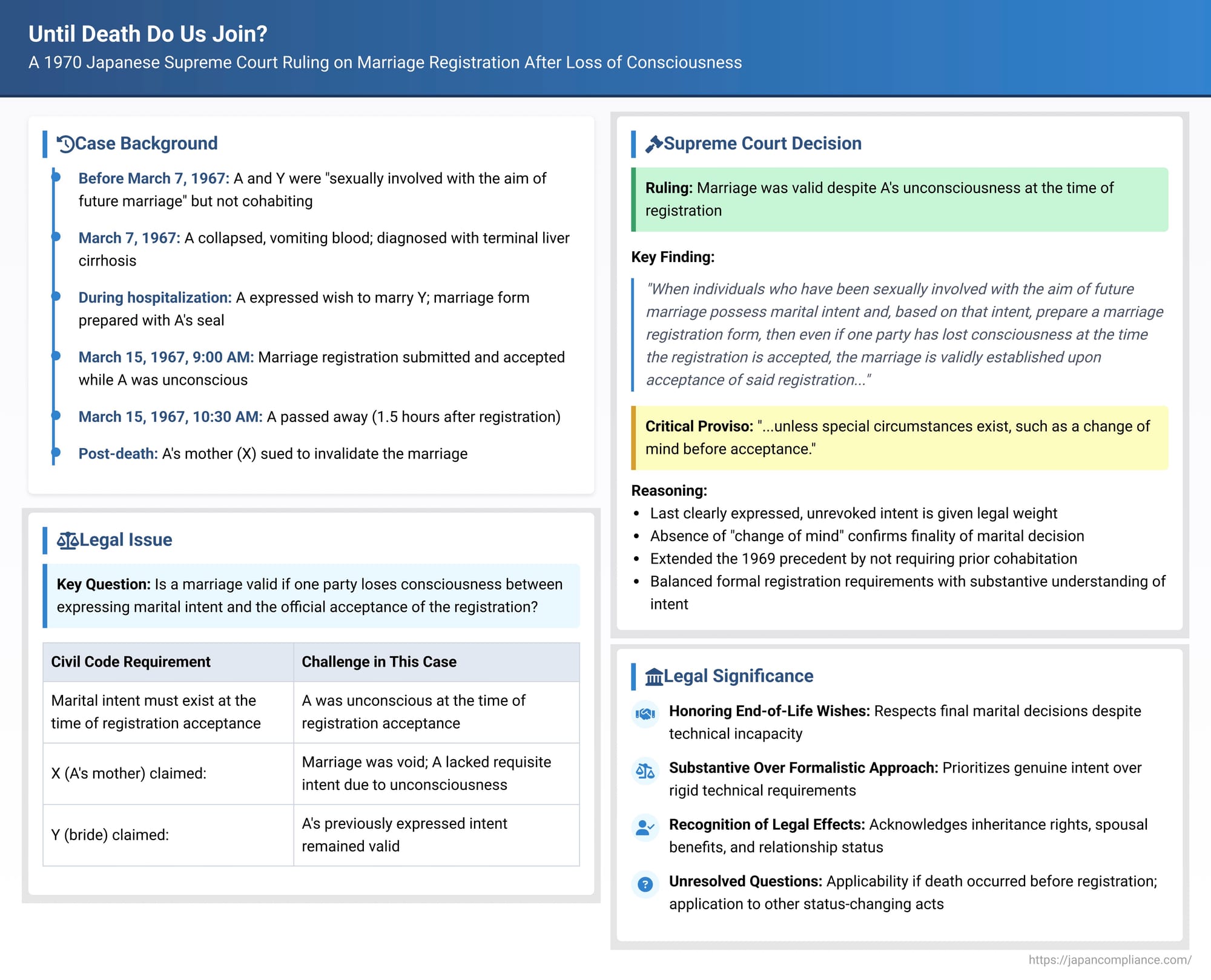

The formalization of marriage, especially when one party is near death, presents unique and poignant legal challenges. These "deathbed marriages" (rinjūkon in Japanese) often arise from a desire to legitimize a relationship, secure inheritance rights, or provide for a surviving partner. A critical question emerges: if one individual expresses a clear intent to marry and a marriage registration form is prepared, but they then lose consciousness before the registration is officially accepted by the authorities, is the marriage valid? This issue touches upon the fundamental requirement in Japanese law that marital intent must exist at the time of registration. The Supreme Court of Japan provided a significant ruling on this matter on April 21, 1970 (Showa 45 (O) No. 104).

The Facts: A Race Against Time and a Mother's Challenge

The case involved a man, A, and a woman, Y, who had been in a relationship described by the Court as "sexually involved with the aim of future marriage," though they were not cohabiting. Their plans took a tragic turn on March 7, 1967, when A suddenly collapsed, vomiting blood. After returning home, he experienced two more episodes of massive hematemesis and fell unconscious.

A was hospitalized, and emergency surgery revealed that the bleeding was due to ruptured esophageal varices caused by liver cirrhosis. His condition was deemed untreatable; the surgery was halted, and the incision was closed, with medical staff essentially observing his final course. While in the hospital, A clearly expressed his wish to formally marry Y. He conveyed this desire to both Y and his brother, B. At A's request, B filled out the official marriage registration form in A's name and affixed A's personal seal to it.

On the morning of March 15, 1967, at 9:00 AM, as soon as the local ward office opened, the marriage registration form for A and Y was submitted and accepted. However, on that same morning, A suffered another major hemorrhage. He passed away at 10:30 AM, just one and a half hours after the marriage registration was officially completed. It is understood that A was unconscious, or at the very least in a moribund state, at the precise time the registration was accepted.

Following A's death, his mother, X, initiated legal proceedings to have the marriage between A and Y declared null and void. X contended that the marriage registration was not based on A's genuine will but was a sham orchestrated by Y and A's brother, B, with the ulterior motive of fraudulently obtaining pension and mutual aid society benefits to which a surviving spouse might be entitled. The appellate court, however, had found the marriage to be valid. X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, arguing that A was on the brink of death at 9:00 AM on March 15th and therefore lacked the requisite marital intent, rendering the marriage void.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding the Deathbed Marriage

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby affirming the validity of the marriage between A and Y. The Court's reasoning built upon and clarified principles from a similar, recent precedent.

The Core Principle Reiterated and Extended:

The Court declared: "When individuals who have been sexually involved with the aim of future marriage possess marital intent and, based on that intent, prepare a marriage registration form, then even if one party has lost consciousness at the time the registration is accepted, the marriage is validly established upon acceptance of said registration, unless special circumstances exist, such as a change of mind before acceptance."

This principle directly referenced an earlier Supreme Court First Petty Bench ruling from April 3, 1969 (Showa 44.4.3, Minshu Vol. 23, No. 4, p. 1), which had also upheld a marriage registered while one party was unconscious. The Court found that under the various circumstances established by the appellate court concerning the preparation and submission of A and Y's marriage registration, the appellate court's judgment upholding its validity was appropriate.

Evolution from the 1969 Precedent: No Cohabitation Required

The 1970 Supreme Court decision is particularly significant because it extended the principle established in the 1969 precedent. The 1969 case involved a couple who were already in a de facto marital relationship (内縁関係 - nai'en kankei), meaning they were cohabiting as husband and wife without formal registration. Upholding their deathbed marriage could be seen, in part, as a way of giving legal recognition and protection to that established relationship.

The 1970 case, however, involved A and Y, who, while "sexually involved with the aim of future marriage," were not cohabiting. By finding their marriage valid under similar circumstances of unconsciousness at registration, the Supreme Court indicated that a pre-existing state of cohabitation was not an absolute prerequisite for applying this principle. This marked a notable development in the law concerning deathbed marriages.

Reconciling with the "Intent at Time of Registration" Rule

A fundamental tenet of Japanese marriage law (Civil Code Articles 739 and 742(1)) is that for a marriage to be valid, the parties must have the intent to marry, and this intent must, traditionally, exist at the moment the marriage registration is officially accepted by the authorities. How, then, can a marriage be valid if one party is unconscious, and arguably incapable of possessing any active intent, at that critical moment?

The Supreme Court's approach does not suggest that an unconscious person actively possesses marital intent. Instead, it gives decisive legal weight to the last clearly expressed, unrevoked intent that the person manifested while they were conscious and capable of forming such an intent.

The "No Change of Mind" Proviso is Key:

The crucial qualifying phrase in the Court's reasoning is "unless special circumstances exist, such as a change of mind before acceptance". This proviso is vital. It implies that if A, after consenting to the marriage and the preparation of the registration form but before its submission and while he was still conscious, had clearly indicated that he no longer wished to marry Y, the outcome would likely have been different; the marriage would probably have been deemed void. The absence of such a revocation or "change of mind" allows his prior, consciously formed intent to marry Y to be given legal effect, even though he subsequently lost consciousness.

Legal commentary suggests that this emphasis on the absence of a "change of mind" serves to confirm the finality of the individual's last expressed wish regarding their marital status. It's not about presuming that marital intent magically continues during unconsciousness, but rather about respecting the last authentic decision made by the individual when they were capable of making it. This approach seeks to avoid invalidating a marriage solely due to the subsequent, involuntary loss of consciousness, provided the initial intent was clear and remained unaltered.

Some legal scholars have debated whether intent at the time of creating the marriage form should suffice, with the later registration being merely a condition for effect. The Supreme Court's approach, with its "no change of mind" condition, differs slightly by still allowing for the possibility that a conscious revocation of intent after creating the form but before registration could prevent the marriage from becoming effective. This prioritizes the individual's most recent, conscious decision.

Why Uphold Such Marriages? The Multifaceted Nature of Marriage

One might question the purpose of formalizing a marriage when one party is on their deathbed and there is no prospect of a shared marital life. However, marriage in law entails more than just cohabitation and daily companionship. It creates a legal status with significant consequences, including:

- Inheritance rights for the surviving spouse.

- Entitlement to spousal benefits, such as pensions or mutual aid payments.

- Formal legal recognition of a relationship.

- Potential legitimation of children.

The law, through decisions like this one, acknowledges that individuals may have legitimate reasons to want to secure these legal effects for their partners, even at the very end of life. The courts, by upholding such marriages where genuine prior intent is established, give effect to these deeply personal wishes.

The Role of the Prior Relationship Between A and Y

In this specific case, the Supreme Court noted that A and Y had been "sexually involved with the aim of future marriage". This factual element likely served as strong evidence supporting the genuineness of A's expressed marital intent while he was in the hospital.

However, legal commentators suggest that such a specific type of prior relationship should not be seen as an indispensable legal requirement for validating all deathbed marriages. If clear and convincing evidence of marital intent can be established through other means (e.g., reliable testimony, written declarations made while lucid), the absence of a long-term cohabitation or even a prior sexual relationship might not necessarily be fatal to the validity of a deathbed marriage, especially if other circumstances strongly point to a genuine desire to marry. The nature of the prior relationship is more of an evidentiary factor contributing to the assessment of intent rather than a strict legal prerequisite.

Unresolved Questions and the Evolving Scope

While this 1970 judgment and its 1969 predecessor provided significant guidance, some questions regarding the precise scope and limits of the principle remain subjects of academic discussion. For instance:

- What if the individual had passed away before the marriage registration was officially accepted by the authorities? The 1969 Supreme Court precedent appeared to suggest this would invalidate the marriage, but some legal scholars have argued for the possibility of validity even in such cases. This specific point remains a complex issue.

- How might this principle apply to other types of status-changing legal acts, such as divorce by agreement or adoption, if one party becomes unconscious before the registration is finalized? The specific considerations and policy goals might differ for acts that create a status versus those that dissolve one.

Conclusion: Honoring Final Intentions in End-of-Life Marriages

The Supreme Court of Japan's decision of April 21, 1970, solidified and importantly extended the principle that a marriage can be validly registered and recognized even if one of the parties is unconscious at the moment of official acceptance. The ruling hinges on the presence of a clear, genuine, and unrevoked marital intent expressed by that party while they were conscious and capable of forming such an intent, coupled with the due preparation of the marriage registration based on that intent.

This judgment reflects a compassionate legal approach that seeks to honor an individual's last considered wishes concerning their marital status, especially in the poignant circumstances of end-of-life situations where the legal effects of marriage can carry profound personal and familial importance. It carefully balances the formal requirements of marriage registration with a substantive understanding of marital intent, ultimately prioritizing the clear, expressed will of the individual when faced with the finality of death.