Untangling Family Trees: Japanese Supreme Court on Establishing Parent-Child Links Across Borders

Date of Judgment: January 27, 2000

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

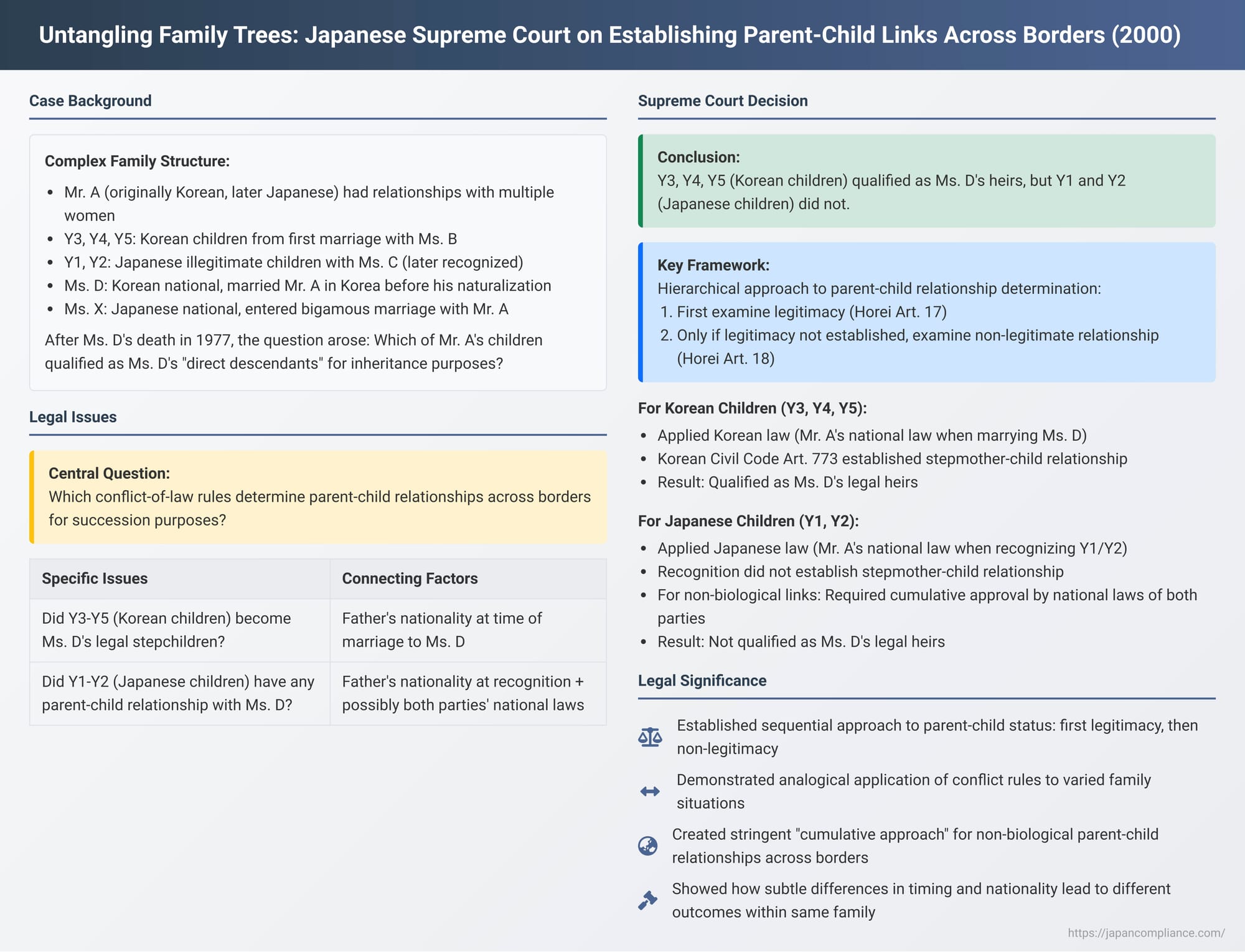

International family law cases often present deeply complex scenarios, requiring courts to navigate differing national laws to determine personal status and rights. A Japanese Supreme Court decision from January 27, 2000, provides a detailed illustration of this, specifically focusing on how Japanese private international law (PIL) rules are applied to establish parent-child relationships for the purpose of succession. This case, involving a family with Korean and Japanese members and a history of multiple relationships and changes in nationality, demonstrates the meticulous, step-by-step analysis required. (This same multifaceted case was also discussed in a previous blog post concerning the "preliminary question" doctrine in PIL; this post focuses on the specific rules for establishing parent-child relationships.)

Recap of the Central Issue: Who Inherits from Wife D?

The intricate facts revolve around Mr. A (originally Korean, later naturalized Japanese as Okayama Shoki), his various relationships, and his children:

- Mr. A had three children (Y3, Y4, Y5, all Korean nationals) with his first Korean wife, Ms. B. He divorced Ms. B.

- He also had two illegitimate children (Y1, Y2, both Japanese nationals) with a Japanese woman, Ms. C.

- Mr. A later married Ms. D (Ko Rok-Son, a Korean national) in Korea. This marriage was not recorded in Mr. A's Japanese family register when he naturalized as Japanese shortly thereafter.

- After naturalizing, Mr. A formally recognized his children Y1 and Y2.

- Mr. A subsequently entered into a bigamous marriage with Ms. X (a Japanese woman), with whom he lived along with Y1 and Y2.

- Mr. A died in 1970. His Korean wife, Ms. D, died in 1977.

The primary legal issue in this segment of the case was determining which of Mr. A's children (Y1, Y2, Y3, Y4, Y5) could be considered "direct descendants" of Ms. D for the purpose of inheriting from Ms. D's estate. Under Japanese PIL, Ms. D's succession was governed by Korean law (her national law at death), which designated "direct descendants" as first-order heirs. The critical step was to establish, under Japanese PIL, whether a legally recognized parent-child relationship existed between Ms. D and each of these children.

The Supreme Court's Step-by-Step Choice-of-Law Analysis for Parent-Child Status

The Supreme Court laid out a precise methodology for determining parent-child relationships in a conflicts-of-law context, based on the old Act on Application of Laws (Horei):

1. Hierarchical Approach: Legitimacy First, Then Non-Legitimacy

The Court ruled that when a parent-child relationship is in question, the first step is to examine whether a legitimate parent-child relationship exists. This is determined under the choice-of-law rules pertaining to legitimacy (primarily Horei Article 17, concerning legitimacy by birth, or applied by analogy for legitimacy acquired through other means).

Only if legitimacy is not established under this initial analysis should the court proceed to consider whether a non-legitimate parent-child relationship (e.g., through recognition) exists, applying the relevant choice-of-law rules for such relationships (Horei Article 18, or applied by analogy for other forms of non-legitimate parentage). This structured approach is based on the idea that legitimacy and non-legitimacy are complementary, and legitimacy is generally considered more favorable for the child.

2. Determining Legitimacy (and Step-Parent Relationships):

- For Y3, Y4, and Y5 (Mr. A's Korean children with his first wife, B):

- The question was whether Mr. A's subsequent marriage to Ms. D resulted in Y3, Y4, and Y5 becoming Ms. D's legitimate stepchildren with rights to inherit from her.

- The Supreme Court held that the applicable law for this determination was the national law of Mr. A (Ms. D's husband) at the time of his marriage to Ms. D. Since Mr. A was still a Korean national when he married Ms. D in September 1961, Korean law applied.

- Under the pre-1990 Korean Civil Code (specifically Article 773), a "stepmother-child relationship" (継母子関係 - keiboshi kankei) was indeed formed between Ms. D and Y3, Y4, Y5. This relationship treated them similarly to Ms. D's own legitimate children for inheritance purposes.

- Result: Y3, Y4, and Y5 were considered Ms. D's legal heirs.

- For Y1 and Y2 (Mr. A's Japanese children with Ms. C, recognized by Mr. A):

- The question was whether Mr. A's recognition of Y1 and Y2 (which occurred after Mr. A had married Ms. D and after he had naturalized as a Japanese citizen) made Y1 and Y2 the legitimate children of Ms. D.

- The applicable law for this determination was the national law of Mr. A (the recognizing father) at the time of the recognition. Mr. A recognized Y1 and Y2 in March 1963, by which time he was a Japanese national. Therefore, Japanese law applied.

- Under Japanese law, a father's recognition of his illegitimate children does not, by itself, make those children the legitimate children of his wife (their stepmother, Ms. D).

- Result: Y1 and Y2 were not considered Ms. D's legitimate children.

3. Establishing Non-Legitimate Parent-Child Links (Specifically for Y1, Y2 with Ms. D):

Since Y1 and Y2 were not found to be Ms. D's legitimate children, the Supreme Court next considered whether any other form of non-legitimate parent-child relationship could be established between Ms. D and Y1/Y2, particularly in light of Mr. A's recognition of Y1/Y2. There was no biological link between Ms. D and Y1/Y2.

- The Court noted that Horei Article 18(1) primarily addresses the establishment of parentage between the recognizing person and the recognized child. It does not directly cover the creation of a parent-child relationship between the recognized child and the recognizing person's spouse (Ms. D), especially where no blood ties exist.

- For establishing a parent-child relationship by means other than birth or direct recognition, particularly between individuals not biologically related (like Ms. D and her husband's children Y1/Y2 from another union), the Supreme Court invoked the "spirit" (法意 - hōi) of Horei Articles 18(1) and 22 (the latter being a general provision for family relations not otherwise covered).

- It held that such a non-biological parent-child relationship could be recognized only if the laws of both the potential parent (Ms. D, so her national law: Korean law) AND the children (Y1 and Y2, so their national law: Japanese law), at the time of the event potentially creating such a link (here, Mr. A's recognition of Y1/Y2), both affirmed the creation of such a parent-child relationship.

- Result: The Court found that Japanese law does not establish a parent-child relationship between a stepmother (Ms. D) and her husband's recognized illegitimate children (Y1, Y2) merely as a consequence of the husband's act of recognition. Since one of the required laws (Japanese law) did not affirm such a relationship, the Court concluded that no parent-child link existed between Ms. D and Y1/Y2, without needing to conduct a detailed examination of Korean law on this specific point. Consequently, Y1 and Y2 were not considered Ms. D's heirs.

Key Principles and Commentary Insights

This complex Supreme Court decision offers several important takeaways regarding Japanese private international law for parent-child relationships:

- Sequential Application of Rules: The Court mandated a clear order: first, assess legitimacy (Horei Art. 17 / Act on General Rules for Application of Laws Art. 28); if negative, then assess non-legitimate parentage (Horei Art. 18 / Act on General Rules for Application of Laws Art. 29). This hierarchical approach is now well-established.

- Analogical Application for Legitimacy by Subsequent Events: The old Horei Art. 17, literally referring to the child's birth, was applied by analogy to situations where legitimacy might be acquired later (like through a step-parental relationship arising from marriage). Professor Aoki's commentary suggests that under the current Act on General Rules for Application of Laws, which has a specific provision for legitimation by subsequent marriage or recognition (Article 30), Article 30 might be a more appropriate candidate for analogical application in similar cases, as it also strongly considers the child's interests by offering alternative connecting factors.

- Cumulative Requirements for Certain Non-Biological Links: For establishing non-biological parent-child relationships not directly covered by recognition rules, the Supreme Court imposed a stringent requirement of affirmation by the national laws of both parties involved. Academic commentary has discussed whether this "cumulative" approach is always textually mandated or the most conducive to establishing parentage, especially since it can make such relationships harder to form legally across borders. Professor Aoki, for example, questions the necessity of invoking the general family relations article (Horei Art. 22) in addition to the principles of the non-legitimate parentage article (Horei Art. 18).

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of January 27, 2000, meticulously demonstrates the application of Japanese private international law to determine parent-child status in a convoluted international family setting. It highlights the importance of specific connecting factors (like the parent's national law at a particular event), the hierarchical application of different PIL rules for legitimacy and non-legitimacy, and the courts' willingness to use analogical reasoning to apply existing rules to novel situations. This case underscores how varying outcomes can result for different children within the same extended family based on their own nationalities, their parents' nationalities at critical junctures, and the specific legal acts (marriage, recognition, etc.) that shape their relationships under the intricate web of conflict of laws rules.