Untangling Double Taxation: The Japanese Supreme Court on Life Insurance Annuities and Non-Taxable Income

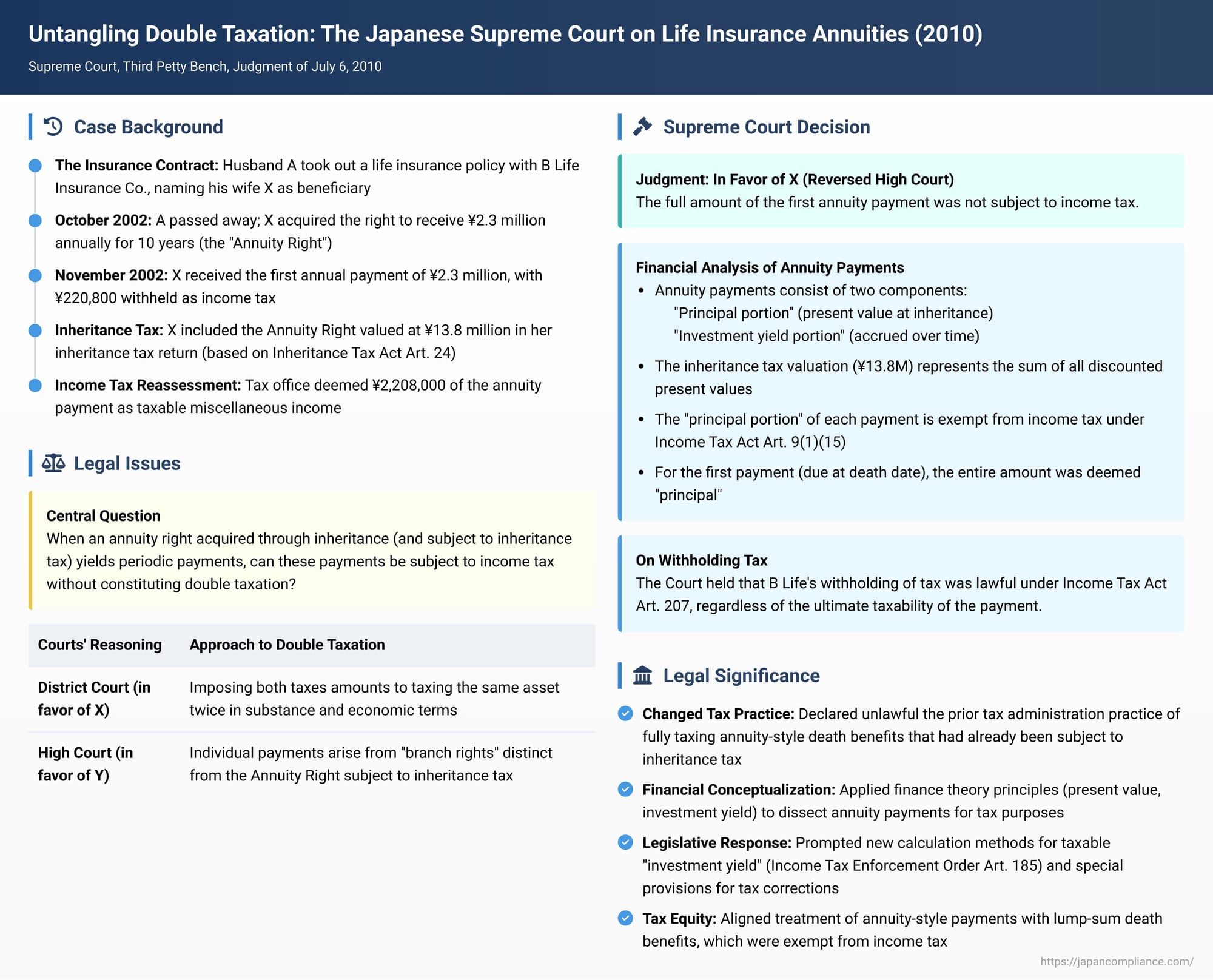

Case: Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of July 6, 2010 (Heisei 20 (Gyo-Hi) No. 16: Action for Rescission of Income Tax Reassessment Disposition) – Commonly known as the "Life Insurance Annuity Double Taxation Case"

Introduction

On July 6, 2010, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark judgment that significantly impacted the taxation of life insurance proceeds paid out as annuities. This case, often referred to as the "Life Insurance Annuity Double Taxation Case" (生保年金二重課税事件), addressed the critical issue of potential double taxation when an annuity right, acquired through inheritance and already subject to inheritance tax, subsequently yields periodic annuity payments that become subject to income tax. The Court's decision provided a nuanced interpretation of Japan's non-taxable income provisions, particularly focusing on the economic substance of annuity payments and the legislative intent to avoid taxing the same economic value twice under different tax regimes.

The central question was whether annual payments received by a widow, X, from a life insurance policy taken out and paid for by her deceased husband, A, were subject to income tax, given that the right to receive these annuity payments (the Annuity Right) had already been valued and included in her inheritance tax assessment. X argued that subjecting these payments to income tax constituted impermissible double taxation.

Facts of the Case

The appellant, X, was the widow of A. A had entered into a life insurance contract with B Life Insurance Mutual Company (hereinafter "B Life"), naming himself as the insured and X as the beneficiary. The policy included a special rider for annuity payments, and A had borne the cost of the insurance premiums. A passed away in October 2002. As a result of A's death, X acquired the right to receive a special annuity of 2.3 million yen annually for a period of 10 years (this right is hereinafter referred to as "the Annuity Right").

In November 2002, X received the first of these special annuity payments (hereinafter "the Annuity Payment") from B Life, amounting to 2.3 million yen, from which 220,800 yen had been withheld as income tax pursuant to Article 208 of the Income Tax Act. In her income tax return for the 2002 tax year (including a subsequent claim for correction), X did not include the amount of the Annuity Payment in her taxable income. However, for her inheritance tax declaration related to A's estate, X had included the value of the Annuity Right, calculated at 13.8 million yen according to the provisions of the old Inheritance Tax Act Article 24, Paragraph 1, Item 1, in the taxable base for inheritance tax.

The director of the competent tax office subsequently issued a reassessment of X's 2002 income tax. This reassessment determined that an amount of 2,208,000 yen – calculated by deducting 92,000 yen (deemed as necessary expenses based on the premiums A had paid) from the 2.3 million yen Annuity Payment – constituted miscellaneous income (雑所得, zatsu shotoku) for X. X initiated legal proceedings against the government, Y (the appellee), seeking the cancellation of this reassessment and related dispositions.

The Nagasaki District Court, as the court of first instance, ruled in favor of X. It reasoned that the valuation of an annuity right for inheritance tax purposes essentially represents the present value (or an approximation thereof) of the economic benefits to be received from future annuity payments at the time of acquisition. Therefore, imposing inheritance tax on this value and then subsequently imposing income tax on the individual annuity payments would clearly amount to taxing the same asset twice in substance and economic terms. The District Court concluded that this was impermissible under the intent of Article 9, Paragraph 1, Item 15 of the Income Tax Act (old version, now Item 17; hereinafter references to this article are to the old version).

However, the Fukuoka High Court, on appeal, overturned the District Court's decision and ruled in favor of Y, the government. The High Court held that the term "insurance proceeds" as used in Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Inheritance Tax Act (which deems certain life insurance proceeds as acquired by inheritance) refers to the insurance claim right itself. It found that X's Annuity Right fell under this definition and was thus subject to inheritance tax. However, the High Court differentiated the individual Annuity Payment received by X, stating that it was legally distinct from the Annuity Right and arose from a "branch right" (支分権, shibunken) based on the Annuity Right after A's death. Consequently, the High Court concluded that the Annuity Payment itself was not the "insurance proceeds" deemed acquired by inheritance for the purposes of the income tax exemption, and therefore, it did not qualify as non-taxable income under Income Tax Act Article 9, Paragraph 1, Item 15. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's judgment and ruled in favor of X, effectively reinstating the core reasoning of the first instance court but with a more detailed financial analysis.

Interpretation of Income Tax Act Article 9, Paragraph 1, Item 15 (Non-Taxable Income from Inheritance)

The Court began by interpreting the scope of non-taxable income derived from inheritance:

- The phrase "what is acquired through inheritance, bequest, or gift from an individual" as stipulated in Article 9, Paragraph 1, Item 15 of the Income Tax Act does not refer to the inherited (or gifted) property itself. Instead, it refers to the income that accrues to the person as a result of the acquisition of said property.

- This "income" is equivalent to the economic value corresponding to the value of the acquired property at the time of its acquisition. This economic value is precisely what becomes the taxable base for inheritance tax or gift tax.

- Therefore, the Court elucidated that the purpose of Item 15 is to prevent double taxation. It achieves this by exempting from income tax any economic value that has already been subject to inheritance tax or gift tax.

Interpretation of Inheritance Tax Act Provisions (Articles 3 and 24)

The Court then analyzed the relevant Inheritance Tax Act provisions regarding life insurance proceeds paid as annuities:

- Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Inheritance Tax Act provides that when an heir acquires life insurance proceeds due to the death of the decedent (the insured), such proceeds (to the extent attributable to premiums borne by the decedent) are deemed to have been acquired by inheritance. The Court affirmed that "insurance proceeds" in this context includes those received in the form of an annuity. When paid as an annuity, these "insurance proceeds" specifically refer to the fundamental claim right to receive the annuity (the Annuity Right), which is considered a right related to a periodic payment contract under Article 24, Paragraph 1 of the Inheritance Tax Act.

- For fixed-term annuity rights, such as the one X acquired, Article 24, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Inheritance Tax Act prescribes a method for calculating its value for inheritance tax purposes: the total amount of annuity payments to be received over the remaining term is multiplied by a prescribed ratio based on that remaining term. The Supreme Court interpreted this assessed value as being equivalent to the fair market value of the annuity right at the time of its acquisition (as per Article 22 of the Inheritance Tax Act). This fair market value, in turn, represents the sum total of the present values of all future annuity payments, discounted back to the date of the decedent's death.

- Crucially, the Court explained that the difference between this inheritance tax valuation (the sum of present values) and the total nominal sum of all annuity payments to be received over the entire term is, in economic terms, equivalent to the total investment yield that would accrue if the present values of each individual annuity payment were treated as principal amounts invested over time.

- Following this logic, the Court concluded that the portion of each individual annuity payment that corresponds to its present value (calculated at the time of inheritance) is economically identical to the value that was subjected to inheritance tax. Consequently, this "principal" portion of each annuity payment is non-taxable for income tax purposes under Article 9, Paragraph 1, Item 15 of the Income Tax Act.

Application to X's Case

Applying these principles to the facts of X's situation:

- X's Annuity Right was a fixed-term annuity.

- The first Annuity Payment X received had a payment date corresponding to the date of A's death.

- Given this timing, the Court reasoned that the entire amount of this first payment (2.3 million yen) must be considered its present value at the time of A's death, as no time would have elapsed for any investment yield to accrue.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court held that the full amount of the first Annuity Payment was not subject to income tax, and the tax office's reassessment imposing income tax on it was impermissible.

Legality of Withholding Tax

Despite finding the Annuity Payment non-taxable for income tax, the Court addressed the issue of the withholding tax that B Life had deducted:

- Article 207 of the Income Tax Act requires those who pay annuities based on life insurance contracts, etc., to withhold income tax. The Court found that this obligation applies regardless of whether the annuity (or a portion thereof) is ultimately determined to be subject to income tax as part of the recipient's taxable income under the Act. The payer is required to withhold the amount prescribed in Article 208 and remit it to the government as income tax.

- Consequently, the Court deemed B Life's withholding of tax from X's Annuity Payment to be lawful. X would then be entitled to claim this withheld amount as a credit against her calculated income tax liability or receive a refund of all or part of it through her income tax return filing and any subsequent correction procedures.

Commentary Insights

This Supreme Court judgment has been extensively analyzed and has significant implications for both substantive tax law and tax procedure in Japan.

Significance of the Ruling

The decision carries importance on two main fronts:

- Substantive Impact: It declared that the portion of annuity-style death benefit payments which has already been subjected to inheritance tax (as part of the valuation of the annuity right) is non-taxable for income tax purposes under the old Income Tax Act Article 9, Paragraph 1, Item 15 (now Article 17). This effectively rendered unlawful the prior tax administration practice of taxing such amounts as income.

- Procedural Impact: It affirmed the legality of the withholding tax mechanism under Article 208, even in situations where the underlying income (or part of it) is ultimately found to be non-taxable for income tax purposes. This aligns with previous Supreme Court precedent on the nature of withholding tax relationships.

Previous Tax Practice and the Core Dispute

Prior to this ruling, the tax administration's practice was to treat lump-sum death benefits and annuity-style death benefits differently:

- Annuity Payments: (a) Inheritance tax was levied on the assessed value of the annuity right (often a relatively low valuation under the specific rules of Inheritance Tax Act Article 24). (b) Subsequently, income tax was imposed on each annual annuity payment received, after deducting a small amount for necessary expenses calculated based on the premiums paid by the deceased.

- Lump-Sum Payments: (a) Inheritance tax was levied on the full amount of the lump-sum payment. (b) However, no income tax was subsequently imposed, as it was considered exempt under Income Tax Act Article 9, Paragraph 1, Item 15.

The substantive core of the dispute in this case was the legitimacy of this differential tax treatment, which effectively subjected annuity-style payments to both inheritance and income tax, while lump-sum payments faced only inheritance tax.

Understanding the Judgment: A Finance Theory Perspective

Legal commentators have noted that a finance theory perspective, particularly the concept of an asset's value being the "sum of the discounted present values of its future cash flows," is beneficial for understanding the Supreme Court's reasoning.

- The First Instance Court (Nagasaki District Court) took the view that taxing both the annuity right (for inheritance tax) and the subsequent annuity payments (for income tax) amounted to "substantively and economically taxing the same asset twice." This implied that the "entire annuity" in an economic sense was the subject of inheritance tax, and thus subsequent payments should also be free from income tax.

- The High Court (Fukuoka High Court), conversely, focused on the legal distinction between the annuity right as a "basic right" (基本債権, kihon saiken) subject to inheritance tax, and the individual annuity payments arising from "branch rights" (支分権, shibunken). It deemed these legally distinct and concluded that the individual payments were not covered by the income tax exemption, thereby upholding the existing tax practice.

- The Supreme Court adopted a more sophisticated financial analysis. It conceptualized each annuity payment (e.g., the 2.3 million yen) as comprising two components: (1) a "principal portion" (representing its present value at the time of inheritance) and (2) an "investment yield portion." According to the Supreme Court, inheritance tax is levied on the sum of these "principal portions." The "investment yield portion," however, could potentially be subject to income tax.

The Court interpreted the 13.8 million yen inheritance tax valuation of the Annuity Right (which was calculated as the total nominal future payments of 23 million yen multiplied by a statutory factor of 0.6 under the old Inheritance Tax Act Article 24) as representing the sum of these discounted present values. The difference between this value and the total nominal payments (23 million yen - 13.8 million yen = 9.2 million yen) was positioned as the total "investment yield" on the 13.8 million yen "principal". (Commentary notes that the statutory discount rate under the old rules was approximately 13.7% per annum, which was significantly out of sync with actual market rates at the time of the ruling; the valuation method was reformed in 2010 to better reflect economic reality).

The Supreme Court concluded that since the "principal portion" of the annuity payments had already been subject to inheritance tax, it should be exempt from income tax under Article 9, Paragraph 1, Item 15. For the first annuity payment, which was due on the date of A's death, the Court reasoned that the entire amount constituted this "principal portion" (as no time had passed for investment yield to accrue), making it entirely non-taxable for income tax.

This reasoning implies that for subsequent annuity payments, the "investment yield portion" would be subject to income tax. The commentary suggests the Supreme Court's approach can be understood as treating the annuity right as a bundle of zero-coupon bonds with different maturity dates, with the investment yield component increasing in later payments.

While the High Court primarily focused on the legal distinctions between basic and branch rights, both the First Instance Court and the Supreme Court incorporated financial perspectives into their analyses. The First Instance Court's approach, by potentially exempting the yield portion as well, leaned towards a consumption-type income concept. The Supreme Court, by not ruling out income tax on the yield portion, adopted a stance more aligned with a comprehensive income concept. The Supreme Court was also seen by commentators as focusing on achieving "tax equity" between lump-sum and annuity payments of death benefits.

Scope and Implications of the Ruling Beyond Annuities

The principles enunciated in this judgment have sparked discussion about their applicability to other types of inherited assets:

- Inherited Assets Sold by Heirs: When an heir sells an inherited asset, their cost basis for calculating capital gains is generally the deceased's original cost basis, stepped up under certain conditions (Income Tax Act Article 60, Paragraph 1). One view is that since any unrealized appreciation during the deceased's holding period was arguably factored into the inheritance tax valuation, only the appreciation during the heir's holding period should be subject to income tax upon sale.

- However, lower court decisions have generally held that the Income Tax Act intends for gains accrued during the deceased's lifetime but realized by the heir upon sale to be subject to income tax in the hands of the heir, separate from the inheritance tax levied on the asset's value at death.

- The Japanese government reportedly understood the direct scope of this Supreme Court ruling to be limited to inherited assets valued under Article 24 of the Inheritance Tax Act (i.e., periodic payment rights like annuities). It maintained the view that unrealized gains on other assets like land or stocks, inherited and then sold by an heir, could still be subject to income tax upon realization under Article 60, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act. For certain types of accrued but unrealized income of the deceased (like accrued interest on time deposits), where explicit provisions for taxing it to the heir upon realization were previously lacking, the government introduced Income Tax Act Article 67-4 in 2011 as a "confirmatory measure".

Legislative and Administrative Responses Post-Judgment

Following the Supreme Court's decision:

- In 2010, a new method for calculating the taxable "investment yield portion" (as miscellaneous income) of such annuities was established by Cabinet Order (Income Tax Enforcement Order Article 185), which notably adopted a simplified simple interest calculation method.

- In 2011, special legislative measures were introduced to allow for the correction of tax assessments related to such annuity income for the preceding 10 years, including provisions for special refunds (these special provisions, formerly in the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation, were subsequently deleted in 2019).

Broader Implications and Discussion

The "Life Insurance Annuity Double Taxation Case" touches upon several enduring themes in tax law:

- Principle Against Double Taxation: The judgment reinforces the underlying principle of avoiding the imposition of different types of taxes (here, inheritance and income tax) on the same underlying economic value or asset.

- Economic Substance and Financial Analysis: The Supreme Court's willingness to dissect annuity payments into "principal" and "investment yield" components using financial concepts like present value demonstrates a move towards analyzing economic substance over strict legal formalism in certain tax contexts.

- Taxation of Unrealized Gains at Death: The case indirectly relates to the broader international debate on how to treat unrealized capital gains at the time of death – whether they should be taxed then, or if the heir should receive a carryover basis or a stepped-up basis. Japan's system, as interpreted here for annuities, involves taxing the value at death via inheritance tax and then potentially taxing subsequent income/yield.

- Balancing Precision and Simplicity: The subsequent adoption of a simplified (simple interest) method for calculating the taxable yield portion of annuities reflects the common tension in tax administration between achieving precise economic measurement and the need for rules that are practical and relatively simple to apply.

The "Considerations for Discussion" in the provided commentary raise further questions, such as whether the ruling's logic extends to assets like perpetual bonds, land, stocks, or patents, how alternative methods for allocating investment yield annually could be devised, and the fundamental relationship between inheritance tax and income tax. These remain areas of ongoing academic and policy discussion.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's July 6, 2010, decision in the "Life Insurance Annuity Double Taxation Case" marked a significant clarification in Japanese tax law, preventing the double taxation of the principal component of inherited life insurance annuities. By employing a financial analysis that distinguished the inherited capital (present value) from subsequent investment yield, the Court provided a principled basis for exempting the former from income tax while implicitly allowing for the taxation of the latter. This judgment led to important legislative and administrative adjustments and continues to inform discussions on the interaction between inheritance tax and income tax in Japan, particularly concerning the economic value passed from one generation to the next.