Unregistered Testamentary Gifts vs. Heir's Creditors: A 1964 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Devises and Registration

Date of Judgment: March 6, 1964 (Showa 39)

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case No. Showa 36 (o) No. 338 (Third-Party Objection Suit)

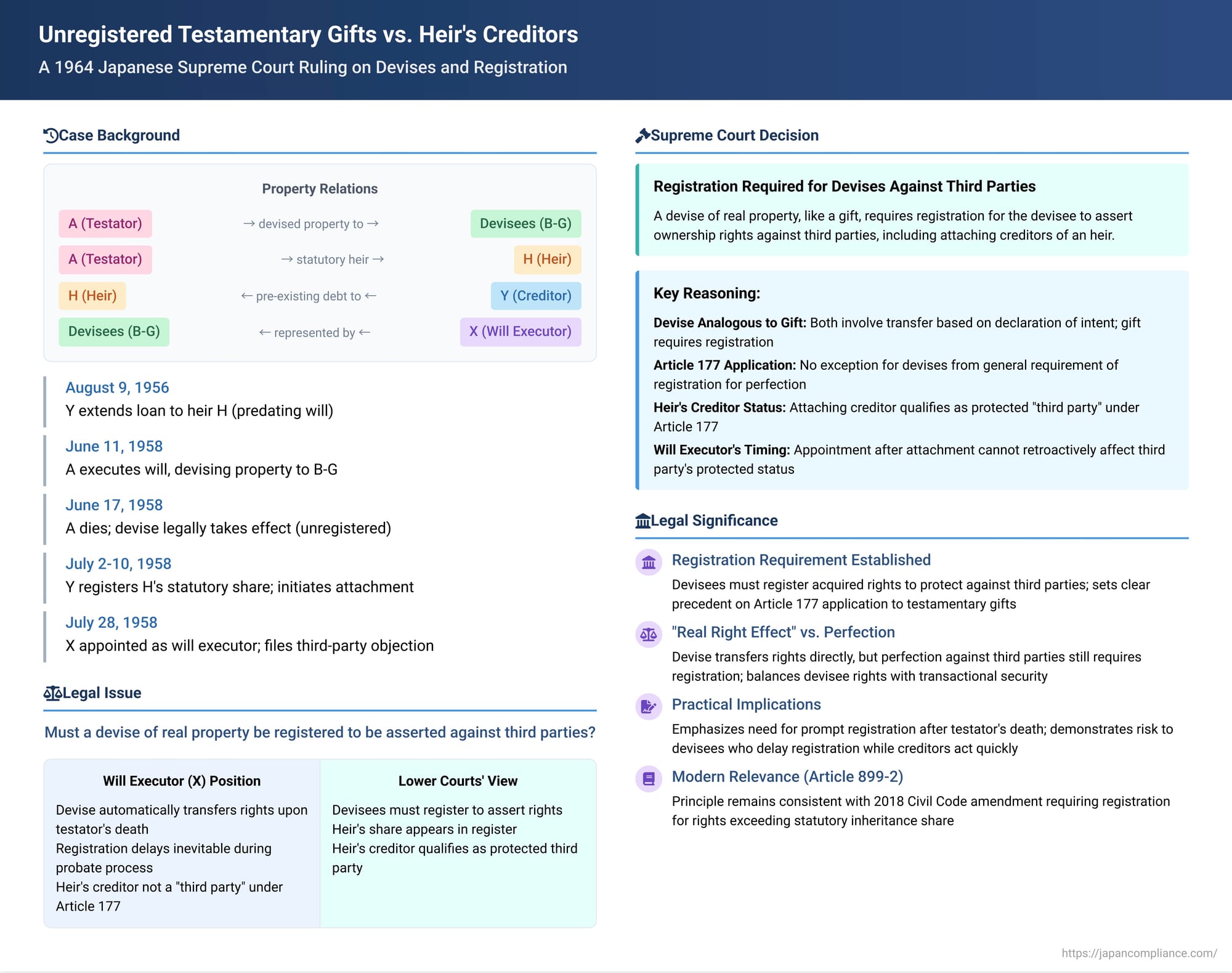

When a person receives real property through a testamentary gift (a "devise" or 遺贈 - izō in Japanese), a critical question arises regarding their rights against third parties, particularly if the transfer of ownership based on the devise has not yet been formally registered in the property records. Can a devisee assert their rights against a creditor who, after the testator's death but before the devise is registered, attaches an heir's apparent statutory share in that same property? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this fundamental issue concerning devises and the necessity of registration in its decision on March 6, 1964.

Facts of the Case: A Devise, an Heir's Debt, and a Race to Secure Rights

The case involved a parcel of real estate ("the Property") formerly owned by A.

- The Will and Devise: On June 11, 1958, A executed a will in which he devised the Property to six named individuals: B, C, D, E, F, and G (collectively, the "Devisees").

- A's Death and Effectiveness of Devise: A passed away shortly thereafter, on June 17, 1958. Upon A's death, the devise legally took effect, notionally transferring A's ownership of the Property to the Devisees. However, an ownership transfer registration reflecting this devise was not immediately made.

- The Heir and His Pre-existing Debt: H was one of A's legal heirs. If A had died intestate or if the devise was ineffective, H would have been entitled to a statutory co-ownership share in the Property. Y (Nonaka Sangyo Kabushiki Kaisha, a company, the defendant/appellee) was a creditor of H, holding a claim based on a loan that Y had extended to H on August 9, 1956—notably, this loan predated both A's will and A's death.

- Creditor's Actions After A's Death: Following A's death, Y took swift action to secure its claim against H:

- On July 2, 1958, Y, acting by way of subrogation (a legal mechanism allowing a creditor to exercise certain rights of their debtor), procured an inheritance registration for the Property. This registration was made in H's name and reflected H's statutory co-ownership share in the Property (which the judgment indicates was 1/4). This registration did not reflect the devise to the Devisees.

- Subsequently, Y initiated compulsory auction (foreclosure) proceedings against H's registered 1/4 statutory share. A notice of this auction application was formally entered in the property register on July 10, 1958.

- Appointment of Will Executor: Shortly thereafter, on July 28, 1958, X (Sadajuro Hidaka, the plaintiff/appellant) was officially appointed as the executor of A's will.

- The Lawsuit by the Will Executor: X, in his capacity as the will executor representing the interests of the Devisees, filed a "third-party objection lawsuit" (第三者異議の訴え - daisansha igi no uttae) against Y. X sought a court order to prevent the compulsory auction of H's purported share in the Property. The basis of X's claim was that, due to A's devise, the Property actually belonged to the Devisees, and therefore H (the debtor heir) held no inheritable interest in it that Y could validly attach.

- Lower Court Ruling: The High Court had dismissed X's claim. The presumed reasoning was that the Devisees, having failed to register the transfer of ownership to them by devise, could not assert their rights against Y, who had attached H's apparent (and registered) statutory share as a creditor.

- Appeal by X to the Supreme Court: X appealed to the Supreme Court. X argued, among other points, that a specific devise should, by its nature, automatically and indefeasibly transfer property rights to the devisee upon the testator's death. X also highlighted the practical reality that will execution processes, including probate (検認 - kennin), often cause delays, making immediate registration by devisees difficult. Therefore, X contended that an attaching creditor of an heir, like Y, should not be considered a "third party" under Article 177 of the Civil Code against whom registration is a prerequisite for asserting the devisee's rights.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Registration Required for Devises Against Third Parties

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby affirming the High Court's decision that the devise needed to be registered to be asserted against Y.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Analogy Between Devise and Gift (贈与 - Zōyo):

The Court drew a strong analogy between a devise and an inter vivos gift. It referenced a prior Supreme Court decision (Showa 33.10.14 - October 14, 1958) which established that even if an owner gifts real estate to another person, a fully exclusive and perfected change in legal rights does not occur (and the donor is not considered entirely divested of all connection to the property vis-à-vis third parties) until the transfer of ownership based on the gift is duly registered.

A devise, the Court stated, is essentially a declaration of the testator's intent to grant property rights to a devisee, with the testator's death acting as the condition (an uncertain future event) for the devise to take effect. In terms of effecting a change in real property rights through a declaration of intent, a devise is fundamentally no different from a gift. - Registration as a Perfection Requirement (対抗要件 - Taikō Yōken) for Devises:

Given this similarity, the Court held that even when a devise becomes legally effective upon the testator's death, a fully exclusive and perfected change in property rights does not arise (vis-à-vis third parties) until the ownership transfer based on the devise is registered.

Article 177 of the Civil Code lays down the general principle that for acquisitions, losses, or alterations of real property rights, registration is required as a "perfection requirement" (or "means of asserting against third parties") to make these changes effective against such third parties.

The Supreme Court found no compelling reason to treat devises as an exception to this broad rule. Therefore, in the context of devises of real property, just as in cases involving competing transactions like double sales, registration is necessary to perfect the transfer of property rights by devise and to assert those rights against third parties. - Application to the Facts of the Case:

- In this instance, the transfer of the Property to the Devisees by A's will had not been registered.

- In the intervening period, Y, acting as a creditor of H (one of A's legal heirs who would have had a statutory share in the Property had there been no effective devise), initiated compulsory execution proceedings against H's apparent statutory share. This share had been registered (albeit at Y's instigation through subrogation), and the auction application was duly noted in the property register.

- The Supreme Court held that Y, as an attaching creditor who had levied execution against H's registered statutory share in the Property, qualified as a "third party" within the meaning of Article 177 of the Civil Code.

- Consequently, the Devisees (represented by X, the will executor) could not assert their ownership rights acquired through the unregistered devise against Y.

- The Court also noted that the subsequent appointment of X as the will executor (which occurred after Y's attachment was registered) did not alter Y's pre-existing status as a protected third party under Article 177.

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1964 Supreme Court judgment is a foundational ruling in Japanese law concerning the interplay of testamentary dispositions (devises) of real property, the rights of devisees, and the requirements of the property registration system.

- Registration Requirement for Devises Firmly Established: The decision unequivocally established that a devise of real property, much like other inter vivos transfers of real property rights (such as gifts or sales), requires registration for the devisee to be able to assert their acquired ownership rights against third parties. This includes third parties like attaching creditors of an heir who might otherwise have a statutory claim to the property.

- Devise Treated Analogously to Gift for Registration Purposes: The Court's direct analogy of a devise to a gift was a key element in its reasoning. Since it was already established that gifts of real property require registration for perfection against third parties, the Court extended this logic to devises, emphasizing that both involve a transfer of property rights based on a declaration of intent.

- The "Real Right Effect" (物権的効力 - Bukkenteki Kōryoku) of a Devise vs. Perfection Against Third Parties: Legal commentary points out that while a specific devise is generally understood to have a "real right effect"—meaning it is considered to directly transfer the property right from the testator to the devisee upon the testator's death, without necessarily requiring a separate act of fulfillment by the heirs—this "real right effect" primarily describes the mechanism and directness of the transfer between the parties involved in the devise. It does not inherently mean that the devisee's rights are automatically perfected against all third parties without registration. Perfection against third parties is a separate issue governed by Article 177.

- Role of Heirs or Will Executor in Registration: Even though a specific devise directly transfers rights, there remains a practical and legal necessity for the heirs of the testator, or a duly appointed will executor, to cooperate in the registration process to formally record the devisee's title in the public register. If a will executor is appointed, they typically apply for the registration jointly with the devisee. If an heir is also the devisee, they may be able to apply for registration unilaterally under certain conditions.

- Balancing Devisee's Rights with Transactional Security: The Supreme Court's decision reflects a balancing of interests. While devisees acquire rights upon the testator's death, the need to protect third parties who might rely on the state of the public register (or the apparent statutory rights of heirs if no devise is registered) and to ensure the overall security of real estate transactions led the Court to apply the general registration requirements of Article 177. Arguments about practical difficulties faced by devisees in achieving immediate registration (e.g., delays in discovering the will or completing probate procedures) were not found to be sufficient to create a broad exception to this rule. Legal commentary suggests that the gratuitous nature of many devises, when weighed against the often commercial or transactional nature of competing third-party interests, might also factor into this balance.

- Distinction from Conflicts Between Multiple Dispositions by the Testator: It's important to note, as highlighted by legal commentary, that this case involved a conflict between a devise (an act of the testator) and the rights of an heir's creditor (a relationship established through the heir, not directly by the testator concerning the same property). This is different from scenarios where there might be a conflict between two incompatible dispositions made by the testator themselves regarding the same property (e.g., a lifetime gift of a property followed by a devise of the same property to someone else, or a devise in an earlier will followed by a lifetime sale or a conflicting devise in a later will). Such scenarios could involve different legal principles, such as whether the property was even part of the estate at the time of death (Article 996 of the Civil Code) or whether a later disposition by the testator constituted an implied or explicit revocation of the earlier will (Article 1023, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code).

- Effect of Will Executor's Appointment After Attachment: The Court clarified that if a third party (like creditor Y) has already validly acquired and registered an interest (like an attachment) against an heir's apparent statutory share before the devise is registered and before a will executor might intervene, the subsequent appointment of the will executor does not retroactively divest the third party of their protected status under Article 177.

- Relevance in Light of Modern Civil Code Article 899-2: While this 1964 Supreme Court judgment established the applicability of Article 177 to devises, it's also useful to consider it in the context of the more recent 2018 amendments to the Civil Code, which introduced Article 899-2. This new article specifically addresses perfection requirements for rights acquired through "succession by inheritance," including rights obtained via a will that might alter statutory shares. Article 899-2 generally requires registration for an heir to assert rights exceeding their statutory inheritance share against third parties. Legal commentary on the 1964 devise case suggests that the primary legal basis for requiring registration for devises today continues to be Article 177 of the Civil Code, as Article 899-2's wording is primarily focused on "succession by inheritance" in a way that distinguishes it from "devise" (遺贈 - izō). Nevertheless, the underlying principle in both the 1964 judgment and Article 899-2 is consistent: rights to real property that deviate from the basic statutory inheritance framework generally require registration to be fully assertable against third parties.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1964 decision remains a significant authority in Japanese law, affirming that devisees of real property must register their acquired rights to protect them against subsequent claims by third parties, including attaching creditors of the testator's heirs. By likening devises to gifts for the purpose of registration requirements under Article 177 of the Civil Code, the Court prioritized the public's reliance on the property register and the broader principles of transactional security. This ruling underscores the importance for devisees, or the executors of wills, to act diligently in completing the necessary registration procedures to ensure the full legal protection of the rights conferred by a testamentary gift.