Unregistered Land, Public Sale, and Good Faith: When the State Can't Ignore the True Owner

Judgment Date: March 31, 1960

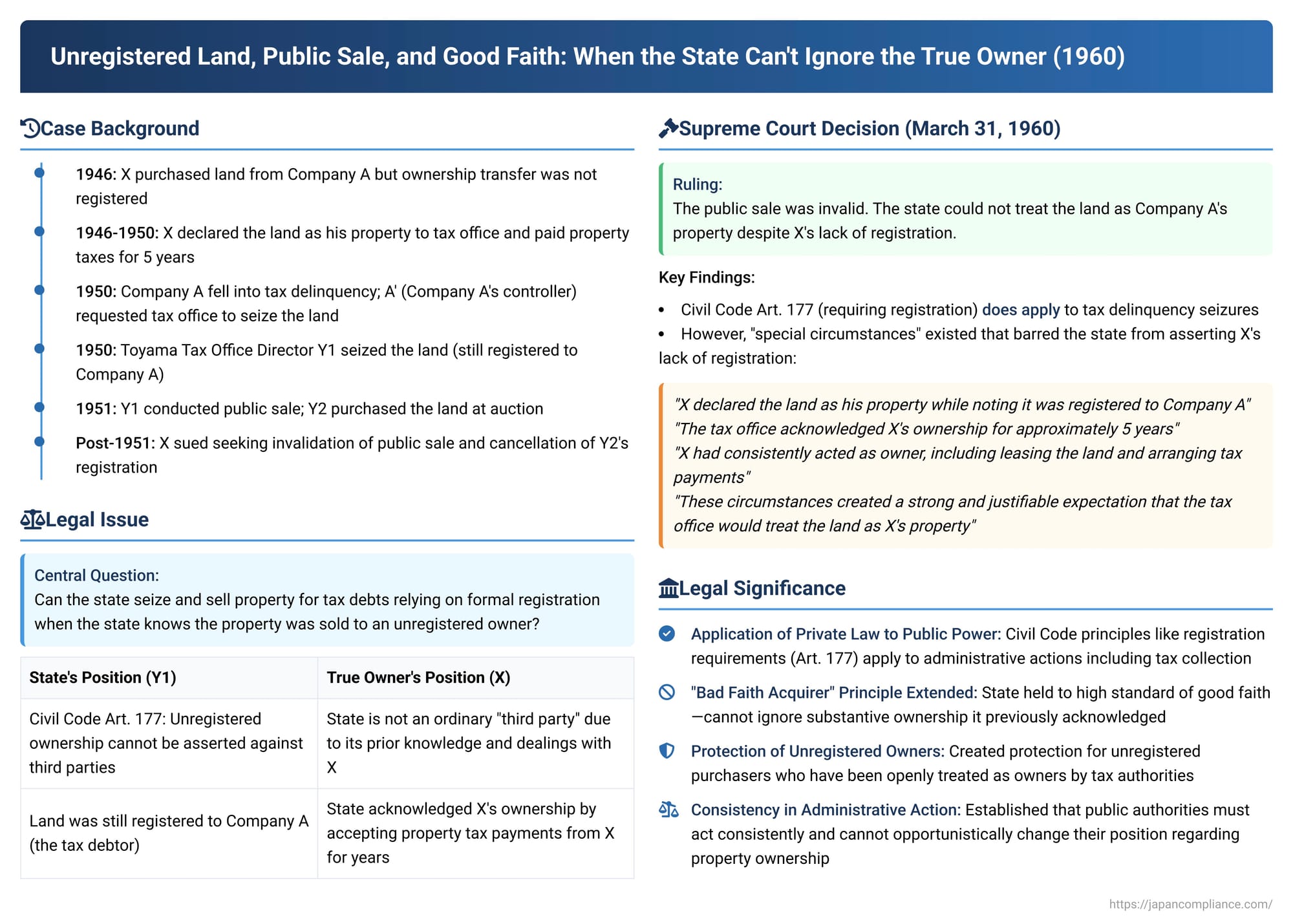

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Can the state seize and sell a piece of land to cover a company's tax debts if that land was previously sold by the company to an individual who, for various reasons, hadn't yet registered their ownership? This complex question, pitting the state's tax collection powers against an unregistered property owner's rights, was at the heart of a significant 1960 Japanese Supreme Court decision. The case highlights the application of private property law principles, specifically Article 177 of the Civil Code concerning the perfection of real rights through registration, to administrative actions like tax delinquency sales, and underscores the importance of the state acting in good faith.

The Unregistered Land and the Tax Man's Claim: A Convoluted Path

The story began in 1946 when the plaintiff, X, purchased a parcel of land ("the Land") from Company A and duly paid the purchase price. However, due to circumstances on Company A's side, the formal registration of X's ownership transfer was not completed at that time. Despite this, in the same year, X declared the Land as his own to the Uozu Tax Office Director and paid the assessed property tax.

Years later, Company A fell into tax delinquency. The Uozu Tax Office Director initially seized machinery within Company A's factory to satisfy these debts. In a twist of fate, a tax collection notice for the Land—still officially registered under Company A's name—was delivered to Company A. This brought the Land's registration status to the attention of A', the de facto controller of Company A. Seeing an opportunity, A' petitioned the Uozu Tax Office Director to seize the Land instead of the already-levied machinery. The Director agreed to this request and transferred the handling of the matter to Y1, the Toyama Tax Office Director.

In 1950, Y1 proceeded to seize the Land and had the seizure officially registered. The following year, Y1 conducted a public sale (公売処分 - kōbai shobun) of the Land. Y2 emerged as the successful bidder, and the ownership of the Land was subsequently registered in Y2's name. This seizure and public sale are collectively referred to as "the Public Sale Disposition."

Aggrieved by these actions, X filed a lawsuit. He sought two main remedies:

- A confirmation from the court that the Public Sale Disposition effectuated by Y1 (representing the State) was invalid.

- An order compelling Y2 to cancel the registration of ownership that had been transferred to Y2 as a result of the public sale.

A Twisting Legal Journey: Lower Courts and the First Supreme Court Remand

The case navigated a complex path through the Japanese court system:

- The First Instance court (Toyama District Court) ruled against X.

- On appeal, the Second Instance court (Nagoya High Court, Kanazawa Branch) reversed the decision and found in favor of X. This court reasoned that because the State (through the Uozu Tax Office) had previously treated X as the owner of the Land when he declared and paid property tax, it would be an act contrary to good faith for the State to now deny X's ownership based merely on the lack of formal registration.

- The tax authorities (Y1) appealed this to the Supreme Court, leading to a first judgment on April 24, 1956. In this initial ruling, the Supreme Court found the High Court's reasoning insufficient and remanded the case for further examination. The Supreme Court stated that for the State not to be considered a "third party with a legitimate interest" entitled to assert X's lack of registration (a key concept under Civil Code Article 177), the mere fact that X had paid property tax was not enough. The Court stipulated that "special circumstances" (tokudan no jijō) would need to be established. Such circumstances might include, for example, evidence that the tax office director had definitively recognized the property as belonging to X even against X's own initial representations, or had consistently levied taxes on the explicit assumption that X was the owner, thereby creating a strong and justifiable expectation on X's part that the tax authorities would continue to treat him as such.

- Following the remand, the Nagoya High Court reconsidered the case and, on June 28, 1957, once again ruled against X. X then appealed this second High Court decision back to the Supreme Court, arguing that the "special circumstances" required by the Supreme Court's earlier remand judgment did indeed exist.

The Supreme Court's Final Verdict: True Owner Prevails

In its final judgment on March 31, 1960, the Supreme Court overturned the decision of the High Court (post-remand) and ruled decisively in favor of X, the original purchaser. The Court found that the Public Sale Disposition was invalid and ordered the cancellation of Y2's ownership registration.

"Special Circumstances" Established:

The Supreme Court carefully considered the factual record as established by the High Court after the remand. In addition to the initial facts, the Court highlighted several crucial findings:

- X's property tax declaration in 1946 had specifically noted that although the Land was registered in Company A's name, it was, in substance, X's property.

- The Uozu Tax Office Director had, at that time, acknowledged X's acquisition of ownership.

- After purchasing the Land, X had sold a building situated on it to another individual, B, and had leased the Land itself to B. To ensure tax notices concerning the Land were not sent to the registered owner (Company A), X had petitioned the local city office to have the notices delivered to B, who would then pay the local taxes using the rent owed to X. This arrangement was implemented.

- For approximately five years, from X's purchase until the seizure in 1950, no one had challenged X's ownership of the Land.

- Upon learning of the seizure (which was part of the tax delinquency action against Company A), X immediately took steps to assert his rights. He had his ownership formally registered (albeit after the seizure) and submitted an application to Y1 (the Toyama Tax Office Director) to cancel the delinquency disposition against the Land. This application was initially ignored by the tax office and was only formally rejected much later, after X had already initiated his lawsuit.

- The seizure of the Land, rather than Company A's factory machinery, had been instigated by A' (Company A's controller) after A' discovered the Land was still registered in Company A's name.

State Barred from Asserting Lack of Registration:

Considering these detailed facts, particularly X's explicit declaration of substantive ownership, the tax office's initial acknowledgment, X's continuous and undisputed possession and use (including leasing and arranging for tax payments via his tenant), and the circumstances surrounding the seizure, the Supreme Court concluded: "[C]onsidering these facts... there were circumstances where X could strongly and justifiably expect the Land to be treated as his by the competent tax office director." This finding satisfied the "special circumstances" test laid down in the Supreme Court's 1956 remand judgment.

Consequently, the Court held that Y1 (representing the State) was "not a third party with a legitimate interest to assert the lack of registration against X's acquisition of ownership of the Land."

Public Sale Deemed Invalid:

Because the State could not validly assert X's lack of registration to treat the Land as Company A's property for tax delinquency purposes, the entire Public Sale Disposition—including the seizure and the subsequent sale to Y2—was deemed to have "targeted property not belonging to the delinquent taxpayer." As such, the Court declared it "invalid in the sense that they do not produce the effect of having Y2 [the auction purchaser] acquire ownership of the target property."

Unpacking the Decision: Civil Law Meets Public Power

This case is a significant illustration of how Japanese courts apply private law principles, particularly from the Civil Code, to actions taken by administrative bodies.

Civil Code Article 177 and Tax Collection: An Established Link

Article 177 of the Civil Code states that acquisitions or alterations of real rights concerning immovable property cannot be asserted against third parties unless they are registered. The question of whether this article applies to administrative dispositions, especially those involving compulsory measures like tax collection, has seen some evolution.

Historically, an influential "three-part theory" by Dr. Jiro Tanaka suggested that private law (like the Civil Code) was generally inapplicable to "power relationships" between the State and citizens. Some early post-war Supreme Court decisions seemed to reflect this, for example, in cases of agricultural land requisition for establishing owner-farmers, where it was suggested Civil Code Art. 177 did not apply. However, these earlier cases often involved specific statutory schemes with their own distinct policy goals (e.g., focusing on actual land cultivation status rather than just formal registration). Indeed, a 1966 Supreme Court case did apply Article 177 in a land requisition context between the State and a transferee from the original landowner. The current prevailing view is that the applicability of Civil Code Article 177 to legal relationships involving administrative acts must be determined by comprehensively considering the purpose of the specific empowering statute and the nature of the various interests at stake in each case.

In the specific context of tax delinquency dispositions, however, the courts throughout this very lawsuit (from the first instance to the Supreme Court's final decision) consistently acknowledged that Civil Code Article 177 does apply. The Supreme Court's initial 1956 remand judgment explicitly stated that the State's position when seizing a delinquent taxpayer's property is analogous to that of a private seizing creditor in civil execution. The fact that a tax claim is a public law claim does not mean the State should receive less favorable treatment (or be less bound by registration rules) than a private creditor. This "affirmative view" – that Article 177 applies to tax seizures – was already supported by most lower court judgments and academic theories at the time. Arguments against its application sometimes cited the State's power of "self-execution" for tax claims (unlike private creditors who need court orders) or the investigative powers of tax collectors. However, proponents of the affirmative view countered that self-execution is for efficiency and doesn't define whose property can be seized, and that consistent rules are needed for purchasers at public sales.

The "Bad Faith Acquirer" Principle and Public Authorities:

With the applicability of Article 177 established, the core issue in the final 1960 Supreme Court judgment became whether the tax authority (Y1, representing the State) could be considered a "third party" entitled to rely on X's lack of registration. Under Japanese Civil Code jurisprudence, while a third party's mere knowledge (bad faith) of a prior unregistered transaction usually does not prevent them from asserting their registered rights, an exception exists for a "bad faith acquirer acting against principles of good faith" (背信的悪意者 - haishinteki akuisha). Such a person is generally excluded from the protection afforded to third parties by Article 177.

Both Supreme Court judgments in this case (the 1956 remand and the 1960 final decision) proceeded on this established legal principle. The "special circumstances" test laid down in 1956 was essentially a way to determine if the State's actions put it in a position analogous to such a "bad faith acquirer" – someone who, due to their prior dealings and knowledge, could not legitimately claim to be an ordinary third party prejudiced by the lack of registration.

The 1960 final judgment, by meticulously listing the State's awareness of X's substantive ownership and X's consistent actions as the owner, effectively concluded that the State, in these specific circumstances, could not in good faith assert X's failure to register. Legal scholars have praised this decision for holding public authorities to a high standard of good faith, arguably even stronger than that applied to private individuals. The fact that tax collectors possess investigative powers was likely seen as a factor contributing to the assessment of the tax authority's "bad faith" in ignoring X's claims and the readily available information about his ownership.

Grounds for Invalidity of the Public Sale:

The Supreme Court declared the public sale disposition invalid because it targeted property that did not belong to the delinquent taxpayer (Company A) once the State was barred from denying X's ownership. The commentary suggests various legal theories support this finding of invalidity, including the idea that an administrative act targeting an impossible object (property not owned by the debtor) is null, or that tax officials simply lack the authority to transfer ownership from someone other than the delinquent taxpayer through such a sale.

Conclusion: Upholding Good Faith in the Exercise of Public Authority

The 1960 Supreme Court decision in this case stands as a crucial affirmation that even the State's powerful tax collection machinery is subject to fundamental principles of property law and good faith. While timely registration of property rights is paramount under Civil Code Article 177, this ruling demonstrates that the State cannot ignore substantive ownership when it has, through its actions and knowledge, acknowledged that ownership, or where "special circumstances" make it unjust to allow the State to rely on a mere formality. It underscores that public authorities, in exercising their powers, are expected to act consistently and fairly, especially when their actions can profoundly affect citizens' property rights. The judgment remains a testament to the judiciary's role in ensuring that administrative power is wielded in a manner that respects both legal rights and the principles of good faith.