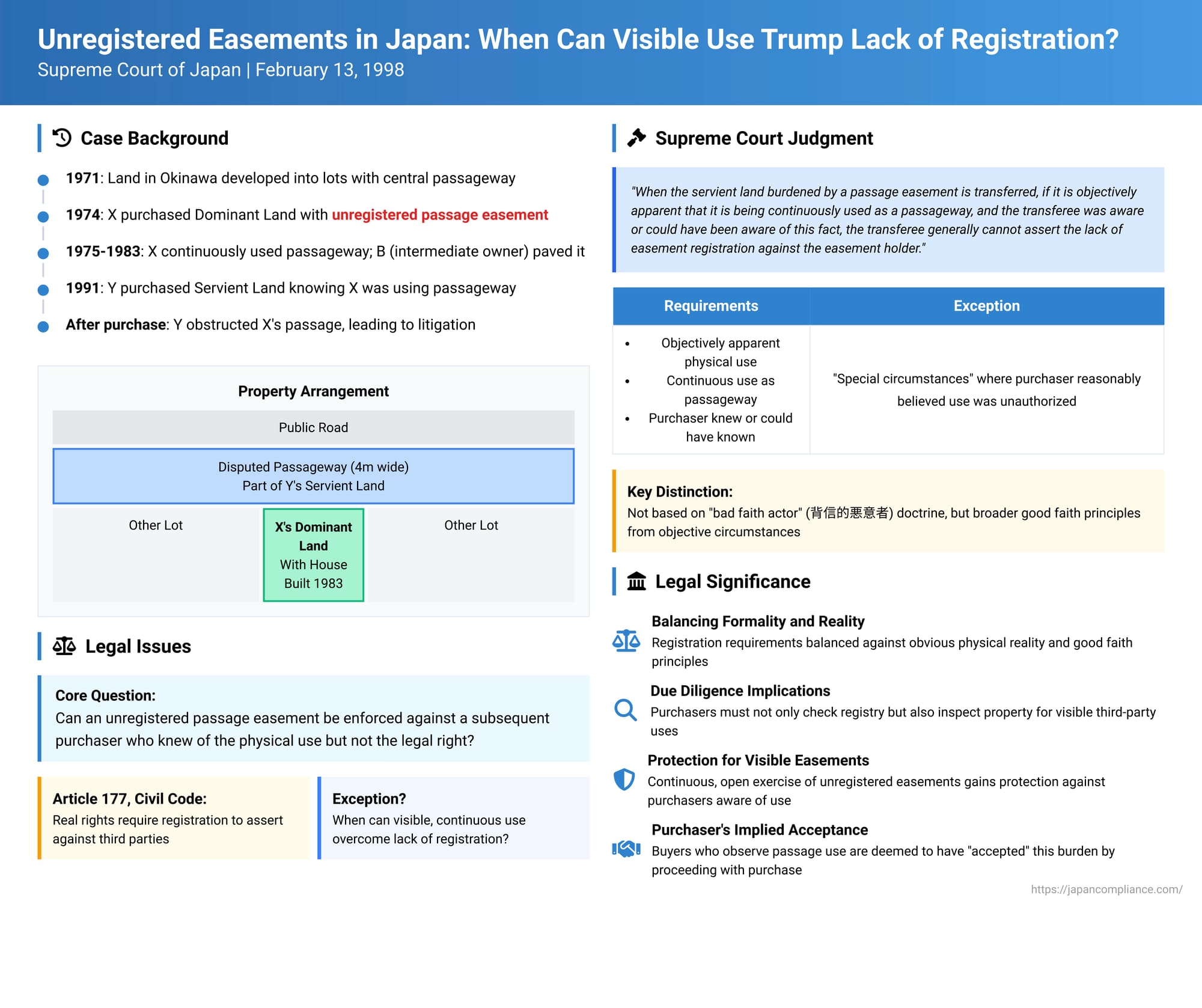

Unregistered Easements in Japan: When Can Visible Use Trump Lack of Registration Against a New Landowner?

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of February 13, 1998 (Heisei 10) (Case No. 966 (O) of 1997 (Heisei 9))

Subject Matter: Claim for Passage Easement Registration Procedures, etc. (通行地役権設定登記手続等請求事件 - Tsūkō Chiekiken Settei Tōki Tetsuzuki tō Seikyū Jiken)

Introduction

This article analyzes a 1998 Japanese Supreme Court judgment that addresses a common yet complex issue in property law: the enforceability of an unregistered passage easement (通行地役権 - tsūkō chiekiken) against a subsequent purchaser of the burdened land (the servient land). Under Article 177 of the Civil Code, real rights concerning immovables generally require registration to be asserted against third parties. However, this case explores an important exception rooted in the principle of good faith, where the objective, visible, and continuous use of land as a passageway, coupled with the purchaser's awareness (or ability to be aware) of such use, can prevent the purchaser from denying the easement despite its lack of registration.

The dispute involved X (appellee/plaintiff), the owner of the dominant land benefiting from the passage easement, and Y (appellant/defendant), the subsequent purchaser of the servient land over which the easement ran.

Factual Background

Around 1971, A, the original owner of a larger tract of land in Yonabaru Town, Okinawa Prefecture, developed it into six residential lots with a central passageway approximately 4 meters wide running north-south, providing access to a public road at its northern end. The west side of this original tract had another, narrower path (less than 1 meter wide) running along its boundary.

In September 1974, A sold one of the central lots on the west side (Lot 3604-8, the "Dominant Land") to X. At that time, A and X implicitly agreed to create a gratuitous and perpetual passage easement over the northern half of the central passageway (the "Disputed Passageway," which was part of the land later acquired by Y) for the benefit of X's Dominant Land. X continuously used the Disputed Passageway as access for his Dominant Land thereafter, but this easement was never registered.

Around January 1975, A sold the remaining eastern and southern lots, along with the entire passageway area (which included the Disputed Passageway), to B. A and B implicitly agreed that B would succeed to A's position as the grantor of X's passage easement. B promptly built his residence on the lots he purchased (excluding the Disputed Passageway area) and paved the Disputed Passageway with asphalt, installing drainage ditches, using it as his own access to the public road. In 1983, X built his house on his Dominant Land, with a parking space on the east side and an entrance facing northeast, and used the Disputed Passageway for vehicle and pedestrian access to the public road. B never objected to X's use.

In July 1991, B sold his land (which included the Disputed Passageway, now part of Lot 3604-5, the "Servient Land") to Y. There was no agreement that Y would succeed to B's position as the grantor of X's passage easement. However, Y, when purchasing the Servient Land, was aware that X was currently using the Disputed Passageway as an access route. Despite this knowledge, Y did not confirm with X whether X had any right of passage. Shortly after acquiring the Servient Land, Y began obstructing X's use of the Disputed Passageway.

X then filed suit, seeking confirmation of his passage easement over the Disputed Passageway and other related reliefs. The appellate court found in favor of X, deeming Y a "bad faith actor with notice amounting to a breach of trust" (背信的悪意者 - haishinteki akuisha) because Y knew or could easily have known of X's rights yet chose to deny them soon after purchase. Y appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, upholding the appellate court's conclusion that X could assert the unregistered passage easement against Y, although it refined the legal reasoning.

The Court laid down the following key principles:

- General Rule for Asserting Unregistered Easements: When the servient land burdened by a passage easement is transferred, if, at the time of transfer:

- it is objectively apparent from the physical condition of the servient land (its location, shape, structure, etc.) that it is being continuously used as a passageway by the owner of the dominant land, AND

- the transferee (purchaser of the servient land) was aware of this fact or could have been aware of it,

then, even if the transferee did not know that a passage easement had actually been established, the transferee generally cannot assert the lack of easement registration against the easement holder, unless "special circumstances" exist.

- Rationale Based on Good Faith and Foreseeability:

- Exclusion from "Third Party" under Article 177: A person who lacks a legitimate interest in asserting the lack of registration is not considered a "third party" under Article 177 of the Civil Code against whom registration is required. This includes not only cases specified in the Real Property Registration Act (e.g., Articles 4 or 5 of the old Act) but also cases where asserting the lack of registration would be contrary to the principle of good faith.

- Purchaser's Implied Acceptance of Burden: If the continuous use of the servient land as a passageway is objectively obvious from its physical state, and the purchaser is aware of (or could easily ascertain) this use, the purchaser can readily infer that the owner of the dominant land likely possesses some form of passage right (such as an easement). The purchaser can also easily inquire with the dominant landowner about the existence and nature of such a right.

- Therefore, even if such a purchaser acquires the servient land without actual knowledge of a formally established easement, they should be considered to have acquired it subject to some burden of passage. For such a purchaser to then assert the lack of easement registration against the easement holder would ordinarily be contrary to the principle of good faith.

- "Special Circumstances" Exception: An exception exists if, for example, the purchaser of the servient land recognized that the use as a passageway was without legal right, and the conduct of the easement holder contributed to this misapprehension. In such special circumstances, asserting the lack of registration might not be contrary to good faith.

- Not Necessarily a "Haishinteki Akuisha" (Bad Faith Actor with Notice Amounting to Breach of Trust):

The Court clarified that this conclusion (that the purchaser cannot assert the lack of registration) is not necessarily based on labeling the purchaser a "haishinteki akuisha." The "haishinteki akuisha" doctrine typically requires a degree of malicious intent or knowledge of the specific prior right that goes beyond what is required here. The current rule is based on the broader principle of good faith derived from the objective circumstances and the purchaser's awareness (or constructive awareness) of the ongoing, visible use. Thus, it is not essential for the purchaser to have known that an easement was specifically established at the time of acquiring the servient land. - Application to the Case:

A passage easement was established (albeit implicitly) for X's Dominant Land over the Disputed Passageway (part of Y's Servient Land). When Y acquired the Servient Land, the continuous use of the Disputed Passageway by X (owner of the Dominant Land) was objectively apparent from its physical condition (location, shape, structure, etc.), and Y was aware of this use. No "special circumstances" that would justify Y denying the easement were found.

Therefore, even if Y did not know that a passage easement had been formally established, Y could not assert the lack of easement registration against X and was not considered a third party with a legitimate interest in doing so.

The Supreme Court found that while the appellate court's labeling of Y as a "haishinteki akuisha" might have been an inappropriate choice of words, its ultimate conclusion—that Y could not assert the lack of registration against X's passage easement—was correct. The appeal was dismissed.

Analysis and Implications

This 1998 Supreme Court judgment is a landmark decision concerning the protection of unregistered but openly exercised passage easements against subsequent purchasers of the servient land.

- Objective Visibility and Purchaser's Awareness are Key: The ruling establishes that the objective, physical evidence of continuous use as a passageway, combined with the purchaser's actual or constructive knowledge of such use, can prevent the purchaser from relying on the lack of easement registration. This emphasizes the importance of physical inspection and due diligence by purchasers of land.

- Good Faith Principle Applied: The decision is grounded in the principle of good faith. If a purchaser buys land that is clearly and continuously being used as a passage by an adjoining landowner, and the purchaser is aware of this (or should be), it is generally considered contrary to good faith for them to later try to extinguish that passage right simply because it wasn't registered. They are deemed to have acquired the land with an expectation of some existing access right burdening it.

- Distinction from "Haishinteki Akuisha": The Court's clarification that this rule does not necessarily depend on the purchaser being a "haishinteki akuisha" (a more stringent category requiring a degree of malicious intent or knowledge of the specific legal right being defeated) is significant. The threshold here is based on the obviousness of the physical use and the purchaser's awareness of that use, rather than knowledge of the legal character of the easement. This makes it somewhat easier for holders of visibly exercised but unregistered easements to protect their rights.

- "Special Circumstances" as a Safeguard: The "special circumstances" exception provides a safety valve. If the easement holder's own conduct misled the purchaser into believing the use was unauthorized or temporary, the purchaser might still be able to assert the lack of registration.

- Impact on Land Transactions: This judgment has important implications for land transactions in Japan:

- For purchasers of land: It highlights the need not only to check the property register but also to conduct a thorough physical inspection of the property and its surroundings to identify any apparent uses by third parties that might indicate unregistered rights like easements. Inquiry with neighbors or users may be necessary.

- For holders of unregistered easements: While registration is always the safest way to protect an easement, this ruling offers a degree of protection if the easement has been continuously, openly, and visibly exercised, and the new owner of the servient land knew or should have known about it.

This decision balances the formal requirement of registration with the realities of land use and the equitable principle of good faith. It recognizes that in certain situations, the open and continuous exercise of a right like a passage easement can create a legitimate expectation of its continued existence, which a subsequent purchaser aware of such use cannot simply ignore based on a technical lack of registration.