Unraveling Linked Deals: Japanese Supreme Court on Rescinding Multiple Contracts When One Fails

Judgment Date: November 12, 1996

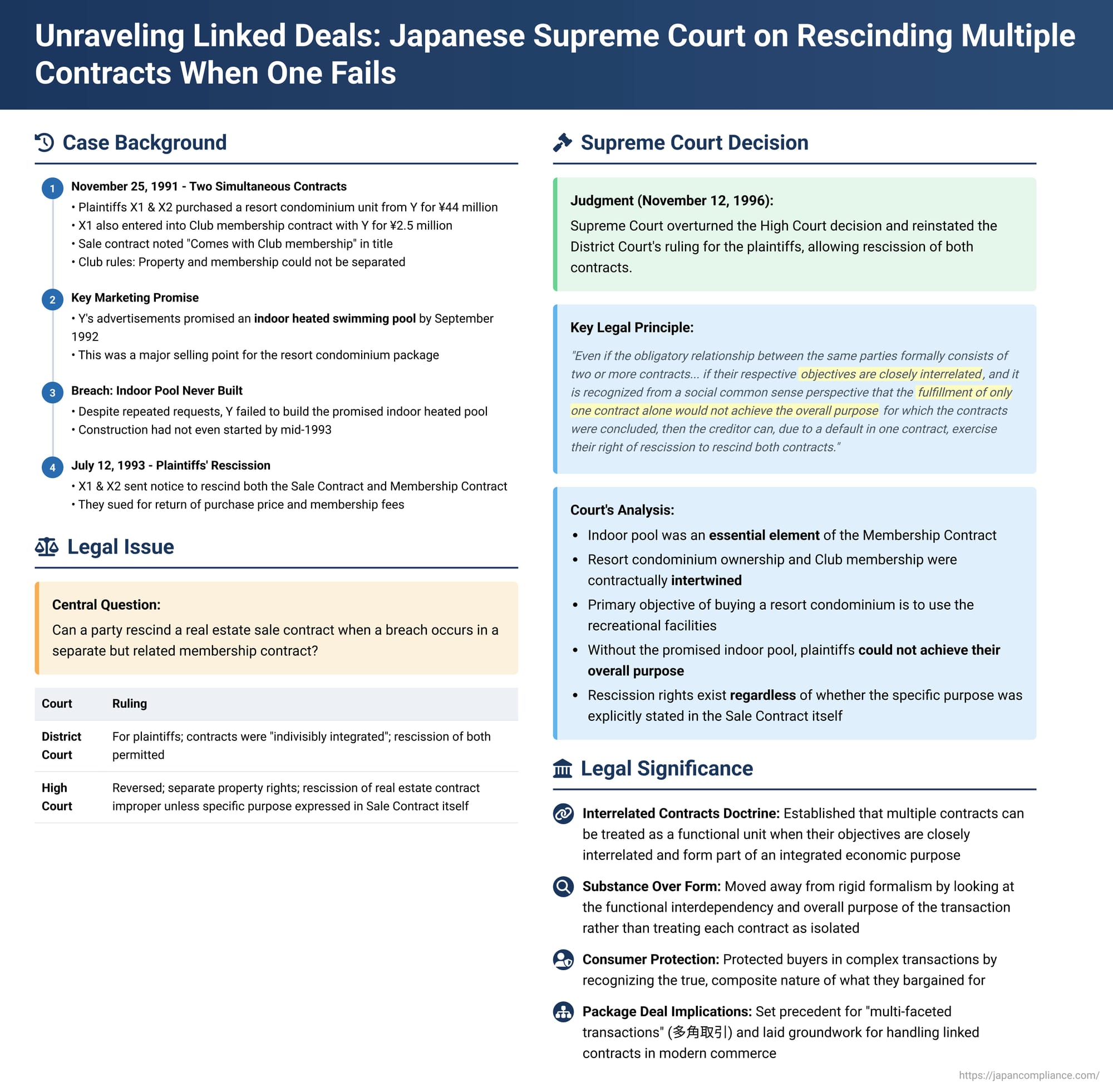

In modern commerce, it's not uncommon for parties to enter into multiple contracts that, while formally separate, are intended to achieve a single, overarching economic or personal objective. A critical legal question arises when one of these linked contracts is breached: can the aggrieved party rescind not only the breached contract but also other related agreements entered into as part of the same overall transaction? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this intricate issue in a significant decision on November 12, 1996 (Heisei 8 (O) No. 1056), concerning a resort condominium purchase tied to a sports club membership.

The Resort Package: A Condominium Unit and a Sports Club Membership

The defendant, Y, was a company engaged in real estate development and sales. It had constructed and was selling units in a resort condominium complex ("the Condominium") and also owned and managed an associated sports facility ("the Club").

The plaintiffs, X1 and X2, jointly purchased a unit in the Condominium ("the Property") from Y on November 25, 1991, for a price of ¥44 million. This agreement will be referred to as the "Sale Contract." They duly paid the required deposit and the balance of the purchase price.

Simultaneously with the Sale Contract, one of the plaintiffs, X1, also entered into a separate agreement with Y to purchase a membership in the Club (the "Membership Contract"). For this, X1 paid a registration fee and a membership deposit totaling ¥2.5 million.

The two contracts were explicitly and implicitly intertwined:

- The Sale Contract document, prepared by Y, bore the notation "Comes with the Club membership" in its title and preamble.

- A special clause within the Sale Contract stipulated that the buyer of the Property would simultaneously become a member of the Club. It also required that any subsequent purchaser of the Property from the original buyer must agree to abide by the Club's rules.

- The Club's internal regulations further cemented this link. They stated that ownership of a unit in the Condominium inherently included membership in the Club, and crucially, that the condominium unit ownership and the Club membership could not be sold or otherwise disposed of separately. If a unit owner transferred their ownership, their Club membership would automatically terminate, with the new unit owner being eligible to apply for Club membership subject to Y's approval.

A key factor in the plaintiffs' decision was Y's marketing. In newspaper advertisements, brochures, and other promotional materials for the Condominium units and Club memberships, Y detailed the Club's facilities. These included existing amenities like tennis courts, an outdoor swimming pool, a sauna, and a restaurant. Importantly, Y's materials also explicitly stated that an indoor heated swimming pool and a jacuzzi were scheduled for completion by the end of September 1992.

The Unfulfilled Promise and the Buyers' Decision to Rescind

Despite the plaintiffs' repeated requests, Y failed to construct the promised indoor heated pool. In fact, construction had not even commenced. As a result of this failure and the significant delay, X1 and X2, by a written notice that reached Y on July 12, 1993, declared their intention to rescind both the Sale Contract for the Property and the Membership Contract for the Club.

Subsequently, X1 and X2 filed a lawsuit. They each sought damages amounting to ¥23.9 million in relation to the Sale Contract. This figure represented half of the original purchase price (¥44 million), less ¥600,000 that Y had previously paid them in acknowledgment of the delay, plus an amount equivalent to half of the agreed-upon penalty (which was equal to the initial deposit) for seller's breach. Additionally, X1 sought the return of the ¥2.5 million he had paid for the Club membership registration fee and deposit.

Diverging Paths in the Lower Courts

The case took different turns in the lower courts:

- First Instance (Osaka District Court): The District Court found in favor of the plaintiffs. It viewed the Sale Contract and the Membership Contract as being "indivisibly integrated" (不可分的に一体化したもの - fukabunteki ni ittaika shita mono). Based on this integrated view, the court upheld the plaintiffs' rescission of both contracts and granted their claims for damages and return of payments in full.

- Second Instance (Osaka High Court): The High Court reversed the District Court's decision. It reasoned that the Property (the condominium unit) and the Club membership were legally distinct and independent property rights. Therefore, they could not be considered a single, unified object of the Sale Contract. The High Court acknowledged that in cases where a real estate sale contract is accompanied by a membership purchase contract, a breach of the membership contract could justify rescinding the real estate contract. However, it set a condition: this would only be possible if the fulfillment of the membership contract obligations was essential to achieving the main purpose of the real estate sale, and this essentiality was explicitly expressed or indicated in the terms of the real estate sale contract itself. The High Court found that while the availability of the indoor pool might have been an important motive for the plaintiffs, this motive was not sufficiently expressed within the four corners of the Sale Contract. Consequently, it ruled that even if Y had breached the Membership Contract by failing to complete the pool, X1 and X2 were not entitled to rescind the Sale Contract. Their claims were dismissed.

Aggrieved by this outcome, X1 and X2 appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other things, that the use of the indoor pool facility was indeed part of the agreed content of the Sale Contract.

The Supreme Court's Unified Approach: Interrelated Objectives and Frustration of Overall Purpose

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and reinstated the judgment of the First Instance court, thereby ruling in favor of the plaintiffs.

The Supreme Court's reasoning proceeded as follows:

- Indoor Pool as an Essential Element of the Membership Contract: The Court first established that the indoor heated pool was not a trivial or ancillary feature of the Club. Given that it was advertised as a major facility intended for year-round use (unlike the existing outdoor pool) and was scheduled for completion by September 1992 (or a reasonable time thereafter), the ability to use this facility constituted an important substantive right for Club members. Therefore, Y's failure to complete the indoor pool within the stipulated timeframe was not merely a minor breach but a failure concerning an essential element (要素たる債務 - yōso taru saimu) of the Membership Contract.

- Close Interrelation of the Sale and Membership Contracts: The Supreme Court highlighted the contractual provisions that inextricably linked the ownership of a Condominium unit with membership in the Club. The rules mandating concurrent ownership and membership, and prohibiting their separate disposal, demonstrated that Y itself did not permit these two rights to be held by different parties. Buyers like X1 and X2 entered into these agreements accepting this integrated structure.

- The Core Legal Principle for Rescinding Linked Contracts: The Court then articulated a general principle for situations where multiple, formally distinct contracts exist between the same parties:

"Even if the obligatory relationship between the same parties formally consists of two or more contracts, such as Contract A and Contract B, if their respective objectives are closely interrelated (目的とするところが相互に密接に関連付けられていて - mokuteki to suru tokoro ga sōgo ni missetsu ni kanren tsukerarete ite), and it is recognized from a social common sense perspective that the fulfillment of only Contract A or Contract B alone would not achieve the overall purpose for which the contracts were concluded (契約を締結した目的が全体としては達成されない - keiyaku o teiketsu shita mokuteki ga zentai to shite wa tassei sarenai), then it is appropriate to interpret that the creditor can, due to a default in Contract A, exercise their statutory right of rescission to rescind Contract B together with Contract A." - Application to the Facts of the Case: Applying this principle, the Supreme Court found:

- The Property was a unit in a resort condominium, a type of property where a primary objective for purchasers is typically the use of associated sports and recreational facilities, including, in this instance, the promised indoor pool.

- The facts indicated that X1 and X2 had purchased the Property with precisely this objective in mind—to enjoy it as a resort condominium with comprehensive amenities.

- Y's failure to complete the indoor pool, being a breach of an essential element of the Membership Contract, meant that X1 and X2 could not achieve the overall purpose for which they had entered into the Sale Contract for the resort condominium unit.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that X1 and X2 were entitled to rescind the Sale Contract pursuant to Article 541 of the Civil Code (which governs rescission for delay in performance), based on Y's breach of its obligations under the Membership Contract. Crucially, this right to rescind the Sale Contract existed regardless of whether the specific purpose of using the indoor pool had been explicitly stated or formally incorporated into the text of the Sale Contract document itself. The nature of the resort condominium, the marketing, and the intertwined contractual structure made the overall purpose clear.

Analyzing the "Interrelated Contracts" Doctrine

This Supreme Court decision provides a pragmatic and purposive approach to situations where multiple, formally separate agreements between the same two parties are, in substance, part of a single, unified transaction or package deal. It recognizes that parties often enter into such linked contracts with an overall objective in mind, and the failure of a critical component can render the entire arrangement pointless for the aggrieved party.

Key aspects of the Court's doctrine include:

- Focus on Interrelated Objectives: The primary test is whether the objectives of the individual contracts are "closely interrelated."

- Achievement of Overall Purpose: The critical question is whether, from a "social common sense" perspective, the fulfillment of only one of the contracts, in the absence of the other (or due to a breach in the other), would fail to achieve the overall purpose for which the parties entered into the set of agreements.

- Independence from Expressed Motive in Each Contract: Significantly, the Court moved away from the High Court's reliance on whether the specific purpose or motive (e.g., using the indoor pool) was explicitly expressed within the four corners of the contract being rescinded (the Sale Contract). If the interrelation and the overall purpose are clear from the entire context of the transaction and the nature of the agreements, that is sufficient.

This ruling can be seen as a foundational example for addressing more complex "multi-faceted transactions" (多角取引 - takaku torihiki), which might involve multiple parties and numerous contracts. While this case involved only two parties and two main contracts, the principle of looking at the functional interdependency and overall purpose has broader relevance. Legal commentators note that this decision implicitly values the actual, combined intent of the parties over a rigidly formalistic separation of contracts, especially when one contract is clearly ancillary or essential to the utility of another. The Court effectively recognized that the "resort condominium with full club facilities (including an indoor pool)" was the true, composite subject matter the plaintiffs bargained for.

Implications for Contracting Parties

The judgment carries important lessons for parties structuring complex deals involving multiple agreements:

- Package Deals: When products or services are sold as a "package," where the value or utility of one component is intrinsically linked to another, a failure to deliver a critical part of that package can risk the unraveling of the entire set of agreements.

- Clarity of Essential Terms: While the Supreme Court did not require the specific purpose to be stated in every contract, clearly defining essential components and their interdependencies in the contractual documentation can help avoid disputes.

- Seller/Provider Responsibility: Sellers or providers offering linked products or services must be mindful that a default in one area can have cascading consequences for other related agreements if that default frustrates the buyer's overarching purpose.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1996 decision in this resort condominium case provides a vital precedent for the rescission of linked contracts between the same parties. By establishing that a breach in one contract can justify the rescission of another if their objectives are closely interrelated and the overall purpose of the transaction cannot be achieved without the fulfillment of both, the Court championed a substance-over-form approach. This ruling underscores the importance of considering the holistic intent and purpose behind multiple agreements when a critical component fails, ensuring that parties are not unfairly bound to a transaction that no longer serves its intended, mutually understood objective.