Unraveling Linked Deals: Japanese Supreme Court on Rescinding a Condo Sale Due to Breach in a Separate Membership Contract

Date of Judgment: November 12, 1996

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, 1996 (O) No. 1056 – Claim for Damages, etc.

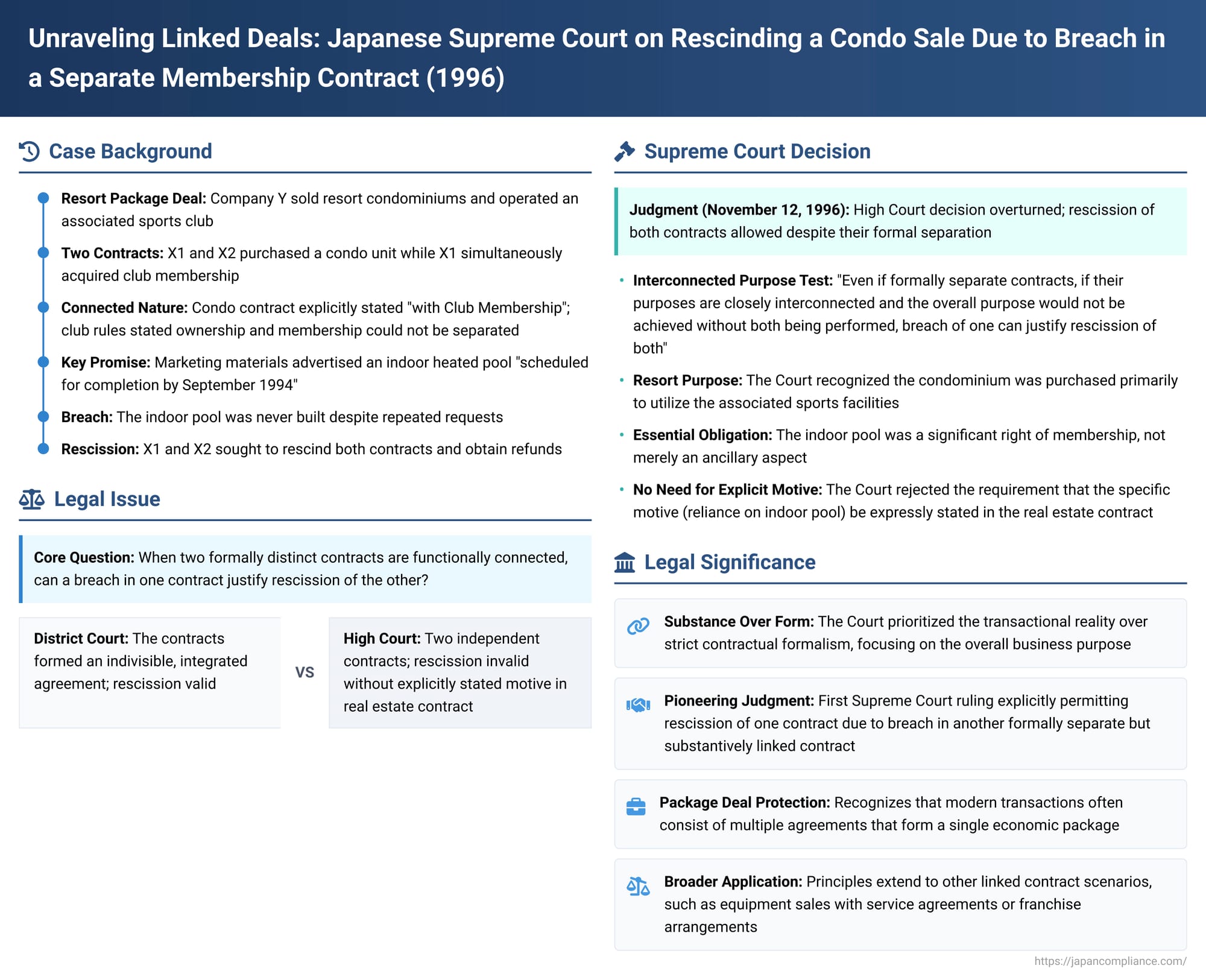

Modern commercial transactions often involve multiple agreements that, while formally distinct, are intrinsically linked to achieve a single overarching economic purpose. A crucial question arises when one of these linked contracts is breached: can the aggrieved party unravel not just the breached agreement but also other related contracts that were part of the same package deal? A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on November 12, 1996, addressed this very issue in the context of a resort condominium purchase tied to a sports club membership, establishing an important precedent for how Japanese law views the interconnectedness of such agreements.

The Resort Package: A Condominium, a Club Membership, and a Promised Pool

The case involved Company Y, a developer that had constructed and was selling units in a resort condominium complex (referred to as "the Condominium"). Company Y also owned and managed an associated sports facility, "the Club". Two individuals, X1 and X2 (the plaintiffs), entered into an agreement with Company Y to purchase a unit in the Condominium (the "Real Estate Sale Contract") and duly paid the purchase price. Simultaneously with this property purchase, X1 entered into a separate contract with Company Y to acquire a membership in the Club (the "Membership Contract"), paying the requisite registration fees and membership deposit.

The interconnectedness of these two agreements was evident from several factors:

- The Real Estate Sale Contract documents explicitly bore titles and preambles stating it was "with Club Membership".

- A special condition within the Real Estate Sale Contract stipulated that the buyer of the condominium unit would automatically become a member of the Club upon purchasing the property.

- Conversely, the Club's official rules stated that ownership of a unit in the Condominium was inherently tied to Club membership and that the two could not be disposed of separately. If a unit owner transferred their ownership of the condominium, their Club membership would automatically terminate.

- In its marketing efforts, Company Y's newspaper advertisements and brochures prominently featured the Club's facilities. These materials listed existing amenities such as tennis courts, an outdoor pool, a sauna, and a restaurant. Crucially, they also expressly stated that an indoor heated swimming pool and a jacuzzi were "scheduled for completion" by September 1994.

After purchasing the unit and membership, X1 and X2 repeatedly urged Company Y to proceed with the construction of the promised indoor pool. However, construction never even commenced. Faced with this ongoing failure, X1 and X2 notified Company Y of their intention to rescind not only the Membership Contract (due to the non-delivery of the promised pool) but also the Real Estate Sale Contract for the condominium unit. They subsequently filed a lawsuit seeking the return of their payments and other damages.

Diverging Paths in the Lower Courts

The case took different turns in the lower courts:

- The District Court found in favor of X1 and X2. It viewed the Real Estate Sale Contract and the Membership Contract as being so closely intertwined that they formed an indivisible, integrated agreement. Based on this, the court held that the rescission of the Real Estate Sale Contract was valid due to the breach related to the Club's facilities and ordered the requested refunds.

- The High Court, however, reversed the District Court's decision. It held that the condominium unit (real estate) and the Club membership were, in terms of property rights, separate and distinct. Therefore, they constituted two independent contracts, not a single integrated one. The High Court acknowledged that a breach of obligations under the Membership Contract (like failing to build the pool) could potentially justify the rescission of the Real Estate Sale Contract if the fulfillment of those membership obligations was essential to achieving the primary purpose for which the Real Estate Sale Contract was concluded. However, it imposed a critical condition: this "motive" or purpose (i.e., the importance of the indoor pool to the buyers) had to be explicitly expressed in the Real Estate Sale Contract itself. Since the High Court found that the buyers' crucial motivation regarding the indoor pool was not so expressed in the property sale agreement, it ruled that the Real Estate Sale Contract could not be rescinded, even if the Membership Contract was breached. Consequently, X1 and X2's claims were dismissed.

X1 and X2 appealed the High Court's unfavorable decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: Interconnectedness Over Formality

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of November 12, 1996, overturned the High Court's decision and ultimately ruled in favor of X1 and X2, effectively upholding the District Court's initial judgment that allowed rescission of both contracts.

The Supreme Court articulated a pivotal legal principle:

"Even if a debtor-creditor relationship between the same parties formally consists of two or more contracts, such as Contract A and Contract B, if their respective purposes are closely interconnected and it is recognized that, according to social custom (social common sense), the purpose for which the contracts were concluded as a whole would not be achieved if only either Contract A or Contract B is performed, then a breach of an obligation under Contract A can justify the creditor's exercise of a statutory right of rescission to rescind Contract B together with Contract A."

Applying this principle to the facts of the case, the Supreme Court reasoned:

- The property in question was a "resort condominium," the purchase of which was primarily aimed at utilizing the associated sports facilities, including the promised indoor heated pool. The Court found that the circumstances indicated X1 and X2 had purchased the property with this specific type of utility in mind.

- The failure by Company Y to complete the indoor pool by the scheduled time (or a reasonable period thereafter) constituted a delay in performing an essential obligation under the Membership Contract. The Court emphasized that access to this all-season indoor pool was a significant right of the members and not merely an ancillary or minor aspect of the membership.

- This breach of an essential element of the Membership Contract meant that the overall purpose for which X1 and X2 had entered into the Real Estate Sale Contract could no longer be achieved.

- Crucially, the Supreme Court held that under these circumstances, X1 and X2 could rescind the Real Estate Sale Contract based on the delay in fulfilling the Membership Contract obligations (specifically, the completion of the indoor pool), pursuant to Article 541 of the Japanese Civil Code (which governs rescission due to delay in performance). This was permissible regardless of whether their specific purpose or motive concerning the indoor pool had been explicitly stated in the Real Estate Sale Contract itself. This directly contradicted the High Court's more restrictive view.

Deep Dive: The Concept of Linked Contracts and Rescission

This Supreme Court decision was a significant development in Japanese contract law, particularly concerning linked or composite contracts.

- Pioneering Judgment: The commentary accompanying the case highlights that this was one of the first Supreme Court rulings to explicitly permit the rescission of one contract due to a breach in another formally separate but substantively linked contract between the same two parties.

- The "Number of Contracts" Question: The District Court had treated the transaction as effectively a single, indivisible "mixed contract." The High Court and the Supreme Court, however, proceeded on the basis that there were formally two distinct contracts. The commentary suggests that while determining the number of contracts can be a complex preliminary issue, the Supreme Court's approach in this case implies that if the purposes are deeply interconnected, the formal count of contracts becomes less decisive for the outcome of rescission rights. Factors like the contracts pertaining to different types of property (real estate vs. membership rights) and each having its own distinct consideration likely supported the view of there being two contracts. However, if rescission of one can flow from the breach of another due to their linked objectives, the practical impact is similar to treating them as a unified whole for rescission purposes.

- Interrelatedness of Purpose as the Key: The Supreme Court's test hinges on whether the "purpose for which the contracts were concluded as a whole would not be achieved" if one part of the linked deal fails. This looks beyond the letter of each isolated contract to the overall transactional intent.

- No Need for Explicit "Motive" Declaration: A critical aspect of the ruling was the rejection of the High Court's requirement that the specific motive (reliance on the indoor pool) be expressly stated in the Real Estate Sale Contract. The Supreme Court found that the nature of the property as a "resort condominium" inherently implied that the availability of advertised major amenities like an indoor pool was a fundamental part of the bargain. The commentary suggests that this shared purpose was considered to be incorporated into the overall contractual understanding, even if not reiterated in every document.

Legal Framework and Broader Implications

The Supreme Court did not explicitly ground its decision in a specific overarching theory like a "framework agreement" (waku keiyaku) that encompasses sub-agreements, or directly invoke doctrines such as "frustration of purpose" or "change of circumstances" (jijō henkō no gensoku), though these are concepts discussed in legal scholarship for analyzing such linked contract scenarios. Instead, it focused on the practical interdependency of the contracts and the frustration of the overall contractual objective, justifying rescission under the existing statutory provision for breach by delay.

This ruling has significant implications:

- It provides a basis for parties to seek broader remedies when a component of a multi-contract package deal fails, reflecting the economic reality that such deals are often entered into as a whole.

- It places importance on the substance of the transaction and the parties' overall objectives rather than adhering strictly to the formal separation of agreements.

- The principles from this case could potentially extend to other types of linked contracts, such as sales of equipment tied to mandatory service agreements, or franchise agreements that involve multiple related contracts.

- The commentary notes that subsequent lower court decisions have explored similar issues in multi-party contexts, such as condominiums sold with essential care services provided by a separate (though often related) company, or contracts in the entertainment industry linking an artist's management contract with a recording contract. While this Supreme Court case involved only two parties, it laid foundational thinking for how Japanese courts might approach the "domino effect" of breaches in more complex, multi-party linked transactions.

Conclusion: Prioritizing Transactional Reality Over Strict Formalism

The Supreme Court's 1996 decision in the resort condominium case represents a vital affirmation that Japanese contract law can look beyond the formal structure of agreements to their substantive interconnectedness. By allowing the rescission of a real estate sale contract due to the seller's failure to fulfill a promise related to an associated club membership, the Court prioritized the achievement of the overall purpose for which the linked contracts were entered into. This ruling acknowledges the practical reality that many modern transactions are not isolated events but rather packages of rights and obligations, and that a failure in one critical component can render the entire package valueless to the aggrieved party. It signals that sellers who market integrated lifestyle or service packages bear a responsibility to deliver on all essential components of that package, or risk the unraveling of the entire deal.