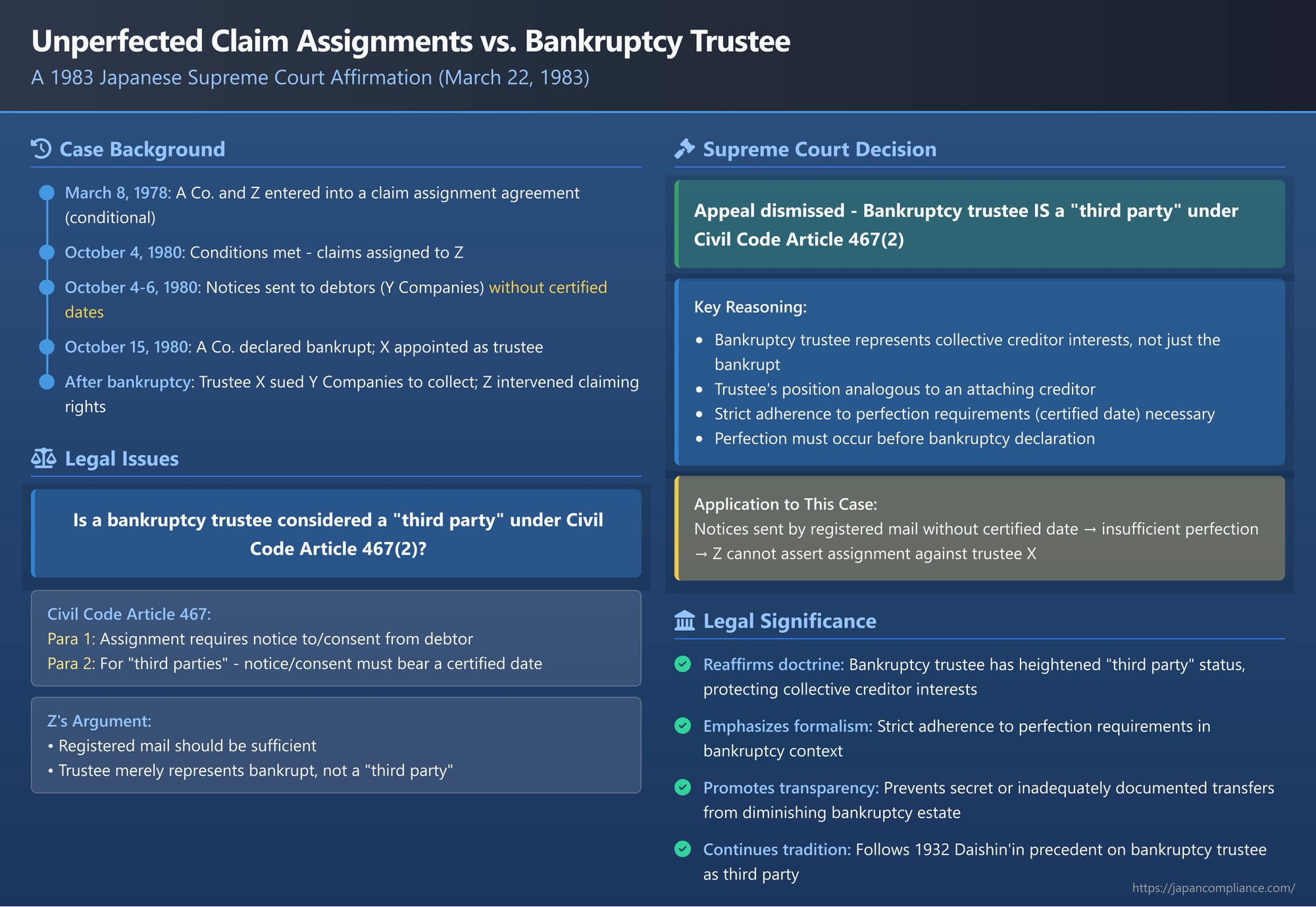

Unperfected Claim Assignments vs. Bankruptcy Trustee: A 1983 Japanese Supreme Court Affirmation

On March 22, 1983, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a judgment that reaffirmed a critical principle in Japanese insolvency law: an assignee of a monetary claim must strictly adhere to perfection requirements, including obtaining a notice with a "certified date," before the assignor's bankruptcy if they wish to assert that assignment against the assignor's bankruptcy trustee. This decision underscores the robust position of the bankruptcy trustee as a representative of the collective creditor interest, akin to that of an attaching creditor.

Factual Background: Claim Assignment and Subsequent Bankruptcy

The case involved A Co., which had entered into a claim assignment agreement with Z on March 8, 1978. This agreement stipulated that A Co.'s then-existing and future accounts receivable would be assigned to Z upon the occurrence of certain conditions precedent, such as A Co. ceasing its operations. These conditions were fulfilled on October 4, 1980, at which point the assignment of A Co.'s accounts receivable—owed by several debtor companies (collectively, Y Companies)—to Z became effective.

Around the same day, October 4, 1980, notices of this claim assignment were sent in A Co.'s name to the Y Companies. These notices, stating that their respective debts to A Co. had been assigned to Z, were dispatched by registered mail and reached the Y Companies around October 6, 1980. However, a crucial detail was that these notices lacked a "certified date" (確定日付 - kakutei hizuke), a formal authentication of the date of a document.

Shortly thereafter, on October 15, 1980, A Co. was declared bankrupt, and X was appointed as its bankruptcy trustee. Trustee X subsequently initiated lawsuits against the Y Companies to collect the accounts receivable for the benefit of A Co.'s bankruptcy estate. Z intervened in these proceedings, asserting that the claims had been validly assigned to Z prior to the bankruptcy and therefore should be paid to Z, not to the trustee.

The Osaka High Court, affirming the first instance court, ruled against Z. It held that in the event of a pre-bankruptcy assignment of claims by the bankrupt, the bankruptcy trustee stands in the same position as an attaching creditor. Consequently, the trustee is considered a "third party" under Article 467, paragraph 2, of the Civil Code. This provision required that, for a claim assignment to be effective against such third parties, the notice of assignment (or the debtor's consent) must bear a certified date. Since the notices sent by registered mail in this case lacked such a certified date obtained before A Co.'s bankruptcy declaration, Z could not assert the assignment against trustee X. Z then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Framework: Perfecting Claim Assignments Against Third Parties

The legal heart of this case lies in Article 467 of the Japanese Civil Code (as it existed at the time, prior to later reforms which modernized terminology but maintained core principles regarding assignment perfection).

- Article 467, paragraph 1, stipulated that the assignment of a nominative claim (a claim against a specific person) could not be set up against the debtor of that claim or other third parties unless the assignor gave notice to the debtor, or the debtor consented to the assignment.

- Article 467, paragraph 2, added a more stringent requirement for asserting the assignment against third parties other than the debtor of the assigned claim. For these third parties, the notice or consent had to be made by an instrument bearing a "certified date."

A "certified date" is a formal stamp or notation by a notary public or certain other public offices on a private document, which provides indisputable evidence that the document existed on that particular date. This requirement was intended to prevent fraudulent backdating of assignments and to provide clear priority rules when multiple parties claimed rights to the same claim.

The critical question before the Supreme Court was whether the bankruptcy trustee of the assignor (A Co.) qualified as a "third party other than the debtor" under Article 467, paragraph 2, against whom this higher standard of perfection (a notice with a certified date) was necessary.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Trustee Protected as a Third Party

The Supreme Court dismissed Z's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's judgment and reaffirming the necessity for strict perfection of claim assignments against a bankruptcy trustee.

The Court unequivocally ruled that: An assignee of a nominative claim, in a situation where the assignor has been declared bankrupt, cannot assert the assignment of that claim against the bankruptcy trustee unless the assignment was perfected in accordance with the requirements of Civil Code Article 467, paragraph 2 (i.e., through a notice to, or consent from, the debtor of the assigned claim, documented by an instrument bearing a certified date) before the assignor's bankruptcy declaration.

Applying this rule to the established facts, since the notices of assignment sent to the Y Companies, although dispatched by registered mail, lacked a certified date obtained prior to A Co.'s bankruptcy declaration on October 15, 1980, Z could not validly assert the assignment against trustee X.

The Supreme Court also addressed and rejected Z's secondary arguments that the notices should be deemed to have acquired a certified date through other means (such as being referenced in subsequent documents that did have a certified date, or through the registered mail receipts themselves). The Court maintained a strict interpretation of how a document acquires a certified date, finding that Z's evidence did not meet the statutory requirements. This underscored the formality and precision demanded for such perfection measures.

Rationale: Why the Bankruptcy Trustee is a "Third Party" under Article 467(2)

While the 1983 judgment itself did not extensively detail the underlying rationale for treating the trustee as a third party, it affirmed a legal principle well-established since a 1932 Daishin'in (the predecessor to the Supreme Court) decision. The traditional reasoning is as follows:

- Bankruptcy as Collective Execution: Bankruptcy proceedings are fundamentally a form of collective execution, aiming to gather all of the debtor's (bankrupt's) executable assets for equitable distribution among all creditors.

- Trustee Represents Creditors' Collective Interest: The bankruptcy trustee acts as a representative of this collective body of creditors. The assets that form the bankruptcy estate are those that individual creditors could have, in principle, sought to attach through individual execution proceedings had bankruptcy not intervened.

- Attaching Creditors as "Third Parties": Under Japanese law, an individual creditor who attaches a claim is generally considered a "third party" for the purposes of Article 467, paragraph 2. Such an attaching creditor can typically prevail over an assignee of that same claim if the assignee has not perfected the assignment with a certified date notice prior to the attachment.

- Trustee's Equivalent Status: Therefore, the bankruptcy trustee, standing in the shoes of the entire creditor body and effectuating a comprehensive, collective "attachment" of the assignor's assets, is accorded the same status as an individual attaching creditor. This means the trustee can defeat an assignment that was not properly perfected against third parties before the bankruptcy commencement.

This rationale ensures that the bankruptcy estate is not diminished by pre-bankruptcy assignments that were not made fully transparent and legally robust through the certified date mechanism, thereby protecting the pool of assets available for all creditors.

Broader Implications for "Third-Party Status" of the Trustee

The principle that the bankruptcy trustee can assert the rights of a "third party" for perfection purposes is a cornerstone of Japanese insolvency law and is not confined to the assignment of claims. It extends, for example, to transactions involving real property, where an unperfected transfer of ownership or the creation of an unperfected mortgage by the bankrupt before bankruptcy generally cannot be asserted against the trustee (in line with Civil Code Article 177, which governs perfection of real property rights).

The underlying policy is to ensure fairness and predictability in the administration of the bankruptcy estate. By upholding perfection requirements, the law aims to protect the collective body of creditors from "secret" or inadequately documented pre-bankruptcy dispositions of the debtor's assets. The critical moment by which such perfection must generally be completed is the time of the bankruptcy commencement order (referred to as "bankruptcy declaration" under the old law).

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 1983 decision in this case robustly reaffirmed a long-standing doctrine essential for the orderly administration of bankrupt estates in Japan. By requiring assignees of nominative claims to have completed perfection via a notice or consent bearing a certified date before the assignor's bankruptcy, the Court underscored the trustee's role as a protector of the collective creditor interest. This consistent stance ensures that only properly publicized and legally certain pre-bankruptcy transactions can diminish the assets available for general distribution, thereby promoting fairness and transparency in the insolvency process. The decision reinforces the idea that the bankruptcy trustee is not merely a successor to the bankrupt but stands in a distinct position, analogous to that of an attaching creditor, for the purpose of challenging unperfected rights.