Stealth Marketing Ban in Japan: New Disclosure Rules & Compliance Playbook (2025)

TL;DR

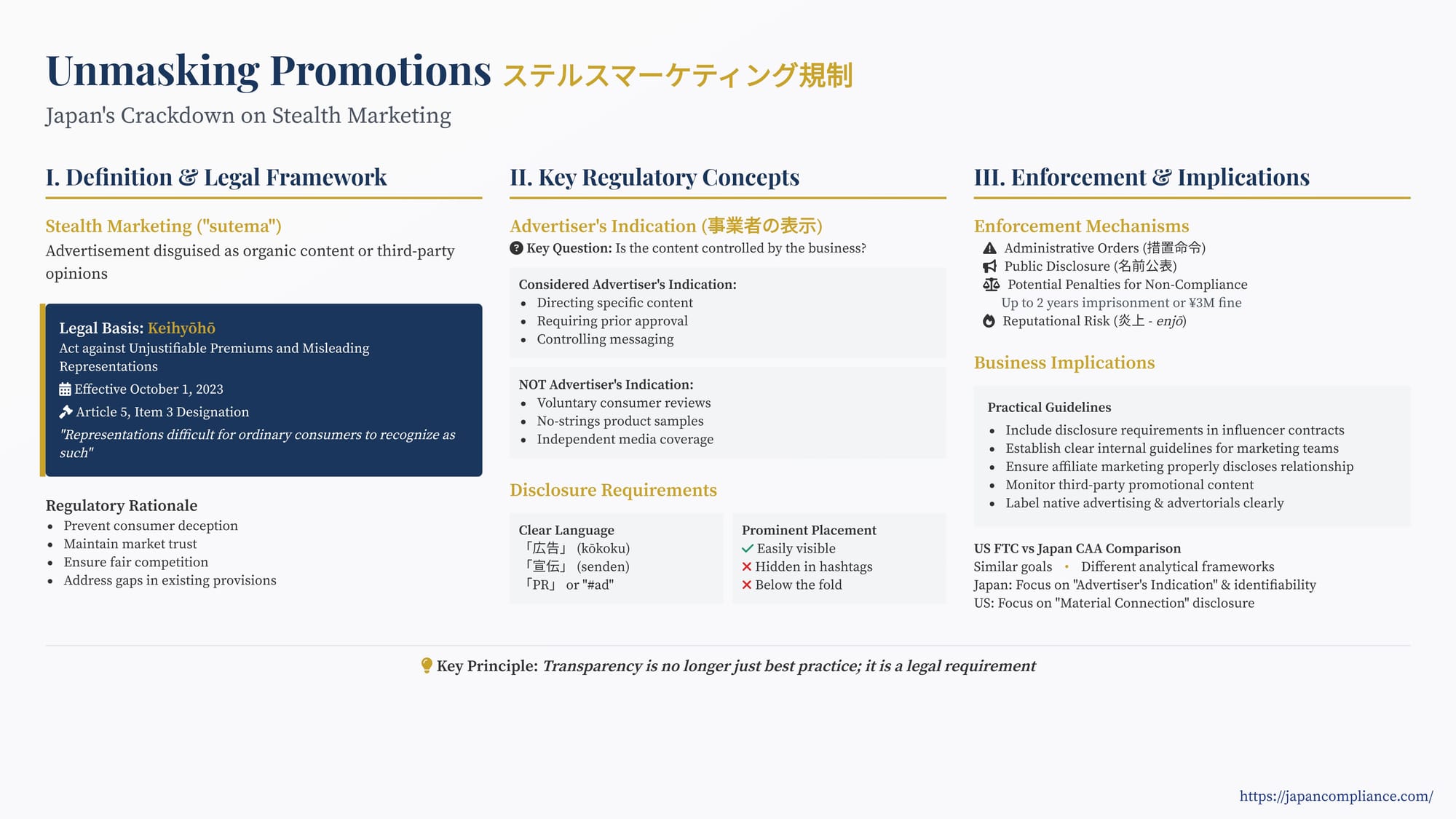

Since October 2023 Japan outlaws undisclosed “stealth marketing” across all media. Any promotion whose content is influenced by the advertiser must be clearly labelled (#広告, #PR, #ad, etc.). Violators face Consumer Affairs Agency orders and public shaming, so brands, influencers and agencies need airtight disclosure policies and contracts.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Rise of "Sutema" and New Regulations

- Background and Rationale: Why Regulate Stealth Marketing Now?

- What Is Regulated? The Core Prohibition and “Advertiser’s Indication”

- Scope of Application: All Media Covered

- Disclosure Requirements: Ensuring Recognizability

- Enforcement and Penalties: Orders and Reputational Risk

- Practical Implications for Businesses

- Comparison with US FTC Guidelines

- Conclusion: Transparency as the New Standard

Introduction: The Rise of "Sutema" and New Regulations

In the dynamic world of digital advertising and social media influence, transparency has become a critical issue globally. Japan is no exception. The practice known as "stealth marketing" – commonly abbreviated as sutema (ステマ) – where advertisements or promotional content are presented in a way that masks their commercial nature, has drawn increasing scrutiny. Consumers often rely on seemingly organic reviews, endorsements, or recommendations from third parties, whether influencers, fellow users, or even media outlets. When these recommendations are actually paid promotions disguised as unbiased opinions, it can mislead consumers and distort fair market competition.

Recognizing these concerns, Japan's Consumer Affairs Agency (CAA, 消費者庁 - Shōhisha-chō) took a significant step. Effective October 1, 2023, stealth marketing became explicitly prohibited under the Act against Unjustifiable Premiums and Misleading Representations (景品表示法 - Keihin Hyōji Hō, often shortened to Keihyōhō). This move wasn't the creation of entirely new legislation but rather the designation of stealth marketing as a specific type of misleading representation under an existing law (Article 5, Item 3). This designation, accompanied by operational guidelines, signals a clear commitment to ensuring consumers can distinguish between genuine editorial or user content and paid advertising. For foreign businesses marketing products or services to Japanese consumers, understanding the nuances of this regulation is now essential for compliance.

Background and Rationale: Why Regulate Stealth Marketing Now?

While the concept of undisclosed paid endorsements isn't new, the proliferation of online platforms, social media, and influencer marketing dramatically amplified the scale and impact of stealth marketing. Several factors contributed to the timing of Japan's regulatory action:

- Consumer Deception: The core problem is deception. Consumers value authenticity. An endorsement perceived as genuine carries more weight than an obvious advertisement. Stealth marketing exploits this by borrowing the credibility of a third party (influencer, reviewer, seemingly ordinary user) to promote a product or service, potentially leading consumers to make purchasing decisions based on biased or incomplete information.

- Erosion of Trust: Widespread sutema erodes trust not only in specific influencers or platforms but in the advertising ecosystem as a whole. When consumers suspect hidden motives behind recommendations, genuine reviews and legitimate advertising both suffer. High-profile "flaming incidents" (enjō, 炎上), where undisclosed promotions were exposed and caused public backlash, highlighted the reputational risks involved.

- Fair Competition: Stealth marketing can create an uneven playing field. Businesses engaging in transparent advertising may be disadvantaged compared to competitors using deceptive, undisclosed promotions that might appear more persuasive to unwary consumers.

- Rise of Influencer and UGC Marketing: The exponential growth of social media platforms and the creator economy made it easier and more common for businesses to engage third parties for promotion. While many platforms and reputable advertisers developed self-regulatory guidelines, the lack of clear legal prohibition created ambiguity and allowed less scrupulous actors to flourish.

- Existing Legal Gaps: While the Keihyōhō already prohibited overtly false or misleading claims about product quality (Article 5, Item 1 - 優良誤認, yūryō gonin) or price/terms (Article 5, Item 2 - 有利誤認, yūri gonin), simply failing to disclose that a positive mention is an advertisement didn't neatly fit these categories unless the underlying claims were also false or misleading. The new designation under Article 5, Item 3 specifically targets the lack of disclosure itself as the misleading representation.

The regulation aims to address these issues by mandating clarity, ensuring consumers know when they are viewing an advertisement, thereby promoting informed choices and fair competition.

What is Regulated? The Core Prohibition and "Advertiser's Indication"

The regulation, formally designated under Article 5, Item 3 of the Keihyōhō, prohibits "representations made by an entrepreneur regarding transactions for its goods and services which would be difficult for ordinary consumers to recognize as such representations". In simpler terms, it bans advertisements that consumers can't easily identify as advertisements.

The crucial element is determining when a representation is considered to be made by the entrepreneur (the advertiser or business operator, 事業者 - jigyōsha). This concept is referred to as the "Advertiser's Indication" (事業者の表示 - jigyōsha no hyōji). The regulation clarifies that it only applies to indications that are substantively controlled or determined by the business supplying the goods or services. It does not regulate genuinely independent opinions or reviews posted by third parties (consumers, influencers, media) based on their own volition.

The key determining factor, according to the CAA's Operational Standards (運用基準 - un'yō kijun), is whether the business operator was involved in determining the content of the third party's representation. If the business exerts control or significant influence over what is said, how it's said, or even the overall message conveyed by a third party, that third party's post is likely to be considered the "Advertiser's Indication" and thus subject to the disclosure requirement.

Examples illustrating advertiser involvement include:

- Explicitly instructing a third party (e.g., an influencer) on the specific content to post (positive points to highlight, negative points to omit).

- Providing detailed directions on how to present the product/service.

- Requiring prior review and approval of the third party's content before publication.

- Structuring compensation in a way that heavily incentivizes specific types of positive portrayal.

Conversely, situations generally not considered "Advertiser's Indications" (meaning the third party's post is their own and not subject to the sutema rules solely based on the relationship) include:

- A consumer voluntarily posting a review after purchasing a product.

- An influencer receiving a product sample without obligation or specific instructions on what to post, allowing them full editorial freedom (though disclosure of the free item might still be best practice for transparency).

- A business soliciting reviews through general campaigns (e.g., "post a review and get a coupon") provided they do not dictate or attempt to control the content of those reviews (e.g., only allowing positive reviews, incentivizing 5-star ratings).

- Standard media relations activities where products are provided for journalistic review, assuming the media outlet retains full editorial independence.

The analysis hinges on the objective facts of the relationship and communication between the business and the third party – does the business effectively control the message? If so, it's likely their indication.

Scope of Application: All Media Covered

It is important to note that this regulation is not limited to online advertising or social media. The Keihyōhō applies broadly to representations made in connection with transactions. Therefore, stealth marketing practices are prohibited across all media, including:

- Online platforms (social media posts, blogs, video content, review sites, affiliate marketing sites)

- Print media (magazines, newspapers - e.g., advertorials disguised as articles)

- Broadcast media (television, radio - e.g., undisclosed product placements)

Any promotional representation attributable to the business operator, regardless of the medium, must be clearly identifiable as such by the average consumer.

Disclosure Requirements: Ensuring Recognizability

Since the core prohibition targets representations "difficult for general consumers to identify" as advertisements, the crucial compliance element is ensuring clear and conspicuous disclosure. The CAA's Operational Standards provide guidance on what constitutes adequate disclosure, making the commercial nature of the content readily apparent.

- Clear Language: The disclosure must use terms that unambiguously signal advertising. Examples provided include 「広告」 (kōkoku - advertisement), 「宣伝」 (senden - promotion), 「プロモーション」 (puromōshon - promotion), or 「PR」. English equivalents like "#ad" or "#sponsored" are also generally considered acceptable if clear to the target audience. Vague terms like "collaboration" or "partnership" might be insufficient if the relationship involves payment or control over the message.

- Prominent Placement: The disclosure must be easily visible and understandable to the consumer. It should not be hidden, buried in a long list of hashtags, placed "below the fold" requiring scrolling, or presented in a font size, color, or location that makes it difficult to notice. For video content, disclosure might need to appear within the video itself or persistently alongside it, not just in easily missed descriptions.

- Context Matters: The overall context is considered. If a representation is clearly within a dedicated advertising section of a website or publication, additional explicit labeling might not be necessary. However, for content integrated into non-advertising contexts (like an influencer's social media feed or a blog post), explicit disclosure is essential.

The fundamental principle is that the average consumer, encountering the representation, should immediately understand its commercial nature without needing to investigate further. Ambiguity or attempts to obscure the disclosure would likely violate the regulation.

Enforcement and Penalties: Orders and Reputational Risk

Unlike some other violations under the Keihyōhō (e.g., egregious false advertising related to quality or price), the stealth marketing designation itself does not currently trigger automatic administrative fines (kachōkin, 課徴金). However, this does not mean violations are without consequences.

- Administrative Orders (措置命令 - Sochi Meirei): The primary enforcement tool is an administrative order issued by the CAA under Article 7 of the Keihyōhō. If the CAA determines a representation constitutes prohibited stealth marketing, it can order the business operator (the advertiser) to:

- Cease the misleading representation.

- Take measures to prevent recurrence (e.g., implement compliance programs, educate employees and partners).

- Issue a public notice informing consumers about the misleading representation.

- Public Disclosure: The issuance of an administrative order is publicly announced by the CAA, including the name of the violating business. This public naming can cause significant reputational damage.

- Penalties for Non-Compliance: Failure to comply with an administrative order can lead to penalties, including imprisonment for up to two years or a fine of up to JPY 3 million for individuals representing the company, and potential fines for the corporation itself.

- Compliance Program Requirement: Businesses are generally required under Article 26 of the Keihyōhō to establish internal systems necessary to prevent misleading representations. A violation could indicate a failure in these systems, potentially leading to stricter scrutiny or requirements from the CAA.

- Reputational Damage (Enjō): Beyond formal sanctions, being publicly identified for engaging in stealth marketing can trigger severe consumer backlash and negative media attention (an enjō or "flaming incident"), causing lasting damage to brand trust and image. The mere issuance of a CAA order is often enough to cause significant harm.

Importantly, the regulation targets the business operator (advertiser) whose goods or services are being promoted. The third party (e.g., influencer, reviewer, publisher) making the post at the advertiser's behest is generally not directly subject to orders under the Keihyōhō for the stealth marketing violation itself, although they might face contractual consequences from the advertiser or platform, or separate liability if the content itself is defamatory or otherwise illegal.

The first enforcement action under the new regulation was taken in June 2024 against a medical corporation related to undisclosed favorable reviews, signaling the CAA's intent to actively enforce the rules.

Practical Implications for Businesses

Businesses advertising or selling in Japan, or engaging third parties to do so, need to adapt their practices to ensure compliance.

- Influencer Marketing: Contracts with influencers should explicitly require clear and conspicuous disclosure of the commercial relationship in all promotional content, specifying acceptable disclosure methods (e.g., #PR, #広告). Businesses should provide clear guidelines but avoid dictating specific opinions if they wish the content not to be deemed their own indication (a difficult balance). Monitoring influencer posts for compliance is advisable.

- User-Generated Content (UGC) and Reviews: Soliciting customer reviews is permissible, but businesses must not control the content. Offering incentives (coupons, points) for reviews is possible but requires careful handling. If incentives are offered, transparency about the incentive might be necessary, and directing users to write only positive reviews or manipulating ratings would likely cross the line into deceptive practices and potentially make the review the "advertiser's indication" requiring disclosure.

- Affiliate Marketing: Affiliate links and content should clearly disclose the affiliate relationship and that the publisher may earn a commission. Standard disclosures like "広告" or "PR" are generally required on pages featuring affiliate links.

- Native Advertising and Advertorials: Content designed to look like editorial material but paid for by an advertiser must be clearly labeled as advertising (e.g., 「広告」, 「PR」) in a way that is immediately obvious to the reader. Blurring the lines is the essence of what the regulation prohibits.

- Internal Compliance: Companies need internal guidelines and training programs for marketing teams and anyone involved in engaging third parties for promotion. Contracts with advertising agencies, PR firms, and influencers should include clauses mandating compliance with the Keihyōhō, including stealth marketing regulations. Vetting marketing partners for their understanding and adherence to these rules is crucial.

Comparison with US FTC Guidelines

While aiming for similar goals of transparency, the Japanese approach differs somewhat from the US Federal Trade Commission's (FTC) Endorsement Guides.

- Legal Basis: The Japanese rule is a specific designation under a general consumer protection law (Keihyōhō Art. 5(3)), while the FTC Guides interpret broader prohibitions against unfair or deceptive acts under the FTC Act.

- Focus: The Japanese regulation centers on whether a representation is an "Advertiser's Indication" based on content control, and if so, whether it's clearly identifiable as an advertisement. The FTC Guides focus more broadly on whether there is a "material connection" between the endorser and the advertiser that might affect the endorsement's credibility, requiring disclosure of that connection (e.g., payment, free product, employment). While often overlapping in practice, the analytical starting point differs slightly.

- Disclosure Specificity: The CAA guidelines recommend specific Japanese terms (広告, 宣伝, PR). The FTC emphasizes clarity and conspicuousness but is less prescriptive about exact wording, allowing terms like "Ad," "Sponsored," or platform-specific tools, as long as they are unambiguous.

- Enforcement: Both rely primarily on administrative actions against the advertiser/company, though the FTC has occasionally pursued actions against influencers or agencies in egregious cases, which seems less likely under the current Japanese framework focusing on the jigyōsha.

Despite differences, the underlying principle is the same: consumers have a right to know when they are seeing advertising.

Conclusion: Transparency as the New Standard

Japan's regulation of stealth marketing marks a significant shift towards greater transparency in advertising and promotion within the country. By designating advertisements not clearly identifiable as such as misleading representations under the Keihyōhō, the Consumer Affairs Agency has established a clear legal standard applicable across all media platforms.

For businesses operating in or marketing to Japan, the message is unambiguous: disguise is no longer an option. Ensuring that all promotional content directly controlled or substantively influenced by the business is clearly and conspicuously disclosed as advertising is now a legal requirement. Proactive compliance, including clear internal guidelines, robust contractual terms with partners and influencers, and ongoing monitoring, is essential to avoid administrative sanctions and the potentially more damaging consequences of public backlash and reputational harm. Transparency is not just best practice; it is the required standard for engaging with Japanese consumers.

- Digital Deception or Fair Play? Applying Japan's Premiums and Representations Act to Online Advertising

- IP Management for Startups & Universities in Japan: Protecting and Leveraging Innovation

- Protecting the Edge: Japan's Evolving Export Controls and New Patent Secrecy Regime for Technology Companies

- Consumer Affairs Agency – Stealth Marketing Guidelines