Unlocking the Past: An Heir's Right to Access Deceased's Bank Records in Japan

Date of Judgment: January 22, 2009

Case Name: Claim for Disclosure of Deposit Transaction Records

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

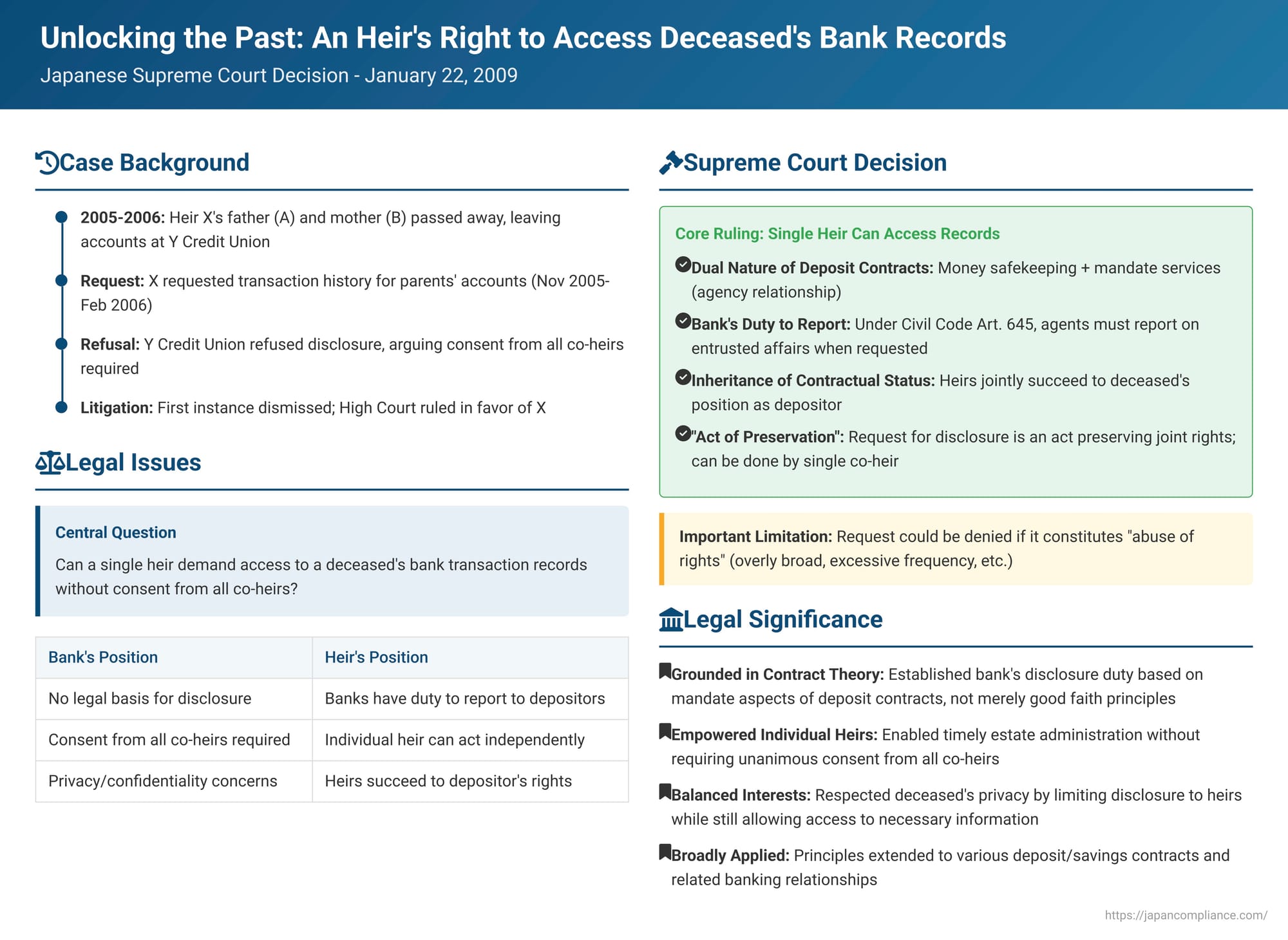

When a family member passes away, settling their estate often requires a thorough understanding of their financial affairs. Accessing the deceased's bank account transaction history can be crucial for heirs to identify assets, understand financial activities leading up to the death, and ensure a fair distribution of the estate. A Japanese Supreme Court decision from January 22, 2009, provided significant clarification on the rights of an individual heir to obtain such records from a financial institution, even without the express consent of all other co-heirs.

The Inheritance Puzzle: Seeking Account Transparency

The case arose from the following circumstances:

- The Deceased Depositors and Heir: A (the father of X) passed away on November 9, 2005, and B (the mother of X) passed away on May 28, 2006. X was one of the co-heirs to the estates of both A and B.

- Bank Accounts Held: At the time of A's death, A held one ordinary deposit account and eleven time deposit accounts with a specific branch of Y Credit Union. B also held one ordinary deposit account and two time deposit accounts at the same branch.

- Request for Disclosure and Refusal: X requested Y Credit Union to disclose the transaction history for B's (mother's) accounts for the period from November 9, 2005, to February 15, 2006. Y Credit Union refused this request. (During the subsequent legal proceedings, X also added a claim for disclosure of A's (father's) account transaction history for November 8 and 9, 2005). The refusal was, at least in part, based on the argument that consent from all co-heirs was necessary or that disclosure would breach privacy obligations.

- Litigation: X sued Y Credit Union to compel the disclosure.

- The first instance court initially dismissed X's claim, finding no specific legal basis to force the disclosure.

- However, the High Court, on appeal, ruled entirely in favor of X. It reasoned that a deposit agreement is not merely for the safekeeping of money (like a consumption deposit, where the bank can use the funds but owes an equivalent amount back) but also inherently involves the bank performing various services for the depositor, which have the nature of a mandate or quasi-mandate (agency-like services). Based on this, the High Court found that a financial institution has a good-faith duty, ancillary to the deposit contract, to disclose transaction history to the depositor. It further held that co-heirs jointly inherit the deceased's contractual status as a depositor, and any single co-heir can individually exercise the right to request this information as an "act of preservation" of their shared inherited rights.

Y Credit Union appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, arguing that there was no legal foundation for such a disclosure right, and that even if one existed, a single co-heir could not unilaterally demand it due to the bank's duties of confidentiality and the privacy interests of the deceased and other co-heirs.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation

The Supreme Court, in its judgment on January 22, 2009, dismissed Y Credit Union's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision that X was entitled to the disclosure.

The Legal Basis for Disclosure: More Than Just a Deposit

The Supreme Court provided a foundational analysis of the nature of a deposit contract:

- Dual Nature of Deposit Contracts: A deposit contract indeed involves the depositor entrusting money to the financial institution and the institution owing back an equivalent sum (the nature of a "consumption deposit" or irregular deposit). However, the Court emphasized that a bank, under a deposit contract, also performs numerous administrative and transactional services for the depositor. These services include accepting incoming fund transfers, processing automatic payments for utilities, crediting interest, and handling automatic renewals of time deposits. These services, the Court stated, have the character of mandate or quasi-mandate (委任・準委任 - inin/jun-inin) – essentially, agency services.

- Agent's Duty to Report (Civil Code Article 645): Under Japanese Civil Code Article 645 (and Article 656 for quasi-mandates), an agent (in this context, the bank) has a duty to report to the principal (the depositor) on the status of the entrusted affairs when requested. The rationale for this duty is that it is essential for the principal to be able to accurately understand how their affairs are being managed and to assess whether the agent is performing their duties appropriately.

- Application to Bank Transactions: This principle applies directly to banking transactions. The transaction history of a bank account is a direct reflection of the financial institution's performance of these mandated administrative duties. Therefore, access to this history is crucial for the depositor to accurately comprehend the changes in their deposit balance, the reasons for those changes, and to verify that the financial institution has handled all transactions correctly.

- Contractual Duty of Disclosure: Consequently, the Supreme Court concluded that financial institutions have a duty, arising from the deposit contract itself (due to its mandate-like aspects), to disclose the account transaction history to the depositor upon request.

An Individual Heir's Right to Request Disclosure

Having established the bank's duty to the depositor, the Court then addressed the rights of a co-heir:

- Inheritance of Contractual Status: When a depositor dies, their co-heirs not only inherit shares in the monetary value of the deposit claim but also jointly succeed to the deceased's contractual status as a depositor under the deposit agreement with the financial institution.

- Disclosure Request as an "Act of Preservation": Based on this inherited contractual status, a single co-heir is entitled to individually exercise the right to demand disclosure of the deceased depositor's account transaction history. The Court characterized this request as an "act of preservation" (保存行為 - hozon kōi) concerning the jointly inherited contractual rights. Under Japanese law (Civil Code Article 264, applying Article 252 proviso for co-owned property), acts of preservation can be undertaken by any co-owner individually, without requiring the consent of all other co-owners.

- Lack of Other Heirs' Consent Not a Bar: Therefore, the absence of consent from other co-heirs does not prevent one co-heir from validly requesting and obtaining the transaction history.

Addressing Privacy and Confidentiality Concerns

Y Credit Union had argued that disclosing a deceased depositor's account history to just one co-heir would violate the deceased's privacy and the bank's duty of confidentiality. The Supreme Court succinctly dismissed this argument, stating that as long as the disclosure is made to a co-heir, such privacy or confidentiality issues do not arise. This implies that co-heirs are not viewed as unrelated third parties in this context but as successors to the depositor's own right to information.

Caveat: Potential for Abuse of Rights

The Supreme Court did acknowledge a limitation: a request for disclosure could, depending on its specific manner, the scope of information sought, or its frequency, potentially constitute an abuse of rights and thus be legitimately denied by the financial institution. However, in the specific circumstances of X's request, the Court found no evidence of such abuse.

The Broader Implications

This 2009 Supreme Court decision was significant as it provided a definitive resolution to an issue where lower court precedents had been divided. It established a clear legal framework for an individual heir's right to access a deceased's bank records.

Grounding the Disclosure Duty

The judgment firmly anchors the financial institution's duty of disclosure in the mandate-like aspects of the deposit contract and the agent's reporting obligation under Civil Code Article 645. This provided a more solid legal footing than relying on general good faith principles alone, which had been a basis in some prior discussions.

Understanding the "Act of Preservation"

By framing the heir's request for information as an "act of preservation" of the inherited contractual position, the Court enabled individual action. This is important because requiring unanimous consent from all co-heirs for such a basic informational request could lead to deadlock and hinder the timely administration of estates, especially in cases of family disputes.

Practical Limits – Abuse of Rights

While the right to disclosure is established, it is not unlimited. The "abuse of rights" caveat is important. Legal commentary suggests that this might come into play if, for example, an heir makes unnecessarily fragmented and repeated requests for small pieces of information, or demands disclosure of an excessively long transaction history (e.g., since account opening decades ago) without a specific and reasonable justification, or insists on detailed disclosure of individual transaction slips where a summary history would suffice for the stated purpose. The key consideration would likely be whether the request aligns with the legitimate purposes for which an agent must report to a principal – i.e., to allow the principal (or their successor heir) to understand and evaluate the bank's handling of the entrusted affairs.

Scope and Future Relevance

The Supreme Court has subsequently indicated (e.g., in a 2016 Grand Bench decision concerning divisibility of deposit claims in inheritance) that the principles regarding a bank's duty to disclose transaction history apply broadly to "deposit and savings contracts" (預貯金契約 - yochokin keiyaku) in general. Given that Article 645 of the Civil Code also covers an agent's reporting duties after the termination of a mandate, this framework logically extends to allow heirs to request transaction history even if the account was closed shortly before or after the depositor's death.

Conclusion

The 2009 Japanese Supreme Court decision significantly empowers individual heirs by affirming their right to independently access a deceased relative's bank account transaction history. By grounding this right in the fundamental, mandate-like nature of the deposit contract between the customer and the financial institution, the Court provided much-needed clarity. This ruling strikes a balance: it ensures that heirs can obtain information vital for estate administration while also acknowledging that such requests must be exercised reasonably and not constitute an abuse of rights. It serves as a clear guidepost for both bereaved families and financial institutions in navigating the often complex process of settling a loved one's financial affairs.