Unlocking Prison Medical Records: Japan's Supreme Court Affirms Inmates' Right to Access Their Own Health Information

Judgment Date: June 15, 2021

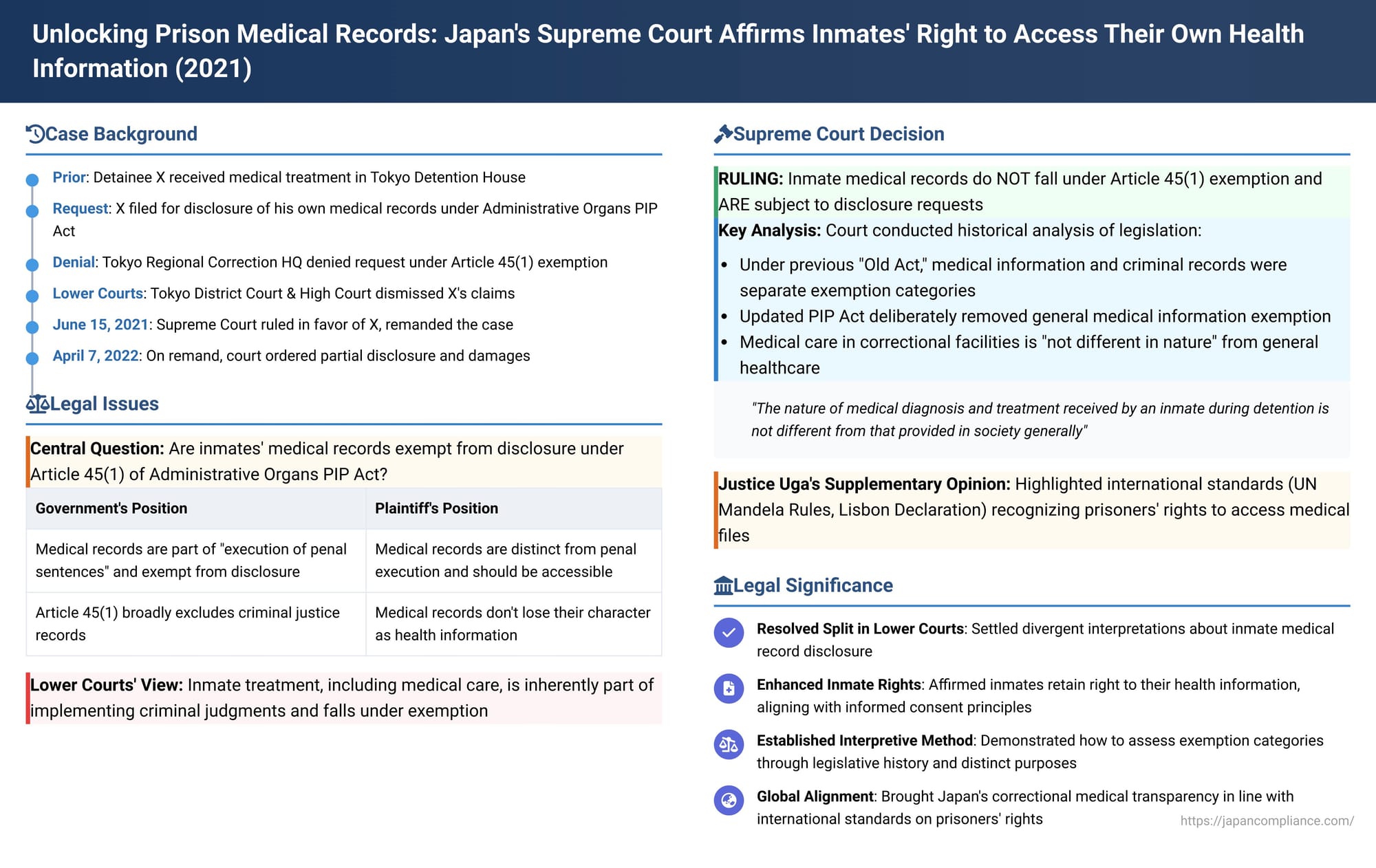

The right of individuals to access their own personal information held by government agencies is a key tenet of modern data protection regimes. However, this right often encounters complexities when applied to sensitive environments like correctional facilities. A landmark decision by Japan's Supreme Court on June 15, 2021 (Reiwa 2 (Gyo-Hi) No. 102), addressed a crucial aspect of this issue: whether medical records of inmates held by penal institutions are subject to standard disclosure requests, or if they fall under broad exemptions related to the execution of criminal justice. This ruling significantly clarified the scope of inmates' rights to access their own health information.

The Detainee's Request: Seeking Medical Transparency Behind Bars

The plaintiff, X, while an unsentenced detainee at the Tokyo Detention House, requested access to his medical records concerning treatment received during his detention. This request was made under Japan's Act on the Protection of Personal Information Held by Administrative Organs (hereinafter, the "Administrative Organs PIP Act," prior to its abolition and integration into a revised comprehensive Personal Information Protection Act by the Digital Society Formation Legislation of 2021).

The Head of the Tokyo Regional Correction Headquarters, representing the State (Y), denied X's request in its entirety. The basis for this refusal was Article 45, paragraph 1 of the Administrative Organs PIP Act. This provision stipulated that Chapter 4 of the Act—which covers rights to disclosure, correction, and suspension of use of personal information—does not apply to certain categories of "retained personal information." These excluded categories broadly pertain to information related to:

- Judgments in criminal cases or juvenile protection cases.

- Dispositions made by prosecutors, prosecutor's assistant officers, or judicial police officials.

- The execution of penal sentences or protective measures.

- Rehabilitation emergency protection or pardons (limited to information concerning the individuals who were subject to such judgments, dispositions, execution, or applications/proposals for such measures).

The correctional authorities argued that X's medical records fell within this exclusion, specifically as information related to the "execution of penal sentences" or "judgments in criminal cases," and were therefore not subject to disclosure requests. X subsequently filed a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of this non-disclosure decision and also claimed damages under the State Compensation Act.

The Tokyo District Court and the Tokyo High Court both dismissed X's claims. These lower courts reasoned that the overall "treatment" (shogū) of inmates, including medical care, is inherently and necessarily incidental to implementing the content of criminal judgments. They expressed concern that if such personal information were subject to disclosure requests, it could be misused by third parties (e.g., for scrutinizing past criminal records when an individual seeks employment), thereby hindering the social reintegration of the person concerned. Since medical treatment provided to inmates is considered a part of this comprehensive "treatment," information related to it, unless specifically stipulated otherwise, was deemed to fall under the exclusionary scope of Article 45, paragraph 1.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (June 15, 2021): A Shift in Interpretation

The Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, overturned the lower courts' decisions and remanded the case. The Court undertook a detailed historical and textual analysis of the relevant legal provisions.

Historical Legislative Context (The "Old Act")

The Supreme Court began by examining the legislative predecessor to the Administrative Organs PIP Act: the Act on the Protection of Personal Information Held by Administrative Organs Processed by Electronic Computers (commonly referred to as the "Old Act," which was wholly revised in 2003 to become the Administrative Organs PIP Act).

- The Old Act had a provision (Article 13, paragraph 1, proviso) that excluded from disclosure requests personal information files recording "matters related to criminal judgments, etc." (keiji saiban tō kankei jikō). The Supreme Court noted that the rationale for this exclusion was to prevent information like an individual's criminal record or history of incarceration from being used by third parties in ways that could impede the individual's social rehabilitation (e.g., employers requiring submission of disclosure request results during hiring).

- The Old Act also allowed for certain personal information files used in connection with the execution of detention, corrections, or rehabilitation protection (under Article 7, paragraph 3, item 3) to be omitted from the publicly available "personal information file register" if their inclusion was deemed likely to significantly hinder the proper execution of the related administrative duties. Information from such unlisted files was also excluded from disclosure requests (Article 13, paragraph 1, main text).

- Crucially, the Old Act's Article 13, paragraph 1 proviso, separately from the "matters related to criminal judgments, etc.," also excluded from disclosure requests processing information from personal information files that recorded "matters related to medical diagnosis or treatment in hospitals, clinics, or midwifery homes" ("medical diagnosis/treatment related matters" - shinryō kankei jikō). The Supreme Court explained that this particular exclusion was based on the prevailing view at the time that decisions regarding the disclosure of medical information were best left to the medical judgment of those involved in the treatment, based on the trust relationship between patient and provider.

Nature of Inmate Medical Care

The Supreme Court then emphasized the legal nature of medical care provided within correctional facilities. Under laws such as the Act on Penal Detention Facilities and Treatment of Inmates and Detainees (Penal Detention Facilities Act), Article 56, correctional facilities are obligated to take appropriate health and medical measures for inmates, consistent with the general standards of public health and medical care in society. Hospitals and clinics within these facilities are, in principle, subject to the Medical Act (Medical Act, Art. 30-2; Medical Act Enforcement Order, Art. 3(2)). Doctors and dentists providing treatment in these settings must adhere to the Physicians Act or Dentists Act respectively. Consequently, the Supreme Court concluded that "the nature of medical diagnosis and treatment received by an inmate during detention is not different from that provided in society generally". This was also the situation under the old Prison Act, which was in force when the Old Act was enacted.

Given this, the Supreme Court reasoned that under the Old Act, personal information files concerning medical treatment received by inmates during detention were naturally understood to be excluded from disclosure under the category of "medical diagnosis/treatment related matters," not as "matters related to criminal judgments, etc." or matters related to the execution of detention as per Article 7(3)(3) of the Old Act.

Interpreting Article 45(1) of the (then current) Administrative Organs PIP Act

With this historical context, the Supreme Court turned to Article 45, paragraph 1 of the Administrative Organs PIP Act (the provision cited by the government to deny X's request).

- The Court found that this provision, established through the 2003 wholesale revision of the Old Act, based on its text and other factors, carries a purpose similar to the Old Act's exclusion of "matters related to criminal judgments, etc.". Article 45(1) was designed to exclude from the Act's disclosure provisions (Chapter 4) not only information related to "matters related to criminal judgments, etc.," but also information pertaining to administrative duties like detention execution and corrections (which were covered by Article 7(3)(3) of the Old Act), provided such information aligns with the overarching aim of preventing the misuse of criminal record-type information that could hinder social reintegration.

- However, the Court pointed out a critical change made during the 2003 revision: the Administrative Organs PIP Act did not incorporate a provision to generally exclude "medical diagnosis/treatment related matters" from disclosure requests. The Supreme Court stated that the legislative intent behind this omission was to expand the scope of disclosure as much as possible, recognizing the importance of citizens' interest in accessing personal information held by administrative organs. This change also reflected evolving societal views, including the growing acceptance of the principle of informed consent in medical practice, and public opinion favoring greater access to medical information.

- The Supreme Court found no indication that, when Article 45(1) was newly established, there was any specific legislative consideration to exclude medical information of inmates—which, as established, is not different in nature from general societal medical care—from the disclosure provisions of Chapter 4 of the Act. Furthermore, the Court found no other basis for interpreting Article 45(1) to include such inmate medical information within its scope of excluded categories.

Conclusion: Inmate Medical Records Are Subject to Disclosure Requests

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court concluded: "personal information concerning medical diagnosis and treatment received by an inmate during detention does not fall under the category of retained personal information stipulated in Article 45, paragraph 1 of the Administrative Organs Personal Information Protection Act". Therefore, such information is subject to disclosure requests made under Article 12, paragraph 1 of the Act.

Justice Katsuya Uga's Concurring Thoughts: Informed Consent and Global Standards

Justice Katsuya Uga, in a supplementary opinion, reinforced the majority's conclusion by emphasizing the importance of informed consent in medical treatment, a principle that does not lose its relevance for medical information generated within correctional facilities. He referenced international standards, including Rule 26(1) of the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Mandela Rules), which states that prisoners should have access to their medical files upon request. This underscores that access to one's own medical information, even while detained, aligns with global norms. Justice Uga also pointed to the Lisbon Declaration on the Rights of the Patient by the World Medical Association, affirming a patient's right to receive information from their medical records and a full explanation of their health status.

The Rationale Explained (Commentary Insights)

This Supreme Court decision is highly significant, particularly as it resolved a split among lower court judgments on whether inmate medical records were excluded from disclosure under Article 45(1) of the Administrative Organs PIP Act. Given reports of numerous disclosure requests for inmate medical records, often stemming from dissatisfaction with treatment, the ruling carries substantial practical importance.

- Diverging Lower Court and Review Board Stances: Prior to this Supreme Court judgment, many lower court rulings had affirmed non-disclosure of inmate medical records, typically reasoning that inmate medical care was an inseparable part of their overall "treatment" or "sentence execution," thus falling under the Article 45(1) exclusion designed to protect against misuse of criminal history-type information. The Information Disclosure and Personal Information Protection Review Board had also consistently held that inmate medical information fell under this exclusion. However, at least one Osaka High Court decision had diverged, finding Article 45(1) inapplicable.

- Supreme Court's Methodical Interpretation: The Supreme Court's theoretical framework involved a careful step-by-step analysis:

- It began by interpreting the corresponding provisions in the Old Act, highlighting that "matters related to criminal judgments, etc." and "medical diagnosis/treatment related matters" were distinct exclusion categories with different underlying rationales.

- It affirmed that, under relevant laws, medical care provided to inmates is not substantively different from medical care in general society.

- From this, it deduced that under the Old Act, inmate medical information was excluded by virtue of being "medical diagnosis/treatment related matters," not due to being "matters related to criminal judgments, etc.".

- Finally, it interpreted Article 45(1) of the (then current) Administrative Organs PIP Act. It noted that this article was intended to cover information akin to "matters related to criminal judgments, etc." and certain related administrative affairs concerning corrections and rehabilitation. Crucially, the general exclusion for "medical diagnosis/treatment related matters" that existed in the Old Act was not carried over into the Administrative Organs PIP Act. This omission was seen as a deliberate legislative choice reflecting a policy of broader disclosure and informed consent in the medical sphere. This led to the conclusion that inmate medical information, being primarily medical in nature, was not encompassed by the exclusion in Article 45(1).

- Relevance to the New Unified Personal Information Protection Act: The Administrative Organs PIP Act was repealed and its provisions largely integrated into a revised, comprehensive Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI) by the Digital Society Formation Legislation, effective from September 1, 2021. Article 122 of this newly revised APPI (which became Article 124 after a further amendment scheduled to be effective by May 18, 2023) contains exclusionary wording identical to that of the old Article 45(1). Therefore, the Supreme Court's reasoning in this 2021 judgment is directly applicable to the interpretation of the corresponding exclusion under the current APPI.

- Remand for Consideration of Other Non-Disclosure Grounds: The Supreme Court remanded the case to the Tokyo High Court for further proceedings concerning X's cancellation request. This was because the Supreme Court's ruling only addressed the inapplicability of the Article 45(1) blanket exclusion. It did not rule on whether other specific non-disclosure grounds under Article 14 of the Administrative Organs PIP Act (e.g., protection of third-party privacy, risk to the security of the correctional facility, etc.) might legitimately apply to portions of X's medical records. The government (correctional authority) would be entitled to argue these other specific grounds on remand.

The Story After Remand: Partial Victory and State Compensation

Following the Supreme Court's decision, the case returned to the Tokyo High Court. In its judgment on April 7, 2022, the remand court noted that the Head of the Tokyo Regional Correction Headquarters had subsequently issued a new decision, this time making a partial disclosure of X's medical records. Only portions deemed non-disclosable under Article 14, item 5 (risk of hindering proper execution of administrative affairs related to criminal investigations, trials, or sentence execution) and item 7 (risk to maintaining discipline and order in penal institutions) of the Administrative Organs PIP Act were withheld. Consequently, X's original lawsuit seeking the cancellation of the initial total non-disclosure decision was dismissed as lacking legal interest with respect to the parts that had since been disclosed.

However, X's claim for state compensation saw a significant development. The remand court found that officials at the Ministry of Justice had been negligent. It ruled that if these officials had exercised the due care required by their duties, they should have recognized that inmate medical records were not covered by the Article 45(1) exclusion. The court found that the Ministry's incorrect interpretation had become a systemic, organizational one. This negligence in adopting and maintaining an erroneous legal interpretation, which directly led to the wrongful initial total non-disclosure, was deemed sufficient to render the original non-disclosure decision illegal for the purposes of state compensation under Article 1, paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act. The court also found that the Ministry officials were at fault (negligent). As a result, X was awarded damages, including compensation for emotional distress and delay damages.

Implications for Prisoners' Rights and Correctional Transparency

The Supreme Court's 2021 decision is a significant step forward for prisoners' rights and transparency in healthcare within correctional facilities in Japan.

- Enhanced Access to Health Information: It directly affirms the right of inmates to request access to their own medical records under the general provisions of personal information protection law, clarifying that such records are not automatically swept under broad exclusions meant for criminal justice process information.

- Potential for Greater Medical Accountability: Easier access to medical records can empower inmates to better understand their treatment, seek second opinions where appropriate, and potentially hold correctional medical services more accountable for the quality of care provided.

- Guidance for Interpreting Exclusionary Clauses: The decision provides important guidance on narrowly interpreting broad exclusionary clauses in information protection laws, particularly by looking at legislative history and the distinct purposes of different types of information.

Conclusion

The June 15, 2021, Supreme Court judgment marks a pivotal moment in affirming the right of inmates in Japan to access their own medical information. By meticulously dissecting the legislative history and the distinct natures of penal information versus medical information, the Court concluded that medical records generated during incarceration are generally subject to disclosure requests, just like medical records in the wider community. This decision not only enhances the rights of a vulnerable population but also promotes greater transparency and potential accountability in the provision of healthcare within correctional institutions. The subsequent success of the plaintiff's state compensation claim on remand further underscores the responsibility of government agencies to correctly interpret and apply laws concerning fundamental rights to information.