Unlocking Foreign Judgments: How Japan's Supreme Court Redefined 'Reciprocity'

Date of Judgment: June 7, 1983

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

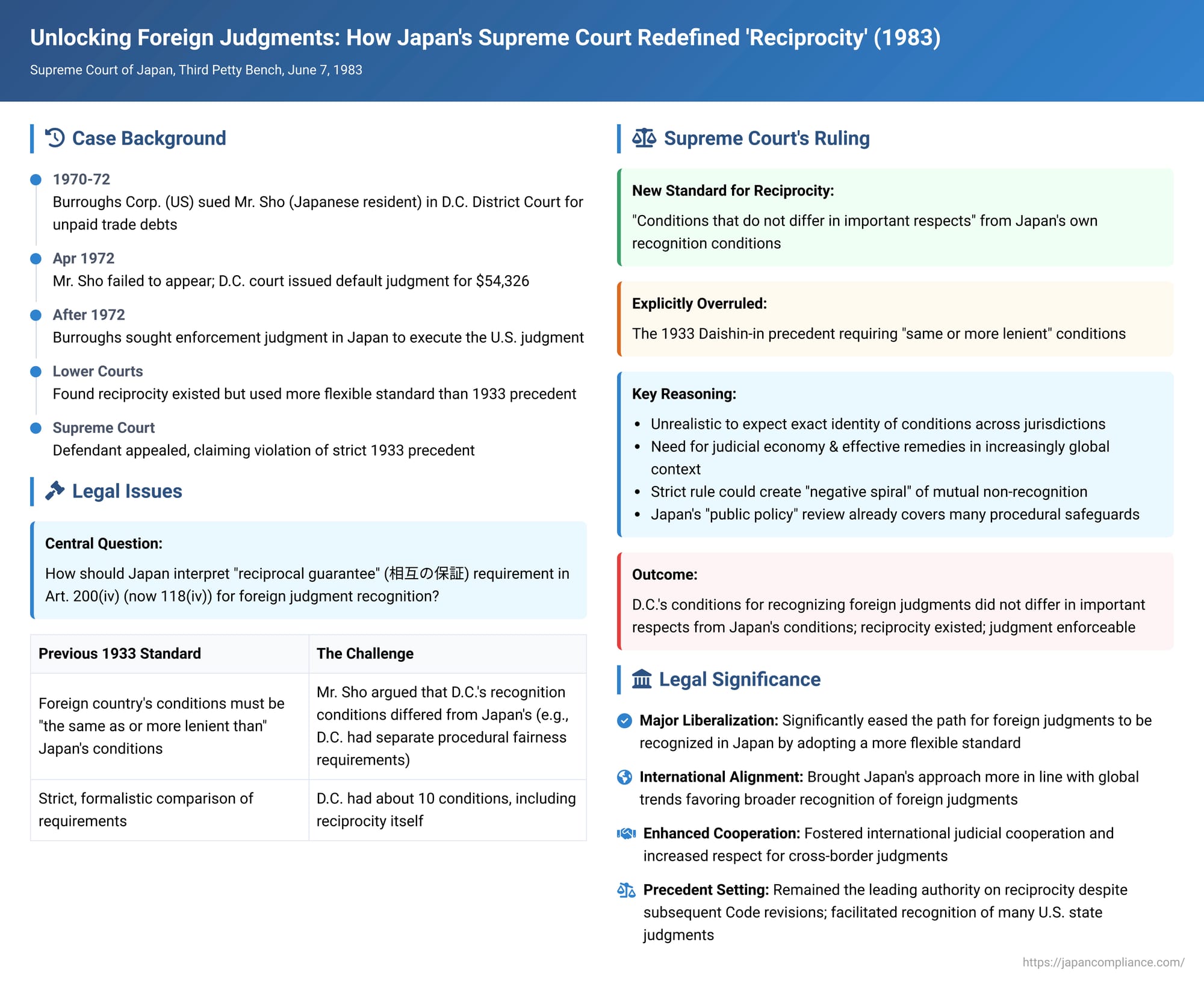

For a judgment obtained in a foreign court to be recognized and enforced in Japan, it must satisfy several conditions laid out in Japan's Code of Civil Procedure. One of the most debated of these historically has been the requirement of "reciprocal guarantee" (相互の保証 - sōgo no hoshō). This essentially asks whether the country where the foreign judgment was rendered would, in turn, recognize similar Japanese judgments. A landmark Supreme Court decision on June 7, 1983, in a case involving the enforcement of a U.S. default judgment, significantly liberalized the interpretation of this reciprocity requirement, making it easier for foreign judgments to be given effect in Japan.

The Factual Background: Seeking to Enforce a U.S. Default Judgment in Japan

The case involved a U.S. corporation seeking to enforce a judgment against an individual residing in Japan:

- X Corp. (Plaintiff): Burroughs Corporation, a U.S. company.

- Y (Defendant): Mr. Teiryu Sho (Chung Tai-yong), an individual.

- A Corp.: A company for which Y was the representative director.

- The U.S. Lawsuit and Judgment: Around November 1970, X Corp. initiated a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia (D.C.) against Y, A Corp., and another entity to recover outstanding trade debts. Mr. Y failed to appear in the D.C. court despite being summoned. Consequently, on April 27, 1972, the D.C. court issued a default judgment ("Foreign Judgment") in favor of X Corp., ordering Y to pay over $54,326. This judgment subsequently became final.

- Enforcement Action in Japan: X Corp. then brought proceedings in a Japanese court seeking an "enforcement judgment" (執行判決 - shikkō hanketsu). This is a necessary step under Japanese law to enable compulsory execution in Japan based on a foreign court's judgment.

The lower courts in Japan (Tokyo District Court and Tokyo High Court) examined the conditions for recognition under Article 200 of the old Code of Civil Procedure (the provisions of which are now found in Article 118 of the current Code). They found that the first three conditions (jurisdiction of the foreign court, proper service or appearance by the defendant, and public policy) were met.

Regarding the fourth condition, reciprocity, the first instance court, based on expert testimony, identified ten conditions under D.C. law for recognizing foreign judgments. These included requirements such as the rendering court having jurisdiction, proper notice and opportunity to defend, fair procedure, finality, and not being contrary to D.C.'s public policy. Crucially, one of D.C.'s conditions was also a requirement of reciprocity from the country whose judgment was sought to be recognized. The first instance court concluded that reciprocity doesn't demand an exact match of conditions, only similarity in "important points," and found the requirement satisfied. The High Court upheld this.

Mr. Y appealed to the Supreme Court, primarily arguing that this interpretation of reciprocity conflicted with a long-standing precedent from the Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation, Japan's pre-WWII highest court). That 1933 Daishin-in ruling had established a much stricter test, requiring that the foreign country’s conditions for recognizing Japanese judgments be "the same as or more lenient than" Japan's own conditions.

The Core Legal Question: What Does "Reciprocal Guarantee" Mean for Enforcing Foreign Judgments?

The central issue for the Supreme Court was how to interpret the reciprocity requirement in Article 200(iv) of the old Code of Civil Procedure (now Article 118(iv)). Specifically, did it demand that the foreign jurisdiction's rules for recognizing Japanese judgments be identical to, or more lenient than, Japan's rules for recognizing that foreign jurisdiction's judgments?

The Supreme Court's Landmark Interpretation of Reciprocity

The Supreme Court dismissed Mr. Y's appeal, thereby upholding the enforceability of the D.C. judgment. In doing so, it fundamentally reshaped the understanding of reciprocity in Japanese law:

1. Overruling the Strict Daishin-in Precedent:

The Court explicitly overruled the 1933 Daishin-in decision and its stringent test for reciprocity.

2. New Standard: "Conditions Not Differing in Important Respects":

The Supreme Court held that the "reciprocal guarantee" requirement means that in the country where the foreign judgment was rendered (the "judgment country"), judgments of the same kind issued by Japanese courts are recognized as effective under conditions that do not differ in important respects from the conditions prescribed in Japan's own Code of Civil Procedure for recognizing foreign judgments.

- Rationale for Liberalization:

- Practicality: It is unrealistic to expect a foreign country to have recognition conditions that are exactly identical to Japan's, especially in the absence of a specific treaty codifying such terms.

- Needs of International Society: In an era of significantly expanded cross-border interactions, there is a growing need to prevent conflicting judgments concerning the same parties and to promote judicial economy and effective legal remedies. Interpreting the reciprocity clause to require only substantial equivalence of recognition conditions serves these contemporary needs.

- Avoiding Absurd Outcomes: The old, stricter Daishin-in rule could lead to an illogical "negative spiral." If a foreign country (Country F) also required reciprocity and its own recognition rules were, for example, more lenient than Japan's, Country F might find Japan's (stricter) rules not to meet its reciprocity standard. This would cause Country F to refuse recognition of Japanese judgments. Consequently, Japan, applying the strict Daishin-in test, would then find that Country F does not offer reciprocity to Japanese judgments, leading to mutual non-recognition. The Supreme Court found such a result "unreasonable."

3. The Role of Public Policy in Assessing Equivalence:

The Supreme Court also noted that when determining if reciprocity exists, Japan's public policy requirement (Article 118(iii), formerly Art. 200(iii)) should be understood to mean that not only the content of the foreign judgment but also the procedure by which it was established must not violate Japan's public order or good morals. This broader understanding of public policy allows for a more holistic comparison of the overall recognition systems. Even if the D.C. law listed more specific procedural safeguards for recognizing foreign judgments than were explicitly itemized in Japan's Article 118(ii) (service/appearance), many of these additional D.C. requirements could be seen as aspects implicitly covered by Japan's broader public policy review of procedural fairness. This allowed the Court to find that the overall sets of conditions in D.C. and Japan were not "different in important respects," despite variations in their specific articulation.

Application to the D.C. Judgment:

The Supreme Court concluded that the conditions under which the District of Columbia recognized foreign money judgments (as presented through expert evidence in the lower courts) did not differ in important respects from the conditions Japan itself applied under its Code of Civil Procedure. Therefore, the requirement of "reciprocal guarantee" was satisfied.

Significance and Impact

This 1983 Supreme Court ruling was a watershed moment for the enforcement of foreign judgments in Japan:

- Major Liberalization of Reciprocity: By explicitly overturning a restrictive 50-year-old precedent, the Court significantly eased the path for foreign judgments to be recognized and enforced. The shift to a "substantially equivalent conditions" or "not differing in important respects" standard was a pragmatic move welcomed by legal scholars and practitioners.

- Promotion of International Judicial Cooperation: The new, more flexible interpretation was seen as fostering international judicial cooperation and increasing the likelihood that judgments would be respected across borders, thereby enhancing legal certainty in international transactions and relationships.

- Alignment with International Trends: This decision brought Japan's approach to reciprocity more in line with a growing international tendency to favor broader recognition of foreign judgments, rather than imposing overly strict or identical requirements.

- Continued Relevance: While Japan's Code of Civil Procedure has undergone revisions since 1983, the fundamental interpretation of Article 118(iv) on reciprocity laid down in this case remains the leading authority.

- State-by-State (or Jurisdiction-by-Jurisdiction) Analysis for U.S. Judgments: It's important to remember that for judgments from federal systems like the United States, reciprocity is typically assessed on a state-by-state (or, as in this case, D.C.) basis. Following this liberalized standard, Japanese courts have subsequently found reciprocity to exist with numerous U.S. states, often because those states have adopted versions of the Uniform Foreign Money-Judgments Recognition Act, which sets out conditions generally seen as compatible with Japan's.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1983 decision in the Burroughs Corp. v. Sho case fundamentally modernized Japan's approach to the reciprocity requirement for the enforcement of foreign judgments. By replacing an outdated, rigid standard with a more flexible and practical test of "conditions not differing in important respects," the Court significantly enhanced the prospects for international judicial cooperation and made it more feasible for parties to obtain effective legal remedies across national borders. This ruling underscores a commitment to facilitating the flow of justice in an increasingly interconnected global environment.