Unlocking Evidence in Japanese IP Litigation: Procedures and Strategies

TL;DR

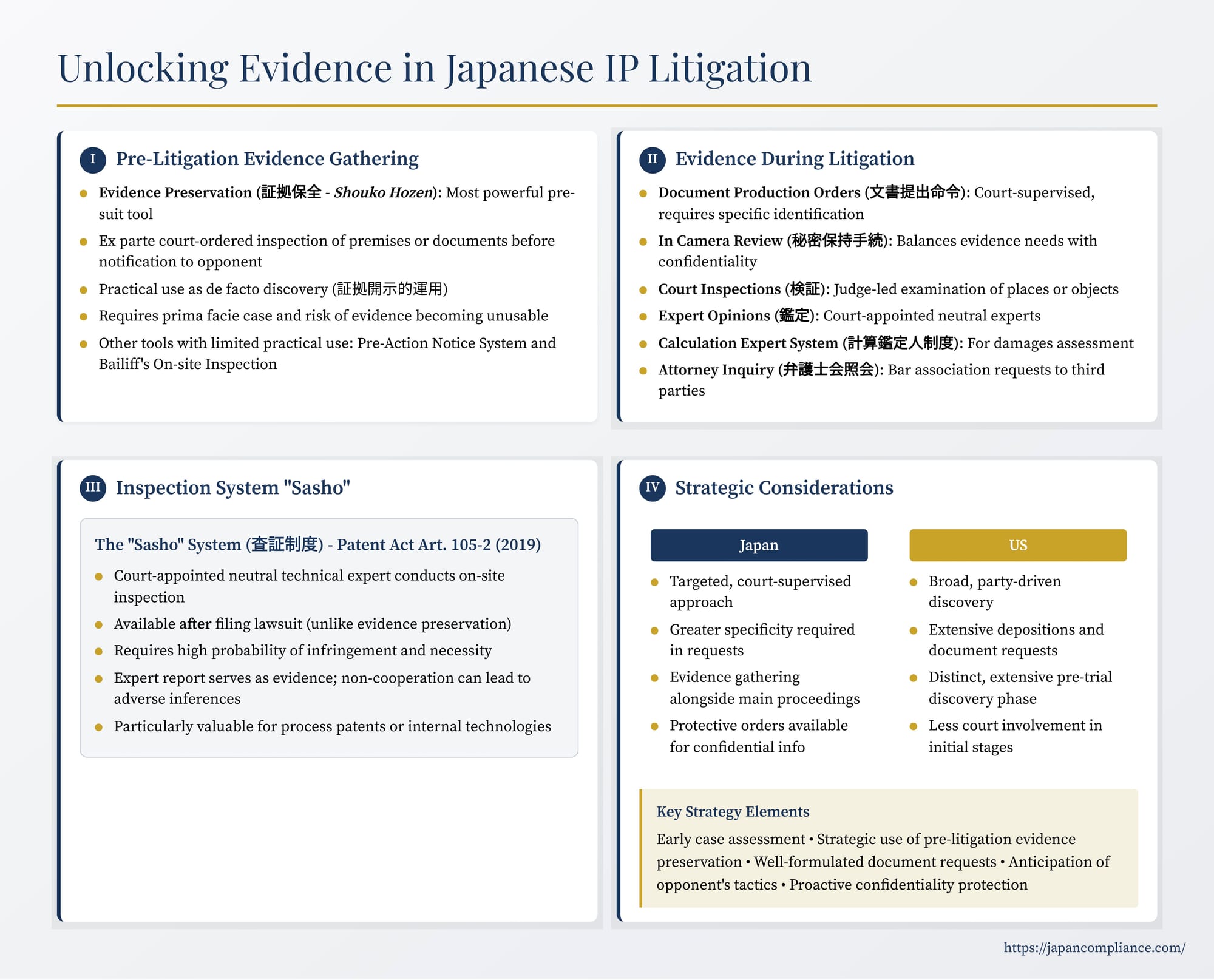

- Japan lacks US-style broad discovery, but IP litigants have targeted tools: pre-suit evidence preservation, document production orders with in-camera review, court inspections, and the new expert-led sashou system.

- Success hinges on early assessment, specific requests, and strategic use of these court-controlled mechanisms while safeguarding trade secrets with protective orders.

- Plaintiffs should act quickly to secure volatile evidence; defendants must prepare for surprise preservation orders and craft confidentiality arguments.

Table of Contents

- Pre-Litigation Evidence Gathering: Limited but Potent Tools

- Evidence Gathering During Litigation

- The Inspection System (“Sashou” Procedure)

- Protecting Confidential Information

- Strategic Considerations and Comparison with US Discovery

- Conclusion

Successfully litigating intellectual property rights often hinges on accessing crucial evidence, particularly evidence held by the opposing party. However, the procedures for obtaining such evidence vary significantly across jurisdictions. While practitioners familiar with the broad discovery process in the United States might expect similar mechanisms elsewhere, Japan employs a different, more targeted approach. Understanding the specific tools available under Japanese law for evidence gathering, both before and during litigation, is essential for any company involved in IP disputes in Japan.

Unlike the extensive party-driven discovery common in the US, evidence gathering in Japanese IP litigation primarily relies on specific procedures outlined in the Code of Civil Procedure (民事訴訟法 - Minji Soshou Hou or "CCP") and supplemented by provisions within IP-specific statutes like the Patent Act (特許法 - Tokkyohou), Copyright Act (著作権法 - Chosakuken Hou), Trademark Act (商標法 - Shouhyou Hou), and Unfair Competition Prevention Act (不正競争防止法 - Fusei Kyousou Boushi Hou). Generally, the party asserting a fact bears the burden of proving it, making access to the opponent's information critical, yet subject to distinct rules and court oversight.

Pre-Litigation Evidence Gathering: Limited but Potent Tools

Japanese law offers limited avenues for formal evidence gathering before a lawsuit is filed. While some mechanisms exist on paper, their practical utility varies significantly.

- Evidence Preservation (証拠保全 - Shouko Hozen; CCP Art. 234): This is arguably the most powerful and practically utilized pre-litigation tool, especially in patent and trade secret cases.

- Purpose: Officially, its purpose is to secure evidence that might be lost, destroyed, or altered before it can be formally examined during litigation. The requesting party must make a preliminary showing (sosomei) that such circumstances exist making future use of the evidence difficult.

- Practical Use (De Facto Discovery): In practice, evidence preservation is frequently used as a form of pre-suit discovery (証拠開示的運用 - shouko kaiji-teki unyou). It allows a party, upon court order, to conduct an early inspection of the opposing party's premises (e.g., factories, laboratories), documents, or machinery before the opponent has a chance to conceal or modify evidence after being notified of a lawsuit. This is particularly valuable for observing manufacturing processes, examining infringing devices, or securing critical internal documents.

- Procedure: The request is typically filed ex parte (without initially notifying the opposing party). If the court grants the order, a judge, court clerk, and often a technical advisor or expert will visit the specified location to conduct the examination. The element of surprise is key to its effectiveness in preventing spoliation. The respondent is obligated to cooperate.

- Requirements: The applicant must demonstrate a prima facie case of infringement and the necessity of preserving the specific evidence due to the risk of it becoming unusable later. While the rules require showing this necessity, courts in practice sometimes apply this standard flexibly, recognizing the strategic value in securing evidence early, especially when dealing with internal processes or easily modifiable information.

- Impact: A successful evidence preservation action can yield crucial evidence (inspection reports, photographs, document copies) that forms the backbone of a subsequent infringement lawsuit. Refusal to comply can lead to adverse inferences by the court.

- Other Pre-Litigation Mechanisms (Limited Practical Use):

- Pre-Action Notice System (提訴予告通知制度 - Teiso Yokoku Tsuchi Seido; CCP Art. 132-2): This system allows a potential plaintiff to send a formal notice of intent to sue, which theoretically triggers certain limited information exchange obligations. However, it requires significant detail in the notice and lacks strong enforcement mechanisms if the recipient refuses to cooperate. Consequently, it is reported to be very rarely used in practice.

- Bailiff's On-site Inspection (執行官による現況調査 - Shikkoukan ni yoru Genkyou Chousa; CCP Art. 132-4): Following a pre-action notice, a party can request a court bailiff to conduct an inspection of the current state of physical objects or premises. Again, due to procedural complexities and limited scope, this tool sees little practical application.

Given the limitations of other pre-suit options, evidence preservation remains the primary strategic tool for plaintiffs needing to secure evidence held by the defendant before initiating formal litigation in Japan.

Evidence Gathering During Litigation

Once a lawsuit is filed, a broader range of court-supervised evidence gathering procedures become available:

- Document Production Orders (文書提出命令 - Bunsho Teishutsu Meirei; CCP Art. 220 et seq., Patent Act Art. 105, etc.): This is a cornerstone of evidence gathering during litigation, analogous in purpose, though not scope, to document requests in US discovery.

- Obligation: Parties generally have an obligation to produce documents relevant to proving asserted facts when ordered by the court.

- Procedure: A party requests the court to order the opposing party (or a third party) to produce specifically identified documents. The request must explain the document's relevance, the fact it aims to prove, and why the holder is obligated to produce it.

- Exceptions: The obligation is not absolute. Article 220 of the CCP lists several exceptions, including documents related to trade secrets (unless production is necessary for proving infringement or damages – a key battleground in IP cases), documents prepared solely for the holder's internal use, and documents subject to professional privilege. Patent Act Article 105 provides specific rules regarding trade secret exceptions in patent cases.

- Sanctions: If a party fails to comply with a production order without justification, the court may deem the requesting party's assertions about the document's contents to be true (CCP Art. 224).

- In Camera Review (秘密保持手続 - Himitsu Hoji Tetsuzuki or インカメラ手続 - Inkamera Tetsuzuki): To balance the need for evidence with the protection of confidential information, particularly trade secrets, courts can employ in camera procedures (e.g., Patent Act Art. 105-4). The court can order the document holder to present the document only to the judges, who review it privately to determine if an exception applies or if it's relevant to the case. The court may involve technical advisors in this private review. If production is ultimately ordered, the court can issue protective orders limiting access and use of the information (CCP Art. 132-2, Patent Act Art. 105-7).

- Court-Ordered Inspections (検証 - Kenshou; CCP Art. 232): The court can order and conduct inspections of places, objects, or persons relevant to the case. In IP litigation, this might involve inspecting an allegedly infringing factory, machinery, or product. Parties typically attend these inspections along with the judge(s) and often technical advisors.

- Expert Opinions (鑑定 - Kantei; CCP Art. 212 et seq.): The court may appoint neutral experts to provide opinions on technical or specialized issues beyond the judges' expertise. In IP cases, this frequently involves technical analysis for infringement (claim construction, comparison with accused product/process) or validity assessments, or economic analysis for damages. This differs from the US system where parties primarily rely on their own retained experts, although parties in Japan can also submit opinions from their own experts as documentary evidence.

- Calculation Expert System (計算鑑定人制度 - Keisan Kanteinin Seido; Patent Act Art. 105-2): Specific to patent infringement damages, this system allows the court, upon a party's motion, to appoint a neutral expert (typically a CPA) – a "calculation expert" – to audit the infringer's books and records necessary for calculating the damages (e.g., sales volume, profits). The alleged infringer is obligated to explain the necessary matters to the appointed expert. This provides a mechanism to access financial data crucial for applying damages provisions like Patent Act Article 102.

- Commissioning Examinations (調査嘱託 - Chousa Shokutaku; CCP Art. 186): The court can request public offices or other organizations (domestic or foreign) to conduct necessary examinations or report findings. This might be used, for example, to obtain specific public records.

- Party Interrogatories (当事者照会 - Toujisha Shoukai; CCP Art. 163): Parties can submit written questions to each other regarding matters necessary for preparing allegations or proof. While available, its effectiveness can be limited compared to US interrogatories, as the consequences for evasive or non-answers are less severe than for failing to comply with a court order like a document production order.

- Attorney Inquiry System (弁護士会照会 - Bengoshikai Shoukai; Attorney Act Art. 23-2): Although technically operating outside the direct court process, this system is a highly utilized practical tool. An attorney representing a party can request their local bar association to make inquiries to public entities or private organizations/companies to report on necessary matters.

- Utility: It can be effective for obtaining information from third parties (e.g., customer lists from distributors, financial information from banks, technical specifications from suppliers) who might be reluctant to cooperate voluntarily. Many companies and public bodies have established procedures for responding to these inquiries.

- Limitations: Response is not legally mandatory in the same way as a court order. Recipients can refuse to answer, often citing confidentiality obligations (e.g., personal information protection, contractual duties) or lack of relevance. The bar association reviews the request for appropriateness before issuing it, but the inquiry lacks the direct compulsive power of a court order. Success often depends on the recipient's willingness to cooperate and the clarity and justification of the request.

The Inspection System ("Sasho", 査証制度 - Sashou Seido; Patent Act Art. 105-2 etc.)

Introduced by the 2019 Patent Act amendments (effective 2020), the sasho system is a relatively new and potentially significant tool, inspired by European inspection procedures.

- Purpose: To address difficulties in proving infringement, particularly for process patents or internally used devices, where evidence resides solely within the alleged infringer's premises.

- Procedure: After a lawsuit has been filed, a party can petition the court to appoint a neutral technical expert (査証人 - sashounin) to conduct an on-site inspection (査証 - sashou) at the alleged infringer's facility (factory, office, laboratory, etc.).

- Requirements: The petitioner must establish a high probability of infringement and demonstrate that the inspection is necessary to prove the alleged infringement (i.e., the evidence cannot be reasonably obtained through other means like document production orders).

- Conduct: The court-appointed, impartial expert (often a patent attorney or academic with relevant technical expertise) enters the premises and conducts the inspection according to the court's order. This may involve observing processes, operating machinery, taking measurements, examining documents directly related to the technical aspects of infringement, and asking questions. The expert is bound by confidentiality obligations.

- Outcome: The expert prepares a report detailing their findings and submits it to the court. Parties typically receive a copy and can use it as evidence.

- Sanctions: If the alleged infringer obstructs the inspection without justifiable reason, the court may find the petitioner's assertions regarding the infringement based on the intended inspection to be true (Patent Act Art. 105-2(5)).

- Key Differences: Unlike pre-litigation evidence preservation (shouko hozen), sasho can only be initiated after filing suit. Compared to German Besichtigung, the Japanese system uses a neutral technical expert appointed by the court, rather than potentially involving bailiffs directly in the technical assessment.

- Practical Application: Being relatively new, the full extent of sasho's practical application and judicial interpretation is still developing. Its effectiveness will depend on how courts balance the need for evidence with concerns about disrupting business operations and protecting trade secrets beyond those directly relevant to infringement. However, it offers a potentially powerful tool, especially where infringement is difficult to prove through documents alone.

Protecting Confidential Information

Japanese procedures recognize the need to protect sensitive business information during evidence gathering. As mentioned, in camera reviews allow judges (and potentially experts bound by confidentiality) to assess the relevance and necessity of producing potentially sensitive documents before exposing them to the opposing party. Furthermore, courts can issue protective orders (秘密保持命令 - himitsu hoji meirei, e.g., Patent Act Art. 105-4) restricting access to disclosed trade secrets to specific individuals (e.g., attorneys, designated in-house counsel, experts) and prohibiting their use outside the litigation, with significant penalties for violations.

Strategic Considerations and Comparison with US Discovery

The Japanese system for evidence gathering differs markedly from US discovery:

- Scope: Japanese procedures are generally more targeted and less expansive than broad US discovery requests (e.g., depositions are not a standard feature, document requests must be reasonably specific).

- Court Involvement: The court plays a much more central role in ordering and supervising evidence gathering in Japan.

- Pre-Trial Phase: There is no distinct, extensive pre-trial discovery phase comparable to the US system; evidence gathering occurs alongside the main court proceedings.

- Emphasis on Specificity: Requests for evidence, particularly document production orders, generally require greater specificity regarding the documents sought and their relevance compared to initial US discovery requests.

Strategic Implications:

- Early Assessment: Parties need to conduct thorough early case assessments to identify the key evidence required and anticipate what evidence the opponent possesses.

- Targeted Use of Tools: Success relies on strategically employing the available mechanisms. Pre-litigation evidence preservation (shouko hozen) can be crucial for securing volatile evidence. During litigation, well-formulated, specific document production requests, potentially combined with court inspections (kenshou) or the new sasho procedure, are key.

- Anticipation: Parties must anticipate the opponent's likely evidence gathering tactics, including potential shouko hozen requests early in the dispute (even before formal filing).

- Confidentiality: Proactively identifying trade secrets and utilizing protective order mechanisms is essential when compelled to produce sensitive information.

Conclusion

While Japan lacks the broad, party-driven discovery familiar in the US, its legal system provides a distinct set of tools for evidence gathering in IP litigation. Procedures like evidence preservation (shouko hozen), document production orders (often involving in camera review), court inspections (kenshou), and the newer expert-led inspection system (sashou seido) offer mechanisms to obtain necessary information, albeit often requiring specific justification and direct court involvement. Success in Japanese IP litigation demands a thorough understanding of these procedures, their limitations, and their strategic application within the framework of the Japanese Code of Civil Procedure and specific IP laws. Effective planning and targeted use of these tools are crucial for building a compelling case.

- Calculating Patent Infringement Damages in Japan: Stacking Royalties on Rebutted Profits?

- Protecting Innovation: Patent Enforcement and Management Strategies in Japan

- Protecting the Edge: Japan's Evolving Export Controls and New Patent Secrecy Regime for Technology Companies

- Supreme Court of Japan – 最高裁判所