Gathering Proof in Japanese IP Litigation: Tools, Trade-Secret Safeguards & Court Tactics

TL;DR

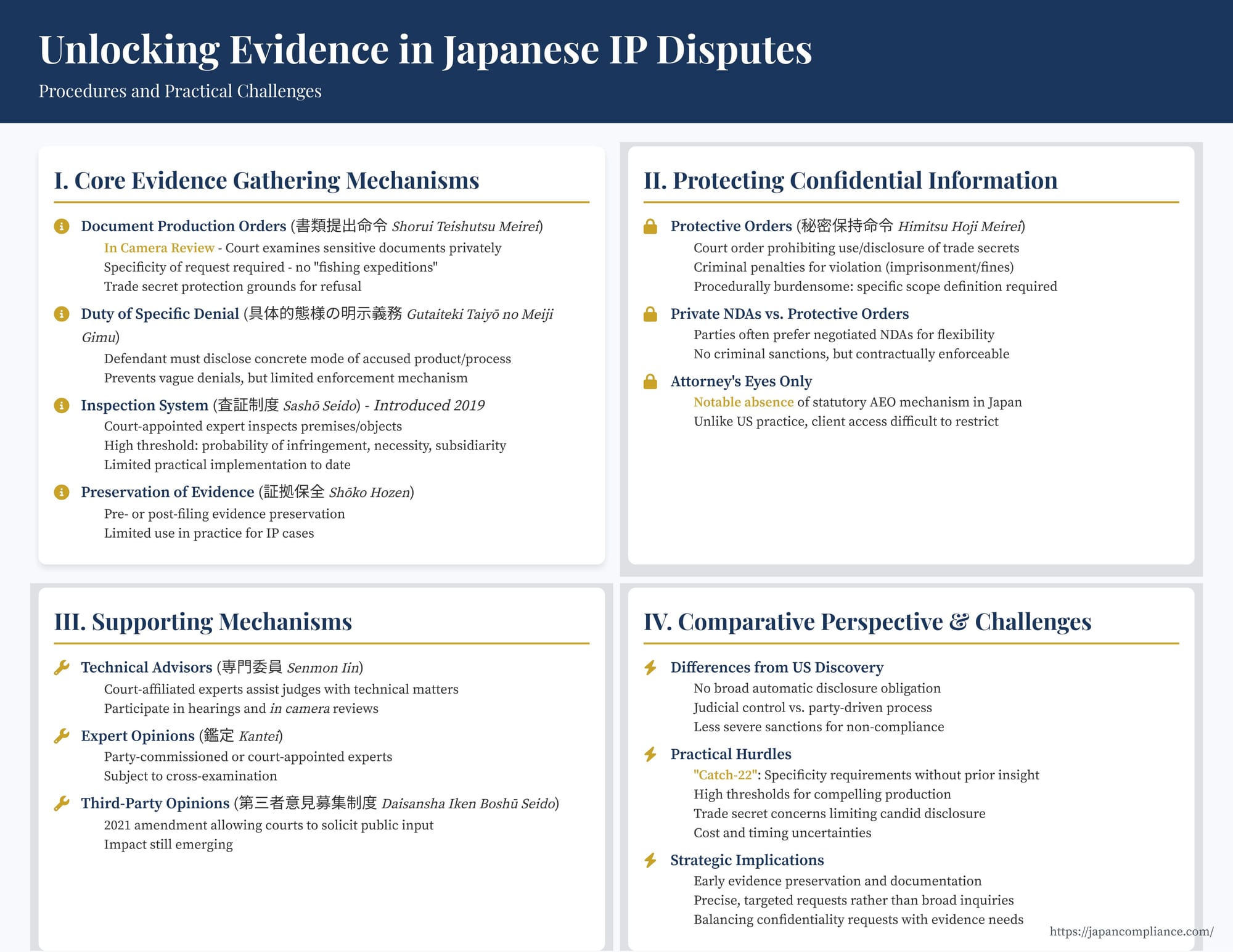

Japanese IP litigation lacks U.S.-style discovery, but rights-holders can compel proof through document-production orders, in-camera reviews, a high-threshold inspection system, and protective orders—yet trade-secret concerns and judicial gatekeeping still make evidence hard to unlock.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Evidence Conundrum in IP Litigation

- Core Evidence-Gathering Mechanisms in Japanese Civil IP Litigation

- Document Production Orders

- Duty of Specific Denial

- Inspection System (Sashō)

- Preservation of Evidence

- Pre-Action Disclosure Mechanisms

- Protecting Confidential Information

- Protective Orders

- Practical Realities: NDAs vs. Protective Orders

- Attorney’s Eyes Only (AEO) Gap

- Supporting Mechanisms

- Comparative Perspective and Challenges

- Conclusion: A System of Incremental Adaptation

Introduction: The Evidence Conundrum in IP Litigation

Securing adequate evidence is fundamental to success in any litigation, but intellectual property (IP) disputes often present unique hurdles. Infringement activities, particularly concerning process patents or internal B2B operations, frequently occur behind closed doors, leaving the rights holder with limited direct proof. The crucial evidence needed to establish infringement or quantify damages often lies predominantly, if not exclusively, in the hands of the alleged infringer.

This information asymmetry poses a significant challenge for IP enforcement globally. While the United States employs a broad pre-trial discovery system allowing parties extensive access to the opposing side's documents and information, Japan, like many civil law jurisdictions, adopts a more constrained approach. There is no direct equivalent to US-style discovery. Instead, Japan relies on a set of specific procedural tools, primarily invoked after litigation has commenced, aimed at enabling parties to obtain necessary evidence under court supervision.

Over the past two decades, driven by Japan's national strategy to strengthen IP protection, these evidence-gathering mechanisms have undergone significant reforms. However, practical challenges remain. Understanding the available procedures, their limitations, and the strategic considerations involved is crucial for any party, particularly foreign entities, involved in IP litigation in Japan.

Core Evidence Gathering Mechanisms in Japanese Civil IP Litigation

Japanese law provides several tools for obtaining evidence during IP litigation, primarily centered around court orders for specific types of disclosure or investigation.

1. Document Production Orders (書類提出命令 - Shorui Teishutsu Meirei)

Governed by Article 105 of the Patent Act (with similar provisions in other IP laws) and Article 220 et seq. of the Code of Civil Procedure, this is the primary mechanism for compelling an opposing party (or sometimes a third party) to produce relevant documents.

- Scope: Initially limited, the scope was expanded by amendments in 1999 to explicitly include documents "necessary for proving the infringement" or "necessary for calculating the damages caused by the infringement" (Patent Act Art. 105(1)). This was a significant step intended to ease the rights holder's burden.

- Procedure: A party requests the court to order the holder of specific documents to produce them. The requesting party must demonstrate the necessity of the documents for proving their case and identify the documents with reasonable specificity. The document holder can refuse production based on legally prescribed grounds, most relevantly, if the document pertains to a trade secret (営業秘密 - eigyō himitsu) that is not covered by certain exceptions (Civil Procedure Act Art. 220(iv)(d); Patent Act Art. 105(1) proviso). Other grounds include self-use documents or documents related to professional secrets.

- In Camera Review (インカメラ手続 - In Kamera Tetsuzuki): A crucial element, introduced in 1999 and enhanced in 2004 and 2018, is the in camera procedure (Patent Act Art. 105(2)). If a party refuses production citing trade secrets, the court can order the documents submitted only to the court. The judges (sometimes with the assistance of technical advisors) review the documents ex parte to determine if a legitimate ground for refusal exists and, importantly since the 2018 amendments, to assess the necessity of the document for proving infringement or damages. This allows the court to balance the need for evidence against the need to protect secrets without prematurely disclosing sensitive information to the opposing party.

- Practical Realities: Despite these mechanisms, compelling document production against a resisting party remains challenging. Courts may interpret "necessity" strictly, and identifying documents with sufficient specificity can be difficult without prior knowledge. Furthermore, data indicates that formal document production orders compelling disclosure over objections are not frequently issued. Often, the mere filing of a motion for a document production order prompts the document holder to voluntarily submit redacted versions or relevant portions to avoid a formal order or extensive in camera proceedings. While in camera review usage has reportedly increased since the 2018 reforms enhancing its role in necessity assessment, concerns exist that courts might form preliminary views on the merits during this ex parte process, potentially disadvantaging the requesting party without a full hearing on the evidence.

- Sanctions: Failure to comply with a document production order without just cause can lead the court to deem the requesting party's assertions about the document's contents to be true (Civil Procedure Act Art. 224). However, unlike the severe sanctions possible in US discovery, direct penalties like fines or imprisonment for non-compliance by a party are generally not available in this context.

2. Duty of Specific Denial (具体的態様の明示義務 - Gutaiteki Taiyō no Meiji Gimu)

Introduced in the 1999 Patent Act amendments, Article 104-2 requires a defendant denying infringement to specifically disclose the concrete mode (gutaiteki taiyō) of their own accused product or process. The intent was to prevent vague denials and force the alleged infringer to provide specific information about their activities, thereby aiding the patentee in identifying differences or confirming infringement.

In practice, while this provision encourages defendants to be more forthcoming than they might otherwise be, its effectiveness can be limited. Defendants may provide descriptions that patentees still view as insufficient or inaccurate. There are no direct sanctions for non-compliance, although a failure to provide specifics might negatively influence the court's overall impression or potentially strengthen the grounds for a subsequent document production order regarding the defendant's activities. Some practitioners feel it functions relatively well as a tool to frame the dispute, but it's not a substitute for obtaining direct evidence.

3. Inspection System (査証制度 - Sashō Seido)

The most significant recent addition is the sashō system, introduced by the 2019 Patent Act amendments (Article 105-2) and inspired partly by European, particularly German, inspection procedures. This system allows the court, upon a party's petition, to appoint a neutral expert inspector (sashō-nin) to enter the premises of the opposing party (or third parties) to inspect objects, conduct experiments, take measurements, or question individuals about facts necessary to prove infringement.

- Requirements: The threshold for obtaining an inspection order is high. The petitioner must demonstrate:

- A high probability (gaizensei) of infringement.

- Necessity of the inspection to prove infringement.

- Subsidiarity – that evidence cannot be reasonably obtained through other means (like document production orders).

- Proportionality – the burden on the inspected party is not unreasonable compared to the petitioner's need.

- Procedure: If granted, the court appoints an inspector (often a patent attorney or other technical expert). The inspection is conducted with notice to the inspected party (unlike surprise saisie raids). The inspector prepares a report detailing their findings, which is submitted to the court. The inspected party has an opportunity to review the report and request redactions of trade secrets before it is served on the petitioning party. The court rules on these redaction requests, potentially using in camera procedures.

- Sanctions: The inspected party has a duty to cooperate (Art. 105-2(4)). Refusal to grant access or obstruction can lead the court to deem the petitioner's assertions regarding the facts sought to be proven by the inspection as true (Art. 105-2-5).

- Current Status: This procedure was introduced as a potentially powerful tool, a "sword of last resort" (denka no hōtō). However, as of early 2025, there are no publicly reported cases where an inspection order has actually been granted and executed. The high threshold requirements, the availability of alternative (though perhaps less effective) means like document production orders, and potential concerns about protecting trade secrets during invasive inspections may contribute to its limited use thus far. Its practical impact remains to be seen.

4. Preservation of Evidence (証拠保全 - Shōko Hozen)

Japanese civil procedure allows for the preservation of evidence (Civil Procedure Act Art. 234 et seq.) either before or after filing a lawsuit. This procedure allows a party demonstrating a need to preserve specific evidence (e.g., physical objects, documents, status of machinery) that might otherwise be lost or altered to petition the court. If granted, the court can conduct an inspection, order document production, or examine witnesses to preserve the evidence for later use in litigation.

While potentially useful, its application in complex IP cases faces hurdles. Courts require a strong showing that the evidence is likely to be altered or destroyed and may be reluctant to grant orders perceived as overly broad or exploratory, especially pre-suit. Compared to post-filing mechanisms like document production or inspection orders under the Patent Act, its utility for uncovering unknown evidence (as opposed to preserving known evidence) in typical IP infringement scenarios appears limited, and its use in IP cases is reportedly infrequent.

5. Pre-Action Disclosure Mechanisms (訴え提起前の照会等 - Uttae Teiki Mae no Shōkai Tō)

The 2003 Code of Civil Procedure amendments introduced tools for pre-action inquiries (Art. 132-2) and evidence collection (Art. 132-4). These allow a party contemplating litigation to send inquiries to the prospective defendant or petition the court to collect specific evidence before filing suit. However, these mechanisms require prior notification to the potential defendant and provide broad grounds for refusal (including protection of trade secrets or privacy), and critically, lack any real compulsion or sanctions for non-response. Consequently, they are rarely used in practice, especially in contentious IP matters where voluntary cooperation is unlikely.

Protecting Confidential Information

A major tension in evidence gathering is protecting sensitive business information, particularly trade secrets, from disclosure to competitors. Japanese procedures incorporate several safeguards.

Protective Orders (秘密保持命令 - Himitsu Hoji Meirei)

Introduced in the 2004 Patent Act amendments (Art. 105-4), protective orders are the primary statutory tool for protecting trade secrets disclosed during litigation (primarily through document production or inspection reports).

- Mechanism: Upon motion by a party demonstrating that disclosed evidence contains their trade secrets crucial for their business, the court can issue an order prohibiting the receiving party (including their employees, lawyers, and experts) from using the secrets outside the litigation or disclosing them to anyone not named in the order.

- Scope: The order specifies the individuals bound and the scope of the protected information.

- Sanctions: Violation of a protective order carries potentially severe criminal penalties (imprisonment and/or fines, Art. 105-6 Patent Act; Art. 22 UCPA). This criminal sanction makes it a powerful, albeit burdensome, tool.

Practical Realities: NDAs vs. Protective Orders

Despite the availability of statutory protective orders, parties in Japanese IP litigation often prefer to manage confidentiality through privately negotiated Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs) or confidentiality agreements specific to the litigation.

- Reasons for Preference: Protective orders, while carrying strong sanctions, can be seen as inflexible and procedurally burdensome. Defining the exact scope of protected secrets and the individuals covered requires court intervention. Modifying the order later also requires court approval. NDAs, conversely, offer greater flexibility for parties to tailor the terms, define confidentiality levels, specify permitted uses, and agree on handling procedures without direct court oversight for every step. The perceived burdens of managing information under a formal court order, coupled with the severe potential penalties for accidental violation, often lead parties (and their counsel) to favour contractual solutions where possible.

- Limitations: Of course, NDAs lack the direct criminal sanctions of a protective order; enforcement relies on breach of contract claims.

Attorney's Eyes Only (AEO)

A common feature in US litigation, particularly IP cases involving highly sensitive technical or commercial secrets, is the "Attorney's Eyes Only" designation within protective orders. This restricts access to the most sensitive documents solely to the opposing party's outside legal counsel and potentially independent experts, excluding the client's own personnel (including in-house counsel in some cases).

Japan currently does not have a statutory AEO mechanism. While protective orders exist, they do not typically differentiate access levels to exclude the client entirely. The potential introduction of an AEO-like system has been discussed as a way to further encourage disclosure of highly sensitive information by mitigating the risk of direct exposure to a business competitor, but it has not been implemented. This remains a key difference from US practice and a potential area for future consideration if existing measures are deemed insufficient to facilitate necessary evidence disclosure.

Supporting Mechanisms

Beyond direct evidence gathering tools, other procedural elements support the process.

- Role of Experts: Given the technical complexity of many IP cases, experts play crucial roles.

- Technical Advisors (専門委員 - Senmon Iin): As mentioned, these court-affiliated, part-time experts (often academics or researchers) assist judges by explaining technical concepts and clarifying issues based on their specialized knowledge (Civil Procedure Act Art. 92-2). They participate in hearings and in camera reviews but do not provide formal opinions on the ultimate legal or factual questions.

- Expert Opinions (鑑定 - Kantei): Parties can commission their own expert witnesses (kantei-nin) to provide written or oral opinions on technical matters, infringement analysis, or damages calculations. The court can also appoint an expert. These opinions are submitted as evidence and are subject to scrutiny and cross-examination.

- Third-Party Opinions (第三者意見募集制度 - Daisansha Iken Boshū Seido)

As noted earlier, the 2021 Patent Act amendment (Art. 105-2-11) allows courts in patent/utility model cases to solicit opinions from the public on significant issues affecting the case. While not direct evidence gathering, it allows the court access to broader perspectives on complex technical or legal points, potentially influencing its understanding of the evidence presented. Its practical impact is still emerging.

Comparative Perspective and Challenges

The Japanese system for evidence gathering in IP disputes reflects a balance characteristic of many civil law systems: prioritizing judicial control and protection against "fishing expeditions" over the broad party-driven discovery found in the US.

- Key Differences from US Discovery: The most significant difference is the lack of a broad, automatic obligation for parties to disclose all potentially relevant information early in the process. Japanese procedures are targeted – requiring identification of specific documents or information – and generally require demonstrating necessity to the court. Sanctions for non-compliance are also less severe overall compared to the potential consequences in US discovery.

- Challenges for Litigants (especially Foreign Parties):

- Accessing Proof: The primary challenge remains accessing sufficient evidence held by the opposing party, given the specific and targeted nature of the available tools and the hurdles in compelling production, particularly of confidential information.

- Specificity Requirement: Identifying documents with enough specificity to satisfy the requirements for a production order can be difficult without some initial insight, creating a "catch-22" situation.

- Cost and Efficiency: While potentially less expensive overall than full US discovery, pursuing multiple, targeted evidence requests (document production, inspection) can still be costly and time-consuming, with uncertain outcomes.

- Trade Secret Protection: While mechanisms exist, concerns about the adequacy of protection for highly sensitive trade secrets can make parties (both Japanese and foreign) hesitant to disclose information, even under protective orders, potentially hindering the fact-finding process.

Conclusion: A System of Incremental Adaptation

Japan's approach to evidence gathering in IP litigation has evolved significantly over the last twenty years, marked by incremental reforms aimed at strengthening enforcement capabilities while safeguarding confidential information. The introduction and refinement of document production orders, in camera reviews, protective orders, and the novel inspection system demonstrate a continuous effort to adapt civil procedure rules to the specific needs of IP disputes.

However, the system remains distinct from the broad discovery model of the US. It places greater emphasis on judicial supervision and requires parties seeking evidence to meet specific thresholds of necessity and relevance. While tools like the inspection system offer potentially powerful avenues, their practical effectiveness is still largely untested. Parties litigating IP rights in Japan must develop strategies tailored to this specific procedural landscape, understanding the strengths and limitations of each available mechanism and the critical importance of protecting confidential information throughout the process. Strategic planning, precise requests, and effective use of available procedures are key to successfully navigating the evidence-gathering phase of Japanese IP litigation.

- Protecting Innovation: Patent Enforcement and Management Strategies in Japan

- IP Management for Startups & Universities in Japan: Protecting and Leveraging Innovation

- Protecting the Edge: Japan's Evolving Export Controls and New Patent Secrecy Regime for Technology Companies

- Intellectual Property High Court (IPHC)