Unlawful Confinement and Extortion: A Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Decision on Connected Crimes

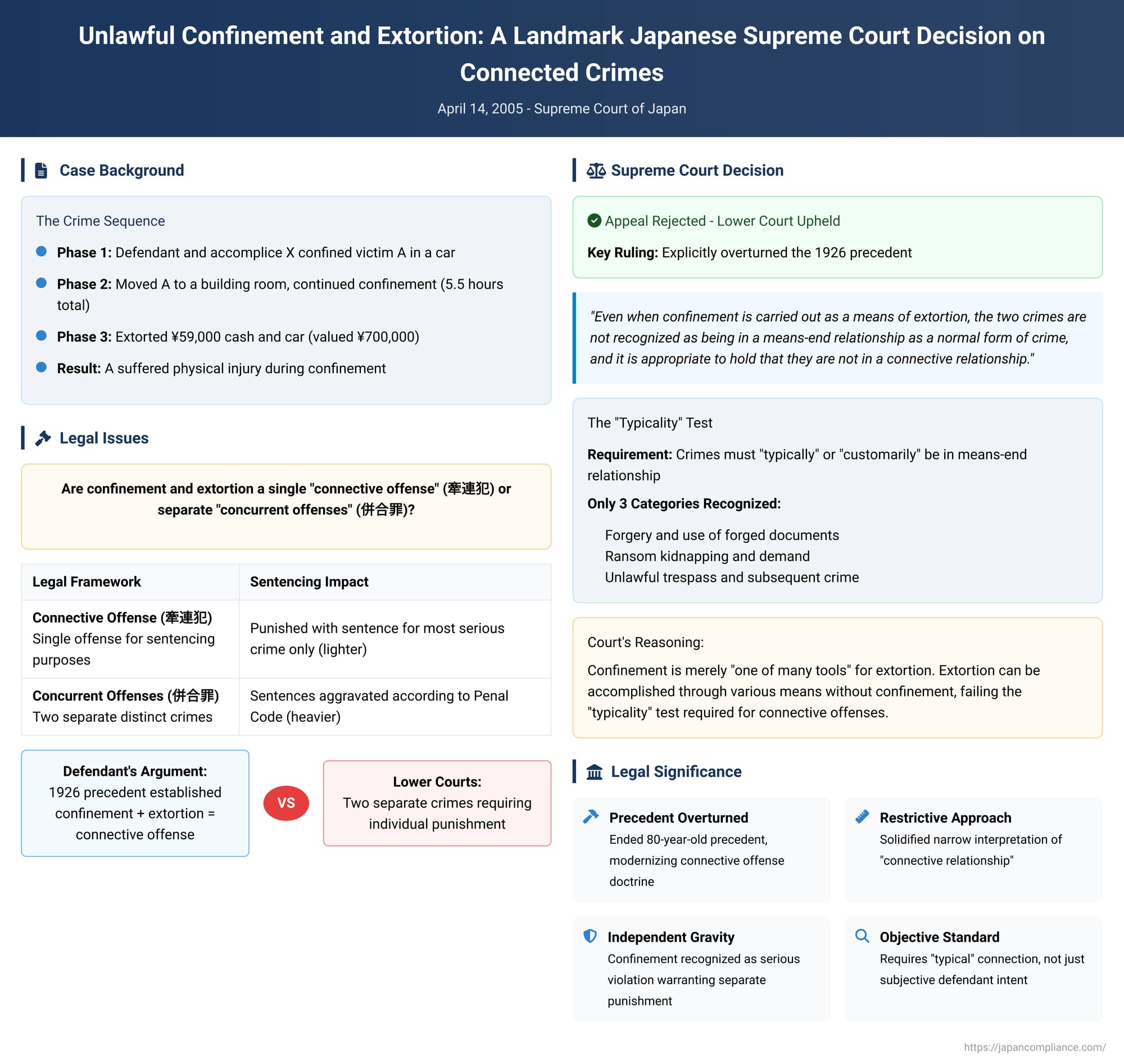

When a criminal act is committed as a stepping stone to another, does the law view it as a single, unified crime or as two separate offenses to be punished cumulatively? This fundamental question in criminal law was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on April 14, 2005. The case, involving unlawful confinement used as a means to commit extortion, saw the Court overturn a nearly 80-year-old precedent, thereby clarifying and narrowing the scope of what constitutes a "connective offense" (kenren-han) in Japanese law.

The ruling provides a crucial window into how the Japanese legal system distinguishes between a single criminal transaction and multiple, distinct crimes, a distinction with significant consequences for sentencing and criminal procedure.

Factual Background of the Case

The case involved a defendant who, in conspiracy with an accomplice, X, planned to extort money and valuables from a victim, A. The execution of their plan involved two distinct criminal components:

- Unlawful Confinement Causing Injury: Over a period of approximately five and a half hours, the defendant and his accomplice illegally confined A. The confinement took place in three phases: first in a car, then in a room in a building to which A was forcibly taken, and finally in the car again while being transported to the location where he would be released. During the initial confinement in the car, accomplice X assaulted A, causing physical injury.

- Extortion: While A was being held in the building, the perpetrators threatened the terrified victim, demanding money and property. Later, near the location where A was finally released, he was forced to hand over 59,000 yen in cash and a car (valued at approximately 700,000 yen).

The Osaka District Court found the defendant guilty of two separate crimes: unlawful confinement causing injury and extortion. It ruled that these were "concurrent offenses" (heigō-zai), and accordingly, the sentence was aggravated under the relevant provisions of the Penal Code. The defendant was sentenced to two years of penal servitude.

The Legal Journey and the Core Dispute

The defendant appealed, and the Osaka High Court upheld the original verdict. The case was then appealed to the Supreme Court on a specific point of law: the defendant argued that the lower courts' decision to treat confinement and extortion as separate, concurrent offenses directly contradicted a long-standing precedent from the Great Court of Cassation (the highest court in Japan before 1947). This precedent, a 1926 decision, had held that when confinement is used as a means for extortion, the two crimes are in a connective relationship (kenren-han) and should be treated as a single offense for sentencing purposes.

The Supreme Court was thus faced with a direct conflict between the lower court's modern interpretation and its own predecessor's nearly century-old ruling.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Overturning Precedent

The Supreme Court acknowledged the conflict. It recognized that the lower court's judgment, which treated the crimes as concurrent offenses, was indeed contrary to the 1926 precedent. However, instead of following the old precedent, the Court chose to explicitly overturn it.

In its judgment rejecting the appeal, the Court declared:

"Even when confinement is carried out as a means of extortion, the two crimes are not recognized as being in a means-end relationship as a normal form of crime, and it is appropriate to hold that they are not in a connective relationship."

With this single, powerful statement, the Court swept away the 1926 ruling and aligned the treatment of confinement and extortion with the stricter, more modern interpretation of "connective offenses."

Deep Dive: Understanding "Connective Offenses" in Japanese Law

To grasp the full significance of this ruling, it is essential to understand the Japanese legal concept of kenren-han and how it differs from heigō-zai.

- Concurrent Offenses (Heigō-zai): This is the default position for two or more separate crimes committed by the same person that have not yet been finalized by a court judgment. Each crime is viewed as distinct, and the overall sentence is typically increased (aggravated) according to rules laid out in the Penal Code.

- Connective Offense (Kenren-han): This is a special category under the broader heading of a "single offense for sentencing purposes" (kakei-jō ichizai). It applies when one crime is the "means" to another crime (the "end"), or when one crime is the "result" of another (the "cause"). When two crimes are deemed to be in this connective relationship, they are treated as a single offense, and the defendant is punished only with the sentence for the most serious of the crimes involved. This often results in a lighter sentence than if the crimes were treated as concurrent.

The Crucial Test: "Typical" Connectivity

Crucially, Japanese case law has established that for two crimes to be deemed a kenren-han, it is not enough that the defendant subjectively used one as a means for the other in a specific instance. There must be an objective connectivity: the two crimes must, by their very nature, "typically" or "customarily" be found in a means-end relationship. This "typicality" test is the cornerstone of the doctrine.

Over the decades, the Supreme Court has consistently narrowed the scope of what meets this test. In practice, only three main categories of crimes have been reliably recognized as forming a kenren-han:

- Forgery and Use: Forging a document (e.g., a check or contract) and then using that forged document.

- Ransom Kidnapping and Demand: Kidnapping a person for ransom and the subsequent act of demanding that ransom.

- Unlawful Trespass and the Subsequent Crime: Illegally entering a residence or building and then committing another crime inside, such as theft or assault.

In these classic examples, the first crime is almost inherently a preparatory step for the second. One rarely forges a document with no intention of using it, or trespasses into a home with no further criminal purpose.

Applying the Doctrine to Unlawful Confinement

This 2005 decision forced the Court to decide where the combination of confinement and extortion fit within this framework. In line with its restrictive trend, the Court concluded it did not belong in the same category as the classic examples.

The Court's logic, though not explicitly spelled out in the brief judgment, aligns with a consistent line of reasoning seen in other cases involving confinement:

- Confinement as "One of Many Tools": The Court has repeatedly held that when confinement is used to facilitate other crimes—such as assault, rape, murder, or robbery—it does not form a kenren-han. The reasoning is that confinement is merely one of many possible means to achieve those ends; it is not a necessary or typical precursor. An assailant can commit assault without first confining the victim.

- Confinement vs. Trespassing: The comparison with unlawful trespass is illuminating. Trespassing is given special status because it is almost always instrumental to a subsequent crime. Confinement, however, does not share this exclusively instrumental nature. It is entirely conceivable for confinement to be an end in itself—a crime committed for the purpose of holding someone captive, without any further goal of extortion or assault.

- Lack of "Typical" Connection to Extortion: Applying this logic, there is no inherent or typical reason why confinement should be the means for extortion. A person can be extorted through verbal threats, blackmail, or threats against family members, without being physically confined. Because confinement is just one of many options available to an extortionist, it fails the "typicality" test required for a kenren-han.

The 1926 precedent was based on an older, looser understanding of connectivity. The 2005 ruling decisively brought the law into a more consistent and logical state, holding that confinement, as a separate and significant violation of personal liberty, should be punished as a distinct crime, even when it facilitates another offense like extortion.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2005 decision was a significant act of judicial clarification. It formally ended an outdated precedent and solidified the modern, restrictive approach to the "connective offense" doctrine. The ruling establishes a clear principle: unless two crimes are so intrinsically linked by their nature that one is a typical means to the other, they are to be treated as separate offenses and punished accordingly. By separating unlawful confinement from extortion, the Court affirmed the independent gravity of each crime, ensuring that the full scope of a defendant's criminal conduct is reflected in the final judgment.