Unlawful Asset Freezes in Japan: Calculating Damages for Wrongful Provisional Attachments

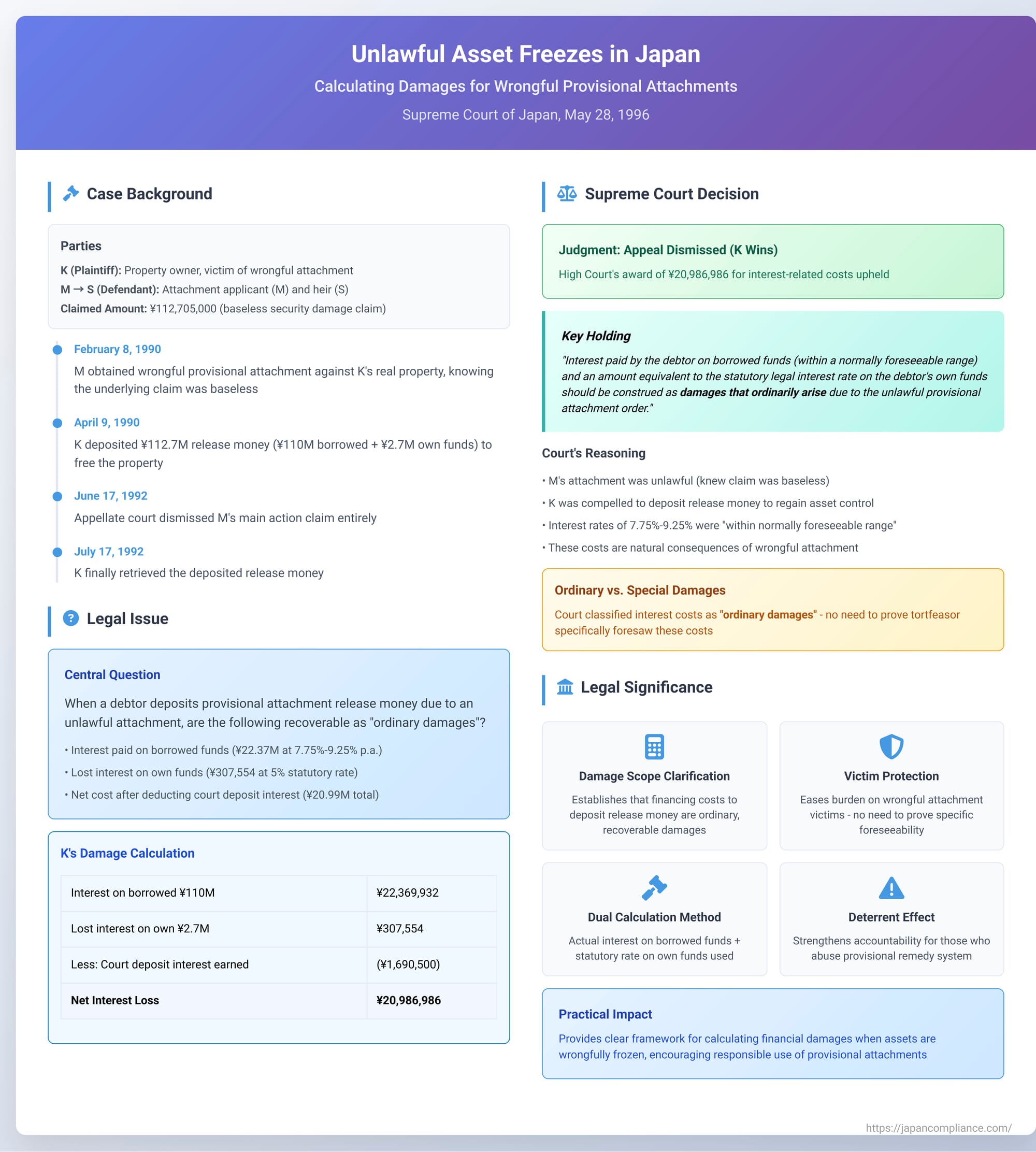

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of May 28, 1996 (Case No. 1995 (O) No. 531, Action for Damages)

When a business or individual has their assets wrongfully frozen through an unlawful provisional attachment (kari-sashiosae), the financial repercussions can be severe. This Japanese Supreme Court judgment from May 28, 1996, provides crucial clarification on the scope of damages recoverable by the victim, particularly concerning the costs incurred to free up those assets by depositing "provisional attachment release money" (kari-sashiosae kaihōkin).

I. Factual Background: A Contentious Path to Compensation

The case involved a plaintiff, K (an individual, the original debtor), who sought damages from S. S was the heir of M, who had initiated the provisional attachment that K alleged was unlawful. There was also a company involved, A M Co. Ltd., associated with K, against which an appeal was dismissed for procedural reasons; the core substantive ruling concerns K's claim.

The timeline and key events are as follows:

- The Wrongful Provisional Attachment: On February 8, 1990, M, the predecessor of S, applied for and obtained a provisional attachment order against real property owned by K. M's asserted claim was for JPY 112,705,000 in damages, allegedly arising from K's unauthorized sale of separate property that K had supposedly provided to M as security. Critically, the subsequent legal proceedings established that M knew this underlying claim (the "right to be preserved" by the attachment) did not actually exist at the time of application. This knowing pursuit of a baseless attachment was deemed a tort (an unlawful act, or fuhō kōi) against K.

- Securing Release of Assets: To lift the freeze on the real property, K took action. On April 9, 1990, K deposited the full amount specified in the attachment order as "provisional attachment release money" – JPY 112,705,000 – with the court. This deposit serves as substitute security for the claimant, allowing the actual attached property to be freed.

- Funding the Release Money: To raise this substantial sum, K:

- Borrowed JPY 110,000,000 from a credit union, incurring interest at rates between 7.75% and 9.25% per annum.

- Used JPY 2,705,000 of K's own funds.

- The Main Action and Subsequent Enforcement: M proceeded to file a lawsuit on the merits (hon'an soshō) against K based on the alleged JPY 112.7 million claim. Initially, M was successful in the first instance of this main action, obtaining a judgment with a declaration of provisional execution. Armed with this, M then took steps to enforce this judgment against the release money K had deposited, effectively trying to seize K's right to reclaim that deposit.

- K's Fightback: K was forced to apply for a stay of this enforcement and appealed the unfavorable judgment in the main action. K's efforts eventually paid off. On June 17, 1992, the appellate court in the main action overturned the initial decision and dismissed M's claim entirely. Despite this victory, K was unable to retrieve the deposited release money until July 17, 1992.

- The Damages Lawsuit: Following these events, K sued S (as M's heir) to recover the damages suffered due to M's wrongful provisional attachment. K's claim included several components:

- Attorney's fees incurred in objecting to the provisional attachment and defending the main action.

- Solatium (compensation for mental distress).

- The net financial cost of depositing the release money. This was calculated as:

- Interest paid on the JPY 110 million borrowed from the credit union: JPY 22,369,932.

- Lost interest on K's own JPY 2.705 million (calculated at the then-statutory civil legal interest rate of 5% per annum): JPY 307,554.

- From the sum of these two amounts, K deducted the minor interest earned on the JPY 112.7 million while it was deposited with the court (JPY 1,690,500).

- The net amount claimed for these interest-related costs was JPY 20,986,986.

The Osaka District Court and subsequently the Osaka High Court largely found in favor of K, awarding these damages. S appealed to the Supreme Court, but the appeal was specifically limited to the question of whether these interest-related costs (the JPY 20.986 million) were legally recoverable.

II. The Legal Issue Before the Supreme Court

The narrow but significant issue before the Supreme Court was:

When a debtor is forced to deposit provisional attachment release money due to an unlawful attachment that constitutes a tort, are the following costs recoverable as damages?

- Interest paid on funds borrowed from a financial institution to make up the release money.

- An amount equivalent to lost interest (at the statutory rate) on the debtor's own personal funds used for the release money.

Specifically, are these types of financial outlays considered "ordinary damages" (tsūjō songai) that the tortfeasor is liable for?

III. The Supreme Court's Judgment (May 28, 1996)

- A. Operative Part (The Court's Decision):

The Supreme Court dismissed S's appeal concerning K's claim. (The appeal concerning A M Co. Ltd. was dismissed on procedural grounds as S had failed to state any reasons for appeal against the company). This meant the High Court's decision awarding K the JPY 20,986,986 for interest-related costs was upheld. - B. The Court's Reasoning:The Supreme Court laid down a clear principle:"Where the application for and execution of a provisional attachment order on real property is unlawful because the right to be preserved did not exist from the outset, and thus constitutes a tort against the debtor, and where the debtor, in order to seek cancellation of that execution by depositing provisional attachment release money, is compelled to borrow funds from a financial institution or to use their own funds for this purpose, the interest paid by the debtor on such borrowed funds (within a normally foreseeable range) during the period the release money is deposited, and an amount equivalent to the statutory legal interest rate on the debtor's said own funds, should be construed as damages that ordinarily arise (tsūjō shōzu beki songai) for the debtor due to the said unlawful provisional attachment order."Applying this principle to the facts:The Supreme Court concluded that, under these circumstances, this JPY 20,986,986 sum indeed constituted damages that ordinarily arise from M's unlawful provisional attachment. The High Court's judgment was therefore affirmed as correct in its reasoning and conclusion. S's arguments to the contrary, characterized by the Court as merely advancing a unique personal view, were rejected.

- The Court acknowledged that M's provisional attachment was indeed unlawful and a tort because M knew the underlying claim was baseless.

- K was compelled to deposit the release money (JPY 112,705,000) from April 9, 1990, to July 17, 1992, to nullify the attachment's execution.

- K borrowed JPY 110 million from the credit union and paid JPY 22,369,932 in interest at rates of 7.75% to 9.25% per annum. The Court found these interest rates to be "within a normally foreseeable range."

- K used JPY 2,705,000 of personal funds, and the statutory interest (5% p.a.) on this sum for the period amounted to JPY 307,554.

- After deducting the JPY 1,690,500 interest earned on the court deposit, the net loss was JPY 20,986,986.

IV. Analysis and Implications

This judgment provides significant clarity on the scope of recoverable damages in cases of wrongful provisional attachments.

- A. "Ordinary Damages" vs. "Special Damages" in Japanese Tort LawJapanese law, when determining the extent of damages for torts (and by analogy from contract law, Article 416 of the Civil Code), distinguishes between:This Supreme Court decision is important because it categorizes the interest costs associated with depositing release money (both for borrowed funds and the opportunity cost of using one's own funds) as ordinary damages. This significantly eases the burden for victims of wrongful attachments. They do not need to undertake the often difficult task of proving that the person who wrongfully attached their assets specifically foresaw that these financing costs would be incurred. The Court deems these costs a natural and typical consequence.

- Ordinary Damages (tsūjō songai): These are damages that would normally, objectively, and typically arise from the type of unlawful act committed. The plaintiff does not need to prove that the tortfeasor specifically foresaw these damages.

- Special Damages (tokubetsu no jijō ni yotte shōjita songai or tokubetsu songai): These are damages that arise due to special or particular circumstances in the plaintiff's situation. For special damages to be recoverable, the plaintiff must generally prove that the tortfeasor foresaw, or reasonably could have foreseen, that these particular damages would occur.

- B. The Rationale: Why Compensate These Interest Costs?The legal framework for provisional attachment allows a debtor to deposit "release money" to free up the specifically attached asset (e.g., real estate, bank accounts). While the debtor's property itself might not be immediately sold off under a provisional attachment (unlike a final execution), its utility is severely hampered. It cannot be freely sold, used as collateral for new loans, or otherwise productively employed. Business operations can be crippled, and creditworthiness can be damaged.Therefore, a debtor often has a compelling need to deposit the release money to regain control of their assets and mitigate these ongoing harms. The Supreme Court recognizes that borrowing funds or using one's existing capital are standard and foreseeable methods for a debtor to come up with this release money. The interest paid on such loans, or the income lost from not being able to use one's own capital for other productive purposes, are direct financial consequences of the unlawful attachment. The commentary surrounding this case notes that the act of depositing release money is not considered an "unforeseeable" or "special" action by the debtor but a normal response to an attachment.

- C. Calculating the Damages: A Two-Pronged ApproachThe judgment implicitly endorses the methods used by the lower courts for calculating these interest-related damages:

- For Borrowed Funds (Positive Damage – sekkyoku songai):

The actual, documented interest paid by the victim (K) on the loan taken to fund the release money is recoverable. The key proviso added by the Supreme Court is that the interest rate on the loan must be "within a normally foreseeable range". This prevents a tortfeasor from being held liable for excessively high interest rates that the victim might have agreed to if those rates were commercially unreasonable or unusual. In this case, 7.75% to 9.25% p.a. was deemed foreseeable. - For Victim's Own Funds Used (Lost Profit/Opportunity Cost – shōkyoku songai or ubeshi rieki):

When the victim uses their own capital, the damage is the lost opportunity to earn a return on those funds elsewhere. The Supreme Court upheld the calculation of this loss based on the statutory legal interest rate (which was 5% per annum under the Civil Code at the time of these events) applied to the amount of own funds used, for the duration they were tied up.

- For Borrowed Funds (Positive Damage – sekkyoku songai):

- D. The "Own Funds" Calculation: Pragmatism Over Precision?Legal commentary (without referring to the specific PDF provided) often discusses the nuance of calculating damages for the use of "own funds." While this judgment endorses the use of the statutory legal interest rate, some might argue that if a plaintiff could prove they were forced to, for example, break a term deposit that was yielding 8% or abandon a specific investment project expected to return 10%, their actual lost profit might be higher than the statutory 5%.The Supreme Court's approach offers a degree of predictability and simplifies proof. Claiming based on the statutory rate avoids complex and potentially speculative evidence about what alternative investments the plaintiff might have made. It provides a clear, albeit sometimes conservative, baseline for compensation.This situation is also distinct from cases involving direct default on a pre-existing monetary debt owed to the plaintiff. In such cases, Article 419 of the Civil Code directly mandates statutory interest for late payment. Here, the damage is the lost opportunity to use one's own capital productively because it was tied up in a court deposit due to a tort. While the outcome (application of statutory interest) might seem similar, the underlying legal character of the loss is different. The court's decision reflects a practical method to quantify this lost opportunity cost.

- E. Context with Other Wrongful Provisional Remedy Cases:This judgment complements others concerning wrongful provisional remedies. For instance, a previous notable Supreme Court case (from January 22, 1990, which was the subject of a prior analysis request) focused on determining when an applicant for a provisional disposition is deemed negligent. This current case (May 28, 1996) shifts the focus to the scope of damages once liability for a wrongful provisional remedy is established (here, M's liability was clear due to the knowledge of the non-existent claim, implying at least gross negligence or intent).Together, these decisions build a picture of how Japanese law attempts to provide recourse for those harmed by improperly obtained provisional court orders, addressing both the conditions for liability and the extent of compensation. It's also worth noting that the lower courts in K's case had awarded other common heads of damage for wrongful provisional measures, such as attorney's fees and solatium, although these were not the subject of the final appeal to the Supreme Court.

V. Conclusion: Protecting Victims from the Costs of Unlawful Asset Freezes

The Supreme Court's May 28, 1996, judgment is a significant affirmation for individuals and businesses whose assets are wrongfully encumbered by unlawful provisional attachments. By classifying the interest costs incurred in depositing release money—both actual interest on loans and imputed interest on personal funds—as "ordinary damages," the Court has made it easier for victims to obtain fair compensation.

This ruling underscores that the financial consequences of having to free up assets from an unlawful attachment are not remote or unforeseeable but are a direct and typical result of the tortfeasor's actions. It reinforces the principle that those who abuse the provisional remedy system by knowingly pursuing baseless claims will be held accountable for the tangible financial burdens they impose on their victims.