Unjust Enrichment from "Forgotten Shares": Valuation When Sold, a Japanese Supreme Court Decision

Judgment Date: March 8, 2007

Case: Unjust Enrichment Claim (Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench)

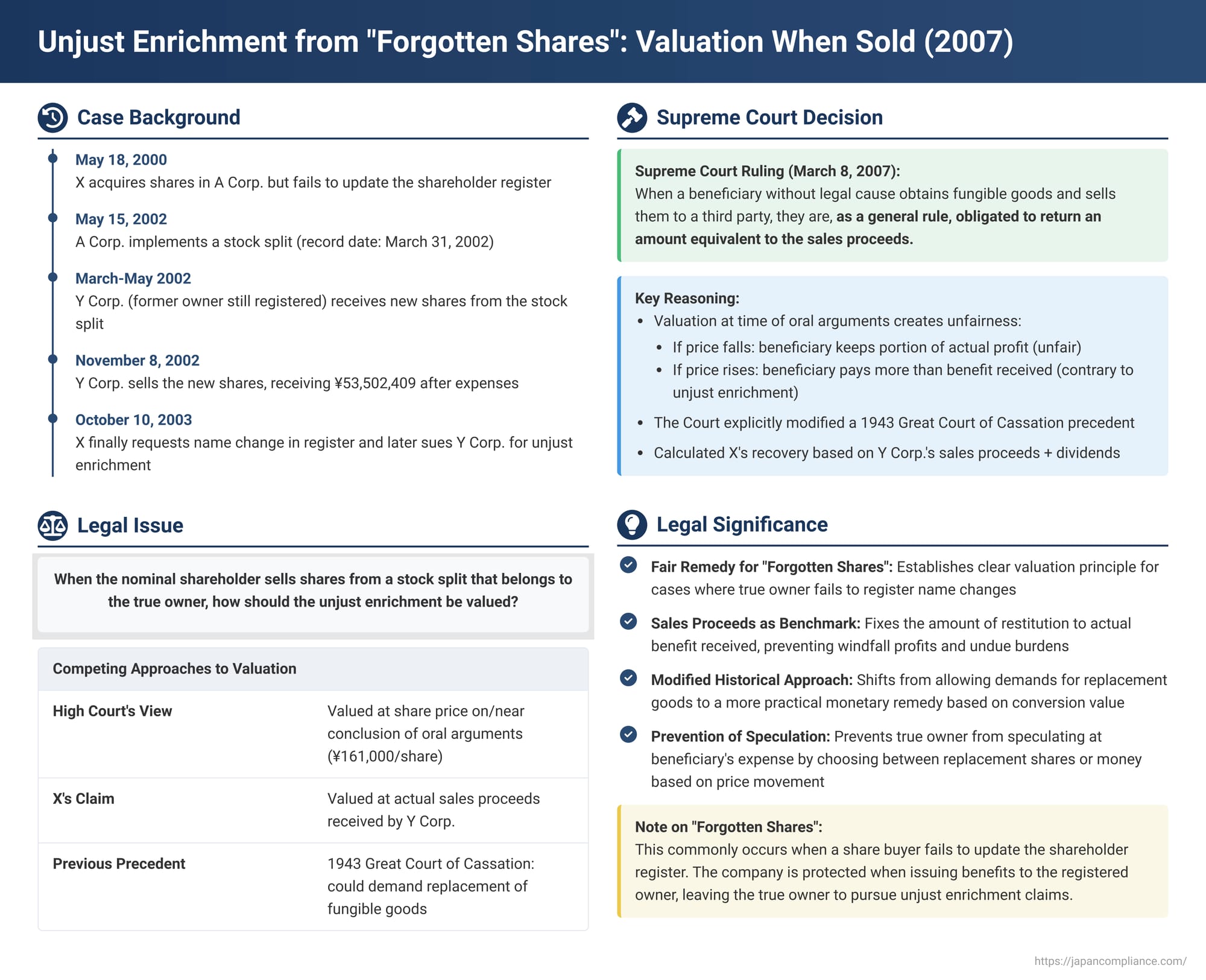

This Japanese Supreme Court case tackles a common problem arising from "forgotten shares"—shares where the true owner fails to register their name in the company's shareholder records. When benefits from these shares, such as new shares from a stock split, accrue to the person still listed on the register (the nominal owner), and that nominal owner subsequently sells these new shares, how should the amount of unjust enrichment owed to the true owner be calculated? The Court, in this decision, clarified the valuation method, prioritizing fairness and the actual benefit received by the nominal owner.

Factual Background: A Stock Split, Unregistered Shares, and a Subsequent Sale

The case involved X (appellants, two individuals who were the beneficial owners of shares), A Corp. (the company that issued the shares), and Y Corp. (appellee, the company erroneously listed as the shareholder).

- Share Acquisition and Failure to Register: On May 18, 2000, X acquired shares in A Corp., a publicly listed company (referred to as the "parent shares"). Although X received the share certificates from their securities company on October 31, 2000, they did not promptly undertake the necessary procedures to have their names replace the previous owner's name on A Corp.'s shareholder register (a process known as "meigi kakikai").

- Stock Split: On May 15, 2002, A Corp. implemented a stock split based on a record date of March 31, 2002.

- Erroneous Allotment to Y Corp.: Because X had failed to update the shareholder register, Y Corp., a previous owner of the parent shares, remained the shareholder of record on the critical date. Consequently, Y Corp., as the nominal shareholder, received the new shares generated by the stock split (the "new shares") and the corresponding share certificates.

- Dividends and Sale by Y Corp.: Y Corp. also received dividends amounting to JPY 14,235 (after tax) on these new shares. On November 8, 2002, Y Corp. sold the new shares to a third party, obtaining net proceeds of JPY 53,502,409 after deducting expenses.

- X's Claim: Around October 10, 2003, X finally requested A Corp. to register the transfer of the parent shares into their names. Subsequently, X sued Y Corp. based on the principle of unjust enrichment, seeking the return of the sales proceeds from the new shares and the dividends Y Corp. had received.

- Lower Court Rulings: The court of first instance and the original appellate court (High Court) held that Y Corp. had been unjustly enriched by receiving the new share certificates, the new shares themselves, and the dividends. They ruled that Y Corp. was obligated to return these benefits to X, and that X could claim the monetary value of the new shares instead of the return of the share certificates themselves. The High Court determined that, unless special circumstances dictated otherwise (i.e., valuing at the time of sale would be inequitable), the recoverable value of the new shares should be calculated based on their price at or near the conclusion of the oral arguments in the fact-finding instance. Finding no such special circumstances, the High Court used the closing price of A Corp.'s shares on May 17, 2005 (the day before oral arguments concluded), which was JPY 161,000 per share, to calculate X's recoverable amount for the shares at JPY 18,676,000 each.

- Appeal to Supreme Court: X, dissatisfied with this valuation, appealed to the Supreme Court. They argued that the recoverable amount for the new shares should be based on the actual sales proceeds Y Corp. had obtained.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Valuation Based on Sales Proceeds

The Supreme Court partially quashed the High Court's judgment and rendered its own, ultimately siding with X on the valuation principle.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- The Nature of Unjust Enrichment: The doctrine of unjust enrichment aims to rectify situations where a person's gain lacks legal justification, compelling the beneficiary to return the enrichment based on notions of fairness.

- Problems with Valuation at Oral Argument Conclusion for Sold Fungible Goods: The Court found the High Court's approach—valuing the restitution of sold fungible goods (like listed shares) at the time of the conclusion of oral arguments—to be problematic for two main reasons:

- If the price of the goods decreases after the sale: The beneficiary (Y Corp.) would be allowed to retain a portion of the sales proceeds, which the Court deemed unfair to the loser (X).

- If the price of the goods increases after the sale: The beneficiary would be burdened with a restitution obligation exceeding the benefit they actually retained. This, too, was considered unfair and inconsistent with the fundamental nature of unjust enrichment, which is to return the benefit received.

- The General Rule: Sales Proceeds: Consequently, the Supreme Court held that when a beneficiary, without legal cause, acquires fungible goods and subsequently sells them to a third party, they are, as a general rule, obligated to return to the loser an amount of money equivalent to the sales proceeds.

- Modification of Precedent: The Court explicitly stated that a Great Court of Cassation (Daishin-in) judgment from December 22, 1943 (Law Newspaper No. 4890, p. 3), should be modified to the extent that it conflicts with this newly articulated principle.

Applying this, the Supreme Court found no circumstances in this case that would warrant a departure from this general rule. It held that Y Corp. was obligated to return to X the total sum of the sales proceeds of the new shares and the dividends. The Court then recalculated the amounts due to each of the X appellants based on this principle.

Analysis and Implications: Navigating "Forgotten Shares" and Unjust Enrichment

This 2007 Supreme Court decision provides crucial clarification on handling unjust enrichment claims arising from "forgotten shares," particularly concerning the valuation of benefits that have been converted to cash.

1. The Perils of "Forgotten Shares" (Meigi Kakikai no Shitsunen)

Japanese company law requires a purchaser of shares (outside the book-entry system) to request a change of name in the shareholder register to be recognized by the company as a shareholder (Companies Act, Article 133(1)). When a shareholder, like X in this case, neglects this "meigi kakikai," several issues arise:

- Company's Reliance on the Register: Companies operate based on their shareholder register, especially when determining rights related to a specific "record date" (Companies Act, Article 124). For instance, Article 184(1) of the Companies Act specifies that shares resulting from a stock split are allotted to shareholders listed on the register as of the record date.

- Company's Exemption (Menseki): If a company distributes dividends or new shares (e.g., from a stock split) to the shareholder listed on the register, it is generally exempt from further liability to the true beneficial owner who failed to register. This "exempting effect" is vital for the smooth administration of corporate affairs. There is some academic debate on the precise scope of this effect for shares of non-share certificate issuing companies that are not on the book-entry system.

- Recourse for the Beneficial Owner: This leaves the beneficial owner (実質株主 - jisshitsu kabunushi) with a claim against the registered owner (名簿上の株主 - meibo-jō no kabunushi) who received the benefits. This type of situation, where benefits accrue to the registered owner due to the true owner's failure to update the register, is often referred to using the term "forgotten shares" (失念株 - shitsunen kabu).

- Book-Entry System Exception: It's important to note that the problem of "forgotten shares" in this context generally does not occur with shares managed under the book-entry transfer system, as name registration is handled collectively through "general shareholder notifications" rather than individual requests (Act on Book-Entry Transfer of Company Bonds, Shares, etc., Articles 151, 152).

2. Establishing the Registered Owner's Liability for Unjust Enrichment

While this Supreme Court case primarily focused on the amount of restitution, the underlying liability of the registered owner for unjust enrichment was already well-established.

- Precedent (1962 Supreme Court Case): A Supreme Court decision on April 20, 1962 (Minshu Vol. 16, No. 4, p. 860), had previously affirmed that when a registered owner received dividends and shares from a gratuitous share issuance (akin to a stock split), the beneficial owner could claim these benefits or their sale proceeds from the registered owner. This 1962 ruling was understood to extend to stock splits.

- Rationale for Liability: The justification is compelling:

- The company's ability to deal with the registered owner without liability (its exempting effect) serves administrative convenience in managing shareholder relations collectively; it does not mean the registered owner is the ultimate rightful owner of the economic benefits.

- The true right to receive such benefits lies with the beneficial owner.

- Furthermore, the price paid in a share transfer typically reflects the understanding that all subsequent shareholder rights and benefits pass to the transferee. Thus, any benefits the transferor (former owner still on the register) receives post-transfer are generally owed to the transferee.

- Distinction from Paid Acquisitions (1960 Supreme Court Case): A 1960 Supreme Court decision (Minshu Vol. 14, No. 11, p. 2146) had denied an unjust enrichment claim where the registered owner acquired shares for consideration (e.g., through a rights offering requiring payment). However, this distinction has been heavily criticized by legal scholars who argue that there's no strong reason to differentiate this from cases of gratuitous receipts like dividends or stock splits. The majority academic view now supports the beneficial owner's unjust enrichment claim even when the registered owner paid for the allotted shares, though the specifics of calculating the enrichment might differ.

3. The Core Issue: Valuing Unjust Enrichment for Sold Fungible Goods

The 2007 judgment's main contribution is its clear stance on valuation:

- Sales Proceeds as the General Rule: When a beneficiary (like Y Corp.) without legal cause obtains fungible goods (like listed shares) and then sells them, the amount to be returned to the loser (X) is, in principle, the sales proceeds.

- Fairness as the Guiding Principle: The Court’s reasoning is explicitly grounded in fairness:

- If valuation were at a later date (e.g., conclusion of oral arguments) and the market price had dropped, the beneficiary would unfairly retain a portion of the actual profit made from the sale.

- Conversely, if the market price had risen, the beneficiary would be penalized by having to pay more than the benefit actually obtained, which contravenes the essence of unjust enrichment (which is about returning the received benefit).

- Good Faith of Beneficiary: The judgment does not explicitly discuss whether Y Corp. was a good-faith or bad-faith beneficiary. However, prevailing academic opinion suggests that in "forgotten share" cases, the registered owner is often considered a good-faith beneficiary, as the situation arises from the beneficial owner's own omission. The Supreme Court likely proceeded on this assumption.

- Theoretical Basis: One way to understand this theoretically is that once Y Corp. sold the shares, its obligation to return the specific shares (which was impossible) converted into an obligation to return their value. This value became fixed at the moment of sale by the actual proceeds received, thereby severing the amount of enrichment from subsequent market fluctuations. A key practical reason is to prevent the registered owner's liability from changing due to market movements beyond their control, which is seen as equitable.

- Prioritizing "No Retained Profit for Beneficiary": The judgment appears to place greater emphasis on ensuring that the beneficiary (Y Corp.) does not retain any unearned profit, rather than on whether the loser (X) might end up in a slightly better position than if they had received the actual shares at a later date when the price might have been lower.

- "As a General Rule" - Acknowledging Exceptions: The Court's use of the phrase "as a general rule" when stating that sales proceeds are the measure of restitution indicates that exceptions are possible. For instance, if the unjustly obtained goods were sold at a price significantly below their objective market value without good reason, or if the beneficiary, through special skill or effort, managed to sell them at an exceptionally high price, the calculation might need adjustment.

4. No Obligation to Procure Replacement Fungible Goods

A significant implication of the Supreme Court's decision, particularly its modification of the 1943 precedent, is the rejection of the idea that the loser can demand the beneficiary procure and return identical replacement fungible goods.

- Lower Court's Approach vs. Supreme Court's Stance: The High Court in this case had suggested that X could choose between demanding the return of identical shares (valued at the time of oral argument conclusion) or their monetary value. The 1943 Great Court of Cassation decision, which this Supreme Court judgment modified, had overturned a lower court that awarded sales proceeds when replacement items were demanded, stating that replacement items should have been ordered.

- Preventing Speculation by the Loser: By fixing the restitution amount (in principle) to the sales proceeds, the Supreme Court prevents the loser from speculating at the beneficiary's expense. If the loser could choose, they would demand replacement shares if the market price rose after the sale, and demand cash (based on the higher of the sale price or a potentially inflated oral argument price under older interpretations) if the market price fell. This judgment curtails such opportunistic claims. The obligation is now primarily seen as a monetary one fixed at the time of conversion (sale).

Conclusion: Fairness in Rectifying Gains from "Forgotten Shares"

The Supreme Court's March 2007 decision brings greater clarity and fairness to the resolution of unjust enrichment claims arising from "forgotten shares." By establishing that the sales proceeds are generally the measure of restitution when wrongfully obtained fungible goods are sold, the Court ensures that the beneficiary does not retain profits they were not entitled to, nor are they unfairly penalized by market fluctuations occurring after they disposed of the asset. This ruling reinforces the equitable foundations of unjust enrichment law within the specific context of shareholding and corporate actions in Japan.