Unjust Enrichment from Condominium Common Areas: Who Has the Right to Sue? A 2015 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: September 18, 2015

Case Number: 2013 (Ju) No. 843 (Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench)

Introduction

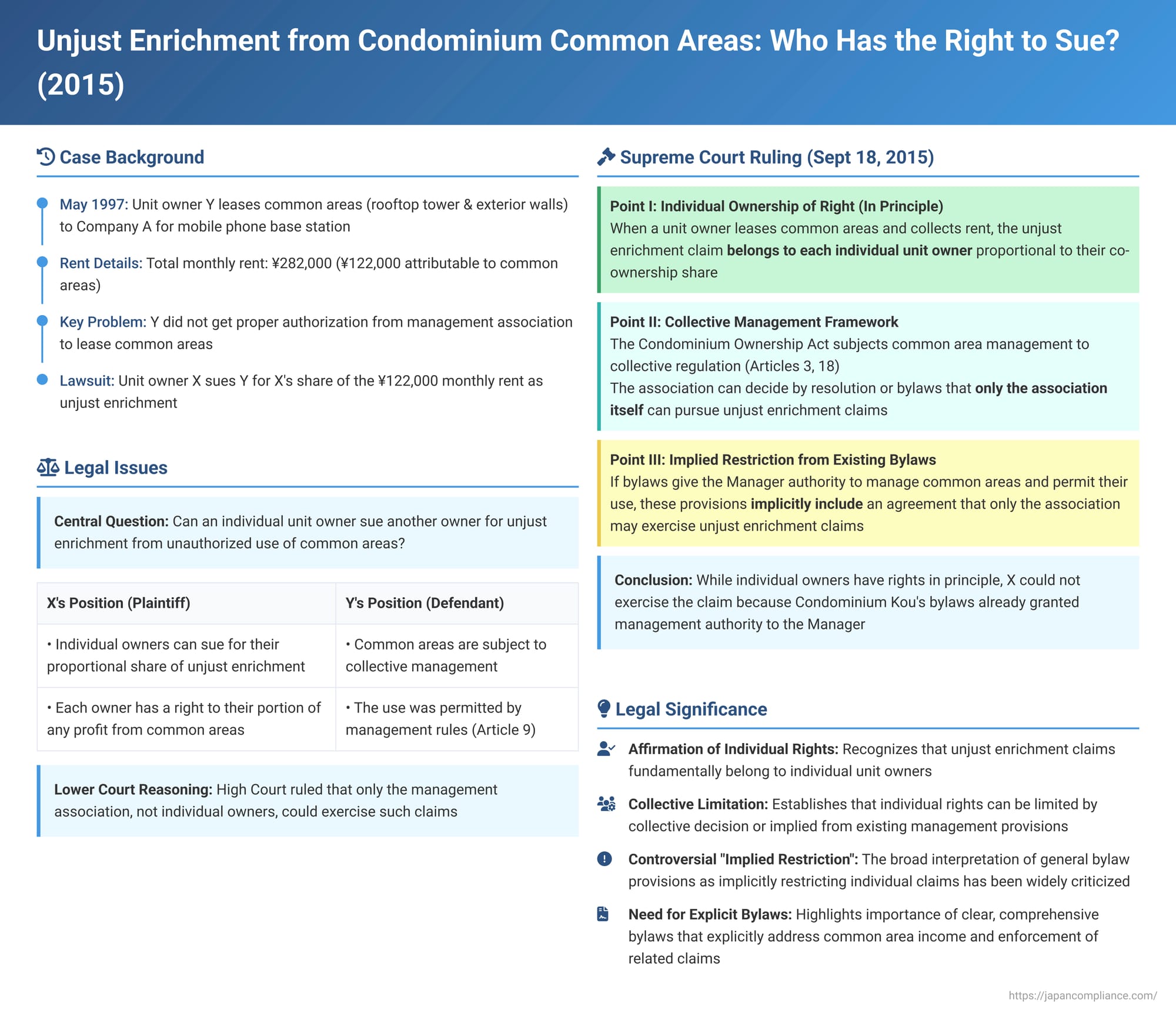

Condominiums, by their nature, involve a blend of private and shared spaces. While individual units are privately owned, common areas such as rooftops, exterior walls, lobbies, and grounds are co-owned by all unit owners. The use and management of these common areas can lead to complex legal questions, especially when they generate income or benefits for one owner to the exclusion of others. One such issue is whether an individual unit owner can sue another owner who has profited from using a common area without proper authorization, claiming a share of that profit as unjust enrichment.

A Japanese Supreme Court decision on September 18, 2015, provided crucial guidance on this matter. The case explored whether the right to claim unjust enrichment from the unauthorized rental of common areas belongs to individual unit owners or exclusively to the condominium's management association, and under what circumstances an individual owner can exercise such a right.

Facts of the Case

The dispute involved two unit owners in a condominium building located in Yokohama, referred to as "Condominium Kou."

The Lease of Common Areas:

Y, one of the unit owners in Condominium Kou, entered into a lease agreement in May 1997 with Company A, a mobile phone operator. Under this agreement, Y leased their privately-owned unit as well as portions of Condominium Kou's common areas – specifically, the rooftop tower (塔屋 - tōya) and exterior walls. The purpose of the lease was for Company A to install and operate a mobile phone base station. The equipment for controlling the antennas was placed in Y's private unit, while the antenna masts, cabling, and conduits were installed on the common areas.

The total monthly rent paid by Company A to Y was ¥282,000. It was determined that ¥122,000 of this monthly amount was attributable to the use of the common areas.

Condominium Kou's Management Rules (Bylaws):

The management rules of Condominium Kou contained several provisions relevant to the use of common areas:

- Article 9, Paragraph 1: Balconies, which were common areas, adjoining residential units and office spaces were to be for the exclusive, free use of the respective unit owners. (However, maintenance costs as per Article 12 were still borne by the user).

- Article 9, Paragraph 2 (main part): Portions of the rooftop tower, exterior walls, and pipe shafts could be used, free of charge, by the owners of office units (Y was such an owner) for the installation of office cooling towers and commercial signage for shops and offices.

- Article 12, Paragraph 1: The costs for repair, maintenance, and management of the common areas used exclusively or specifically by certain unit owners under Article 9 (balconies, designated rooftop/wall sections for office use) were to be borne by those respective users. The repair, maintenance, and management of all other common areas were to be carried out by the Manager (管理者 - kanrisha, typically the management association or its appointed representative), with costs covered according to other provisions in the rules.

The Lawsuit by Another Unit Owner:

X, another unit owner in Condominium Kou, filed a lawsuit against Y. X claimed that Y had been unjustly enriched by receiving rent from Company A for the use of common areas. X sought payment of an amount equivalent to X's co-ownership share of the ¥122,000 monthly rent attributable to the common areas, plus interest for late payment.

Lower Court Rulings:

- First Instance (Yokohama District Court, January 30, 2012): The District Court dismissed X's claim. It reasoned that the free-use provisions in Article 9, Paragraph 2 of the condominium's bylaws were not in violation of the Condominium Ownership Act and were valid. Furthermore, it found that Y's lease to Company A for the mobile phone base station, considering its purpose and other circumstances, fell within the scope of these authorized free-use provisions.

- High Court (Tokyo High Court, December 13, 2012): The High Court also dismissed X's claim but on different grounds.

- It determined that the installation of the mobile phone base station (antenna masts, cabling, etc.) did not fall under the types of equipment (office cooling towers, commercial signage) permitted for free use by office unit owners under Article 9, Paragraph 2 of the bylaws.

- Therefore, Y's use of the common areas for this purpose and the generation of rental income lacked legal justification. This constituted unjust enrichment at the expense of other unit owners, who were entitled to a share of this enrichment corresponding to their co-ownership stake in the common areas (as per Article 19 of the Condominium Ownership Act).

- However, the High Court concluded that the management of common areas in a condominium is subject to collective regulation (citing Articles 18 and 26 of the Condominium Ownership Act). It held that the exercise of an unjust enrichment claim arising from the misuse of common areas is a matter of managing those common areas. As such, the right to pursue this claim is entrusted to the Manager (i.e., the management association) and cannot be exercised by individual unit owners independently.

X, disagreeing with the High Court's conclusion that an individual owner could not exercise the claim, appealed to the Supreme Court, with the appeal being accepted.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court, in its decision of September 18, 2015, upheld the High Court's dismissal of X's claim. However, it did so based on its own distinct line of reasoning regarding the exercise of unjust enrichment claims by individual unit owners.

The Supreme Court's judgment can be broken down into three main points:

Point I: The Unjust Enrichment Claim Belongs to Individual Unit Owners, Who Can Generally Exercise It.

The Court first stated that when one unit owner leases common areas to a third party and derives rental income, any unjust enrichment claim arising from this (specifically, for the portion of rent corresponding to each other unit owner's co-ownership share in the common areas) accrues to each individual unit owner.

As a consequence of this, the Court affirmed that, as a general principle, each unit owner is entitled to individually exercise this right and file a claim to recover their share.

Point II: The Framework of Collective Management and the Association's Power to Restrict Individual Claims.

The Court then turned to the Condominium Ownership Act (建物の区分所有等に関する法律 - Tatemono no Kubun Shoyū tō ni Kansuru Hōritsu).

- It noted that the Act (Article 3, first part) stipulates that unit owners collectively form an association (区分所有者の団体 - kubun shoyūsha no dantai) to manage the building, its site, and ancillary facilities.

- The Act (Chapter 1, Section 5) also provides for the association's decision-making processes, including general meetings, resolutions, and the establishment of bylaws (規約 - kiyakku), which are the association's self-governing rules.

- Critically, Article 18, Paragraph 1 (main part) and Paragraph 2 of the Act specify that matters concerning the management of common areas are to be decided by resolutions at general meetings of the association or stipulated in the bylaws. This subjects the management of common areas to collective regulation, reflecting the special nature of co-ownership in a condominium, where common areas serve the collective purpose of all unit owners.

- The act of leasing common areas to a third party is undeniably a matter of common area management. The unjust enrichment claim, in this context, serves to restore to the unit owners the benefits they lost due to being unable to capitalize on such third-party leasing of the common areas. Therefore, the claim is intimately connected to the management of common areas.

- Given this close connection, the Supreme Court reasoned that the unit owners' association has the authority to decide, either through a resolution at a general meeting or by a provision in the bylaws, that only the association itself can exercise such unjust enrichment claims.

- If such a collective decision (resolution or bylaw) exists, then individual unit owners are precluded from independently exercising these claims.

Point III: Implied Restriction Based on Existing Bylaw Provisions for Common Area Management.

This was the pivotal point for the outcome of X's case. The Supreme Court stated that considering the overarching intent of the Condominium Ownership Act to subject common area management to collective regulation, the following interpretation applies:

- If bylaws or a resolution of the unit owners' association grant the Manager (the executive body of the association) the authority to (a) manage the common areas and (b) permit the use of common areas by specific parties, then such bylaws or resolutions are to be understood as implicitly including an agreement that only the unit owners' association (acting through its Manager) may exercise unjust enrichment claims arising from the use of those common areas.

Applying this interpretation to Condominium Kou's situation:

- The existing management rules (bylaws) of Condominium Kou did contain provisions stating that the Manager was responsible for the management of common areas. They also included clauses (Article 9) that permitted certain unit owners (including Y, for limited purposes) to use portions of the common areas, even if free of charge.

- The Supreme Court held that these existing bylaw provisions, which granted the Manager authority over common area management and usage permissions, should be interpreted as encompassing the understanding that only the management association could pursue the type of unjust enrichment claim Y was making.

- Therefore, X, as an individual unit owner, was not entitled to exercise the unjust enrichment claim against Y, even though the claim, in principle, pertained to X's share.

Conclusion of the Supreme Court:

Based on this reasoning, while the High Court's rationale was different, its conclusion to dismiss X's claim was ultimately correct. The Supreme Court therefore dismissed X's appeal.

Analysis and Broader Implications

The Supreme Court's 2015 decision offers important, albeit nuanced, guidance on a common point of friction in condominium governance.

1. Affirmation of Divided Entitlement (The Principle):

The judgment is significant for explicitly stating that the substantive right to an unjust enrichment claim arising from the unauthorized commercial use of common areas belongs to each individual unit owner in proportion to their co-ownership share. This aligns with the general principle of divisible claims in co-ownership under the Civil Code and was consistent with the underlying premises of the 2002 amendments to the Condominium Ownership Act. This clarification is a foundational aspect of the ruling.

2. Divergence from the High Court on the Exercise of the Right:

The Supreme Court's approach marks a notable departure from the High Court's more restrictive stance. The High Court had suggested that such claims were inherently matters of collective management and thus could only be pursued by the management association. The Supreme Court, in contrast, established that individual unit owners do have the right to exercise their claims in principle, but this right can be limited by the collective will of the unit owners expressed through bylaws or resolutions. This creates a default rule of individual standing, with an opt-out mechanism for collective action.

3. The Controversial "Implied Restriction" (The Practice):

The most debated aspect of the Supreme Court's decision lies in Point III – its broad interpretation of existing, general bylaw provisions concerning common area management. The Court found that clauses empowering the Manager to oversee common areas and authorize their use were sufficient to imply a restriction on individual unit owners' rights to sue for unjust enrichment.

Many legal commentators have criticized this as a significant "logical leap." If such general management clauses, common in most condominium bylaws, are deemed to implicitly restrict individual claims, then the "principle" that individual owners can sue (Point I) becomes largely theoretical. In practice, the outcome under the Supreme Court's reasoning may often be similar to the High Court's conclusion: individual claims are barred. This has led to observations that the Supreme Court, while establishing a more individual-rights-oriented starting point, ultimately arrived at a result that heavily favors collective action through a very permissive interpretation of what constitutes a "restriction."

4. The Fate of Recovered Funds:

The judgment focuses on who can exercise the claim, but the commentary surrounding it raises important questions about the ultimate disposition of any funds recovered by the management association. If individual unit owners have already borne certain costs associated with the common areas (e.g., through their share of property taxes), and if, in cases like the installation of mobile phone base stations, the lessee (the phone company) often covers direct maintenance costs for its equipment, what happens to the rental income collected by the association?

Unless the bylaws specify how such recovered funds should be used (e.g., allocated to the repair reserve fund, used to offset common management fees), there's a risk that this income (after any applicable corporate taxes if the association is structured as a taxable entity) might simply accumulate as an unearmarked surplus within the association. This might not directly benefit the individual unit owners in proportion to their "loss" or entitlement.

5. The Call for Explicit Bylaw Provisions:

To effectively and clearly restrict individual claims and ensure transparency regarding the use of recovered funds, legal experts suggest that condominium bylaws should be much more explicit. For instance, bylaws could state: "The Manager, on behalf of the Management Association, shall be exclusively responsible for claiming and receiving any monetary restitution, including unjust enrichment, arising from the unauthorized use of common areas or common facilities. Any funds so recovered shall be [e.g., deposited into the long-term repair reserve fund, used to offset common administrative expenses for the following fiscal year, distributed to unit owners according to their share if so resolved at a general meeting]." Such clarity would align with the Supreme Court's framework while mitigating the ambiguities arising from reliance on "implied" restrictions.

6. Distinguishing Claim Types:

The commentary also touches upon potential distinctions between different types of claims related to common areas. Some argue that for claims involving damage to common property, restricting individual lawsuits in favor of collective action by the association is more easily justified, even without highly explicit bylaw provisions. This is because the primary goal is to secure funds for necessary repairs, which is inherently a collective management function. For claims like the recovery of rental income (unjust enrichment), where the funds don't directly correspond to a physical repair need, the argument for restricting individual claims might rely more heavily on clear bylaw provisions detailing the collective benefit or use of such recovered monies.

7. Scope and Nature of the Judgment:

Many legal commentators view this decision as highly fact-dependent, particularly concerning its interpretation of Condominium Kou's specific bylaws. The extent to which its reasoning on "implied restriction" will apply to other condominiums with differently worded bylaws, or to different types of claims involving common areas, remains a subject of ongoing legal analysis.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's September 2015 judgment navigates the delicate balance between the individual property rights of condominium unit owners and the necessities of collective management. It affirms that the right to claim a share of unjust enrichment from the unauthorized commercial use of common areas fundamentally belongs to individual unit owners. However, it also establishes that this right to sue individually can be curtailed by the collective decision of the unit owners, expressed through bylaws or general meeting resolutions.

The ruling's broad interpretation of general management clauses in bylaws as implicitly constituting such a restriction means that, in many practical scenarios, the management association will be the proper party to pursue these claims. This underscores the critical importance for condominium associations to have clear, comprehensive, and explicit bylaws that address not only the management and use of common areas but also the procedures for handling income derived from them and the enforcement of claims related to their misuse. While aiming for a balance, the decision has prompted considerable discussion about the effective ability of individual owners to protect their proportional interests in the common elements of their shared property.