University Tuition Refunds in Japan: Supreme Court Ruling on Early Withdrawal and No-Refund Clauses under the Consumer Contract Act

Judgment Date: November 27, 2006

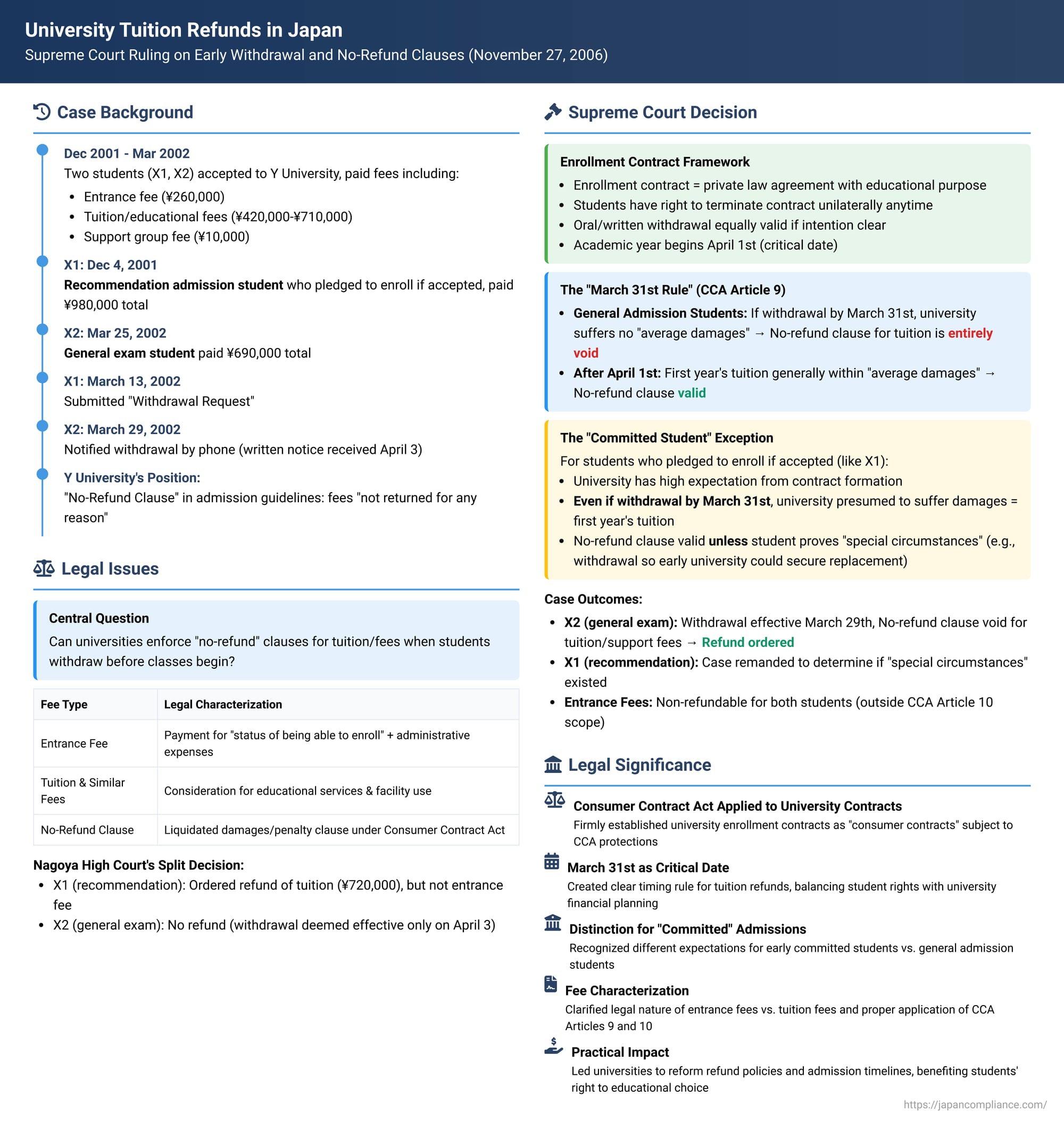

A common and often contentious issue for students and universities in Japan (and elsewhere) is the refundability of pre-paid tuition and other fees when a student decides to withdraw their enrollment before the academic year officially commences. Can universities enforce "no-refund" clauses for all paid amounts, or do students have a right to reclaim at least a portion of these fees? The Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, delivered a landmark judgment on November 27, 2006 (Heisei 17 (Ju) No. 1158 & No. 1159), providing a comprehensive framework for addressing these disputes. The case involved two students, X1 and X2, and Y University, and its interpretation heavily invoked Japan's Consumer Contract Act (CCA).

The Students, the University, and the Withdrawals

The case concerned two students who had been accepted into Y University for the 2002 academic year:

- Plaintiff X1: Was admitted to Y University's Faculty of Arts through a "general recommendation (public application)" admission process. A key condition of this admission was that applicants "must pledge to enroll in this Faculty if accepted." X1 completed the admission procedures and paid the required fees—an entrance fee of ¥260,000, tuition and other educational fees totaling ¥710,000 (for the initial period), and a support group fee of ¥10,000 (totaling ¥980,000)—by the deadline of December 4, 2001. On March 13, 2002, X1 submitted a document titled "Withdrawal Request" (退学願 - taigaku-negai) to Y University, indicating an intention to withdraw.

- Plaintiff X2: Was admitted to Y University's Faculty of Letters and Science through the general entrance examination. X2 also completed the admission procedures and paid the fees: an entrance fee of ¥260,000 by March 1, 2002, and tuition and other educational fees of ¥420,000 plus a support group fee of ¥10,000 by March 25, 2002 (totaling ¥690,000). Around March 29, 2002, X2 informed Y University by telephone of the decision to withdraw. A formal written "Enrollment Declination Notice" (入学辞退届出 - nyūgaku jitai todokede) sent by X2 was received by Y University on April 3, 2002.

Y University's admission guidelines and procedures for both X1 and X2 contained a "No-Refund Clause" (不返還特約 - fuhenkan tokuyaku), stating that once admission documents were submitted and fees were paid, these would "not be returned for any reason whatsoever." University regulations also reflected a similar policy. When X1 and X2 sought refunds, Y University refused, citing the validity of this No-Refund Clause.

The Nagoya High Court (the lower appellate court) had ruled differently for the two students. For X1 (the recommendation admission student who withdrew in mid-March), it ordered Y University to refund the tuition and support group fees (¥720,000), finding the No-Refund Clause void under Article 9, Item 1 of the Consumer Contract Act because the university suffered no demonstrable damage from a withdrawal before the academic year began on April 1st. However, it deemed the entrance fee non-refundable. For X2 (the general admission student), the High Court held that the withdrawal was only effective when the written notice was received on April 3rd. Since this was after the academic year had notionally begun, it dismissed all of X2's refund claims. Both X2 (seeking a refund) and Y University (contesting the refund to X1) appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Comprehensive Framework for University Enrollment Contracts

The Supreme Court used this opportunity to lay out a detailed "General Theory" (総論 - sōron) regarding university enrollment contracts (在学契約 - zaigaku keiyaku), student fees, and the application of the Consumer Contract Act. This was a significant act of judicial interpretation, effectively developing specific legal principles for this unique type of service contract where general Civil Code provisions were deemed insufficient.

I. General Principles Articulated by the Supreme Court:

- (A) Nature of the Enrollment Contract: A university enrollment contract is a private law agreement with characteristics of a bilateral remunerative contract (services for payment). However, it is also deeply influenced by educational laws, public policy concerning education, and educational ideals, making it a sui generis (unique, innominate) contract, not perfectly analogous to standard commercial service agreements.

- (B) Formation of the Enrollment Contract: Generally, an enrollment contract between a student and a university is formed when the student successfully completes all required admission procedures, including the payment of specified fees, within the university's stipulated timeframe. Student status, and the commencement of the university's obligation to provide educational services and the student's obligation to pay (or have paid) for them, typically begins on the official start date of the academic year (usually April 1st in Japan).

- (C) Nature of Student Fees:

- Tuition and Similar Fees (授業料等 - jugyōryō-tō), including items like facility fees, lab fees, and associated support group fees (諸会費等 - shokaishi-tō): These are generally considered to be consideration (payment) for the educational services to be provided by the university and for the use of its facilities and resources.

- Entrance Fee (入学金 - nyūgaku-kin): Unless proven to be unreasonably excessive or to possess other characteristics, the entrance fee is primarily considered consideration for acquiring the "status of being able to enroll" (入学し得る地位 - nyūgaku shiuru chii) at that particular university. It also serves to cover administrative expenses incurred by the university in processing admissions and preparing to accept the student. The Court found that requiring such an entrance fee is not, in itself, contrary to public policy.

- (D) Rescission/Termination of the Enrollment Contract:

- By the Student: Reflecting the constitutional right to education and principles of educational freedom, a student who has entered into an enrollment contract has, in principle, the right to unilaterally terminate (rescind) the contract prospectively at any time. This right is broadly recognized. University regulations that might require formal procedures, such as obtaining permission or submitting specific written forms for withdrawal, generally cannot restrict this fundamental right of termination or negate the legal effect of a student's clear intention to withdraw.

- By the University: Conversely, a university cannot unilaterally terminate an enrollment contract without a justifiable reason.

- Form of Student's Withdrawal: A student's declaration of intent to withdraw is generally effective even if made orally, provided the student's definite intention is clearly expressed. While written notice is preferable for clarity and record-keeping, it is not typically a pre-condition for the validity of the withdrawal itself, even if university rules suggest or require it. (The Court added that an unexcused absence from an entrance ceremony might be interpreted as an implied declaration of withdrawal if university rules explicitly state so).

- Effect of Termination on Fees (in the absence of a valid special agreement):

- If the enrollment contract is terminated before the student officially enrolls (typically April 1st), the student has not yet acquired student status at that university nor received any educational services. In such cases, the university generally lacks the legal basis to retain pre-paid tuition and similar fees (excluding the entrance fee) and is obligated to refund them.

- If termination occurs after April 1st, during an academic term or year for which tuition has been pre-paid, the university is not automatically entitled to retain tuition corresponding to the portion of services not yet provided.

- Entrance Fee Exception: Because the entrance fee is considered payment for acquiring the "status of being able to enroll"—a status obtained upon completing the initial admission procedures and paying the fee—the university is not obligated to refund the entrance fee even if the enrollment contract is subsequently terminated or lapses.

- (E) Nature of No-Refund Clauses (for Tuition, etc.): Clauses in university regulations or admission guidelines stating that pre-paid tuition and similar fees will not be refunded upon withdrawal are to be legally characterized as liquidated damages or penalty clauses related to the termination of the enrollment contract.

- (F) Application of the Consumer Contract Act (CCA): The Supreme Court unequivocally stated that enrollment contracts between students (defined as "consumers" under CCA Art. 2(1)) and universities (which qualify as "business operators" under CCA Art. 2(2), irrespective of their non-profit or public status) are indeed "consumer contracts" as defined in CCA Art. 2(3). Consequently, No-Refund Clauses pertaining to tuition and similar fees in such contracts fall under the purview of the CCA's provisions on liquidated damages clauses.

- (G) Public Policy and No-Refund Clauses (General Validity): The Court acknowledged that No-Refund Clauses serve legitimate university purposes, such as mitigating potential financial losses from student withdrawals (lost tuition revenue, difficulty in reducing fixed costs or recruiting replacements mid-year) and ensuring a stable and qualified student body. Such clauses have a long history in Japanese private universities. Therefore, a No-Refund Clause is not, in itself, contrary to public policy unless it is "grossly unreasonable"—meaning it excessively restricts a student's freedom of choice in selecting a university or otherwise results in the university gaining an excessive profit at the student's significant and unfair disadvantage.

- (H) Validity of No-Refund Clauses under CCA Article 9, Item 1:

- This CCA provision states that clauses stipulating liquidated damages or penalties are void "to the extent that they exceed the amount of average damages that would normally be incurred by the business operator" as a result of the termination of that type of consumer contract.

- The burden of proof to demonstrate that a No-Refund Clause (or a portion of it) is void because it exceeds these "average damages" generally lies with the student who asserts its invalidity.

- The "March 31st Rule" for Calculating "Average Damages" in University Withdrawals:

- The Court recognized that universities typically anticipate a certain number of withdrawals and make enrollment plans accordingly (e.g., by having multiple admission rounds, creating waiting lists, or admitting more students than the exact capacity).

- If a student's withdrawal (termination of the enrollment contract) occurs by March 31st (i.e., before the academic year begins on April 1st), it is generally considered to be within the scope of withdrawals that the university has already "factored in." In such cases, the Court ruled that, in principle, no "average damages" are deemed to be incurred by the university due to that individual withdrawal. (Administrative costs associated with the initial admission process are considered covered by the non-refundable entrance fee). Therefore, a No-Refund Clause pertaining to tuition and similar fees is entirely void under CCA Art. 9(1) for withdrawals by March 31st.

- Conversely, if the withdrawal occurs on or after April 1st, the student has acquired student status, and the university has commenced its obligations. In such cases, the first academic year's pre-paid tuition and similar fees are, in principle, considered not to exceed the average damages the university would incur (given that university budgets are typically annual, educational resources are committed, and replacing a student mid-year is difficult). Thus, for withdrawals on or after April 1st, the No-Refund Clause for that initial year's tuition and fees is generally valid.

- The "Exclusive Enrollment" (専願 - sengan) / Committed Student Exception: A critical distinction applies to students admitted through processes that require a binding commitment to enroll if accepted (e.g., certain recommendation-based admissions where the student effectively forgoes other immediate options, like X1). For such students:

- The university's expectation of their enrollment is very high from the moment the enrollment contract is concluded.

- If such a "committed" student withdraws, even before March 31st, the university is presumed to incur average damages equivalent to the first academic year's tuition and similar fees.

- Consequently, the No-Refund Clause for these fees is generally valid for these students, unless the student can prove the existence of "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō)—for example, that the withdrawal occurred so early in the admissions cycle that the university could, in fact, easily secure a replacement student through other admission channels without incurring loss.

- (I) Inapplicability of CCA Article 10 to Entrance Fees and Non-Voided Portions of No-Refund Clauses:

- The Court found that No-Refund Clauses for tuition, to the extent they are not voided by CCA Art. 9(1) (i.e., they do not exceed average damages), do not "unilaterally harm the interests of the consumer in violation of the fundamental principle of good faith" as proscribed by CCA Article 10.

- Furthermore, the requirement to pay an entrance fee, being consideration for acquiring the "status of being able to enroll," does not "restrict the rights of the consumer or aggravate the obligations of the consumer as compared with the application of non-mandatory provisions of the Civil Code, Commercial Code or other laws." Therefore, the payment of an entrance fee itself does not fall under the scope of CCA Article 10.

II. Application of the General Principles to X1 and X2:

- Enrollment Contract Formation: The Court affirmed that both X1 and X2 had validly formed enrollment contracts with Y University upon completing their respective admission procedures and fee payments.

- Nature of Fees Paid: The entrance fees paid by both were for securing enrollment eligibility. The tuition and support group fees were for educational services and associated costs. The Court found no reason to deem the entrance fee requirement itself void against public policy, nor did CCA Art. 10 apply to it. Thus, X2's claim for a refund of his entrance fee was unfounded from the outset.

- Effectiveness of X2's Withdrawal (General Admission Student):

- The Supreme Court found that X2's telephoned notice of withdrawal to Y University around March 29, 2002, constituted a valid and effective expression of his definite intention to terminate the enrollment contract. This was further evidenced by the written notice received by the university on April 3rd. The High Court had erred in deeming only the written notice effective.

- Since X2's withdrawal was effective around March 29th (i.e., before the March 31st cut-off), Y University was deemed to have suffered no average damages.

- Therefore, the No-Refund Clause in X2's contract pertaining to his pre-paid tuition and support group fee was entirely void under CCA Article 9, Item 1. Y University was obligated to refund these amounts to X2. The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's denial of X2's refund for these fees.

- Effectiveness of X1's Withdrawal (Recommendation/Committed Admission Student):

- X1 withdrew on March 13, 2002. As a student admitted under a recommendation scheme requiring a pledge to enroll, Y University's expectation of his enrollment was exceptionally high from the time the contract was formed.

- Consequently, upon X1's withdrawal, Y University was presumed to have incurred average damages equivalent to the first academic year's tuition and support group fee. The No-Refund Clause for these amounts was therefore presumptively valid for X1.

- This presumption could only be rebutted if X1 could prove the existence of "special circumstances"—specifically, that his withdrawal occurred at a time when Y University could still "normally and easily secure a replacement student through other entrance examinations, etc."

- The High Court had ordered a refund to X1 without adequately examining whether such "special circumstances" existed that would negate Y University's presumed damages in the case of a committed student.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court remanded X1's case (specifically, the part concerning the refund of tuition and support group fees) back to the High Court for a factual determination of whether these "special circumstances" were present. If X1 could not prove such circumstances, he would not be entitled to a refund of his tuition and support group fees.

Key Implications of the Supreme Court's Ruling

This comprehensive judgment by the Supreme Court provided much-needed clarity and established a detailed legal framework for disputes over university fee refunds upon early withdrawal:

- Strong Affirmation of Student's Right to Withdraw: The decision firmly establishes a student's general right to terminate their enrollment contract at will, even orally, before the academic year begins.

- Entrance Fees Generally Non-Refundable: The Court characterized entrance fees as payment for securing "enrollment eligibility status" and related administrative costs, making them generally non-refundable once paid, provided they are not excessively high. These fees were also found to be outside the scope of challenge under CCA Article 10.

- Tuition and Similar Fees – The March 31st Rule: For pre-paid tuition and other educational fees, the Court, applying CCA Article 9(1), created a crucial distinction based on the timing of withdrawal:

- Withdrawal by March 31st (for general admission students): Universities are presumed to suffer no average financial loss. Thus, any "no-refund" clause for tuition is entirely void, and these fees must be refunded.

- Withdrawal on or after April 1st: The first year's tuition is generally considered to fall within the university's "average damages." Thus, a "no-refund" clause for this amount is typically valid.

- Special Rule for "Committed" Admissions: Students admitted under schemes requiring a binding pledge to enroll (e.g., certain recommendation tracks) face a different presumption. If they withdraw, even before March 31st, the university is presumed to suffer damages equivalent to the first year's tuition, and the "no-refund" clause is likely valid, unless the student can prove special circumstances showing the university could easily find a replacement.

- Consumer Contract Act as a Key Regulatory Tool: The ruling decisively brought university enrollment contracts under the ambit of the Consumer Contract Act, particularly utilizing Article 9(1) to scrutinize the fairness of no-refund clauses as liquidated damages provisions.

- Judicial "Law Creation": The judgment is a significant example of the judiciary developing specific legal principles for a unique type of contract (the enrollment contract) where general provisions of the Civil Code were not sufficiently detailed.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's November 2006 rulings in the Y University cases have had a lasting impact on the relationship between students and educational institutions in Japan. By establishing clear (albeit presumptive) rules regarding the refundability of pre-paid fees upon early withdrawal, and by firmly applying the principles of the Consumer Contract Act to enrollment contracts, the Court struck a balance between protecting students' freedom of choice and recognizing the legitimate financial interests of universities. The "March 31st rule" for general admission students, and the distinct considerations for "committed" students, provide a foundational framework for resolving such disputes, emphasizing transparency and fairness in the often significant financial commitments associated with higher education.