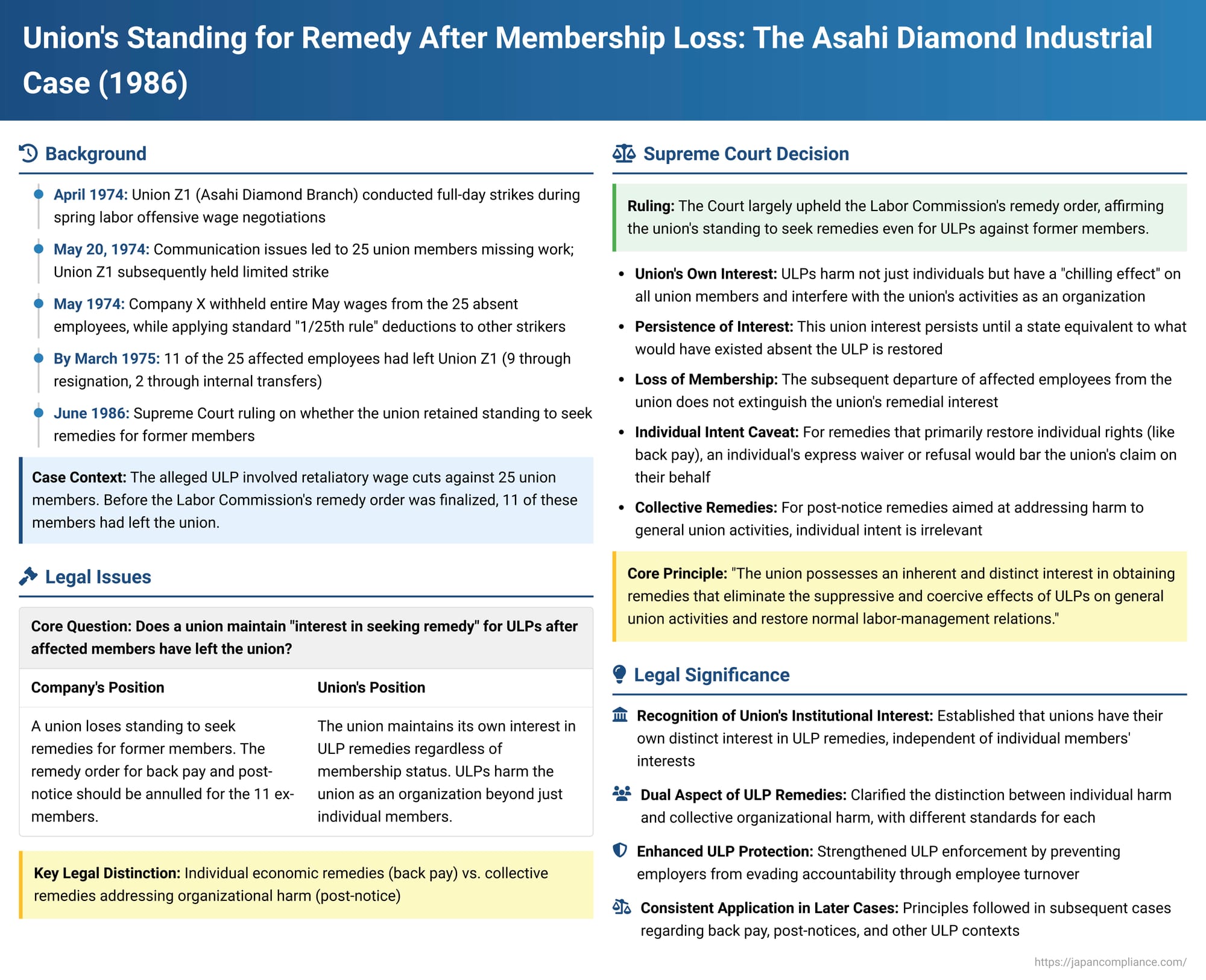

Union's Standing for Remedy After Membership Loss: The Asahi Diamond Industrial Case (Supreme Court of Japan, June 10, 1986)

On June 10, 1986, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a crucial judgment in the Asahi Diamond Industrial Co. case. This decision provided significant clarification on a labor union's "interest in seeking remedy" (救済利益 - kyūsai rieki) for unfair labor practices (ULPs) even when the directly affected employees have subsequently lost their union membership. The ruling emphasized the union's own distinct interest in redressing ULPs due to their broader impact on the union as an organization and its activities.

Case Reference: 1983 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 79 (Petition for Rescission of Unfair Labor Practice Remedy Order)

Appellant (Original Defendant): Commission Y (Kanagawa Prefectural Labor Commission)

Appellee (Original Plaintiff): Company X (Asahi Diamond Industrial Co., Ltd.)

Intervening Unions: Union Z1 (Asahi Diamond Branch of the All Japan Metal and Engineering Workers Union, Kanagawa Regional Headquarters) and Union Z3 (its parent body, the Kanagawa Regional Headquarters).

Judgment of the Supreme Court: The Supreme Court overturned the judgments of the High Court and the District Court in part. It held that the Labor Commission's remedy order, including back pay for former union members and a post-notice requirement, was largely valid, thereby affirming the union's standing to seek such remedies under the circumstances.

Factual Background: Strike, Wage Cuts, and Loss of Union Membership

The dispute stemmed from events during the 1974 spring labor offensive (shuntō):

- The Parties: Company X manufactured and sold diamond tools, with factories in Kanagawa (Tamagawa factory) and Mie. Union Z1 represented employees at the Tamagawa factory (around 206 members at the time), and Union Z2 represented employees at the Mie factory (around 280 members). Union Z3 was their parent union organization.

- Labor Dispute and Strike: During the 1974 wage negotiations, Union Z1, after establishing the right to strike, demanded a ¥39,000 increase in basic salary. Negotiations stalled due to delays by Company X and unsatisfactory offers. From April 15, 1974, Union Z1 conducted a full-scale, all-day strike.

- Events of May 20, 1974: On May 14, Company X offered a total increase of ¥30,000 (including basic salary and family allowance). While Union Z1 found this unsatisfactory, it decided to shift tactics due to the prolonged dispute, opting for limited-duration strikes instead of all-day strikes. On the evening of May 17, Union Z1 held a general meeting and instructed members to gather before work in front of the factory on May 20, with the strike status for that day undecided. However, some members who missed the meeting could not be contacted. As a result, several union members, including Employees A et al., did not report to work on May 20 due to communication issues or personal reasons.

- Decision Not to Strike and Subsequent Limited Strike: On May 20, Union Z1 decided not to conduct an all-day strike. Members who had gathered were informed and began working. However, when administrative-level talks later that day failed to progress, Union Z1 conducted a two-hour limited strike. Ultimately, the 1974 spring dispute involving Company X and Union Z1 ended when both parties accepted a mediation proposal from Commission Y. Union Z1 had conducted strikes totaling 18 days and 2 hours during this period.

- Wage Deductions (The "1/25th Rule" vs. Full Withholding): Company X had a pre-existing agreement (from 1970) with Union Z1 and Union Z2 stipulating that for absences, lateness, or early departure, 1/25th of the monthly salary would be deducted per day. This "1/25th rule" was also applied during strikes. For union members who worked on May 20 except for the two-hour strike, Company X applied this rule and paid their wages accordingly (deducting for 6 days and 5.5 hours, presumably reflecting the total strike duration in May). However, for Employees A et al. (a group of 25 members) who did not work at all on May 20, Company X withheld their entire May wages.

- Loss of Union Membership: By the end of March 1975, before Commission Y issued its remedy order, 11 of the 25 employees in group A et al. had lost their membership in Union Z1 (9 due to resignation from Company X, and 2 due to internal transfers that made them ineligible for Z1 membership).

The ULP Claim, Labor Commission, and Lower Court Rulings

Union Z1, Union Z2, and their parent Union Z3 filed an unfair labor practice claim with Commission Y.

- Commission Y (Kanagawa Prefectural Labor Commission): Found that Company X's withholding of the entire May wages from the 25 employees (Employees A et al.) constituted an ULP under TUA Article 7(1) (disadvantageous treatment due to union membership/activity) and 7(3) (domination or interference with union administration). It ordered Company X to pay these 25 employees the wage difference based on the normally applied "1/25th rule" and to post a notice (a "post-notice" of apology and assurance of non-repetition).

- Yokohama District Court: Company X sought to annul this order. The District Court agreed that the wage withholding was a ULP. However, it annulled the part of the order requiring back pay to the 11 employees who had subsequently lost their Union Z1 membership. The court reasoned that if a member voluntarily leaves the union, the union itself generally loses its interest in seeking remedies for that individual's past disadvantages, absent special circumstances.

- Tokyo High Court: Both Company X and Commission Y appealed. The High Court largely upheld the District Court's decision, with some modifications, and also annulled the post-notice requirement.

Commission Y, supported by the unions, then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Affirming Union's Remedial Interest

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court and District Court judgments in crucial aspects, largely reinstating the Labor Commission's original order. The Court's reasoning focused on the nature of the ULP and the union's inherent interest in seeking remedies:

I. Nature of the Unfair Labor Practice (Wage Cut)

The Supreme Court first affirmed that the full wage cut for the 25 employees was indeed a ULP.

- It characterized the action as retaliation for Union Z1's strike activities during the spring labor offensive.

- This ULP was not merely an infringement of the 25 employees' individual employment rights and financial interests. More broadly, through the harm inflicted on these individuals, the company's action inevitably had a chilling effect on the willingness of all Union Z1 members to engage in union activities, suppressed general union activity, and constituted domination or interference with the administration of Union Z1. This is why it fell under TUA Article 7(1) and 7(3).

II. The Union's "Own Interest" in Seeking Remedy

Based on this characterization of the ULP, the Court found:

- Union Z1 and its parent Union Z3 possessed an inherent and distinct interest in obtaining the remedies ordered by the Labor Commission (including payment of the wage differential to the 25 individuals and the post-notice). This interest stemmed from the need to eliminate the suppressive and coercive effects of the ULP on general union activities and to restore a normal collective labor-management relationship.

- This "union's own interest" in seeking the remedy is separate from the individual employees' personal interest in recovering their lost wages.

III. Effect of Subsequent Loss of Union Membership on the Union's Remedial Interest

Critically, the Court held:

- The union's interest in obtaining the remedy (including back pay for the affected individuals) persists until a factual state equivalent to what would have existed absent the ULP is restored.

- The subsequent loss of union membership by 11 of the affected employees (after the ULP occurred but before the remedy order was finalized) does not extinguish or diminish the union's own remedial interest.

- The reasoning is that the chilling effect of the ULP on general union activities does not simply disappear because the specific individuals who were targeted are no longer members.

IV. The Individual Employee's Intent as a Potential Limitation (for Personal Remedies)

While affirming the union's own interest, the Court introduced a caveat concerning remedies that primarily restore an individual's rights and benefits:

- When a ULP remedy sought by a union takes the form of restoring an individual member's (or former member's) employment-related rights and interests (such as back pay), it is reasonable to conclude that such a remedy cannot be realized by completely disregarding the will of the individual concerned.

- Therefore, if an affected individual actively expresses an intention to waive their right to such recovery, or clearly states that they do not wish for the union to pursue the recovery of their personal rights/benefits through the ULP claim, then the union cannot seek that specific form of relief for that individual.

- However, absent such an active expression of waiver or refusal by the individual, the union can seek the remedy on their behalf, regardless of whether the individual has subsequently lost union membership.

V. Application to the Facts Regarding Wage Payments to Former Members

In this case:

- The 11 employees who had lost their Union Z1 membership due to resignation from the company or internal transfer had not expressed any intention to waive their claim to the improperly withheld wages.

- They had also not indicated that they did not want Union Z1 or Z3 to pursue the recovery of these wages on their behalf.

- On the contrary, they had reportedly received an advance payment from Union Z1 for the amount of the wage cut and had authorized the union to receive any back pay recovered from Company X.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that Union Z1 and Z3 were entitled to seek the payment of the wage difference for these 11 former members.

VI. The Post-Notice Remedy

Regarding the Labor Commission's order for Company X to deliver a letter of apology/assurance (post-notice) to Union Z1 and post it in the workplace:

- The Court stated that this type of remedy is aimed solely at eliminating or preventing the infringement upon general union activities, rather than restoring the individual employment rights of the 25 affected employees.

- Consequently, Union Z1 and Z3 were entitled to seek the post-notice remedy concerning the ULP wage cut (even as it pertained to the 11 former members) irrespective of those individuals' subsequent loss of union membership or their personal intentions.

The Supreme Court therefore reversed the lower courts' decisions that had annulled parts of the Labor Commission's order concerning the 11 former members and the post-notice.

Analysis and Significance

The Asahi Diamond Industrial case is a pivotal decision that clarified a union's standing to pursue ULP remedies, even for individuals who are no longer members.

- Union's Inherent Remedial Interest: The judgment firmly established that a union has its own, distinct interest in seeking redress for ULPs. This interest is grounded in the fact that ULPs, even if targeting specific individuals, have a broader "chilling effect" on the union as a whole, its activities, and the collective labor relations order. Remedying the ULP is thus crucial for the union's own institutional well-being and its ability to function effectively.

- Distinction Between Union and Individual Interests: While ULPs often involve individual harm, the Court emphasized the collective dimension. For remedies that directly benefit an individual (like back pay), the individual's active refusal to accept the remedy can be a bar. However, for remedies aimed at the collective (like a post-notice), the individual's stance is less critical. This recognizes that ULPs have both individual and collective victims and effects. The PDF commentary links this dual aspect to the reasoning in the Daini Hato Taxi case (Supreme Court, Grand Bench, 1977), which also acknowledged both individual harm and damage to overall union activities in ULP dismissals.

- Impact of Loss of Membership Qualified: The ruling clarifies that the mere loss of union membership by an affected employee does not automatically extinguish the union's right to seek remedies concerning the ULP committed against that employee while they were a member. This prevents a situation where an employer might evade full accountability for a ULP simply due to employee turnover.

- Post-Notice as Primarily a Union-Focused Remedy: The judgment strongly positions remedies like the posting of notices as primarily serving the union's interest in rectifying the broader damage to union activities and workplace order, making individual consent or continued membership less of a factor for such remedies.

- Strengthening ULP Enforcement: By affirming the union's broad standing, the decision strengthens the ULP remedy system, allowing unions to pursue justice and restore normal labor relations even if the directly impacted individuals have moved on, provided those individuals do not actively oppose the union's efforts on their behalf for personal remedies.

- Consistency in Subsequent Rulings: The principles laid down in Asahi Diamond have been influential. The PDF commentary notes that its logic has been followed in later Supreme Court cases concerning issues like back pay and post-notices (e.g., Ryoseikai case, Kominami Memorial Hospital case), and even extended to different types of ULPs, such as refusal to bargain where the subject individuals of the bargaining later resigned (e.g., OK Lease case).

Conclusion

The Asahi Diamond Industrial Supreme Court judgment is a significant contribution to Japanese unfair labor practice law. It robustly affirms a labor union's intrinsic interest in seeking remedies for ULPs that harm its members and its overall operational environment. While an individual's wishes are relevant for remedies directly restoring their personal rights and benefits, the union's ability to pursue redress for the broader impact of ULPs, particularly through measures like post-notices, remains intact even if affected members subsequently leave the union. This decision reinforces the protective goals of the ULP system by ensuring that unions can effectively challenge and remedy employer actions that undermine lawful union activities and disturb sound labor-management relations.