Union's Right to Seek Judicial Confirmation of Bargaining Status: The JNR (Kokuro) Railway Pass Case (Supreme Court of Japan, April 23, 1991)

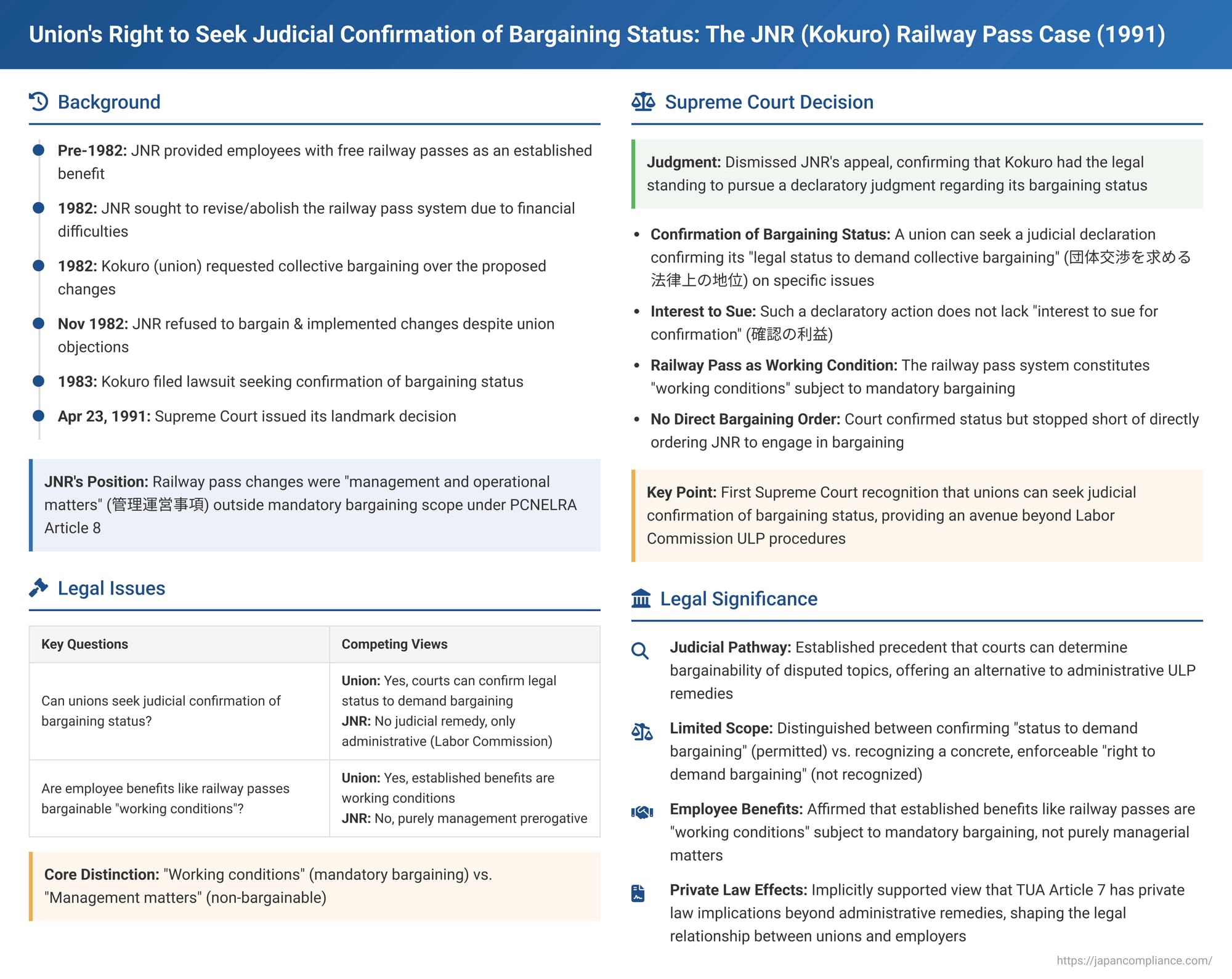

On April 23, 1991, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in a case involving the Japanese National Railways (JNR), later the JNR Settlement Corporation (JNRSC), and the National Railway Workers' Union (Kokuro). This decision was the first by the Supreme Court to affirm a labor union's ability to seek a declaratory judgment from a court confirming its "legal status to demand collective bargaining" on specific disputed matters, even if it stopped short of compelling bargaining through a direct court order. The case also touched upon the crucial distinction between bargainable "working conditions" and non-bargainable "management and operational matters."

Case Reference: 1987 (O) No. 659 (Petition for Confirmation of Duty to Engage in Collective Bargaining)

Appellant (Original Defendant): Company Y (JNR Settlement Corporation, formerly Japanese National Railways - JNR)

Appellee (Original Plaintiff): Union X (National Railway Workers' Union - Kokuro)

Judgment of the Supreme Court: The appeal by Company Y is dismissed. The appellant shall bear the court costs.

Factual Background: The Railway Pass Dispute and Refusal to Bargain

The dispute centered on a long-standing employee benefit at JNR:

- The Railway Pass System: Company Y (JNR) had a system providing its employees with free railway passes (乗車証制度 - jōshashō seido) for use on JNR lines.

- Proposed Changes and Union Opposition: Due to its worsening financial situation, Company Y, as part of its restructuring efforts, initiated a review aimed at revising or abolishing this pass system. Union X (Kokuro) strongly opposed these changes, asserting that the provision of railway passes had become an established part of the employees' working conditions.

- Refusal to Bargain: Union X made several written and oral requests to Company Y for collective bargaining over the proposed changes to the pass system. Company Y refused these requests. Its rationale was that the revision or abolition of the railway pass system constituted a "matter concerning the management and operation of the enterprise" (管理運営事項 - kanri unei jikō). Under the proviso of Article 8 of the then-Public Corporation and National Enterprise Labor Relations Act (PCNELRA), such matters were deemed outside the scope of mandatory collective bargaining.

- Implementation of Changes: Despite Union X's objections and demands for bargaining, Company Y proceeded with measures to revise/abolish the railway pass system on November 13, 1982.

- Lawsuit by Union X: Union X subsequently filed a lawsuit against Company Y. It sought a declaratory judgment confirming Company Y's obligation to engage in collective bargaining over the railway pass issue (along with three other items). Union X also claimed damages for Company Y's refusal to bargain.

Rulings of the Lower Courts

- Tokyo District Court: The District Court confirmed that Union X possessed the "legal status to demand collective bargaining" (団体交渉を求める法律上の地位 - dantai kōshō o motomeru hōritsu-jō no chii) concerning the railway pass system and the other items presented. However, it dismissed Union X's claim for damages.

- Tokyo High Court: Company Y appealed the confirmation, and Union X cross-appealed the dismissal of its damages claim. The High Court dismissed both appeals, upholding the District Court's judgment. The High Court reasoned that:

- Article 7 of the Trade Union Act (TUA), which defines unfair labor practices including refusal to bargain, could not be denied private law effects given its close relationship with Article 28 of the Constitution (guaranteeing workers' fundamental labor rights).

- TUA Article 7 establishes a private law relationship wherein a union has the legal status to request collective bargaining, and the employer has a corresponding legal status to respond.

- The current lawsuit was not seeking to enforce a concrete right to specific bargaining sessions but rather to resolve the dispute over whether the subject matters, including the pass system, were indeed bargainable topics—i.e., whether Union X had the status to demand bargaining on them.

Company Y (by then the JNR Settlement Corporation, following JNR's privatization which occurred after the High Court's final oral arguments but before this Supreme Court judgment) appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Affirming Judicial Confirmation of Bargaining Status

The Supreme Court dismissed Company Y's appeal, thereby upholding the lower courts' decisions.

- Confirmation of "Legal Status to Demand Collective Bargaining" is Lawful:

The Court affirmed that Union X's lawsuit, seeking confirmation of its legal status to demand collective bargaining with Company Y on the specified matters (including the railway pass system), did not lack the "interest to sue for confirmation" (確認の利益 - kakunin no rieki) and was therefore a lawful suit. It found the High Court's judgment on this point to be "just and can be approved."

The Court also noted that JNR's transformation into the JNRSC after the High Court's oral arguments did not extinguish this interest, as Union X's demands could be construed as seeking the continuation of substantively similar working conditions, a matter potentially still bargainable with JNRSC for its remaining or transitioning employees. - Railway Pass System as a "Working Condition":

The Supreme Court explicitly upheld the High Court's determination that the matters raised by Union X, including the railway pass system, constituted "matters concerning working conditions" under the relevant provision of the PCNELRA (Article 8, Item 4 of the pre-amendment Act). As such, they were legitimate subjects for collective bargaining. This rejected Company Y's primary defense that the pass system was purely a matter of managerial prerogative.

The judgment was unanimous.

Analysis and Significance

This JNR (Kokuro) case is a landmark decision in Japanese labor law for its recognition of a judicial pathway for unions facing bargaining refusals, although the scope of that pathway is specific.

- Judicial Confirmation of Bargaining Status:

The most significant aspect of this ruling is that it was the first Supreme Court decision to explicitly affirm that a labor union can seek a declaratory judgment from a court confirming its "legal status to demand collective bargaining" on particular issues. This provided unions with a form of judicial recourse when employers refused to bargain on the grounds that a subject was non-negotiable.

The PDF commentary suggests this decision was influenced by evolving academic theories that, while finding it difficult to affirm a directly enforceable "concrete right to demand bargaining" (具体的団交請求権 - gutaiteki dankō seikyūken) in court, proposed that confirming the status to demand bargaining was a more viable form of judicial relief. - Distinction from a "Concrete Right to Demand Bargaining":

It is crucial to note, as the PDF commentary emphasizes, that the Supreme Court did not recognize a "concrete right to demand collective bargaining" that would allow a court to directly order an employer to come to the bargaining table and negotiate in a specific manner. The judgment was limited to confirming the union's status and the bargainability of the subject matter. The practical effect in compelling a recalcitrant employer to bargain substantively is therefore somewhat limited, though a judicial declaration can exert considerable moral and persuasive pressure. - Private Law Implications of TUA Article 7:

The High Court, whose reasoning was largely upheld, explicitly stated that TUA Article 7 (which defines refusal to bargain as a ULP) has private law implications beyond simply providing the basis for administrative remedies by Labor Commissions. It helps define the legal relationship and respective statuses of employers and unions concerning collective bargaining. The Supreme Court’s affirmation of the lower court judgment implicitly supports this view. The PDF commentary discusses differing academic views on whether TUA Article 7 directly creates private rights or if such rights are derived from a combination of constitutional guarantees (Article 28) and other TUA provisions (like Article 1 or Article 6). - Bargainability of Employee Benefits (Railway Passes):

The Court’s determination that the railway pass system constituted "working conditions" and was thus a mandatory subject of bargaining is also significant. Employers frequently attempt to unilaterally alter or abolish established benefits by classifying them as non-bargainable "management and operational matters." This ruling affirmed that such established benefits, even if not direct wages, are typically considered part of the overall employment conditions subject to negotiation. - Context of Judicial vs. Administrative Remedies:

In Japan, the primary recourse for a union facing a refusal to bargain is to file a ULP complaint with the Labor Commission, which can issue a remedial order (e.g., an order to bargain). The question of whether, and to what extent, courts can provide direct judicial relief has been a long-standing debate.

The PDF commentary notes that historically, lower court decisions were divided, with many in the earlier post-war period affirming a direct right to seek judicial orders compelling bargaining, often through provisional dispositions. Later, particularly from the mid-1970s, a more skeptical view became prevalent in courts, denying a directly enforceable private right to bargain. The "status confirmation" approach adopted in this JNR case can be seen as a nuanced middle path, allowing some judicial involvement without directly ordering the act of bargaining itself. - Limited Practical Efficacy and Ongoing Debates:

While providing a form of judicial affirmation, the "status confirmation" remedy has limitations in terms of compelling an unwilling employer to bargain effectively. The PDF commentary alludes to ongoing discussions and alternative theories, such as a "bifurcated bargaining right" (distinguishing between an abstract right to bargain and a concrete right that might be enforceable in specific circumstances), aimed at addressing the practical efficacy of judicial remedies.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1991 judgment in the JNR (Kokuro) railway pass case marked an important development in the legal framework surrounding collective bargaining in Japan. By affirming a union's right to seek judicial confirmation of its "legal status to demand collective bargaining" on specific issues, it opened a limited but significant avenue for court involvement in disputes over the scope of bargaining. The decision also reinforced the principle that established employee benefits, like the railway pass system, are generally considered "working conditions" subject to negotiation. While not providing a direct means to compel bargaining through court orders, the ruling offered unions a way to obtain judicial clarification on bargainability, thereby potentially strengthening their position in labor-management relations. The case remains a key reference point in the ongoing discourse on the interplay between administrative and judicial remedies for refusals to bargain and the nature of the right to collective bargaining itself.