Union Shop Agreements in Japan: The Freedom to Choose a Union

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of December 14, 1989 (Case No. 1985 (O) No. 386: Claim for Confirmation of Invalidity of Dismissal, etc.)

Appellant: Y Company

Appellees: X (and another)

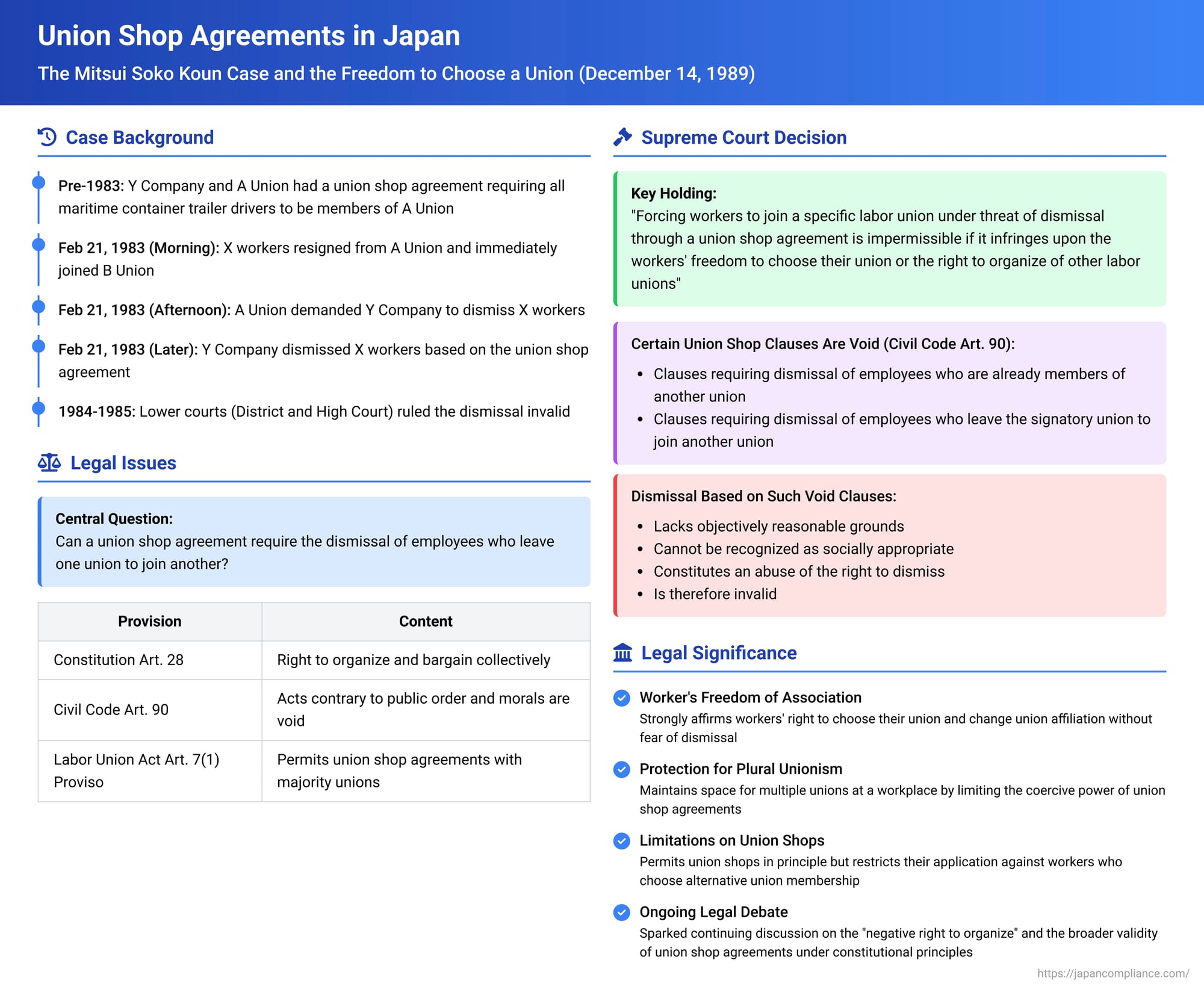

Union shop agreements, which require employees to be members of a specific labor union as a condition of employment, have long been a feature of industrial relations in many countries, including Japan. These agreements aim to strengthen union bargaining power and ensure solidarity. However, they also raise fundamental questions about individual workers' freedom of association. The Japanese Supreme Court's judgment on December 14, 1989, in what is often referred to as the Mitsui Soko Koun case, is a landmark decision that significantly clarified the permissible scope and limitations of union shop agreements, particularly when an employee chooses to switch their union affiliation.

The Factual Matrix: A Clash of Loyalties

The case involved Y Company, an employer, and A Union. These two parties had concluded a union shop agreement which stipulated that all maritime container trailer drivers employed by Y Company must be members of A Union, with exceptions only possible through mutual agreement between Y Company and A Union. The agreement further obligated Y Company to dismiss any such driver who did not join A Union or who was expelled from A Union.

The appellees, X (two drivers), were maritime container trailer drivers employed by Y Company and were initially members of A Union. On February 21, 1983, X took a decisive step: they submitted their letters of resignation to A Union. Immediately upon resigning from A Union, on the very same day, they joined B Union, an entirely different labor union. They promptly notified Y Company of their resignation from A Union and their new affiliation with B Union later that morning.

Events moved swiftly. On that same day, A Union demanded that Y Company dismiss X, invoking the terms of the union shop agreement. Y Company complied and, later that afternoon, dismissed X, citing the union shop agreement as the basis for the termination (referred to as "the Dismissal").

X challenged their dismissal, contending it was invalid and seeking confirmation of their continued status as employees of Y Company.

Lower Courts' Findings

The case proceeded through the lower courts. The Osaka District Court, in its judgment on March 12, 1984, largely ruled in favor of X, finding the dismissal invalid. This decision was subsequently upheld by the Osaka High Court on December 24, 1984. Dissatisfied with these outcomes, Y Company appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Pronouncements: Balancing Rights and Defining Limits

The Supreme Court dismissed Y Company's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions that the dismissals were invalid. In doing so, the Court laid down crucial principles regarding the validity and application of union shop agreements.

1. The Nature and Purpose of Union Shop Agreements:

The Court began by acknowledging the intended function of union shop agreements. It stated that such agreements "aim to indirectly strengthen and expand a labor union's organization by obligating the employer to terminate the employment of workers who fail to acquire or lose membership in that union". This recognition is consistent with previous Supreme Court jurisprudence, such as in the J S M case (1975), which acknowledged the role of union shops in maintaining and strengthening labor unions.

2. The Primacy of Worker's Freedom of Association:

However, the Court immediately juxtaposed this organizational aim with the fundamental rights of workers. It emphasized that "workers have the freedom to choose a labor union in order to exercise their right to organize". This freedom is a cornerstone of the right to organize, which is constitutionally guaranteed in Japan under Article 28 of the Constitution.

3. Equal Respect for All Unions' Right to Organize:

Furthermore, the Court stressed that "the right to organize of other labor unions (those not party to the union shop agreement) deserves the same respect as that of the union that signed the agreement". This principle underscores that no single union's organizational rights can automatically trump those of other legitimate labor organizations.

4. Limitations on Coercion via Union Shop Agreements:

Based on these fundamental rights, the Court set a clear limit: "Forcing workers to join a specific labor union under threat of dismissal through a union shop agreement is impermissible if it infringes upon the workers' freedom to choose their union or the right to organize of other labor unions".

5. Invalidity of Certain Union Shop Clauses (Civil Code Article 90):

This led to the core of the judgment. The Supreme Court declared that specific portions of union shop agreements are void under Article 90 of the Civil Code, which nullifies legal acts contrary to public order and morals. The void portions are those that obligate an employer to dismiss:

* Employees who are already members of a labor union other than the one that signed the union shop agreement (the "signatory union").

* Employees who have resigned from or been expelled by the signatory union but have subsequently joined another existing labor union or formed a new one.

The Court reasoned that enforcing such clauses would directly violate the worker's freedom to choose their union and the organizational rights of other unions, making such enforcement contrary to public policy as informed by the constitutional protection of the right to organize.

6. Dismissal Based on a Void Clause is an Abuse of Right:

Consequently, if an employer dismisses an employee based on such a voided portion of a union shop agreement – that is, in a situation where no legally enforceable obligation to dismiss actually arises – that dismissal "lacks objectively reasonable grounds and cannot be recognized as socially appropriate". The Court, referencing its earlier decision in the J S M case, concluded that unless there are other special circumstances that independently justify the dismissal, such a dismissal "constitutes an abuse of the right to dismiss and is therefore invalid".

Application to X's Case

Applying these principles to the facts before it, the Supreme Court found:

- X had resigned from A Union (the signatory union) and immediately joined B Union (another union).

- In light of the Court's reasoning, Y Company had no legally binding obligation under the union shop agreement to dismiss X because X had joined another union. The clause purporting to create such an obligation was void.

- The Dismissal of X was therefore carried out at a time when Y Company was not under any valid obligation to do so under the union shop agreement.

- The Court found no other special circumstances that would independently provide a rational justification for the Dismissal.

- Therefore, the Dismissal of X lacked objectively reasonable grounds, was not socially appropriate, and constituted an abuse of Y Company's right to dismiss, rendering the Dismissal invalid.

Significance and Implications of the Judgment

The Mitsui Soko Koun decision has had a profound and lasting impact on labor law and industrial relations in Japan:

- Strong Affirmation of Worker's Freedom of Union Choice: The judgment robustly protects a worker's freedom to choose their union affiliation. It clarifies that a union shop agreement cannot be used to "lock in" employees to the signatory union if they wish to join another legitimate labor union. This is a significant safeguard for individual worker autonomy.

- Protection for Plural Unionism and Minority Unions: By invalidating clauses that mandate dismissal for joining another union, the decision offers vital protection for the existence and activities of unions other than the one holding the union shop agreement. It helps to maintain a space for plural unionism within a workplace.

- Clarification on the "Abuse of Right to Dismiss" Doctrine: The case clearly links the invalidity of a dismissal under an unenforceable union shop clause to the broader Japanese labor law doctrine of abusive dismissal. If the contractual basis for the dismissal (the union shop obligation) is void, the dismissal itself lacks objective reasonableness unless other valid grounds exist.

- The "Another Union" Qualification: It is crucial to note the specific scope of this ruling. The Court’s protection extends to employees who leave the signatory union and join another union or form a new one. The judgment does not explicitly address the situation of an employee who resigns from the signatory union and chooses to remain non-unionized altogether. The legal status of union shop clauses in relation to employees who opt for non-membership (as opposed to alternative membership) involves different and more complex debates about the "negative right to organize" (freedom not to join a union), which has a more contested status in Japanese constitutional interpretation.

- Impact on Union Shop Agreement Practices: This ruling has undoubtedly influenced how union shop agreements are understood, drafted, and applied in Japan. While union shops themselves remain permissible for majority unions (under certain conditions, see below), their power to compel dismissal is significantly curtailed when an employee exercises their right to join a different union.

- Use of Civil Code Public Policy (Article 90): The Court's reliance on Article 90 of the Civil Code (public order and morals) as the basis for invalidating parts of a collective labor agreement, with the interpretation of public policy being guided by constitutionally protected rights (Article 28 – right to organize), is a noteworthy legal technique. It demonstrates how general civil law principles can be used to uphold fundamental labor rights.

- Consistency with Subsequent Rulings: Later Supreme Court decisions, such as the N K T M case (1989) and the I M case (1992), have followed the precedent set in Mitsui Soko Koun, reinforcing these principles.

The Ongoing Debate Surrounding Union Shops

The Mitsui Soko Koun decision, while pivotal, did not end the broader academic and legal debate in Japan concerning the fundamental validity and scope of union shop agreements.

- The Negative Right to Organize: A growing number of scholars argue that Article 28 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to organize, should also be interpreted to include the "negative right to organize"—the freedom not to join a union or to resign from one without penalty. This argument often draws on the constitutional emphasis on individual dignity (Article 13) and the general principles of freedom of association (Article 21), suggesting that compelling union membership through the threat of dismissal is inherently problematic. Some scholars point to international standards, such as in Germany, where the negative right to organize is constitutionally recognized. If this view were fully adopted, it could lead to a more fundamental questioning of the validity of union shop agreements in their entirety.

- Interpreting Labor Union Act Article 7, Item 1 Proviso: This proviso states that it is not an unfair labor practice for an employer to conclude a collective agreement requiring union membership as a condition of employment if that union represents a majority of workers at the particular factory or workplace. There is ongoing discussion about the precise meaning of this proviso. Some view it as setting out a validity requirement for union shop agreements. Others argue that since Article 7 primarily deals with unfair labor practices, the proviso merely exempts such majority union shops from being challenged as an unfair labor practice, without necessarily affirming their validity against all other legal challenges (e.g., those based directly on constitutional rights or Civil Code Article 90).

Conclusion

The Mitsui Soko Koun Supreme Court judgment stands as a critical bulwark for workers' freedom to choose their union representation in Japan, even within workplaces covered by union shop agreements. By declaring void those parts of such agreements that mandate dismissal for switching to another union, the Court struck a significant balance between the organizational security interests of unions and the fundamental associational rights of individual employees. While debates about the broader legitimacy of union shops continue, this decision firmly limits their coercive power and reinforces the principle that dismissals must always be grounded in objectively reasonable and socially acceptable justifications. It remains a vital precedent in Japanese collective labor law.