Union Dues and Political Causes: The Kokuro Hiroshima Chihon Supreme Court Ruling on Member Obligations

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of November 28, 1975 (Case No. 1973 (O) No. 499: Claim for Union Dues)

Appellant (Union): X Union (a national railway workers' union)

Appellees (Former Members): Y (and others)

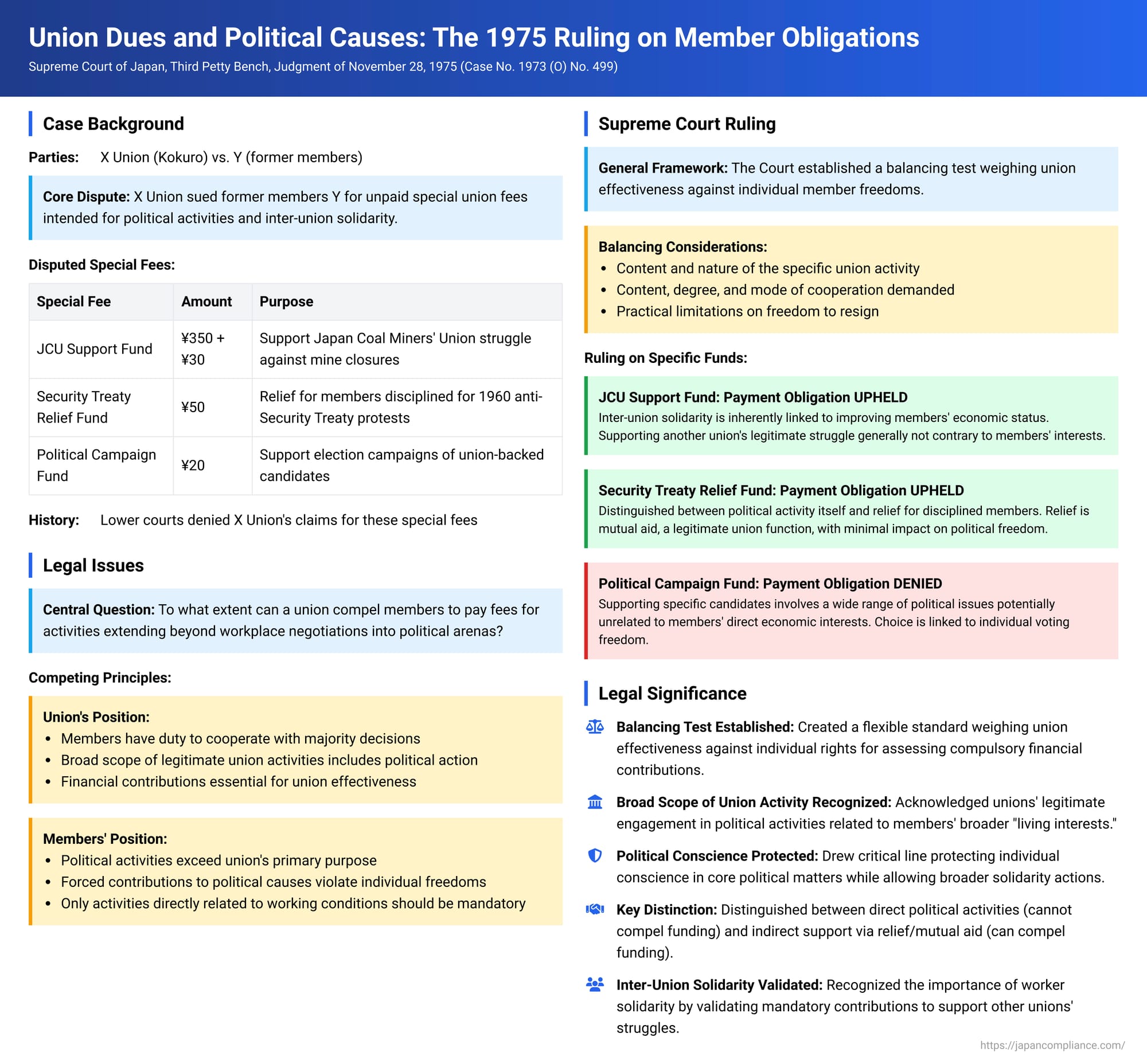

Labor unions, as collective entities, engage in a wide array of activities to advance their members' interests. These activities often require financial contributions from members in the form of regular dues and sometimes special levies for specific purposes. A crucial question arises when these purposes extend beyond direct workplace negotiations into broader social or political arenas: to what extent are individual members, who may not agree with every union endeavor, obligated to fund them? The Japanese Supreme Court's judgment on November 28, 1975, in the Kokuro Hiroshima Chihon case, provides a foundational analysis of this issue, particularly concerning special union fees earmarked for political activities and inter-union solidarity.

The Core Dispute: Unpaid Special Union Fees

The case involved X Union, a prominent national railway workers' union, suing a group of its former members (Y) for unpaid general union dues and, more contentiously, several types of special or temporary union fees (rinji kumiaihi). While the lower courts had addressed various fees, the appeal by X Union to the Supreme Court focused specifically on its claims for the following special fees, which the lower courts had rejected:

- JCU Support Fund (炭労資金 - Tanrō shikin): A fee of ¥350 per member (plus an additional ¥30 from a "Spring Offensive Fund") intended to provide financial support to the Japan Coal Miners' Union (JCU, or Tanrō) during its struggles against coal industry rationalization, particularly concerning the M M Coal Mine, and its campaign for a change in government coal policy.

- Security Treaty Protestors' Relief Fund (安保資金 - Anpo shikin): A fee of ¥50 per member for a fund to provide relief to union members who had faced disciplinary action or criminal charges as a result of their participation in the widespread 1960 protests against the revision of the US-Japan Security Treaty (commonly known as the Anpo struggles). These funds were to be collected and channeled through the General Council of Trade Unions Z, a national labor confederation, and then redistributed.

- Political Campaign Fund (政治意識昂揚資金 - Seiji ishiki kōyō shikin): A fee of ¥20 per member to support the election campaigns of union-backed candidates in the November 1960 general election, by donating these funds to their respective political parties.

The lower courts (Hiroshima District Court and Hiroshima High Court) had denied X Union's claims for these specific fees, generally reasoning that these activities fell outside the union's primary purpose of improving working conditions or that compelling contributions for political causes infringed upon members' individual freedoms. X Union appealed this denial to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's General Framework for Member Obligations

The Supreme Court began by laying out general principles governing the obligations of union members:

- Duty of Cooperation: As long as individuals remain members of a labor union, they have a general duty to participate in activities decided by the union through its proper internal procedures. This includes refraining from actions that would obstruct union activities and, crucially, an obligation to pay union dues which form the economic foundation for these activities.

- Broad Scope of Legitimate Union Activity: The Court recognized that union activities are not static and are not narrowly confined to direct negotiations with employers over wages and working conditions. Historically, while unions emerged to strengthen workers' bargaining power in employment relations, their activities have evolved and expanded. Today, union activities legitimately extend beyond purely economic matters to encompass political, social, and cultural endeavors that are directly or indirectly related to protecting and improving the overall living interests of their members. The Court noted that this expansion has a degree of "social necessity" and, unless specifically restricted by law, such broader activities cannot automatically be deemed outside the union's legitimate scope or as actions a union inherently cannot undertake.

The Balancing Act: Union Objectives vs. Individual Freedoms

Despite acknowledging this broad scope of legitimate union activity, the Supreme Court cautioned that it does not automatically translate into an unlimited power of the union to compel member cooperation, especially financial contributions, for all such activities. This led to the formulation of a key balancing test:

- Premise of Resignation Freedom: The Court noted that members join unions anticipating a certain range of activities and, in principle, are bound by majority decisions, especially since the freedom to resign from the union is generally assured.

- Growing Potential for Conflict: However, as union activities diversify and expand, the potential for conflict between union-mandated activities and an individual member's personal freedoms and rights (as a citizen or human being) increases.

- Practical Constraints on Resignation: The Court also astutely observed that, under contemporary social conditions, union membership itself is often a significant benefit for workers, and the theoretical freedom to resign can be subject to substantial practical constraints.

- The Need for Reasonable Limitation: Given these factors, the Court concluded that merely because a union activity is permissible does not mean that an individual member's obligation to cooperate (particularly financially) can be affirmed unconditionally. Therefore, even in the absence of specific legislative regulations on this point, a "reasonable limitation" must be applied to the scope of the union's authority (its "control power" - tōseiryoku) and, conversely, to the member's duty of cooperation.

- The Balancing Test: This limitation requires a comparative consideration of:

- The content and nature of the specific union activity in question.

- The content, degree, and mode of cooperation demanded from the members.

This balancing must be conducted from the perspective of "harmonizing the effectiveness of union activities based on the majority principle with the fundamental interests of individual members."

Rulings on Specific Funds – Applying the Framework

The Supreme Court then applied this framework to each of the disputed special fees:

1. JCU Support Fund (Inter-Union Solidarity): Payment Obligation Upheld

The Court reversed the lower courts on this point.

- Reasoning: It is common for labor unions to support the struggles of other "fraternal" unions. Such activities are inherently linked to the union's objective of improving its members' economic status, as this goal is often achieved not just through isolated efforts but also through broader solidarity and joint action among workers and unions. Supporting another union's legitimate struggle is generally not contrary to the members' interests.

- The decision to provide such support, unless the support itself is for an illegal activity or similar exceptional circumstance, is a policy matter for the union's autonomous judgment. If such a decision is made by a majority vote, members are generally obligated to cooperate, including through financial contributions.

- The Court found that the lower courts erred in deeming support for the JCU's struggle as outside X Union's objectives, especially considering that the JCU's fight against coal mine closures and for policy changes could indirectly benefit X Union's own members who were facing similar issues (e.g., at the S Mine, a National Railway-operated coal mine).

2. Security Treaty Protestors' Relief Fund (Anpo Fund): Payment Obligation Upheld

The Court also reversed the lower courts on this fund, drawing a crucial distinction.

- The Nature of Political Activity: The Court acknowledged that compelling members to financially support overtly political activities could infringe upon their individual political freedoms, especially the freedom not to be forced into adopting or supporting specific political stances against their will. Activities like the anti-Security Treaty protests, which directly concern national security and foreign policy, are matters for individual citizens to decide based on their personal and autonomous beliefs. Therefore, a union cannot use majority rule to bind all members to cooperate with, or provide direct funding specifically earmarked for, such political struggles themselves. Forcing contributions for such specific political aims would be tantamount to compelling active cooperation and endorsement of that political stance.

- Relief as Mutual Aid: However, the Court distinguished providing relief to members who suffered disciplinary action for participating in such political activities. This relief, the Court reasoned, is primarily an act of mutual aid or assistance (kyōsai katsudō), a well-established and legitimate function of labor unions aimed at maintaining organizational strength and providing economic support to members facing hardship. The focus of such relief is on alleviating the personal detriments suffered by the disciplined members, regardless of the specific nature of the actions that led to the discipline. It is not, the Court argued, a direct endorsement or promotion of the political acts themselves.

- Minimal Impact on Political Freedom: Consequently, compelling members to contribute to such a relief fund was deemed to have a "very slight" impact on their individual political thoughts, views, or judgments. Unlike funds directly supporting the political activity itself, the obligation to contribute to a relief fund for disciplined members was upheld. The fact that the disciplined members' actions might have been illegal did not automatically negate the obligation to contribute to their relief, given the mutual aid purpose.

3. Political Campaign Fund: Payment Obligation Denied

The Court affirmed the lower courts' decisions to deny X Union's claim for this fund.

- Reasoning: Supporting specific political parties or candidates in an election involves a wide range of political issues, many of which may be unrelated to the direct economic interests of union members. The choice of which party or candidate to support is intrinsically linked to the individual's freedom of voting and should be based on personal political beliefs, views, judgments, or sentiments.

- While a labor union, as an organization, is free to decide to support a political party or candidate and to engage in election campaigning (as affirmed in previous cases like the 1968 Mitsui Bibai Coal Miners' Union case), it cannot compel its members to cooperate in such activities, including through mandatory financial contributions. The Court found that coercing financial contributions for this purpose was just as impermissible as coercing active participation in the campaign.

Dissenting Opinions:

It is noteworthy that the judgment included dissenting opinions regarding the JCU Support Fund and the Security Treaty Protestors' Relief Fund. These dissents highlight the inherent difficulty and potential controversy in drawing lines regarding the political nature of union activities and the extent to which members can be compelled to fund them, even indirectly. For instance, one dissent argued that supporting the JCU's struggles was indeed outside X Union's direct objectives and that the majority's reasoning for connecting it was speculative. Another dissent strongly contested the majority's view on the Anpo Fund, arguing that providing relief for those disciplined in the anti-Security Treaty protests was an undeniable extension and endorsement of that political struggle, and thus coercing funds for it infringed on members' political freedom just as direct funding would.

Significance and Implications

The Kokuro Hiroshima Chihon judgment is a landmark decision in Japanese labor law for several reasons:

- Acknowledging the Broad Scope of Union Political Activity: The Court formally recognized that unions can legitimately engage in a wide spectrum of activities, including those with political dimensions, provided they relate to the members' broader "living interests."

- Protecting Individual Conscience in Core Political Matters: It drew a critical line, affirming that unions cannot compel financial contributions for direct partisan electioneering or for direct support of highly ideological political struggles that are matters of individual conscience.

- The "Relief vs. Direct Support" Distinction for Political Actions: The nuanced distinction concerning funds related to members disciplined for political activity (the Anpo Fund) is a key takeaway. Indirect support via relief funds, framed as mutual aid, was deemed permissible where direct funding of the political cause itself would not have been. This distinction, however, was clearly contentious, as evidenced by the dissenting opinions.

- Validation of Inter-Union Solidarity Contributions: The ruling validated the practice of unions levying special fees from their members to provide financial support to other unions engaged in legitimate struggles, recognizing the importance of worker solidarity.

- Introduction of a Flexible "Balancing Test": The overarching framework requiring a balance between union effectiveness and individual member rights provides a flexible standard that allows courts to consider the specific nature of each union activity and the type of cooperation demanded.

- The Role of Freedom to Resign: The Court explicitly linked the general obligation to cooperate with the premise that members are free to resign from the union. However, by also acknowledging the practical limitations on this freedom, it justified the need for the balancing test to protect members from undue coercion even while they remain members.

Conclusion

The Kokuro Hiroshima Chihon decision remains a pivotal judgment in Japanese labor law. It navigates the complex interface between a labor union's collective power and purpose, and the individual member's fundamental rights and freedoms, particularly in the context of financial contributions for activities that extend into the political and social spheres. While affirming a union's right to engage in a broad range of activities and to expect member support, the Supreme Court also established crucial safeguards for individual political conscience and set a precedent for a nuanced, balancing approach to resolving such conflicts. The distinctions it drew, especially regarding political activities, continue to be debated and refined in subsequent jurisprudence.