Union Bill-Posting on Company Property: The Kokutetsu Sapporo Untenku Supreme Court Judgment

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of October 30, 1979 (Case No. 1974 (O) No. 1188: Claim for Confirmation of Status)

Appellant (Employer): Y Company (formerly Japanese National Railways)

Appellees (Employees): X (and three others)

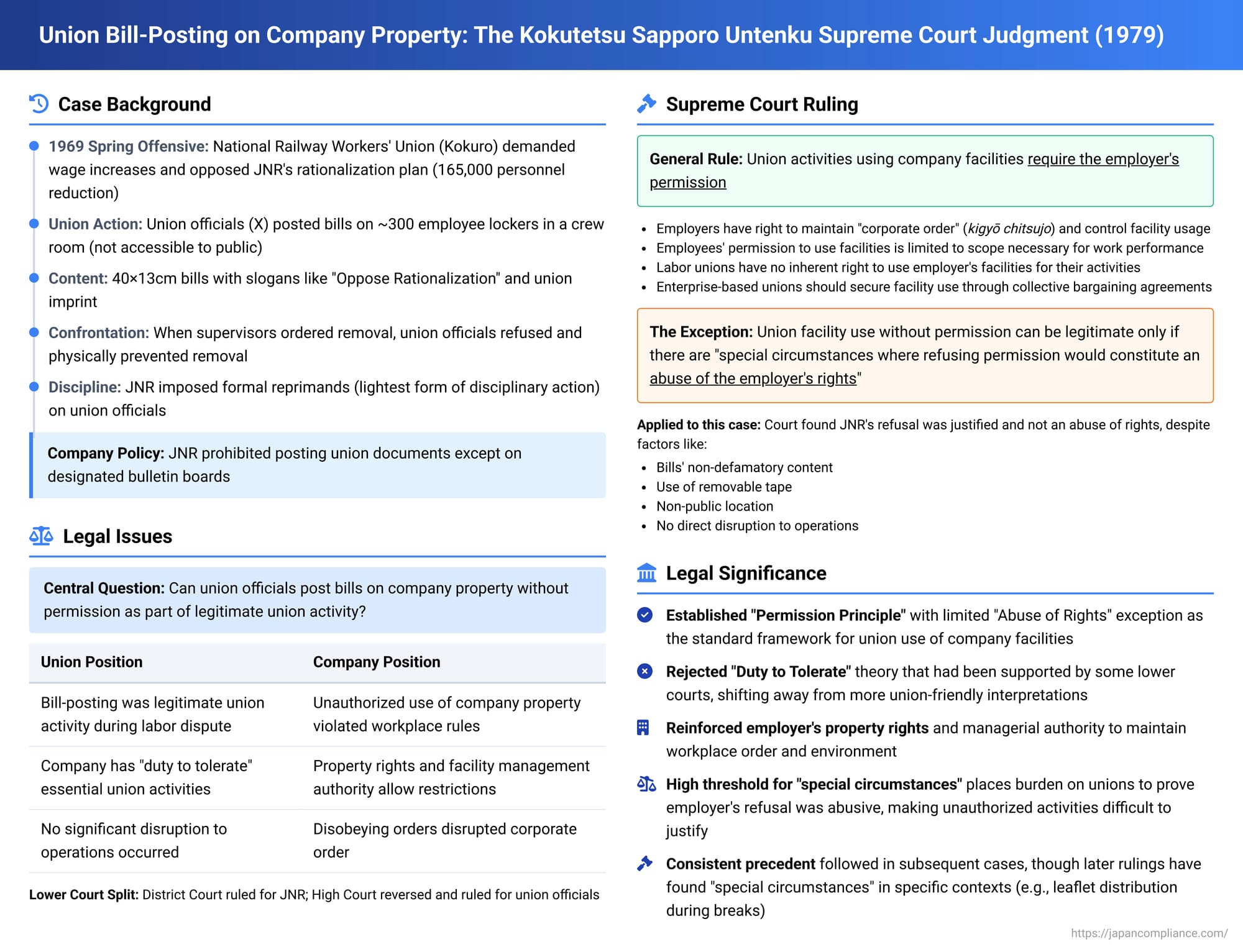

In Japan, where enterprise-based unions are common, many union activities traditionally take place within the company's premises. This often leads to a tension between a labor union's right to conduct activities and the employer's right to manage its property and maintain order. The issue of unauthorized posting of union bills or posters (bira-bari) on company facilities has been a recurring subject of legal dispute. The Supreme Court's judgment on October 30, 1979, in the Kokutetsu Sapporo Untenku (Japanese National Railways Sapporo Operating District) case, is a landmark decision that established crucial legal principles governing such activities, emphasizing the need for employer permission while carving out a narrow exception.

The Setting: A Union Campaign and Workplace Action

The case arose from events during the 1969 "Spring Offensive" (Shuntō), an annual nationwide campaign of concerted labor action. A Union (the National Railway Workers' Union, Kokuro), to which the X employees belonged, was demanding wage increases and opposing a rationalization plan proposed by Y Company (then the Japanese National Railways - JNR), which reportedly included a significant reduction of 165,000 personnel.

As part of its campaign strategy, A Union's national leadership directed its Sapporo regional headquarters to undertake various actions, including the posting of bills. This directive was then cascaded down to local branches and sub-branches, instructing them to carry out the bill-posting.

The X employees, who were officials within their local union structures, acted on this directive. They pasted one to two bills each onto the doors of approximately 300 employee lockers. These lockers were located in a "crew room" or "staff station" (tsumesho), a facility not accessible to the general public and used predominantly by A Union members for breaks and work preparation. The bills themselves were rectangular (approx. 40cm x 13cm), bore the imprint "A Sapporo Local HQ" at the bottom, and had handwritten slogans such as "Oppose Rationalization" in the blank spaces.

Y Company had an existing rule that prohibited the posting of union documents anywhere other than on designated union bulletin boards. When assistant stationmasters (joyaku) witnessed X employees posting the bills, they ordered them to stop. X refused. When the assistant stationmasters then attempted to remove the bills themselves, X reportedly pushed their shoulders or otherwise engaged in minor physical actions to prevent the removal.

Following this incident, Y Company imposed disciplinary sanctions on X, specifically a formal reprimand (kaikoku), which is the lightest form of disciplinary action available. The grounds for the reprimands were violations of Y Company's work rules, including failure to obey supervisors' orders and engaging in other significantly inappropriate conduct. X subsequently filed a lawsuit seeking to have these disciplinary reprimands declared null and void.

The Legal Challenge and Lower Court Divergence

The Sapporo District Court (December 22, 1972) ruled in favor of Y Company. It found that the bill-posting activities by X exceeded the bounds of legitimate union activity and were therefore illegal, upholding the validity of the reprimands.

However, the Sapporo High Court (August 28, 1974) took a different view and overturned the District Court's decision. The High Court, after considering various circumstances of the case, concluded that the bill-posting was a permissible and legitimate union activity. Consequently, it declared the reprimands invalid. This led Y Company to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Ruling

The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's judgment and ultimately ruled in favor of Y Company, thereby upholding the disciplinary reprimands. In its decision, the Court laid down a foundational framework for analyzing the legitimacy of union activities involving the use of company facilities.

1. Employer's Prerogative: Facility Management and Corporate Order (Kigyō Chitsujo)

The Court began by affirming the employer's fundamental right to manage its enterprise.

- It stated that a company, in order to maintain its existence and ensure the smooth operation of its business, integrates its human resources and the physical facilities it owns and manages, establishing a "corporate order" (kigyō chitsujo) to govern its activities.

- The company can require its members (employees) to adhere to this corporate order. As part of maintaining this order and a proper working environment, the employer can generally prohibit the use of its physical facilities for purposes other than those for which permission has been granted, either through general rules or specific instructions.

- If employees violate these rules or instructions, the employer is entitled to order them to cease the offending behavior, restore the facilities to their original condition, or impose disciplinary sanctions in accordance with established rules.

2. Union Use of Company Facilities: Permission is Key

The Supreme Court then addressed the specific issue of unions using company facilities.

- While employees are often permitted to use company facilities, this permission is generally limited to the scope necessary for performing their work under the employment contract and must be exercised in a manner compliant with the established corporate order, unless a specific agreement states otherwise. This does not inherently grant employees the authority to use facilities for other purposes without explicit permission.

- The Court found no basis to conclude that labor unions possess an inherent, guaranteed right to use an employer's physical facilities for their activities. Thus, being an employee or a union member does not, by itself, confer the authority to use company facilities for union activities without the employer's consent.

- The Court acknowledged the practical reality that enterprise-based unions in Japan often rely heavily on using company facilities for their activities. However, it maintained that such use should, in principle, be based on an agreement reached with the employer, for example, through collective bargaining. The mere necessity for the union to use such facilities does not automatically create a right for the union or its members to use them, nor does it impose a duty on the employer to tolerate such unauthorized use.

3. The "Abuse of Rights" Exception (The Core Test for Legitimacy)

This was the central legal test articulated by the Supreme Court for determining the legitimacy of unauthorized use of company facilities for union activities.

- Using company facilities for union activities without the employer's permission is generally an infringement upon the employer's authority to manage its facilities and maintain corporate order.

- Therefore, such unauthorized use is not considered a legitimate union activity.

- The Exception: Such activity can be deemed legitimate only if there are "special circumstances where refusing permission for such use would constitute an abuse of the employer's rights" over its physical facilities. This is the critical qualification to the general rule requiring permission.

4. Application of the Principles to the Sapporo Bill-Posting Incident:

The Supreme Court meticulously applied this framework to the specific facts of the case:

- The lockers on which the bills were posted were Y Company's property and constituted part of its physical facilities. Employees were permitted to use the lockers for personal storage related to their work, but not for posting bills. A Union was also aware of the rule prohibiting posting documents outside its designated bulletin board, which, at the time, had no space for these bills. Thus, X had no authority to post these bills on the lockers.

- The Court noted that the posted bills were immediately visible to employees using the crew room and, as long as they remained posted, would continuously convey the union's message related to the spring labor offensive.

- Considering these points, Y Company's decision not to permit the bill-posting was deemed a justifiable measure from the perspective of maintaining a proper and orderly working environment, consistent with its business objectives (which included the efficient operation of railway services for public welfare).

- Crucially, the Court found that Y Company's refusal to allow the bill-posting did not constitute an abuse of its rights over its facilities.

- The Court acknowledged several factors argued by the employees: that the bills' content was not defamatory or otherwise inappropriate, that removable tape was used, that the room was not accessible to the public, and that Y Company's primary business operations were not directly or concretely obstructed by the bill-posting. However, it concluded that these circumstances were insufficient to alter its fundamental finding that the company's refusal was not an abuse of rights.

- Therefore, X's bill-posting activities were held to be an infringement of the employer's managerial authority over its facilities and a disturbance of corporate order, and thus could not be considered legitimate union activities. The supervisors' orders to stop the bill-posting were, consequently, not unlawful or improper.

- X's actions, including openly disobeying their superiors' repeated orders and offering some physical resistance, were found to fall within the disciplinary grounds stipulated in Y Company's work rules (specifically, "failure to obey a superior's orders" and "other significantly inappropriate conduct").

- Given that a reprimand is the lightest form of disciplinary action, the Court found that Y Company's decision to issue reprimands was not an abuse of its disciplinary power.

Significance and Implications of the Judgment

The Kokutetsu Sapporo Untenku judgment is a seminal decision in Japanese labor law regarding union activities on company premises.

- Establishment of the "Permission Principle" with an "Abuse of Right" Exception: The case firmly established the general legal principle that union activities involving the use of an employer's physical facilities require the employer's permission. However, this is not an absolute power for the employer; it is qualified by the "abuse of rights" doctrine. If an employer's refusal to grant permission for facility use is deemed, under "special circumstances," to be an abuse of its property or managerial rights, then the union activity might still be considered legitimate. This framework remains highly influential.

- Rejection of the "Duty to Tolerate" Theory: This Supreme Court decision clearly moved away from, and effectively rejected, the "duty to tolerate" (jyunin gimu) theory that some earlier lower court decisions and scholars had supported. That theory argued that employers had a duty to tolerate certain essential union activities on their premises. The Supreme Court instead emphasized employer prerogative, limited only by the abuse of rights doctrine.

- Reinforcement of Employer's Managerial Authority and Corporate Order: The ruling gives substantial weight to the employer's right to manage its property, maintain a suitable working environment, and uphold "corporate order." Unauthorized use of facilities by unions is viewed, in the first instance, as an infringement of these legitimate employer interests.

- "Special Circumstances" as the Narrow Gateway to Legitimacy: The practical effect of this ruling is that the burden of proof often falls on the union or employees to demonstrate the existence of "special circumstances" that would render the employer's refusal to permit facility use an abuse of its rights. The threshold for establishing such circumstances can be high.

- Impact on Workplace Union Activities: This decision, and the legal framework it solidified, has had a significant and lasting impact on how labor unions conduct their activities within company premises in Japan. It underscored the importance for unions to seek permission or negotiate agreements with employers for the use of facilities.

- Precedent for Later Cases: While criticized by some scholars for giving too much deference to employer property rights over union activity rights, the "permission principle" with the "abuse of right" exception has been consistently maintained by the Supreme Court in subsequent cases. However, in some later decisions, particularly concerning activities like leaflet distribution during rest periods in non-work areas (e.g., the M D case ) or union meetings on company premises under specific conditions (e.g., the K G case ), courts have found "special circumstances" warranting the legitimacy of the union activity even without explicit prior permission. This demonstrates that the framework, while generally favoring employer prerogative, does allow for a degree of flexibility depending on the specific facts, the nature of the activity, the degree of disruption, and the availability of alternatives for the union.

Conclusion

The Kokutetsu Sapporo Untenku Supreme Court judgment remains a cornerstone in Japanese labor law concerning the use of company facilities for union activities. It established that while employers generally have the right to control their property and maintain corporate order, thereby requiring unions to seek permission for facility use, this right is not absolute and is subject to the "abuse of rights" doctrine. The decision highlights the delicate balance that Japanese labor law seeks to strike between protecting an employer's managerial and property rights and ensuring that labor unions can conduct essential activities. The precise application of the "special circumstances" exception continues to be a key area of focus in disputes over union activities on company premises.