Unfiled Overpayment Claims in Corporate Reorganization: Supreme Court Upholds Extinguishment, Rejects Abuse of Rights

Date of Judgment: December 4, 2009 (Heisei 21)

Case Name: Claim for Return of Unjust Enrichment, etc.

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

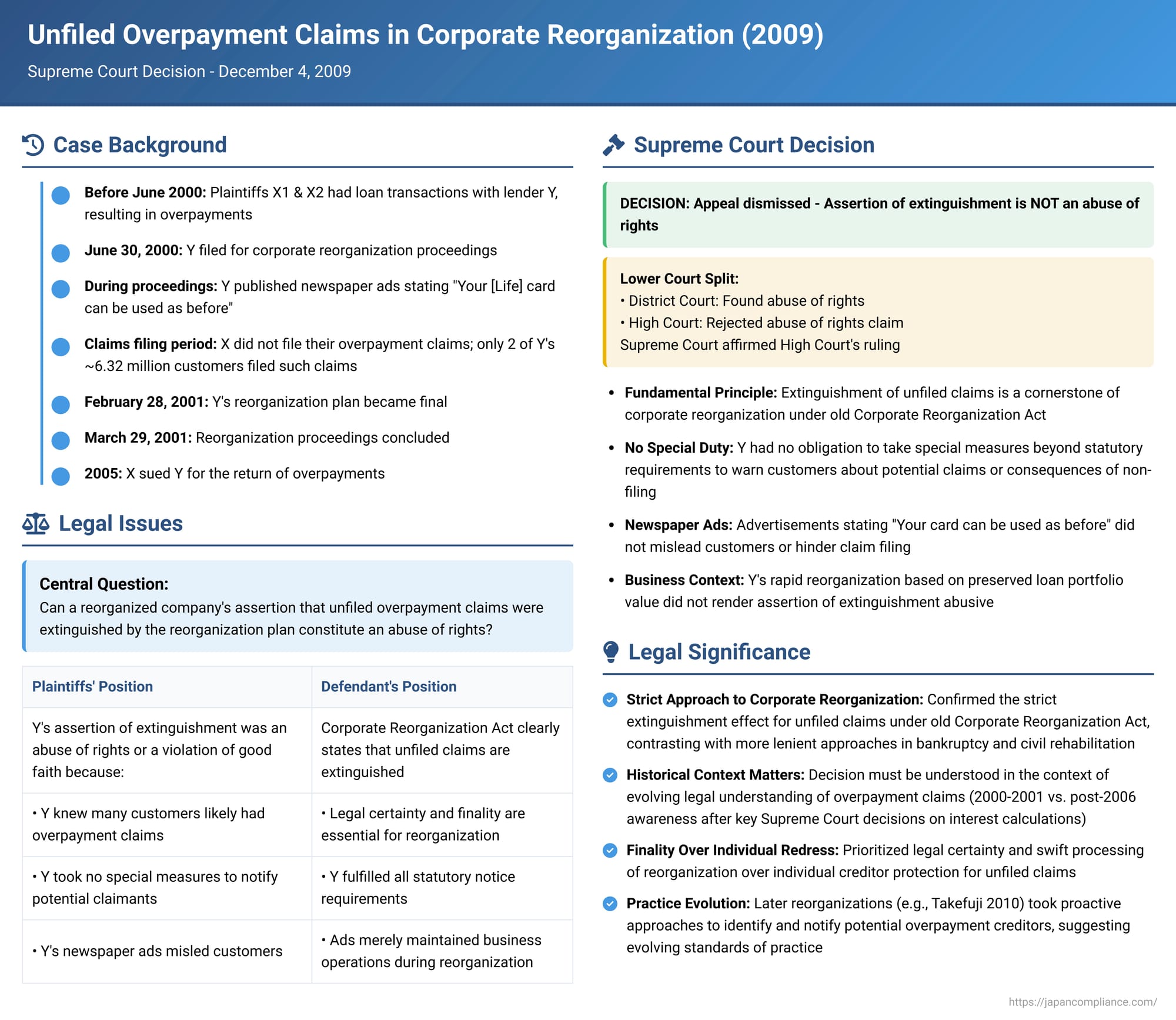

This blog post examines a 2009 Supreme Court of Japan decision concerning the fate of unfiled claims for the refund of overpayments (過払金返還請求権 - kabarai-kin henkan seikyūken) in a corporate reorganization proceeding. The central issue was whether a reorganized company could assert that such unfiled claims were extinguished by the confirmed reorganization plan, and whether such an assertion could be challenged by creditors as an abuse of rights or a violation of good faith, particularly if the company was aware of potentially numerous such claims.

Facts of the Case

The plaintiffs, X1 and X2 (collectively X, appellants before the Supreme Court), had engaged in ongoing loan transactions with Y, a money lending company (defendant/appellee, the company that underwent reorganization). These transactions, when recalculated according to the Interest Restriction Act, revealed that X had made overpayments to Y, giving rise to claims for their refund. These overpayment claims existed before Y commenced corporate reorganization proceedings on June 30, 2000.

X did not file these overpayment claims during Y's corporate reorganization proceedings. Y's reorganization plan was confirmed by the Tokyo District Court on January 31, 2001, and this confirmation became final on February 28, 2001. In March 2001, Y made lump-sum payments to reorganization creditors according to the plan, and the reorganization proceedings were declared concluded on March 29, 2001. The plan provided for a payout of over 54% to general reorganization creditors .

In 2005, several years after the conclusion of Y's reorganization, X filed a lawsuit against Y seeking the return of the overpayments. Y defended by asserting that X's claims, having arisen before the commencement of reorganization and not having been filed in the proceedings, were extinguished by virtue of Article 241 (main text) of the old Corporate Reorganization Act (Act No. 154 of 2002, prior to its full amendment, hereinafter "old Act"). X countered, arguing that Y's assertion of this statutory extinguishment (shikken) constituted an abuse of rights or a violation of the principle of good faith.

Lower Court Rulings

- First Instance (Kyoto District Court): The District Court ruled in favor of X, finding Y's assertion of claim extinguishment to be an abuse of rights. The court noted several factors:

- Shortly after filing for reorganization, Y's then-administrator placed newspaper advertisements stating, "Your [Life] card can be used as before," aimed at preventing customer defections.

- Y had approximately 6.32 million cardholders at the time, yet only two creditors filed claims for overpayments, even though nine such lawsuits were pending against Y around the time of its filing. This suggested Y was aware of potentially numerous unfiled overpayment claims.

- The court reasoned that Y should have taken special measures to inform these potential creditors about the need to file claims and the consequence of extinguishment if they failed to do so. By not doing so, Y benefited from the non-filing, which preserved the value of its loan receivables (a key asset for reorganization) and contributed to a very swift corporate reconstruction with the help of a sponsor, A Co..

- Second Instance (Osaka High Court): The High Court reversed the District Court's decision, ruling in favor of Y and finding no abuse of rights. The High Court emphasized that the old Corporate Reorganization Act, unlike other insolvency statutes such as the Bankruptcy Act or the Civil Rehabilitation Act, adopted a stricter approach to unfiled claims. Given that corporate reorganizations often involve numerous stakeholders and have a broad societal and economic impact, the old Act prioritized swift and uniform processing by placing the onus of claim filing squarely on creditors and ensuring the certainty of extinguishment for unfiled claims not accounted for in the plan. The High Court concluded that merely being aware of potential unfiled claims and not taking extra-statutory steps to prompt their filing did not render the assertion of extinguishment an abuse of rights, as this would contradict the fundamental structure of the old Act.

X appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal regarding the unjust enrichment (overpayment) claim, thereby upholding the High Court's decision that the claims were extinguished and there was no abuse of rights by Y . (Another part of X's appeal, concerning a tort claim, was dismissed for failure to submit reasons and is not discussed further here).

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Fundamental Principle of Extinguishment in Corporate Reorganization:

The Court began by affirming that when a reorganization plan is confirmed, the company is discharged from all reorganization claims except as provided in the plan or by law (the "extinguishment" effect). This, it stated, is a fundamental principle of corporate reorganization proceedings under the old Act. The old Act provided that even if the reorganizing company knew of unfiled claims, these claims were still extinguished unless specifically provided for by law. Furthermore, claims that creditors failed to file within the deadline due to reasons not attributable to them were also, by default, extinguished.

The Supreme Court interpreted these provisions to mean that the old Act prioritized the certainty of extinguishment for unfiled claims not included in the plan to ensure the swift and uniform processing of the reorganization, recognizing that allowing exceptions would significantly impact the company's reconstruction according to the plan. - No Obligation for Special Warning Measures:

Given this statutory framework, the Court held that, regardless of whether Y's trustee or management was aware, or could easily have become aware, that many customers might have overpayment claims, their failure to take special measures to warn customers about the potential existence of such claims or about the consequence of extinguishment for non-filing did not make Y's subsequent assertion of extinguishment impermissible under the old Act. - Assertion of Extinguishment Not an Abuse of Rights or Bad Faith:

The existence of such circumstances (awareness of potential claims, lack of special warning beyond statutory requirements) does not suffice to characterize Y's assertion of claim extinguishment as contrary to the principle of good faith or as an abuse of rights. This conclusion is not altered by how aware X (the creditors) were of their own overpayment claims. - Effect of Newspaper Advertisement:

The newspaper advertisement stating "Your [Life] card can be used as before," published by Y's administrator, was aimed at preventing customer defection and facilitating a smooth reorganization. This purpose was not improper. The content of the advertisement did not mislead customers into believing they did not need to file claims, nor did it hinder them from doing so. Therefore, the publication of this advertisement did not render Y's assertion of extinguishment an act of bad faith or an abuse of rights. - Other Circumstances:

The fact that Y was able to raise funds using its loan portfolio (whose value was preserved due to few overpayment claims being filed) or that very few overpayment claims were actually filed, thereby contributing to Y's rapid reorganization, also did not alter the Court's judgment on the abuse of rights issue. No other circumstances justifying a finding of abuse of rights were identified.

The Supreme Court thus found the High Court's judgment, which rejected the abuse of rights argument, to be correct.

Commentary and Elaboration

1. The Strict Nature of Claim Extinguishment in Corporate Reorganization

The old Corporate Reorganization Act (Article 241, main text, similar to Article 204 of the current Act) established a strict rule: once a reorganization plan is confirmed, the company is discharged from all reorganization claims (debts arising from pre-reorganization causes) except for those rights specifically recognized in the plan or by the Act itself. This "extinguishment" effect (shikken) is a defining feature of the process.

2. Background: Overpayment Claims and the "Administrative Expense" Argument

The commentary notes that in many similar lawsuits against Y, a common argument by overpayment creditors was that their claims should be treated as "administrative expense claims" (kyōeki saiken) rather than "reorganization claims" (kōsei saiken). Administrative expense claims typically receive preferential treatment and are not subject to the extinguishment rule for unfiled claims. Arguments included that by continuing transactions with customers post-commencement, the trustee had effectively chosen to perform ongoing bilateral contracts, making related claims administrative. However, the first instance court in X's case (and many other lower courts) rejected this, typically finding that loan agreements are essentially unilateral (once the loan is disbursed) and that an overpayment claim is a distinct unjust enrichment claim arising from past transactions, not part of an ongoing bilateral executory contract in the sense required to make it an administrative expense claim. This Supreme Court decision focused on the abuse of rights argument concerning reorganization claims.

3. The Division in Lower Court Precedents on Abuse of Rights

Before this Supreme Court ruling, lower courts were divided on whether a reorganizing company's assertion of extinguishment for unfiled overpayment claims constituted an abuse of rights. Some, like the Kyoto District Court in this case and an Osaka District Court in another, had found an abuse of rights. They often emphasized the company's awareness of potentially vast numbers of unfiled overpayment claims and the lack of proactive, specific warnings to these "latent" creditors beyond standard statutory notices. Conversely, many other decisions, including the Osaka High Court in this case, denied such abuse of rights arguments, stressing the statutory strictness of the old Corporate Reorganization Act.

This Supreme Court decision, along with a subsequent ruling on June 4, 2010 (which reversed an Osaka High Court decision that had found a violation of good faith in a similar case), effectively unified the judicial approach, confirming that overpayment claims are generally reorganization claims and that asserting their extinguishment due to non-filing is typically not an abuse of rights under the old Act.

4. Analysis of the Supreme Court's Reasoning and the Importance of Context

- Comparison with Other Insolvency Laws: The Japanese Bankruptcy Act and Civil Rehabilitation Act offer more explicit protections for certain categories of unfiled creditors. For instance, under the Bankruptcy Act, claims that the bankrupt knew of but failed to include in their list of creditors may not be discharged (Article 253, Paragraph 1, Item 6 of the current Act, similar under the old law). The Civil Rehabilitation Act provides that known unfiled claims that the debtor should have self-reported, or claims that creditors were unable to file for reasons not attributable to them, are generally not extinguished but are modified according to the plan (Article 181). The old Corporate Reorganization Act lacked such specific saving provisions for unfiled creditors based on the debtor's knowledge or the creditor's lack of fault.

- Emphasis on the Purpose of Corporate Reorganization: The Supreme Court's decision implicitly views these differences as intentional, stemming from the overarching goal of the Corporate Reorganization Act: the reconstruction of the company, which often involves complex and large-scale financial restructuring. The Court emphasized that allowing exceptions to the extinguishment of unfiled claims could gravely affect the company's ability to implement its reorganization plan and achieve rehabilitation. The High Court had pointed out that abuse of rights might be found in exceptional circumstances, such as if claim filing was actively prevented by fraud or duress, or if the reorganization was initiated with the primary aim of extinguishing known claims through non-filing.

- Historical Context of Overpayment Claims: A crucial aspect highlighted by the commentary is the historical context regarding the awareness and legal treatment of overpayment claims at the time of Y's reorganization in 2000-2001.

- At that time, the "deemed repayment" (minashi bensai) provisions of the Money Lending Business Act (Article 43, Paragraph 1) were often interpreted by lenders as providing a defense against overpayment claims if certain conditions were met. Y, like other lenders, managed its loan accounts based on the contract interest rates, not anticipating massive overpayment liabilities.

- The surge in overpayment refund litigation and the widespread recognition of these claims as generally valid accelerated significantly only after a series of Supreme Court judgments from 2004 to 2006. These later judgments strictly interpreted the requirements for the "deemed repayment" defense, making it very difficult for lenders to invoke successfully.

- Therefore, judging the conduct of Y's trustee and management in 2000-2001 (when Y's reorganization took place and only 9 overpayment lawsuits were pending against a company with 6.32 million cardholders) by the legal understanding and societal awareness prevalent in 2008 (when the first instance court found abuse of rights) or later would be anachronistic. In 2000, the scale of latent overpayment liabilities was not as widely understood by lenders or insolvency practitioners as it became later.

- Potential for Different Outcomes Today: The commentary suggests that if a similar situation—failure to actively prompt the filing of known mass claims—were to occur under current legal standards and awareness, and considering the Corporate Reorganization Rules enacted in 2003 (which include provisions like Article 42 regarding notification to known creditors), the outcome might not necessarily be the same as in this 2009 decision. For instance, the reorganization of Takefuji (a major consumer lender) commenced in 2010 involved recalculating interest for all customers with transaction histories over the past 10 years and proactively notifying them, resulting in over 910,000 claim filings.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2009 decision underscores the strict nature of claim extinguishment for unfiled claims under Japan's old Corporate Reorganization Act. It held that a reorganized company's assertion of such extinguishment against creditors who failed to file their overpayment claims was generally not an abuse of rights or a violation of good faith, even if the company was aware of the potential for many such claims. The Court prioritized the statutory aim of ensuring the certainty and swiftness of corporate reorganizations. This ruling is also significant for its implicit recognition of the importance of the historical context—particularly the evolving legal understanding of overpayment claims—when evaluating the conduct of parties in insolvency proceedings that occurred in an earlier era.