Unfiled Overpayment Claims in Civil Rehabilitation: Supreme Court Clarifies Effect of Plan and Payment Conditions

Date of Judgment: March 1, 2011 (Heisei 23)

Case Name: Claim for Return of Unjust Enrichment

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

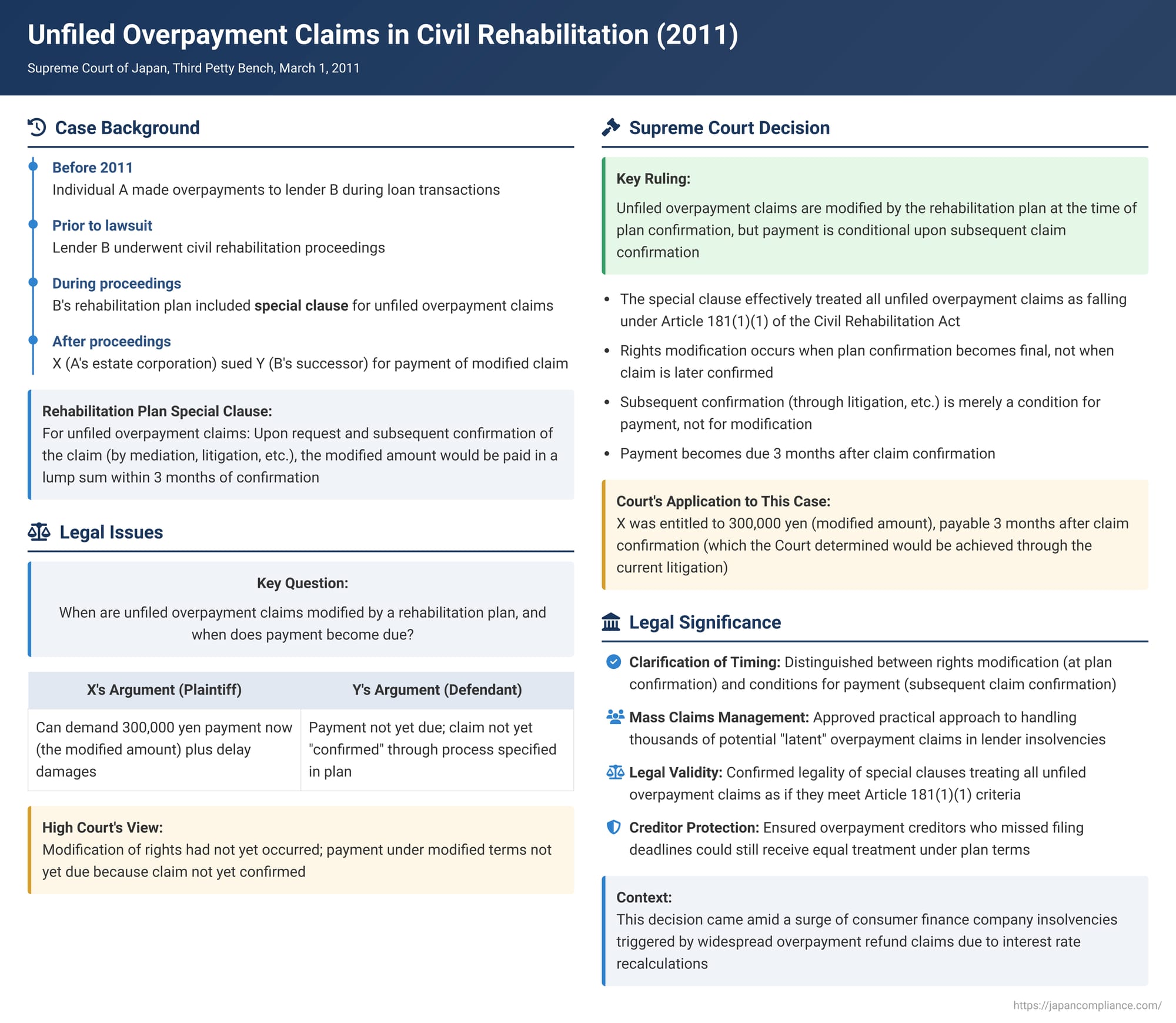

This blog post examines a 2011 Supreme Court of Japan decision that addressed the treatment of unfiled claims for the refund of overpayments (過払金返還請求権 - kabarai-kin henkan seikyūken) made to a lender that subsequently entered civil rehabilitation proceedings. The case is particularly noteworthy for its interpretation of a rehabilitation plan that contained a special clause aiming to address such unfiled claims.

Facts of the Case

The plaintiff, X, was the inherited estate corporation of an individual named A. X sued Y, a company that had succeeded to the rights and obligations of a lender, B, through a company split. The original dispute concerned overpayments A had made to B in the course of loan transactions. B had previously undergone civil rehabilitation proceedings.

B's civil rehabilitation plan included the following provisions for the modification of rights:

- Confirmed rehabilitation claims would be reduced by 60%, with the remaining 40% to be paid in a lump sum within three months of the plan confirmation decision becoming final.

- For "small-amount creditors" with confirmed rehabilitation claims of 300,000 yen or less, the full amount of the claim would be paid in a lump sum within three months of plan confirmation. If the claim exceeded 300,000 yen, the amount to be paid would be the greater of 40% of the claim or 300,000 yen.

- Crucially, for unfiled rehabilitation claims that were overpayment refund claims: Upon a request for payment by such a creditor and the subsequent confirmation of the rehabilitation claim (including its amount, which could be determined through mediation, litigation, arbitration, etc.), the modified amount (as per the general terms above) would be paid in a lump sum within three months from the time the claim was so confirmed.

X (representing A's estate) argued that A's overpayment claim against B fell under this plan, and sued Y (B's successor) for payment of the modified claim amount of 300,000 yen plus delay damages. Y contested the claim, arguing that because X had not yet gone through the process of having the specific overpayment claim "confirmed" as stipulated by the special clause for unfiled claims in the rehabilitation plan, the payment was not yet due, and X could not yet demand it.

Lower Court Ruling

The High Court (original instance court in the appeal to the Supreme Court) had found that, according to B's rehabilitation plan, X's overpayment claim would only be "confirmed" through procedures like litigation (which X was currently pursuing). Therefore, the modification of rights stipulated by the plan, which was predicated on such confirmation, had not yet occurred for X's specific claim. Based on this, the High Court reasoned that Y's defense (that the payment under the plan's modified terms was not yet due) was ill-founded because the claim itself hadn't been formally modified by the plan yet. It partially accepted X's claim, ordering Y to pay 300,000 yen and certain delay damages. Only Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court partially quashed and modified the High Court's judgment, and partially dismissed Y's appeal . Its reasoning differed significantly from the High Court's on the timing of claim modification:

- Statutory Framework for Unfiled Claims:

The Court began by citing key provisions of the Civil Rehabilitation Act:- Article 178 (main text): When a rehabilitation plan confirmation decision becomes final, the debtor is, in principle, discharged from all rehabilitation claims, except for rights recognized by the plan or the Act.

- Article 179, Paragraph 1: The rights of filed creditors, etc., are modified according to the plan's provisions once the plan confirmation is final.

- Article 181, Paragraph 1: When plan confirmation is final, certain unfiled rehabilitation claims—such as those a creditor was unable to file due to reasons not attributable to them (Item 1)—are modified according to the plan's general standards for modification of rights (as per Article 156).

- Interpretation of the Plan's Special Clause for Unfiled Overpayment Claims:

B's rehabilitation plan stipulated that unfiled overpayment refund claims, upon request by the creditor and subsequent confirmation of the claim, would be paid under the same conditions as filed claims. The Supreme Court interpreted this special clause to mean that the plan intended to treat all such unfiled overpayment claims uniformly as rehabilitation claims falling under Article 181, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Civil Rehabilitation Act (i.e., as claims unfiled for reasons not attributable to the creditor). - Effect of Plan Confirmation on These Unfiled Claims:

Consequently, the Court held that these unfiled overpayment refund claims (including X's claim) were modified according to the general standards of B's rehabilitation plan at the time the plan confirmation decision became final. This is a crucial point: the modification of the right itself was not delayed until the creditor made a request or the claim was later formally confirmed. - Condition for Payment (Not for Modification):

The right of the holder of such an unfiled overpayment claim (like X) was to receive payment according to these modified terms. However, the actual receipt of payment was conditioned upon the creditor subsequently establishing the existence and amount of their original overpayment claim (e.g., through litigation, as X was doing). - Payment Due Date Under the Plan:

Based on this interpretation, X's original overpayment claim (calculated as 236,614 yen in principal and 76,538 yen in interest under Article 704 of the Civil Code, totaling 313,152 yen as of the day before B's rehabilitation proceedings commenced) was modified by the plan when its confirmation became final. According to the plan's terms (full payment up to 300,000 yen, or the higher of 40% or 300,000 yen for claims over 300,000 yen), X was entitled to 300,000 yen. This payment would become due three months after X's claim (its existence and amount) was formally confirmed. - Outcome in This Specific Case:

The Supreme Court concluded that X's claim had indeed been modified by the plan, but its payment was conditional. At the time the High Court concluded its oral arguments, the payment was not yet due because the claim had not yet been "confirmed" in the sense required to trigger the 3-month payment period. However, the Supreme Court viewed X's lawsuit as implicitly seeking future payment once the claim was confirmed (which the lawsuit itself would achieve). Given the nature of the case and its procedural history, the Court found it reasonable to order future performance. Therefore, it modified the High Court's judgment to order Y to pay X 300,000 yen (the modified principal) on June 1, 2011 (which was three months after the date of the Supreme Court's judgment, this judgment presumably serving as the "confirmation" of the claim for the purpose of triggering the plan's payment clause), plus delay damages on part of that sum from the day after this future due date .

Commentary and Elaboration

1. Significance of the Decision: Overpayment Claims in Lender Rehabilitations

This case was one of the first major Supreme Court decisions to address the complex issue of handling numerous overpayment refund claims (kabarai-kin saiken) in the context of a consumer finance company's civil rehabilitation. A key feature was the rehabilitation plan's "special clause" designed to deal with overpayment claims that had not been formally filed by creditors during the claims filing period. The commentary focuses significantly on the legality and appropriateness of such special clauses that opt to treat all unfiled overpayment claims as if they fall under Article 181, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Civil Rehabilitation Act (claims unfiled for reasons not attributable to the creditor).

2. Treatment of Overpayment Claims in Rehabilitation Proceedings

- It is undisputed that overpayment refund claims constitute rehabilitation claims (or reorganization claims in corporate reorganization).

- General Rules for Unfiled Claims in Civil Rehabilitation:

- When a rehabilitation plan is confirmed, the debtor is generally discharged from all rehabilitation claims not provided for in the plan (Article 178, Paragraph 1; Article 176).

- Filed claims and claims "self-reported" by a debtor with such an obligation are modified according to the plan (Article 179, Paragraph 1).

- If a debtor has a duty to "self-report" known unfiled claims (under Article 101, Paragraph 3, though this duty does not apply to a trustee), and fails to do so, such unfiled claims are not extinguished but are modified according to the plan's general standards (Article 181, Paragraph 1, Item 3) and are typically paid after the plan's regular payment period concludes (Article 181, Paragraph 2).

- If a creditor fails to file a claim due to "reasons for which the rehabilitation creditor cannot be held responsible" (やむを得ない事由 - yamu o enai jiyū), their claim is also not extinguished but is modified according to the plan's general standards (Article 181, Paragraph 1, Item 1).

- Contrast with Corporate Reorganization: In corporate reorganization proceedings, the rules are stricter; unfiled claims are generally extinguished upon plan confirmation (Corporate Reorganization Act Article 204, Paragraph 1).

- The Special Clause in This Case: B's rehabilitation plan included a special clause to treat all unfiled overpayment claims as if they fell under Article 181, Paragraph 1, Item 1, without individual assessment of whether each creditor truly had a non-attributable reason for not filing.

3. Nature of Overpayment Claims and "Non-Attributable Reasons" for Not Filing

- Overpayment claims arise from recalculating past loan transactions based on the legally permissible interest rates under the Interest Restriction Act. This often reveals that borrowers paid more than legally required, creating a claim for unjust enrichment against the lender.

- Types of Overpayment Creditors:

- Aware vs. Latent: Some creditors are aware they have an overpayment claim ("manifest" or 顕在的 - kenzaiteki creditors), while many are unaware ("latent" or 潜在的 - senzaiteki creditors) until a recalculation is done. Latent creditors, who can number from tens of thousands to millions in large lender insolvencies, pose a significant challenge in insolvency proceedings.

- Transaction-Terminated vs. Transaction-Ongoing: Some creditors' loan transactions with the lender had already ended, while others were ongoing at the time of the insolvency filing.

- Impact of Recalculation: Recalculation not only increases the lender's liabilities (due to newly identified overpayment refund obligations) but also significantly decreases its assets (as outstanding loan receivables are reduced or eliminated, sometimes converting borrowers into creditors). Accurate recalculation across all accounts is essential for determining the insolvent lender's true financial position but can be a massive and time-consuming undertaking. This difficulty impacts not just liability assessment but also the valuation of the lender's primary assets (its loan portfolio). Therefore, in rehabilitating a lender, performing these recalculations is crucial, and proceeding without them is generally problematic.

4. Debtor's Duty to Self-Report Unfiled Overpayment Claims

- If recalculations were not performed for specific reasons, how should unfiled overpayment claims be treated? A key question is whether the debtor (the lender) had a duty to "self-report" (jinin) these unfiled claims under Article 101, Paragraph 3 of the Civil Rehabilitation Act.

- This duty arises if the debtor "knows" of unfiled claims, with "knowing" interpreted to include what could be ascertained with reasonable effort. The underlying basis for this duty is equity.

- For overpayment claims, which are only identified after recalculation, the debtor's duty to self-report hinges on whether such recalculation was reasonably achievable. Factors include the state of transaction records, the need for data entry, and the availability and development time for systems to perform rapid recalculations.

- In B's (Credia's) case, it was determined that its existing claim management system would require considerable time for recalculations, and delaying the rehabilitation process for this would severely diminish business value, making rehabilitation difficult. Therefore, it was considered that B could not "know" the specific overpayment amounts for all latent creditors prior to such extensive recalculation. Consequently, the prevailing view was that B did not have a duty to self-report these latent, uncalculated overpayment claims as "known" unfiled claims.

- Legality of the Special Clause (Treating All as Art. 181(1)(i) Claims): If there's no duty to self-report, the failure of latent creditors to file their claims (often because they are unaware of them) is frequently considered to be "due to reasons for which the creditor cannot be held responsible" under Article 181, Paragraph 1, Item 1. The Supreme Court's decision in this case, along with majority scholarly opinion, affirms the legality of a rehabilitation plan's special clause that treats all such unfiled overpayment claims as falling under this provision, thus preserving them from discharge subject to modification. (This general approach, however, does not necessarily extend to situations where a specific creditor was demonstrably at fault for not filing a known claim ).

- Clarification on the Timing of Rights Modification: The wording of the special clause in B's plan ("rights are modified when the claim is confirmed by litigation, etc.") had caused confusion in lower courts, suggesting that the modification of rights was conditional upon future claim confirmation. The Supreme Court clarified this: the rights modification for these unfiled claims occurred under the general plan terms when the plan confirmation decision became final. The subsequent establishment of the claim's existence and amount through litigation or other means was merely a condition for exercising the right to payment of the already modified claim.

5. Impact and Context of the Decision

- This case arose in a specific socio-economic context: a surge in overpayment refund claims against consumer finance companies, leading to widespread insolvencies. In such situations, identifying all potential (latent) overpayment creditors and the exact amounts of their claims immediately was extremely difficult due to issues with historical transaction records and system capabilities for mass recalculation.

- The Supreme Court's decision to uphold the plan's approach—treating all unfiled overpayment claims uniformly as if they met the criteria of Article 181, Paragraph 1, Item 1—was largely accepted as a pragmatic solution in these extraordinary circumstances.

- The commentary notes that since this case, there have been improvements in recalculation techniques and system development. In subsequent lender insolvencies, it has become more common for comprehensive recalculations to be performed for all potentially affected customers. These advancements may lead to a more nuanced assessment in future cases regarding what constitutes "difficulty in recalculation" and the scope of a debtor's duty to self-report unfiled claims.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2011 decision provided important clarification on how unfiled claims for overpayment refunds are treated under a civil rehabilitation plan that includes specific provisions for them. The Court affirmed that such claims, covered by a plan clause treating them as unfiled for non-attributable reasons, are modified in accordance with the plan's general terms at the moment the plan confirmation becomes final. The subsequent formal establishment of the claim's existence and amount then acts as a condition precedent to the actual payment of this modified claim. This ruling offered a practical framework for dealing with mass latent claims in lender insolvencies, while also underscoring the importance of clear plan drafting and the distinction between the modification of rights and the conditions for their enforcement.