Unfair Share Issuance for Control: Japanese Supreme Court Says "Not Void," Stressing Pre-Issuance Remedies

Judgment Date: July 14, 1994

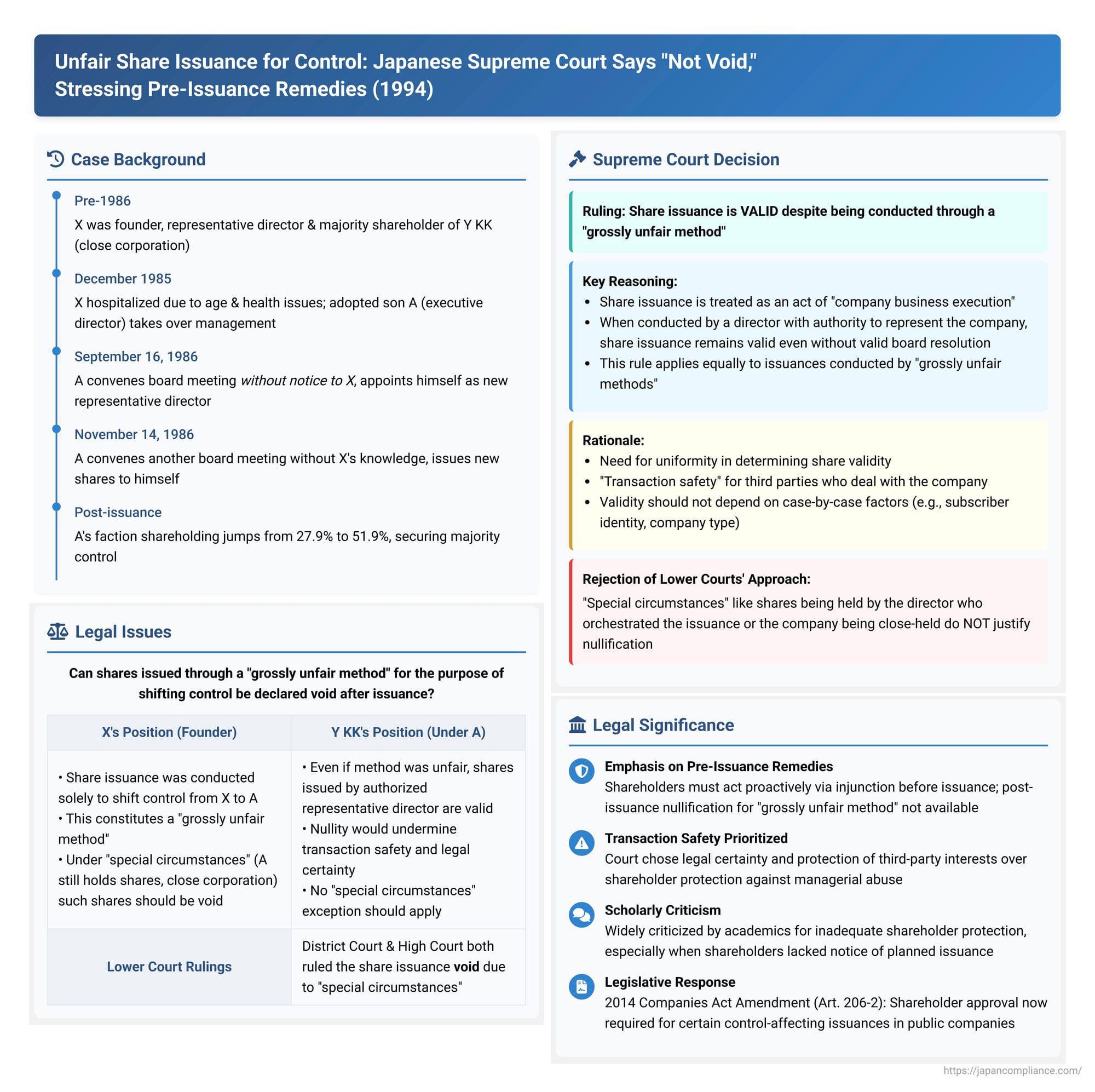

In the often-fraught dynamics of corporate control, a common tactic by incumbent management facing challenges from existing shareholders is to issue new shares to themselves or friendly third parties. This can dilute the influence of opposing shareholders and solidify management's grip on the company. Such share issuances, particularly when motivated by an improper purpose like entrenching control rather than legitimate capital-raising needs, are often described as being effected by a "grossly unfair method." A critical question in Japanese corporate law has been whether shares issued in this manner, after the fact, can be declared void. A landmark 1994 Supreme Court of Japan decision tackled this issue head-on, delivering a ruling that, while controversial, has significantly shaped the landscape of shareholder rights and remedies in such situations.

The Corporate Control Struggle

The case involved Y KK, a company whose articles of incorporation included restrictions on the transfer of its shares. X, the company's founder, had been its sole representative director and held a majority of its shares since its inception. However, due to X's advanced age and declining health, which led to repeated and eventually continuous hospitalization from December 1985, his adopted son, A, who was an executive director, effectively took over the day-to-day management of Y KK.

Over time, the relationship between X and A soured, and A lost X's trust. A grew concerned that X, despite his hospitalization, might convene a shareholders' meeting to pass resolutions detrimental to A's position, such as dissolving Y KK or removing A from the board of directors.

To preempt such actions and seize control of Y KK, A orchestrated a series of maneuvers:

- Change in Representative Director: On September 16, 1986, A convened a board of directors meeting without providing a convocation notice to X (who, despite being hospitalized, was still technically the representative director and a board member). At this meeting, A had himself appointed as the new representative director of Y KK.

- The Disputed New Share Issuance: Subsequently, on November 14, 1986, A convened another board meeting, again without notifying X. This board meeting passed a resolution to issue new shares. This new share issuance ("the Disputed Issuance") was carried out without X's knowledge.

- All the newly issued shares were subscribed to and paid for by A himself. At the time of the lawsuit, A continued to hold these shares.

- The strategic effect of this issuance was significant: the combined shareholding percentage of A and his allies within Y KK jumped from a pre-issuance 27.9% to a post-issuance 51.9%, thereby giving A and his faction majority control of the company.

The Legal Challenge: "Grossly Unfair Method" as Grounds for Nullity

X initiated legal proceedings to nullify the Disputed Issuance. X's primary argument was that the issuance had been conducted through a "grossly unfair method," as its sole purpose was to improperly shift control of Y KK from X to A, to the detriment of X as a shareholder.

- The Court of First Instance (Osaka District Court) found in favor of X and ruled the Disputed Issuance void. The court acknowledged that, as a general principle, a "grossly unfair method" of share issuance might not automatically be a ground for nullity. However, it found that "special circumstances" existed in this particular case. These circumstances included: (a) A, the person who orchestrated the unfair issuance, was also the sole subscriber to the new shares and continued to hold them, meaning there were no immediate concerns about protecting innocent third-party acquirers of these shares; (b) Y KK was a small, closely-held company; and (c) the issuance was demonstrably for the improper purpose of wresting control from X.

- The Appellate Court (Osaka High Court) upheld the District Court's decision, agreeing that the Disputed Issuance was void under these special circumstances.

Y KK, now under A's control, appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: A Controversial Reversal

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated July 14, 1994, reversed the decisions of the lower courts and dismissed X's claim to nullify the share issuance. The Supreme Court held that the Disputed Issuance, despite its potentially unfair nature, was valid.

The majority's reasoning was as follows:

- Nature of New Share Issuance: The Court stated that while a new share issuance is an act related to the company's organization, it is treated analogously to an act of company business execution.

- Effect of Defective Board Resolution on Issuance Validity: Drawing on an earlier precedent (Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, March 31, 1961, Minshu Vol. 15, No. 3, p. 645), the Court reiterated that if a new share issuance is carried out by a director who has the authority to represent the company, the issuance itself is valid even if it lacks a legally effective authorizing resolution from the board of directors.

- "Grossly Unfair Method" Does Not Invalidate an Issued Share: The Court then extended this principle: This rule (that a defective board resolution doesn't nullify the issuance if done by an authorized representative) applies equally even if the new shares were issued through a "grossly unfair method." The fact that a share issuance might be deemed "grossly unfair" (e.g., for an improper purpose) is not, in itself, a ground for nullifying that share issuance after the shares have been issued.

- "Special Circumstances" Argument Rejected: The Supreme Court explicitly rejected the "special circumstances" reasoning adopted by the lower courts. It stated that factors such as the shares being acquired and held by a director who orchestrated the issuance, or the company being small and closely-held, do not alter the conclusion that the share issuance is valid.

- Rationale: Uniformity and Transaction Safety: The Court's primary justification for this stance was the need for uniformity in determining the validity of share issuances. It reasoned that a new share issuance can potentially affect a wide range of legal relationships, including those with third parties (such as company creditors) who deal with the company. Therefore, the validity of an issuance must be assessed according to consistent, objective criteria. It is not appropriate to make this determination on a case-by-case basis, contingent on variable factors like the identity of the subscriber or the size and nature of the company, as this would undermine legal certainty and "transaction safety."

In essence, the Supreme Court concluded that even if A's actions in orchestrating the Disputed Issuance were for an improper purpose (shifting control) and thus constituted a "grossly unfair method," these considerations did not render the already-issued shares void.

Unpacking the Legal Principles and the Court's Stance

This Supreme Court decision drew a sharp distinction between remedies available before a share issuance and those available after:

- Pre-Issuance Injunction (Companies Act Article 210, Item (i)): Japanese company law explicitly allows a shareholder who is likely to suffer a disadvantage to seek a court injunction to stop a company from issuing new shares if the issuance violates laws or the articles of incorporation, or if it is to be done by a "grossly unfair method." X could have (and indeed should have, if aware in time) pursued this remedy before the shares were issued.

- Post-Issuance Nullity Action (Companies Act Article 828, Paragraph 1, Item (ii)): This action allows certain parties (shareholders, directors, etc.) to sue to nullify a share issuance after it has occurred. However, the grounds for nullity are not exhaustively listed in the statute and have been narrowly interpreted by courts to protect transaction safety, generally limited to serious procedural flaws or violations of mandatory law. The Supreme Court, in this 1994 ruling, definitively stated that "grossly unfair method" (improper purpose) is not one of these grounds for post-issuance nullity.

The Court's analogy of share issuance to "business execution" and its reliance on the precedent that even a lack of a valid board resolution doesn't nullify an issuance by an authorized representative have been subjects of considerable academic debate. Critics argue that the power to issue shares is granted to the board primarily for legitimate capital-raising purposes, not to facilitate internal power struggles or serve the personal interests of directors.

Critiques and Scholarly Debate

The Supreme Court's 1994 decision was met with widespread criticism from legal scholars in Japan. Many argued that it prioritized transaction safety to an extent that unduly compromised shareholder protection against managerial abuse, particularly in closely-held companies where the impact of such control-shifting issuances is most acute.

- Inadequacy of Other Remedies: If post-issuance nullity is not available for unfair issuances, shareholders are left with potentially less effective remedies:

- Injunctions: While a powerful pre-emptive tool, obtaining an injunction requires timely action. In closely-held companies, shareholders (especially minority ones) might not receive effective or timely notice of a planned issuance, particularly if management acts secretively, as A did in this case.

- Director Liability: Shareholders could sue directors for damages for breach of their duty of loyalty. However, proving and quantifying the financial loss suffered by individual shareholders due to dilution of control or share value can be exceptionally difficult.

- The "Compromise Theory" Rejected: Many scholars had been advocating for a "compromise" or "eclectic" theory, which the lower courts in this case adopted. This theory suggested that an unfairly issued share should be voidable as long as it remains in the hands of the culpable allottee (like A) or a transferee who was aware of the unfairness. This approach, it was argued, would protect existing shareholders without unduly harming innocent third parties or broader transaction safety. The Supreme Court explicitly rejected this nuanced approach in favor of a more rigid rule of validity.

- "Transaction Safety" Argument: While the Supreme Court emphasized protecting "third parties, including company creditors," critics questioned how significantly the validity of a specific share issuance (especially an internal, control-motivated one) truly impacts the interests of general company creditors in a way that warrants upholding an admittedly unfair issuance.

Reconciling with Other Supreme Court Precedents: The "Injunction-Centric" View

Despite the strong stance in this 1994 case, it's important to view it in the context of other Supreme Court decisions on share issuance validity:

- The Supreme Court has allowed the nullification of new shares when there was a lack of proper public notice or notice to shareholders regarding the issuance, as this deprives shareholders of the opportunity to seek a pre-issuance injunction (Supreme Court, January 28, 1997 – Case 24 in user's context).

- The Supreme Court has also ruled that new shares issued in direct violation of a court-ordered injunction prohibiting that issuance are void (Supreme Court, December 16, 1993 – Case 99 in user's context, the case immediately preceding this one in the user's list).

Some legal commentators attempt to reconcile these decisions by proposing an "injunction-centric" interpretation of the Supreme Court's jurisprudence. Under this view, the Supreme Court prioritizes resolving disputes about the legality and fairness of new share issuances before the shares are issued, through the mechanism of shareholder injunctions. A post-issuance nullity action is then seen as an exceptional remedy, available primarily when the pre-issuance injunction system itself has failed to function as intended (e.g., because shareholders were not given proper notice to seek an injunction, or because an injunction, once obtained, was defied by the company). If an injunction could have been sought (i.e., proper notice was given, and there was no outright defiance of an existing order), then even an issuance by a "grossly unfair method" (as in this 1994 case) would stand, and shareholders would be relegated to other remedies like damages claims against directors.

This interpretation, however, has its own limitations, particularly concerning the effectiveness of notice requirements (e.g., mere Official Gazette notice might be insufficient for shareholders in closely-held companies to act in time).

Scope and Future Outlook

- Primarily a "Public Company" Problem (in a sense): Y KK, despite being closely-held in terms of share distribution, was a "public company" (kōkai kaisha) as defined by the Companies Act (meaning it did not have transfer restrictions on all classes of its shares). For true "non-public companies" (where all shares are subject to transfer restrictions), the Companies Act generally requires a special shareholder resolution for any third-party allotment of new shares (Articles 199(1), 199(2), 309(2)(v)). The absence of such a fundamental shareholder approval is a recognized ground for nullity (Supreme Court, April 24, 2012 – Case 26 in user's context). Thus, the specific issue of a board unilaterally pushing through an unfair issuance primarily for control purposes, as seen in this 1994 case, is more acute in "public companies" where boards have greater default authority over share issuances. The Supreme Court stated that the company's small size or closed nature does not change its conclusion.

- Impact of 2014 Companies Act Amendment (Article 206-2): A significant development since this 1994 ruling is the introduction of Article 206-2 in the 2014 amendments to the Companies Act. This provision now requires shareholder approval (under certain conditions, even a majority vote of minority shareholders) for third-party allotments of shares in listed public companies if such an allotment results in a significant dilution and a change of control, and the acquirer does not conduct a tender offer. Failure to comply with these new procedures could potentially be a ground for nullifying such share issuances (a recent Tokyo District Court decision has found so). This legislative shift, emphasizing shareholder approval for certain control-affecting issuances, might lead to a re-evaluation of the underlying rationale of the 1994 Supreme Court decision in future cases, as it signals an increased legislative focus on shareholder consent in control-related equity issuances.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's July 14, 1994, decision remains a highly significant and widely debated ruling in Japanese corporate law. It firmly established that a new share issuance conducted through a "grossly unfair method," such as for the primary purpose of altering corporate control, is not, in itself, a sufficient ground to nullify those shares once they have been issued. The Court prioritized the need for uniform determination of share validity and broader transaction safety, effectively channeling shareholders aggrieved by such unfair issuances primarily towards seeking pre-issuance injunctions. While this provides a clear rule, it has been criticized for potentially weakening shareholder protection against managerial misconduct in share issuances, especially in situations where obtaining a timely injunction is difficult. Subsequent legislative changes and evolving judicial interpretations continue to shape this complex area of corporate governance and shareholder rights.