Unfair Majority Rule in Partnerships: When Can a Minority Partner Force Dissolution? A Japanese Supreme Court Landmark

Judgment Date: March 13, 1986

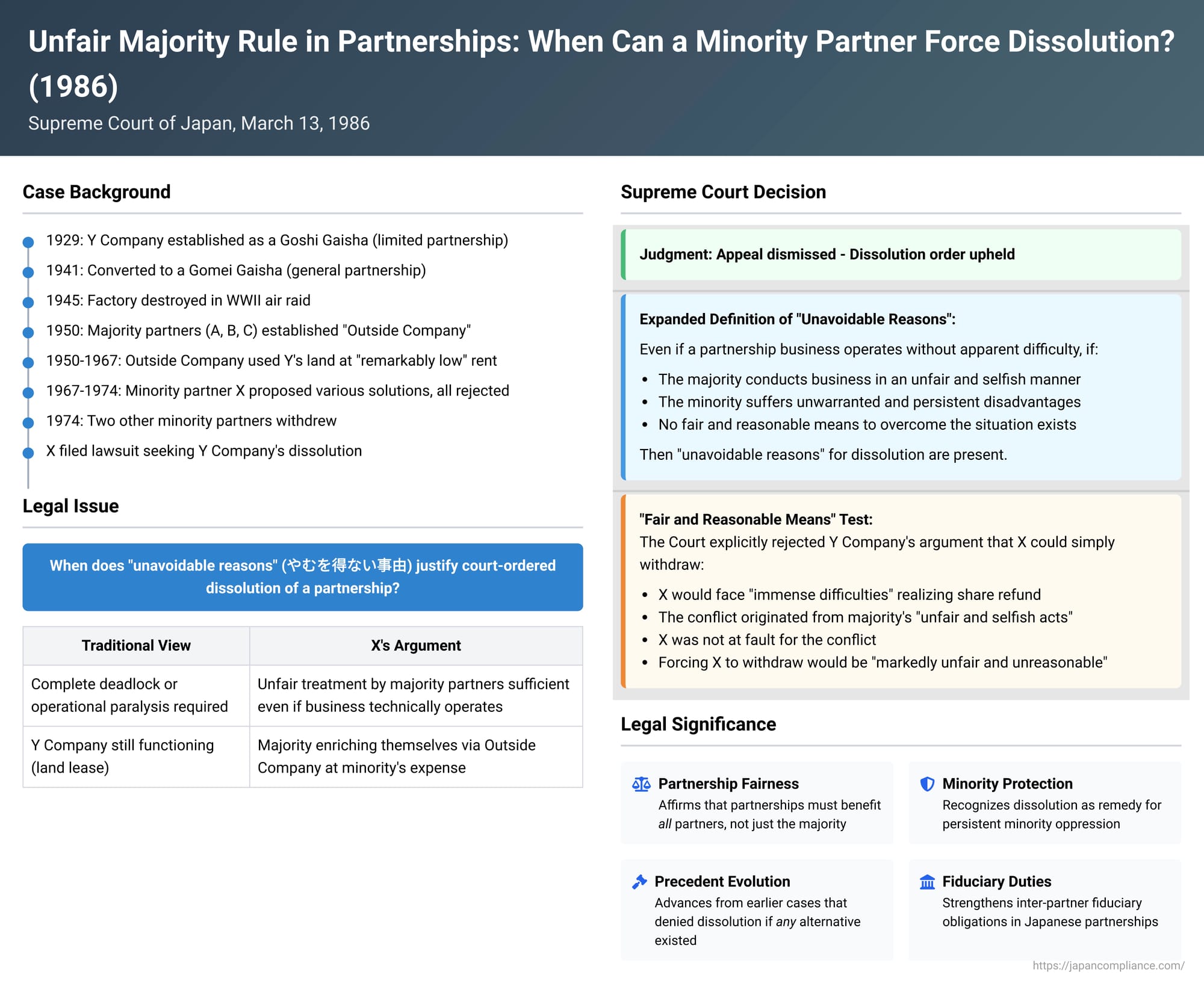

Japanese general partnerships, known as Gomei Gaisha, are fundamentally built on a foundation of strong personal trust and cooperation among partners. However, when this trust breaks down and conflicts arise, particularly between a majority and a minority faction, the law provides an ultimate remedy: a partner can petition the court for the company's dissolution due to "unavoidable reasons" (yamu o enai jiyū). A significant Supreme Court of Japan decision, delivered on March 13, 1986, delved deeply into what constitutes such "unavoidable reasons," especially in situations where a majority of partners conduct the business unfairly and selfishly to the detriment of the minority, even if the company is, on the surface, still operational.

The Factual Saga: A Partnership Divided by Changing Fortunes

The case involved Y Company, which had a history dating back to 1929 when it was established as a Goshi Gaisha (limited partnership). In 1941, it transitioned into a Gomei Gaisha (general partnership) and altered its business purpose to operate a joint processing plant for byproducts generated during silk production, primarily serving its partners who were silk manufacturers.

The Second World War brought a dramatic halt to its primary operations when its factory was destroyed in an air raid in 1945. In the aftermath, the interests of Y Company's partners began to diverge sharply:

- The Majority Group: Three partners, A, B, and C, continued their involvement in the silk industry. In 1950, they established a separate entity, referred to in the judgment as the "Outside Company." A, B, and C became representative directors of this Outside Company. Critically, the Outside Company then began using Y Company's most significant asset – its land and buildings – to conduct business activities very similar to what Y Company had previously undertaken.

- The Minority Group: The predecessor of X (the plaintiff in this dissolution case), along with two other partners, D and E, had already ceased their silk manufacturing businesses by this time. They played no part in the formation of the Outside Company and had not consented to Y Company's property being used by it.

As a result, Y Company's own business activities dwindled to almost nothing. Its sole operation became the leasing of its valuable real estate to the Outside Company, but at a rental rate described as "remarkably low" compared to the property's actual value (e.g., for one business year, annual rent was ¥4.68 million on a property valued at ¥140 million). This meager rental income was largely consumed by public taxes, dues, and director's remuneration paid to A (one of the majority partners). Consequently, Y Company generated almost no profit for distribution to its partners, leading to a severe and entrenched conflict of interest between the majority partners benefiting from the Outside Company and the minority partners left with a nearly defunct Y Company.

X, representing the minority interest, had, since around 1967, made various proposals to Y Company to resolve this situation and find a new path for the partnership (such as becoming a subcontractor for a larger firm, developing a bowling alley, selling or dividing the land, or merging Y Company with the Outside Company). However, all these proposals were rejected by the majority.

Meanwhile, the other two original minority partners (or their successors, in the case of D) had formally withdrawn from Y Company in August 1974 and initiated legal proceedings to claim a refund of their partnership shares. This litigation was still pending at the time of X's action. Due to the withdrawal of one of these partners who had nominally been the representative partner, and the ongoing conflict, Y Company was also unable to appoint a new representative partner as required by its articles of incorporation (which mandated unanimous consent).

Frustrated by the deadlock and the ongoing prejudice to the minority's interests, X filed a lawsuit seeking the dissolution of Y Company based on "unavoidable reasons," as stipulated in Article 112, Paragraph 1 of the then-Commercial Code (the predecessor to Article 833, Paragraph 2 of the current Companies Act). Both the court of first instance and the High Court sided with X and ordered the dissolution. Y Company appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Groundbreaking Decision

The Supreme Court, on March 13, 1986, dismissed Y Company's appeal and upheld the dissolution order. In doing so, it provided a nuanced and expanded interpretation of what constitutes "unavoidable reasons" justifying the dissolution of a Gomei Gaisha.

Defining "Unavoidable Reasons" (解散事由 - kaisan jiyū) for Dissolution

The Court acknowledged the traditional understanding of "unavoidable reasons" in the context of a Gomei Gaisha, which, as a "personal company," relies heavily on strong trust and personal relationships among its partners:

- Traditional Ground: Such reasons exist when, due to emotional causes or other factors, the trust relationship among partners is destroyed, leading to a deadlocked state of discord and confrontation. If this makes it difficult to execute the company's business objectives and, as a result, the company and all its partners suffer irreparable harm, then "unavoidable reasons" for dissolution are present, provided no other means exist to overcome this situation.

However, the Supreme Court went further, adding a crucial dimension:

2. Clarified/Expanded Ground for Unfair Majority Conduct: The Court stated that "unavoidable reasons" are not limited to situations of operational deadlock. A Gomei Gaisha exists for the benefit of all its partners. Therefore, even if the company's business is, on the surface, being conducted without apparent difficulty, if there is a conflict between a majority and a minority of partners, and the business operations are conducted by the majority in an unfair and selfish manner, resulting in the minority partners suffering unwarranted and persistent disadvantages, this also constitutes "unavoidable reasons" for dissolution, provided that no fair and reasonable means exist to overcome this situation.

Defining "Fair and Reasonable Means to Overcome the Situation" (打開の手段 - dakai no shudan)

The Court also elaborated on what qualifies as a "means to overcome the situation" that would negate the need for dissolution. It's not enough that any conceivable alternative to dissolution exists. The alternative must be:

- Fair and reasonable to both the partners seeking dissolution and those opposing it.

- This assessment must consider a range of factors, including:

- The causes of the breakdown in trust or the conflict among partners.

- The degree of involvement or fault of the requesting and opposing partners concerning these causes.

- The extent to which the company's business execution and profit distribution have been unfair or disadvantageous to the partners seeking dissolution.

- All other relevant circumstances.

Application to the Facts of Y Company

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found:

- Y Company, although technically engaged in the business of leasing real estate, was clearly in a state where the unfair and selfish business execution by the majority partners was causing persistent, unwarranted disadvantages to the minority partner, X. This, the Court said, met the criteria for "unavoidable reasons" unless a suitable means to overcome the situation existed.

- Y Company argued that such a means did exist: X could simply withdraw from the partnership and claim a refund of X's partnership share. Since the other minority partners had already initiated withdrawal, X doing so would eliminate the basis of the conflict.

- The Supreme Court rejected this argument, finding that forcing X to withdraw was not a fair and reasonable means for several reasons:

- Difficulty in Realizing the Share Refund: Y Company had no significant regular income. To pay X's share refund, Y Company would likely have to sell its sole major asset (the land and buildings). The majority partners, who relied on this asset for their Outside Company's operations, would fiercely resist such a sale. Therefore, X's claim for a share refund would face "immense difficulties and require many years" to be realized, if at all.

- Root Cause of the Conflict: The conflict arose primarily from the "unfair and selfish acts" of the majority partners who, after some partners retired from the silk industry due to changing economic conditions, disregarded the minority's interests. They established the Outside Company, leased Y Company's property to it at a low rent, effectively put Y Company into a dormant state concerning its original business, and provided only nominal profit distributions to the minority.

- Unfair Burden on the Non-Culpable Minority Partner: X was not found to have any particular fault in causing the inter-partner conflict. Forcing X, against X's will, to choose withdrawal and pursue a highly problematic share refund claim would be "markedly unfair and unreasonable."

Since Y Company's proposed "solution" of X's withdrawal was deemed neither fair nor reasonable, and no other means to overcome the detrimental situation existed, the Supreme Court concluded that "unavoidable reasons" for dissolution were present.

Analysis and Broader Implications

This 1986 Supreme Court decision is significant for several reasons:

- Emphasis on Inter-Partner Fairness in Partnerships: The ruling strongly underscores that even if a partnership is technically functioning, the courts will scrutinize the fairness of its operations, especially in the face of majority-minority conflicts. For Gomei Gaisha, which can be dissolved by the unanimous consent of partners (Companies Act Article 641, Item 3), the principle of "enterprise maintenance" (often prioritized in corporate law) may carry less weight than ensuring equitable treatment among partners. If a majority abuses its position, dissolution becomes a viable remedy.

- The "Fair and Reasonable Alternative" Test as a Safeguard: This is a critical element of the judgment. It prevents a majority from deflecting a dissolution request by merely pointing to a theoretically available but practically unjust alternative for the minority. The remedy offered must genuinely and fairly resolve the predicament for all parties involved, considering their respective conduct and the realities of the situation.

- Evolution from Prior Case Law: While earlier post-war Supreme Court decisions had tended to deny dissolution if any alternative existed (such as partner expulsion or withdrawal), this 1986 ruling refines that approach by adding the crucial qualifier that such alternatives must be "fair and reasonable." It acknowledges the core purpose of a partnership – to benefit all partners – and provides recourse when that purpose is subverted by internal oppression.

- Distinction from Stock Corporations: The ruling's direct application is to partnerships (Gomei Gaisha and, by extension, likely Goshi Gaisha where similar principles of inter-partner relations apply). The criteria for judicial dissolution of stock corporations (Kabushiki Kaisha) are significantly stricter, typically requiring severe operational deadlock or substantial harm to the company's existence (Companies Act Article 833, Paragraph 1). Mere unfair treatment or financial disadvantage to minority shareholders, without these more dire consequences for the company itself, is generally not sufficient to dissolve a stock corporation. However, the underlying theme of resolving deep-seated internal conflicts and the consideration of stakeholder impacts in a dissolution scenario share some conceptual common ground. Legal commentators have noted that the stringent requirements for stock corporation dissolution have faced criticism, with suggestions for legislative reform to either ease these requirements or provide more robust alternative remedies for oppressed minority shareholders.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1986 decision in this Gomei Gaisha dissolution case is a landmark for minority partner rights in Japanese partnerships. It clarifies that "unavoidable reasons" for dissolution are not confined to situations of complete business paralysis. When a majority faction systematically operates the partnership in an unfair and self-serving manner, inflicting persistent and unwarranted harm on the minority, the courts will intervene. Dissolution, while a measure of last resort, becomes a justifiable and necessary remedy if no other means exists that can offer a fair and reasonable resolution to all partners involved. This ruling serves as a potent reminder of the fiduciary duties partners owe to one another and the judiciary's role in upholding equity within the partnership structure.