Unfair Labor Practices in Hiring and Restructuring: The JR Hokkaido & JR Freight Supreme Court Case (December 22, 2003)

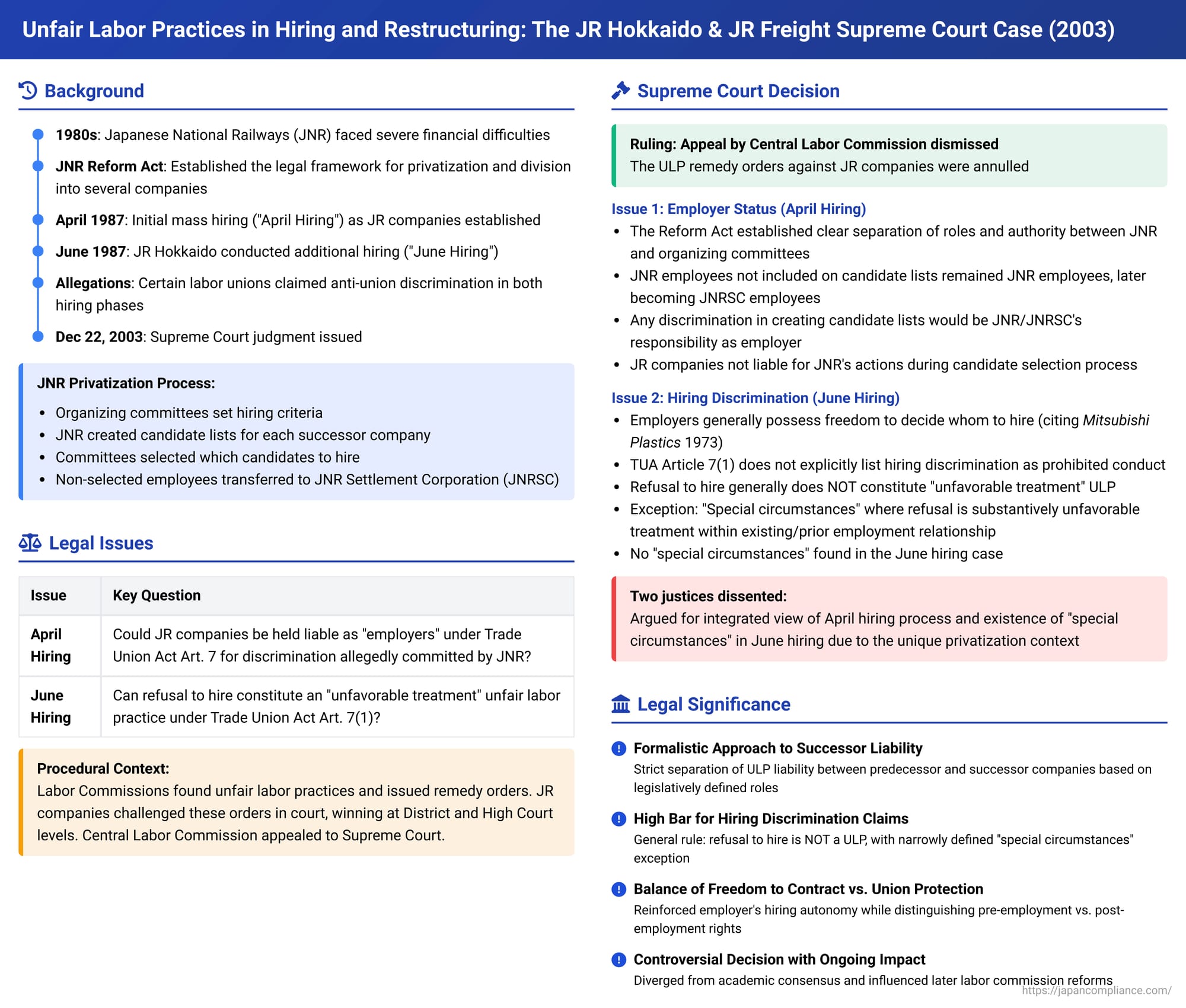

On December 22, 2003, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in a case involving JR Hokkaido and JR Freight (hereinafter "Company Y" or "the JR companies"). This case, arising from the complex privatization of the Japanese National Railways (JNR), addressed two critical issues in unfair labor practice (ULP) law: first, the scope of a successor company's liability as an "employer" for discriminatory acts allegedly committed during the transition process; and second, whether refusal to hire can constitute an "unfavorable treatment" ULP under Japan's Trade Union Act (TUA).

Case Reference: 2001 (Gyo-Hi) No. 96 (Petition for Rescission of Unfair Labor Practice Remedy Order)

Appellant: Central Labor Commission

Appellees (Original Plaintiffs): JR Hokkaido and JR Freight

Judgment of the Supreme Court: The appeal by the Central Labor Commission is dismissed. (This upheld the High Court's decision to annul the ULP remedy orders against the JR companies).

Background: The Privatization of Japanese National Railways (JNR)

The case is set against the backdrop of the monumental privatization of JNR in the late 1980s. JNR, facing severe financial difficulties, was restructured into several private entities, including the JR companies involved in this case. The JNR Reform Act (hereinafter "Reform Act") established a specific, multi-stage procedure for the hiring of JNR employees by these new successor companies:

- Recruitment Initiation: The organizing committees (establishment committees) of the new successor companies would define the terms of employment and hiring criteria, and then recruit JNR employees through JNR itself.

- Candidate List Creation by JNR: JNR would confirm the willingness of its employees to join the successor companies and, based on the criteria set by the organizing committees, select candidates and create a "candidate list for employment" for each successor company. This list was then submitted to the respective organizing committees.

- Final Hiring by Organizing Committees: The organizing committees would then select and notify those on the candidate list whom they decided to hire as employees of the new successor companies, effective from the date of the successor companies' establishment (April 1, 1987).

- JNR Settlement Corporation: JNR employees who were not selected by the successor companies were transferred to the JNR Settlement Corporation (JNRSC), a temporary body established to manage JNR's remaining assets and debts and, crucially, to assist these employees in finding new employment within a three-year timeframe.

The Reform Act also stipulated that actions taken by a successor company's organizing committee, and actions taken towards such a committee, would be deemed actions of, or towards, the successor company itself.

The Disputes Leading to ULP Claims

The ULP claims arose from two distinct hiring phases:

- The "April Hiring": This was the initial mass transfer and hiring of JNR employees into the newly formed JR companies on April 1, 1987. Certain labor unions (including Union K et al., the appellant-intervenors in this case) alleged that their members faced discriminatory treatment, resulting in significantly lower hiring rates compared to members of other unions. They claimed this constituted an unfair labor practice by Company Y.

- The "June Hiring": Subsequently, in June 1987, JR Hokkaido conducted an additional round of hiring to fill vacancies, specifically recruiting from JNR employees who had been transferred to the JNRSC and were based in the Hokkaido region. Again, unions alleged that members of Union K et al. were disproportionately not hired, and that this also constituted a ULP.

The Hokkaido District Labor Commission and, upon review, the Central Labor Commission (CLC) found that ULPs had indeed occurred in both hiring phases. They issued remedy orders, which included directives for the JR companies to re-examine the selection process for certain employees. Company Y then successfully challenged these orders in the Tokyo District Court and subsequently the Tokyo High Court, both of which annulled the Labor Commissions' ULP findings against the JR companies. The CLC then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed the CLC's appeal, thereby siding with Company Y. The Court addressed the two main issues separately:

I. Employer Status for Unfair Labor Practices (April Hiring)

The core question was whether Company Y (the successor JR companies) could be held liable as an "employer" under Article 7 of the Trade Union Act for discriminatory acts allegedly committed primarily by JNR during the creation of the candidate lists for the April hiring.

The Supreme Court reasoned:

- Separation of Roles by the Reform Act: The Reform Act established a clear, phased hiring process, delineating distinct roles and authorities for JNR and the organizing committees of the successor companies. JNR was responsible for creating the candidate lists based on criteria provided by the committees; the committees then made the final hiring decisions from those lists.

- Status of Unlisted Employees: JNR employees not included on the candidate lists created by JNR remained employees of JNR. With JNR's transition into the JNRSC, these individuals became employees of the JNRSC. Their employment relationship continued, albeit in a modified form, with JNR and then JNRSC as their employer. The Court acknowledged that being transferred to the JNRSC placed these employees in a disadvantageous position compared to those hired by the successor companies.

- Liability for Discrimination in List Creation: If JNR engaged in anti-union discrimination during the selection of candidates and the creation of the lists, then JNR (and subsequently the JNRSC as its successor in the employment relationship) would be the party responsible for committing an unfair labor practice (specifically, "unfavorable treatment" under TUA Article 7(1)) against its own employees.

- No Transferred Liability to Successor Companies: The Reform Act, by clearly separating the powers of JNR and the organizing committees at different stages of the hiring process, did not intend for the successor companies (or their organizing committees) to bear ULP liability for discriminatory acts committed solely by JNR in its phase of creating the candidate lists. An exception would be if the organizing committees themselves engaged in ULP. Given the legal framework of the Reform Act, the responsibility for such ULPs committed by JNR rested exclusively with JNR/JNRSC.

The Supreme Court thus concluded that, as the organizing committees themselves were not found to have committed ULPs in the April hiring, Company Y did not bear responsibility as an "employer" for any ULP allegedly perpetrated by JNR during the candidate list creation stage.

II. Hiring Discrimination and Unfair Labor Practices (June Hiring)

The second major issue was whether the refusal to hire certain union members during JR Hokkaido's June recruitment drive constituted an "unfavorable treatment" ULP under TUA Article 7(1).

The Supreme Court reasoned:

- Freedom of Hiring: Citing its earlier landmark decision in the Mitsubishi Plastics case (1973), the Court reiterated the principle that employers generally possess the freedom to contract, which includes the freedom to decide whom to hire and under what conditions, unless specific legal restrictions apply. Once an employee is hired and attains a certain status within the employment relationship, the employer's freedom to unilaterally alter or terminate that status is more restricted than at the initial hiring stage.

- Interpretation of TUA Article 7(1): This provision prohibits employers from dismissing or subjecting employees to "other unfavorable treatment" on account of their union membership or legitimate union activities. The Court noted that the text of TUA Article 7(1) does not explicitly list discriminatory treatment in hiring as a prohibited act within this category of "unfavorable treatment." It inferred that the law distinguishes between the hiring stage and the post-hiring employment relationship stage.

- General Rule on Hiring Refusal as ULP: Consequently, a refusal to hire, as a general rule, does not fall under the definition of "unfavorable treatment" prohibited by TUA Article 7(1). An exception to this would be if there are "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) where the refusal to hire is, in substance, unfavorable treatment within an existing or prior employment relationship, or tantamount to it.

- Application to the June Hiring: The June hiring by JR Hokkaido was conducted after its establishment and was based on its own determination of conditions and personnel needs. The Court characterized this as a new hiring process falling under JR Hokkaido's broad freedom of hiring. It found no "special circumstances" in the refusal to hire certain individuals during this June process that would transform it into the type of "unfavorable treatment" envisioned by TUA Article 7(1).

Therefore, the Court concluded that JR Hokkaido's refusal to hire certain union members in the June recruitment did not constitute an unfair labor practice.

Dissenting Opinions:

It is important to note that two Supreme Court justices issued a dissenting opinion. They disagreed with the majority on both key issues, arguing for a more integrated view of the April hiring process (which would imply successor company liability) and contending that the June hiring did possess "special circumstances" due to the unique context of the JNR privatization and the prior employment relationship of the applicants with JNR.

Analysis and Significance

This Supreme Court judgment, while heavily rooted in the specific legislative framework of the JNR Reform Act, has had broader implications for understanding ULP law in Japan.

- Employer Status in Complex Restructuring (April Hiring):

- The majority's decision to strictly separate the ULP liability of JNR from that of the successor JR companies, based on the letter of the Reform Act, was a focal point of analysis. This contrasted with the Labor Commissions' approach, which had considered aspects like "substantive unity" or viewed JNR as an auxiliary body to the organizing committees to establish JR's liability.

- The PDF commentary is critical of the Supreme Court's formalistic interpretation, noting that it could hinder effective remedies for workers, as JNR and JNRSC were entities with limited lifespans. The dissenting opinion, which emphasized a unified view of the hiring process and took into account parliamentary discussions (where the Minister of Transport described JNR's role as akin to an agent assisting the organizing committees), often finds more support in academic circles. Given the unique statutory context of the JNR Reform Act, the direct precedential value of this part of the ruling for ULP cases outside such specific restructuring laws might be limited.

- Hiring Discrimination as an Unfair Labor Practice (June Hiring):

- The Court's stance on hiring discrimination marked a significant development. By stating that refusal to hire is generally not a ULP under TUA Article 7(1) absent "special circumstances," it set a high bar for such claims. This was based on the established "freedom of hiring" principle and a textual reading of the TUA.

- This ruling diverged from the prevailing academic view at the time, which largely supported the idea that hiring discrimination could indeed constitute a ULP, arguing, for instance, that it undermines workers' rights to organize and that a refusal to hire can be more detrimental than a "yellow-dog contract" (which is explicitly banned).

- The scope of "special circumstances" remains a key question. The PDF commentary suggests that typical examples could include refusal to re-hire seasonal workers or discriminatory non-hiring of former employees during a business transfer or reopening, where a clear pre-existing employment or closely related relationship exists. The Supreme Court’s denial of "special circumstances" in the JNR June hiring, despite the applicants being former JNR employees recently moved to the JNRSC as part of the privatization, indicates a rather strict interpretation of this exception. However, the PDF also notes that if this "special circumstances" requirement is interpreted leniently, it could lead to outcomes closer to the affirmative view on hiring discrimination as a ULP.

- Broader Impact:

The JNR privatization and the ensuing ULP cases, including this Supreme Court decision, had a considerable social and political impact in Japan. The PDF commentary suggests that the series of court rulings overturning Labor Commission orders in the JNR cases may have contributed to discussions and eventual reforms of the Labor Commission system itself, aimed at improving the speed and efficacy of dispute resolution.

Conclusion

The JR Hokkaido & JR Freight case is a complex decision reflecting the tension between specific legislative acts (like the JNR Reform Act), established legal principles (like freedom of hiring), and the protective aims of unfair labor practice law. The Supreme Court's judgment underscored a formal, delineated approach to successor employer liability in the unique context of JNR's breakup. Furthermore, it established a general principle of non-applicability of TUA Article 7(1) to hiring discrimination, allowing for it only under narrowly defined "special circumstances." The strong dissenting opinions and subsequent academic critique highlight the contentiousness and ongoing debate surrounding these interpretations in Japanese labor law.