Undoing the Knot: How Revoking an Appeal Decision Can Invalidate the Original Act in Japanese Administrative Law

Judgment Date: November 28, 1975

Case Number: Showa 49 (O) No. 197 – Claim for Cancellation of Ownership Transfer Registration, Building Removal, and Land Vacation

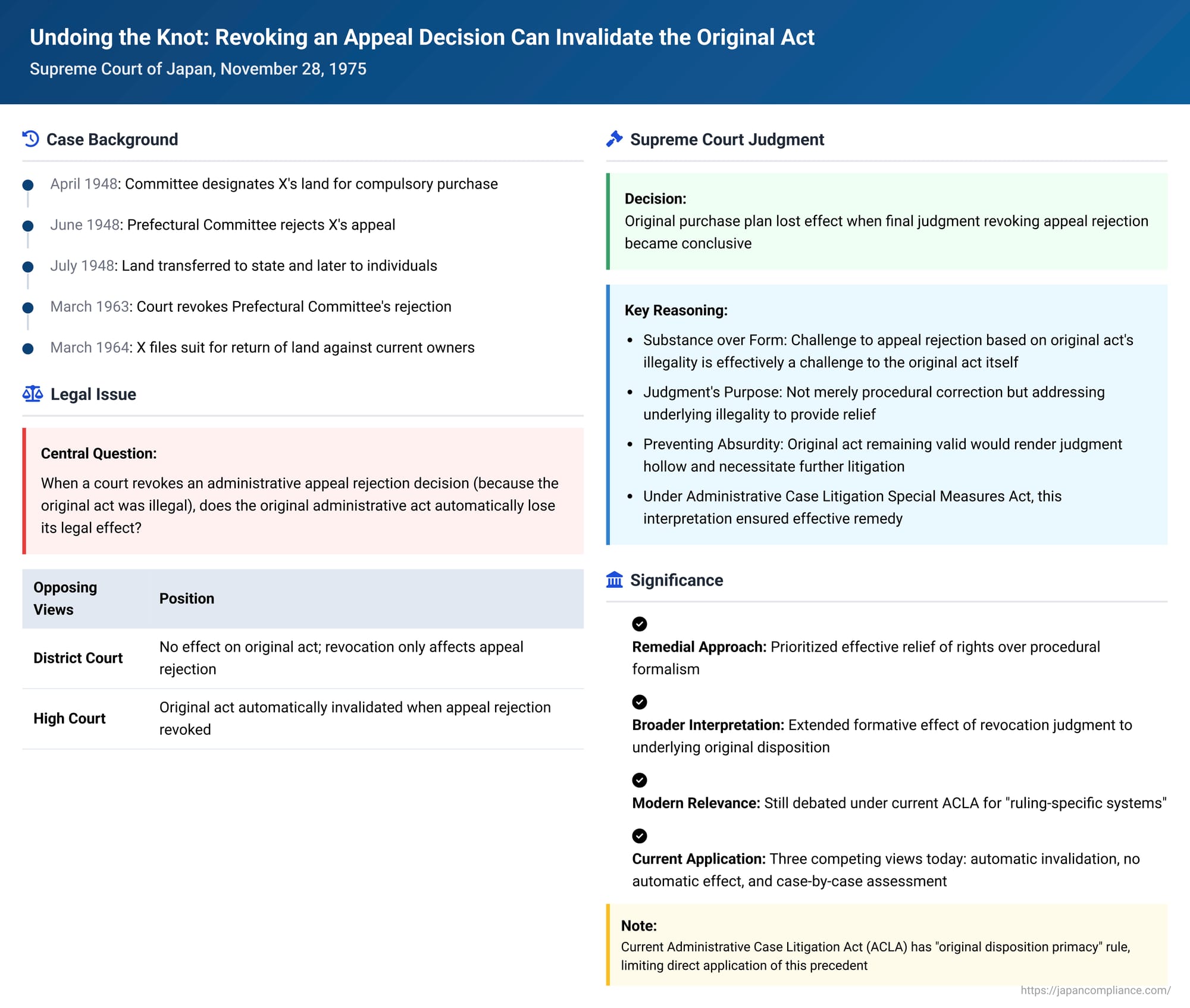

When an administrative decision is challenged through an internal agency appeal, and that appeal is rejected, what happens if a court later revokes the rejection decision because the original government action was flawed? Does this court victory automatically nullify the initial problematic action as well? A 1975 Japanese Supreme Court decision tackled this intricate question, offering a significant interpretation under the legal framework of the time. While the specific legislation has since changed, the Court's reasoning provides valuable insights into judicial efforts to ensure effective remedies.

A Farmland Dispute: The Journey Through Appeals and Courts

The case concerned X, the original owner of a piece of land.

- The Original Action: In April 1948, the Higashisumiyoshi Ward (Osaka City) Farmland Committee designated X's land for compulsory purchase under the Special Measures Act for the Creation of Owner-Farmers, deeming it tenanted farmland.

- Administrative Appeal: X objected to this purchase plan and then filed an administrative appeal (sogan) with the Old Osaka Prefectural Farmland Committee. On June 30, 1948, the Prefectural Committee issued a decision (saiketsu) rejecting X's appeal.

- Litigation ① (The Administrative Suit): X sued in the Osaka District Court to revoke the Prefectural Committee's rejection decision. The grounds for this lawsuit were that the original purchase plan was illegal because X's land was not, in fact, tenanted farmland. After a series of court proceedings, the Osaka High Court, on March 28, 1963, issued a final judgment in X's favor, revoking the Prefectural Committee's rejection decision. This judgment became conclusive.

- Land Transfers: In the interim (July 1948), the land had been formally purchased by the state and sold to an individual, A. By 1961, the land had passed from A to B, and then from B to Y, the defendant in the current proceedings.

- Litigation ② (The Civil Suit): In March 1964, X filed a new lawsuit against Y (the current possessor), B (the intermediate owner), and the State. X sought the cancellation of their respective ownership registrations and the return of the land, arguing that the original purchase plan was void.

The central question in this second lawsuit was the legal effect of the final judgment in Litigation ①. Did the revocation of the Prefectural Committee's rejection decision (because the original purchase plan was illegal) automatically render the original purchase plan itself null and void?

The Lower Courts in Litigation ② Disagreed:

- The Osaka District Court dismissed X's claim. It held that the revocation of the appeal rejection decision only affects that specific decision. The finding that the original purchase plan was illegal was merely a reason within the judgment for Litigation ① and did not, by itself, invalidate the original plan.

- The Osaka High Court reversed this. It ruled that when a court revokes an appeal rejection decision based on the illegality of the original disposition (as was permissible under the old Administrative Case Litigation Special Measures Act), the finding of the original disposition's illegality is not just a passing comment but a matter that acquires res judicata (binding effect). This, the High Court reasoned, binds the relevant administrative agencies. Therefore, the original purchase plan automatically lost its effect without needing a separate revocation order or judgment. Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (November 28, 1975)

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding the Osaka High Court's decision in favor of X. The Supreme Court agreed that the original purchase plan had lost its effect as a result of the judgment in Litigation ①.

Why Revoking the Appeal Decision (on Grounds of Original Illegality) Invalidated the Original Act

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Substance over Form: Under the legal framework of the Administrative Case Litigation Special Measures Act (which was in force at the time of Litigation ① and, unlike the current Administrative Case Litigation Act, did not have a strict "original disposition primacy" rule), a lawsuit challenging an appeal rejection based on the illegality of the original administrative act was, in substance, a direct challenge to the original act itself. It was, in effect, a plea to establish the illegality of the original disposition and eliminate its legal force.

- Purpose of Such a Judgment: When a court upholds such a claim and revokes the appeal rejection decision, its intention is not merely to correct the procedural error of the appellate administrative body. The broader purpose is to address the underlying illegality of the original disposition, annul it, eliminate the unlawful situation it created, and thereby provide relief to the individual whose rights were infringed by that original act.

- Avoiding Absurdity and Injustice: The Court reasoned that if the original disposition were to remain effective despite a judgment revoking the appeal rejection (where the revocation was due to the original disposition's illegality), it would lead to several unreasonable and unjust outcomes:

- The plaintiff's victory in the administrative suit would be hollow and insufficient for actual rights relief.

- It might necessitate further, separate lawsuits to annul the original disposition or require a new administrative act for its cancellation.

- This could lead to overlapping lawsuits, potentially conflicting judgments, and prolonged continuation of the illegal state due to delays in administratively revoking the original disposition.

- New disputes could even arise concerning any new administrative act to revoke the original.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that when the judgment in Litigation ① (revoking the Prefectural Committee's rejection decision due to the illegality of the original purchase plan) became final, the illegality of that original purchase plan was definitively established, and the purchase plan itself lost its legal effect.

The Legal Context: The Old Special Measures Act

It's crucial to understand that this decision was made under the Administrative Case Litigation Special Measures Act. This older law permitted litigants to argue the illegality of an original administrative disposition as a reason for revoking an administrative appeal decision (like a rejection of an appeal). This differs from the current Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA), which in Article 10(2) establishes the principle of "original disposition primacy" (genshobun shugi). This principle generally means that if a direct lawsuit against the original disposition is possible, one cannot challenge the original disposition's illegality within a lawsuit that only targets the appeal decision (unless the appeal decision has its own distinct flaws).

Implications and Significance

While this case was decided under previous legislation, its reasoning about providing effective remedies and addressing the core of a dispute remains pertinent:

- The judgment reflects a "remedial lawsuit theory" (kyūsai soshō setsu), prioritizing the effective relief of rights infringed by illegal administrative actions.

- It represents a broader interpretation of the formative effect of a revocation judgment, extending it to the underlying original disposition in specific circumstances.

Under the current ACLA, the direct scenario of this case (challenging original disposition illegality in a suit against an appeal rejection when a direct suit against the original was possible) is less likely due to Art. 10(2). However, the 1975 Supreme Court's logic is still debated and considered relevant for situations under the current law where a "ruling-specific system" (saiketsu shugi) is adopted by an individual statute. In such systems, only the administrative appeal decision can be challenged in court, even if the true grievance lies with the original disposition. The question then arises: if the appeal decision is revoked because the original disposition was illegal, does the original disposition also lose its effect?

Legal commentary suggests three main views on this issue today:

- Automatic Invalidation (Pro-Extension): Yes, the original disposition also loses its effect, following the reasoning of the 1975 Supreme Court decision for efficient, one-step dispute resolution.

- No Automatic Invalidation (Anti-Extension): No, the revocation of the appeal decision does not automatically nullify the original disposition. This view often relies on ACLA Article 33, Paragraphs 2 and 3, suggesting that the administrative agency whose appeal decision was revoked must now re-adjudicate the appeal.

- Case-by-Case Approach: Whether the original disposition loses effect should be determined individually based on the specifics of the case and the content of the judgment. For example, if a property valuation appeal decision is revoked because the valuation was too high, but the court cannot determine the precise correct value, the original valuation might not be entirely nullified; rather, the assessment committee might need to re-evaluate. However, if the court can determine a specific correct value (partial revocation), the original valuation might be considered modified. If a decision is entirely revoked due to procedural flaws in the appeal process itself, then only the appeal decision is affected, requiring the appeal body to rehear the appeal.

The author of the provided commentary personally supports the case-by-case approach, suggesting that factors like whether the appeal agency needs to re-adjudicate or whether nullifying the original disposition is essential for the plaintiff's relief should be considered. This 1975 Supreme Court decision can be seen as illustrating one scenario where the revocation of the appeal decision did lead to the invalidation of the original disposition.

Concluding Thoughts

The 1975 Supreme Court judgment, though rooted in a past legislative framework, offers enduring insights into the judiciary's approach to ensuring that legal victories in administrative cases translate into meaningful remedies. It underscores a pragmatic desire to resolve the true substance of a dispute and to avoid procedural impasses that would prolong injustice. While the specific application under current law is subject to the "original disposition primacy" rule, the case remains a key reference for discussions on the reach of judicial review and the effects of judgments in multi-layered administrative decision-making processes.