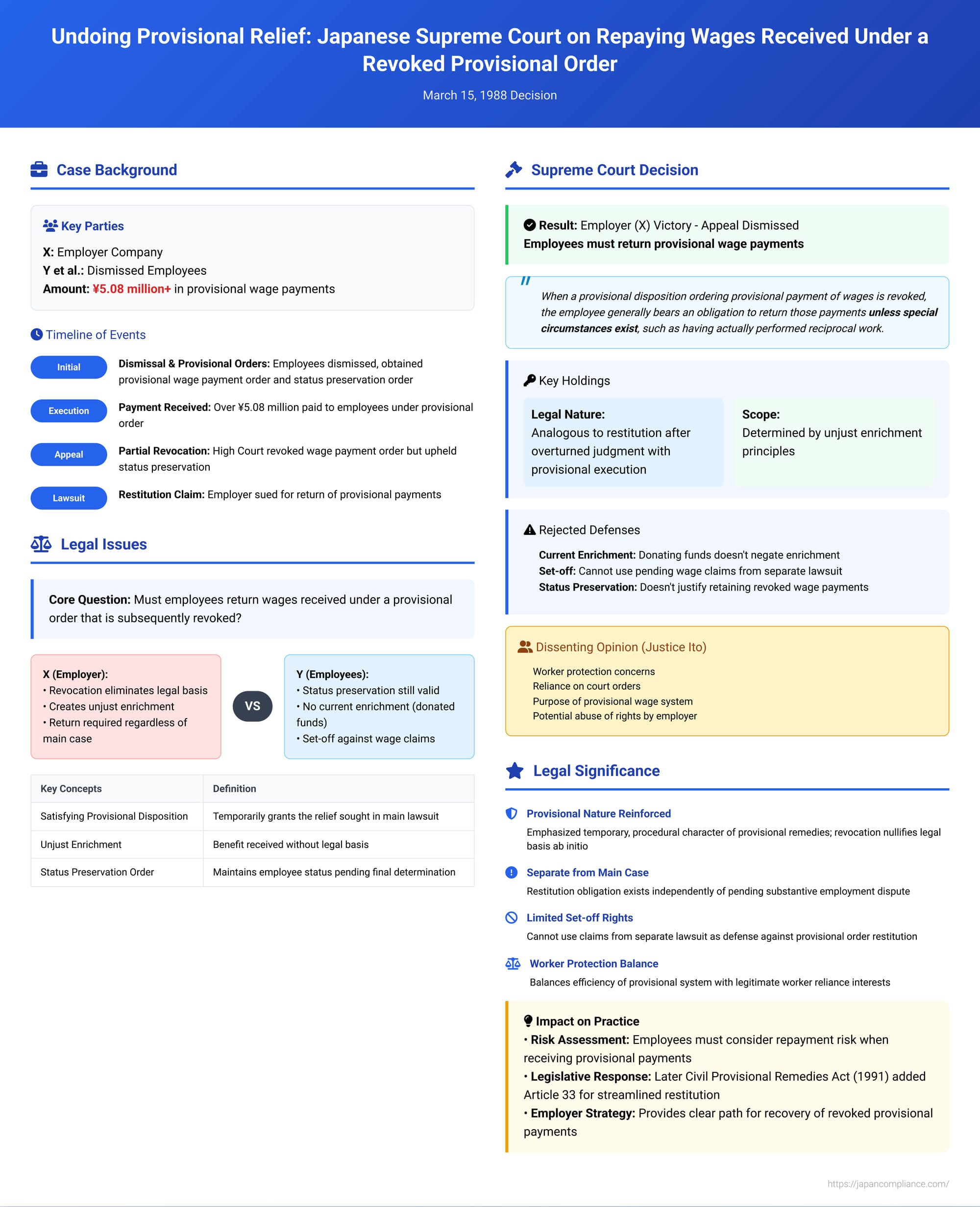

Undoing Provisional Relief: Japanese Supreme Court on Repaying Wages Received Under a Revoked Provisional Order

Date of Supreme Court Decision: March 15, 1988

Provisional remedies in Japan, such as a "provisional disposition for provisional payment of wages" (賃金仮払仮処分 - chingin karibarai karishobun), are designed to provide swift, interim relief to parties, particularly in employment disputes where a dismissed employee might face immediate financial hardship pending the final resolution of their case. These are often "satisfying provisional dispositions" (満足的仮処分 - manzoku-teki karishobun), meaning they provisionally grant the employee the very thing sought in the main lawsuit—payment of wages. But what happens if such a provisional order, after payments have been made under it, is subsequently revoked by a higher court? A landmark 1988 decision by the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan (Showa 58 (O) No. 1406) addressed this critical issue, establishing the general obligation of employees to return such payments and clarifying the legal basis for this restitution.

The Factual Scenario: Dismissal, Provisional Payments, and Partial Revocation

The case involved X, an employer company, and Y et al., employees who had been dismissed by X.

- Initial Provisional Dispositions: Y et al. contested their dismissal, claiming it was invalid. They applied for and were granted provisional dispositions by the court of first instance. These included:

- An order for the provisional payment of wages by X to Y et al.

- An order for the preservation of their employee status (地位保全仮処分 - chii hozen karishobun).

Based on the provisional wage payment order, Y et al. initiated compulsory execution and received payments from X totaling over ¥5.08 million.

- Appellate Review of Provisional Dispositions: Both X and Y et al. appealed the first instance court's decision on the provisional dispositions. In the appellate proceedings, X argued that the necessity for the provisional wage payments no longer existed because Y et al. had subsequently found alternative employment and were receiving wages elsewhere.

The High Court, in its judgment on the provisional dispositions (hereinafter the "Provisional Disposition Appeal Judgment"):- Revoked the first instance court's order for the provisional payment of wages. It accepted X's argument regarding the lack of ongoing necessity due to Y et al.'s new income and dismissed this part of Y et al.'s original application.

- However, it upheld the first instance court's order for the preservation of Y et al.'s employee status.

This Provisional Disposition Appeal Judgment became final and binding.

- Parallel Main Lawsuit: Prior to this appellate judgment on the provisional measures, Y et al. had already filed a main lawsuit against X. In this main lawsuit, they sought a judgment confirming that their dismissals were invalid and claiming payment of unpaid wages. At the time the current restitution lawsuit (initiated by X) reached the stage of concluding oral arguments in its appellate phase, the main lawsuit concerning the dismissals was still pending in its first instance.

- The Employer's Lawsuit for Restitution: Following the High Court's Provisional Disposition Appeal Judgment which revoked the order for provisional wage payments, X (the employer) filed a new lawsuit against Y et al. (the employees). X sought the return of the ¥5.08 million+ that Y et al. had received under the now-revoked provisional wage payment order. (It's noteworthy that this case arose before the current Civil Provisional Remedies Act, which introduced Article 33 providing a mechanism for restitution within the proceedings that revoke a provisional disposition; X's claim was a separate plenary action).

Arguments in the Restitution Lawsuit:

- X (Employer): Argued that upon the revocation of the provisional wage payment order, the legal basis for Y et al.'s receipt of the money disappeared, resulting in unjust enrichment.

- Y et al. (Employees) raised several defenses:

- No Unjust Enrichment: They argued there was no unjust enrichment because their employee status was still provisionally preserved by the upheld status preservation order, and their substantive rights to wages were still being determined in the pending main lawsuit.

- No Presently Existing Enrichment (現存利益 - genzon rieki): They claimed they no longer had the funds, as they had donated the provisional payments received to a third party (their labor union as strike funds – 闘争資金 - tōsō shikin).

- Set-Off (相殺 - sōsai): In the alternative, if they were found liable to return the money, they asserted a right to set off this obligation against their pending claims for unpaid wages being pursued in the main lawsuit.

Lower Court Rulings in the Restitution Lawsuit:

- The court of first instance ruled entirely in favor of X, ordering Y et al. to return the payments.

- The High Court dismissed Y et al.'s appeal and, in fact, allowed X's cross-appeal to expand its claim (likely for interest or other related sums). The High Court reasoned that: (a) provisional wage payments derive from a provisionally formed right, and its revocation renders the payments unjust enrichment; (b) donating the money does not negate "presently existing enrichment"; and (c) asserting a set-off with a claim currently being litigated in a separate main lawsuit is impermissible, by analogy to the rule against duplicative litigation (then Civil Procedure Code Art. 231, now Art. 142).

Y et al. appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Repayment Generally Required

The Supreme Court, in its decision of March 15, 1988, dismissed Y et al.'s appeal, thereby affirming the employer's right to reclaim the provisional wage payments.

Core Holding: The Court established that when a provisional disposition ordering the provisional payment of wages is revoked by an appellate court after the employee (provisional creditor) has received such payments, the employee generally bears an obligation to return those payments to the employer (provisional debtor). This obligation to return arises unless special circumstances exist, such as the employee having actually performed work that stands in a reciprocal relationship to the provisional payments received.

Crucially, this duty to return holds true even if:

- The main lawsuit concerning the validity of the dismissal and substantive wage claims is still pending and undetermined.

- A separate provisional disposition preserving the employee's status remains in effect.

Legal Nature of the Employer's Claim for Return:

The Supreme Court characterized the employer's right to claim the return of these provisional payments as being analogous to the right of restitution that arises when a judgment accompanied by a declaration of provisional execution is subsequently overturned or altered on appeal (as provided for in what was then Article 198, Paragraph 2 of the Code of Civil Procedure, now Article 260, Paragraph 2). This means it's fundamentally about restoring the parties to the position they were in before the (now nullified) provisional execution took place.

However, concerning the scope of the return obligation (e.g., the exact amount, interest, etc.), the Court stated that it should be determined by applying the principles of unjust enrichment (不当利得 - futō ritoku) by analogy. This approach allows for considerations of fairness, taking into account the special, temporary nature of provisional dispositions.

Reasons Underpinning the Return Obligation:

- Provisional and Hypothetical Nature of the Remedy: The Court emphasized that even "satisfying" provisional dispositions, such as orders for provisional wage payments, are inherently temporary and hypothetical (仮定性、暫定性 - kateisei, zanteisei). They do not create final, substantive legal rights or relationships. Their purpose is to create a provisional state of affairs based on a prima facie showing. If such a provisional disposition is subsequently revoked, its legal effects are considered nullified from the beginning (ab initio). Consequently, any payments made under it lose their legal basis, and the situation should, in principle, revert to the status quo ante (the state before execution).

- Procedural Nature of the Provisional Payment Obligation: The employer's obligation to make wage payments under the provisional disposition was a procedural one, specifically formed within and for the purposes of that provisional remedy proceeding. The execution of this provisional order did not mean that the employees' substantive claims to wages were thereby extinguished or satisfied. Therefore, the employer's right to reclaim the provisional payments (upon revocation of the order) is distinct from, and not dependent upon, the ultimate determination of the substantive wage claims being litigated in the separate main lawsuit. The pendency of the main lawsuit does not act as a bar to the employer seeking the return of payments made under a provisional order that has since been specifically revoked.

- Effect of the Separate Employee Status Preservation Order: The Court also addressed the argument that the co-existing provisional disposition preserving Y et al.'s employee status should affect the return obligation. It held that such a status preservation order merely creates a provisional procedural legal status for the employee and primarily anticipates voluntary compliance by the employer (e.g., allowing the employee access to the workplace, not actively treating them as dismissed for certain internal purposes). It does not, by itself, generate an enforceable substantive right to actual wage payments for which no work was performed, particularly when the very existence of the employment relationship is being contested by the employer. Therefore, the continued existence of the status preservation order does not provide a rational basis for allowing the employees to retain wage payments made under a different, now-revoked provisional wage payment order, unless actual work was performed that could be directly attributed to that status and those payments.

"Presently Existing Enrichment" Defense Rejected:

The Supreme Court summarily affirmed the High Court's position on this point. The general principle in Japanese unjust enrichment law is that the benefit derived from receiving money is deemed to persist in the recipient's general assets, even if the specific banknotes have been spent or, as in this case, donated. The act of donating the funds was seen as a disposition of assets by Y et al. at their own responsibility and did not negate the enrichment they had received.

Set-Off Defense Rejected:

The Supreme Court also upheld the lower courts' rejection of Y et al.'s attempt to use their pending wage claims (from the main lawsuit) as a set-off against X's claim for restitution of the provisional payments. The Court reasoned that allowing such a set-off would be problematic because:

- It could lead to duplicative judicial consideration of the wage claims – once in the main lawsuit and again as a set-off defense in the restitution lawsuit.

- It would undermine the specific procedural nature of the restitution claim, which arises directly from the revocation of the provisional order, rather than from a full determination of substantive rights.

- It carried the risk of conflicting judgments between the restitution lawsuit and the main wage lawsuit regarding the validity and amount of the wage claims, potentially harming legal stability. This would contravene the spirit of the rule against duplicative lawsuits (then Article 231 of the Code of Civil Procedure, now Article 142).

- Considering the nature of the wage claims and the ongoing main lawsuit, allowing Y et al. to pursue their claims there while also using them as a set-off defense in this separate restitution suit was not deemed necessary to avoid undue hardship to them.

Justice Masami Ito's Dissenting Opinion: Focusing on Worker Protection and Reliance

Justice Masami Ito dissented, arguing that the case should have been remanded for further consideration of whether Y et al. might have a defense against the full restitution claim. His key points included:

- Purpose of Provisional Wage Payments: The primary objective of such orders is to prevent dismissed workers from falling into severe financial hardship while their main case is pending.

- Effect of Concurrent Status Preservation: When a provisional wage payment order is issued concurrently with an employee status preservation order, employment law principles should apply by analogy to the provisionally formed legal relationship. If the employer (like X) continued to assert that the employment contract was terminated, the employees' obligation to tender labor would be reduced or altered (citing a 1957 Grand Bench precedent).

- Reliance and Good Faith: If the employees, relying on the initial court orders granting both provisional wage payment and status preservation, held themselves ready to perform work (even if the employer refused their services) and refrained from seeking other employment during a certain period, they might have acquired a claim analogous to wages under the doctrine of the employer's default in accepting services (Civil Code Art. 536(2)) or related labor law principles. This could then constitute a defense against the employer's demand for restitution of payments covering that period of reliance.

- Specific Circumstances: Justice Ito noted that the provisional wage payment order was ultimately revoked because Y et al. had later found other employment. The payments they received might have largely covered the period before they secured these new jobs, a period during which the necessity for provisional payments arguably existed, and during which they were acting in reliance on the initial court orders. To force full repayment under these circumstances could be seen as contrary to their reasonable expectations and could potentially undermine the very purpose of the provisional remedy system. He also suggested that the employer's restitution claim might even border on an abuse of rights in this context.

Pre-Civil Provisional Remedies Act Context

It is important to remember that this case was adjudicated under the old Code of Civil Procedure. The current Civil Provisional Remedies Act (CPRA), enacted in 1989 and effective from 1991, introduced Article 33. This article provides a specific mechanism for a court, when it revokes or alters a provisional disposition order due to an objection or changed circumstances, to simultaneously order the provisional creditor to return whatever they received through the execution of the (now-modified or revoked) provisional disposition. This allows for restitution to be handled more efficiently within the same procedural framework. However, legal commentators generally agree that the option of filing a separate plenary lawsuit for restitution, as X did in this case, remains available even under the CPRA. Thus, the principles articulated by the Supreme Court in this 1988 decision regarding the nature of the return obligation and its relationship to unjust enrichment principles continue to be relevant.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's March 15, 1988, decision firmly establishes that wage payments received by employees under a provisional disposition order must generally be returned if that order is subsequently revoked. This obligation is characterized as a form of procedural restitution, with its scope determined by analogy to unjust enrichment principles. The Court clarified that neither the ongoing pendency of a main lawsuit concerning the underlying employment dispute nor the concurrent existence of a separate provisional order preserving employee status automatically negates this duty to return payments made under a specific provisional wage payment order that has itself been nullified. Furthermore, the employees cannot typically use their unresolved substantive wage claims (being pursued in the main lawsuit) as a direct set-off against this restitution obligation.

While the majority opinion emphasized the temporary and procedural nature of provisional remedies, Justice Ito's dissent highlighted important countervailing considerations related to worker protection, reliance on court orders, and the fundamental purpose of provisional wage payments in mitigating hardship. The case underscores the delicate balance courts must strike when provisional relief, intended to be temporary, results in actual transfers of assets that later need to be unwound.