Undoing a Designation: The "Real Child Arrangement" Case and the Power to Withdraw Administrative Acts

Date of Judgment: June 17, 1988, Second Petty Bench, Supreme Court of Japan

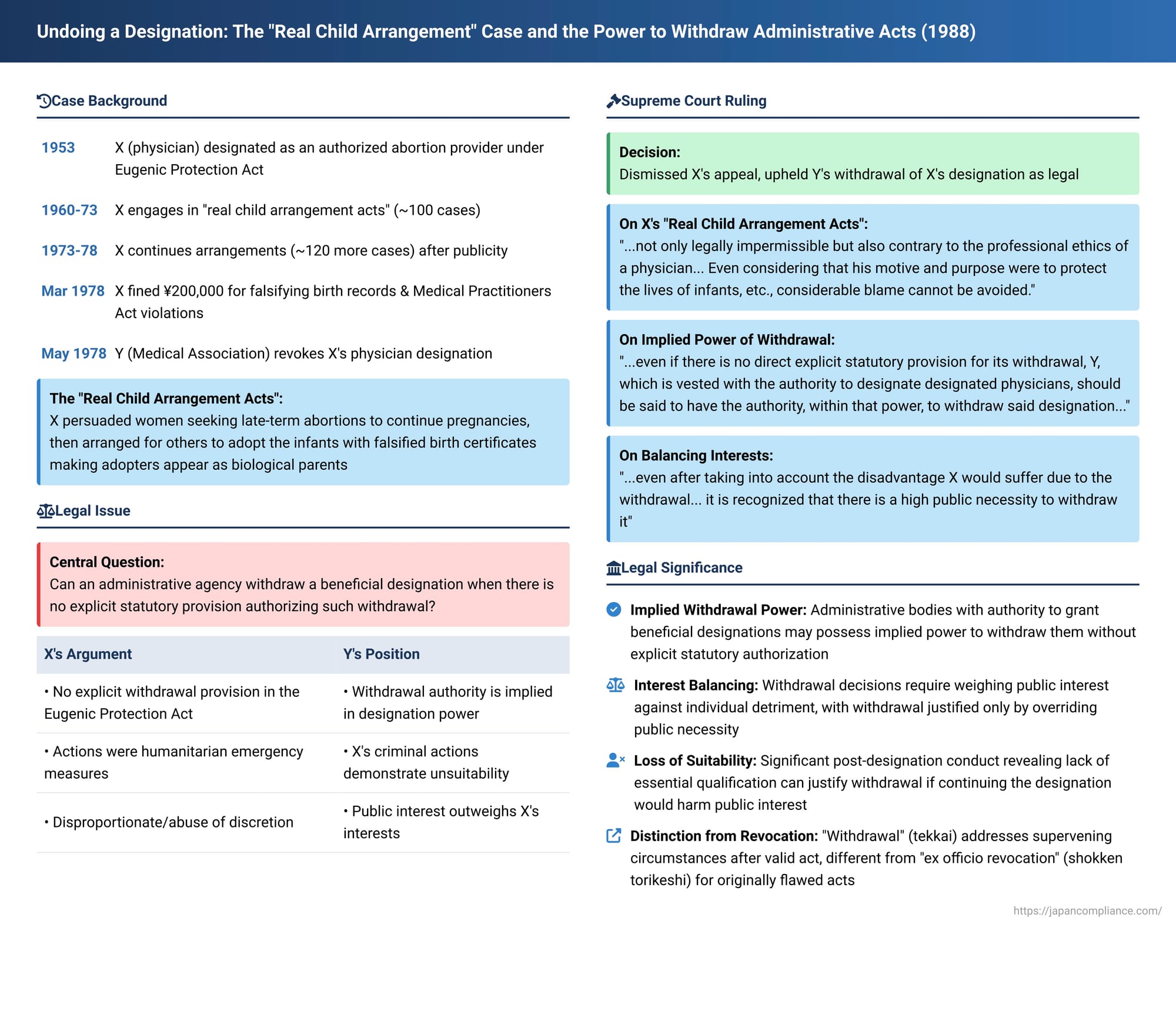

Administrative agencies are often vested with the power to grant beneficial statuses or permits. But what happens if, after such a grant, circumstances arise or actions by the recipient come to light that call into question their suitability or the continued appropriateness of the benefit? Can the agency undo its original decision? This issue, known as the "withdrawal" (撤回 - tekkai) of an administrative act, was at the heart of a significant Japanese Supreme Court case decided on June 17, 1988. The case, arising from the controversial "real child arrangement" activities of a physician, addressed whether an administrative body could withdraw a professional designation in the absence of an explicit statutory provision for such withdrawal, and under what conditions.

The Factual Background: A Doctor, Adoptions, and a Revoked Designation

The appellant, X, was a practicing obstetrician and gynecologist"". In 1953, X was designated by Y, the Miyagi Prefectural Medical Association, as a "designated physician" under Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Eugenic Protection Act (the Act, then in force, later revised and renamed the Maternal Health Act)"". This designation authorized X to perform abortions under the conditions specified by the Act"". X's designation was renewed every two years, with the final renewal occurring on November 1, 1976"".

Between these renewals, X engaged in what became known as "real child arrangement acts" (実子あっせん行為 - jissi assen kōi)"". This practice involved persuading women who sought abortions, often at a late stage of pregnancy, to carry their babies to term"". X would then arrange for these newborns to be given to other women or couples who wished to raise a child, and would falsify birth certificates to make it appear as though the adoptive mother had given birth to the child"". X claimed to have arranged approximately 100 such adoptions before his activities became public knowledge around 1973, and approximately 120 more thereafter"". He asserted that these actions were taken from a humanitarian standpoint as emergency measures to save the lives of infants, particularly in cases where he believed women were past the legal term for abortion but still insistent, until such time as a special adoption law he advocated for was enacted"".

Following a criminal complaint regarding one of these arrangements, X received a summary court order on March 1, 1978, imposing a fine of ¥200,000 for violations of the Medical Practitioners Act and for the offense of making false entries in official documents (birth certificates) and uttering the same"". This criminal disposition became final"".

Subsequently, on May 24, 1978, Y, the Miyagi Prefectural Medical Association, issued a decision revoking X's designation as an authorized physician (the Revocation Disposition)"". The stated reason was that, in light of his criminal conviction and the underlying illegal acts, X was "deemed unsuitable as a designated physician"". X's administrative appeal against this revocation to Y was dismissed in September 1978"". When X reapplied for designation in October 1978, Y rejected this application for the same reasons as the revocation"".

X then filed a lawsuit seeking the annulment of both the Revocation Disposition and the rejection of his re-application. He argued, inter alia, that:

- The Eugenic Protection Act provided for the designation of physicians but lacked any explicit provision authorizing the revocation or withdrawal of such designation, and such a power could not be exercised without explicit statutory basis"".

- Even if Y possessed such a power, his "real child arrangement acts" were undertaken from a humanitarian perspective as emergency measures to save lives, and therefore the revocation was either without valid grounds, disproportionately severe, or an abuse of discretion"".

The first instance court (Sendai District Court) and the second instance court (Sendai High Court) both dismissed X's claims"". They found that Y's judgment that X lacked the personal suitability and character required of a designated physician was not clearly unreasonable, and that even considering the disadvantage to X, there was a higher public interest in revoking the designation"". X appealed to the Supreme Court"".

The Legal Issue: The Power to Withdraw a Beneficial Designation

The central legal question was whether Y, the Prefectural Medical Association, had the authority to withdraw X's beneficial designation as an authorized physician, especially since the Eugenic Protection Act did not explicitly grant such a power of withdrawal. If such a power existed, were the grounds for its exercise in this case legally sound?

This case touches upon the administrative law doctrine of "withdrawal" (tekkai). Withdrawal refers to an administrative act by which an agency extinguishes the future effect of an initially valid administrative act due to the emergence of new facts or circumstances (post-decisional events) that make its continued existence inappropriate or contrary to the public interest. This is distinct from ex officio revocation (職権取消 - shokken torikeshi), which typically refers to the undoing of an administrative act due to a flaw or defect existing at the time the original act was made.

The Supreme Court's Decision of June 17, 1988

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, upholding the legality of the Revocation Disposition"".

1. Illegality and Ethical Breach of X's "Real Child Arrangement Acts"

The Court began by strongly condemning X's actions:

- "Real child arrangement acts undermine the credibility of birth certificates created by physicians, disrupt the order of the family registration system, destabilize the legal status of children by creating false parent-child relationships, and not only circumvent the spirit of Article 798 of the Civil Code (which requires Family Court permission for the adoption of minors) but also carry harms such as the risk of future consanguineous marriage"".

- Furthermore, "consideration was not given to cases where the truth of the parent-child relationship might become an issue for the child in the future, and it must be said that this conduct lacked consideration for the child's welfare"".

- Therefore, "engaging in real child arrangement acts, even if done for the purpose of dissuading women who seek abortion procedures from going through with them, is not only legally impermissible but also contrary to the professional ethics of a physician"".

- The Court found no circumstances that would render X's specific actions an emergency measure or something analogous"".

- "Moreover, X repeatedly and continuously engaged in such real child arrangement acts, unduly downplaying their criminality, the harm they caused, and their social impact. Even considering that his motive and purpose were to protect the lives of infants, etc., considerable blame for the real child arrangement acts performed by X cannot be avoided"".

2. Implied Power of Withdrawal and Its Justification

Addressing the core legal issue, the Court held:

- "After Y... had designated X as a designated physician, it became clear that X lacked the suitability as a designated physician in terms of compliance with the legal order, etc., and a situation arose where continuing X's designation was incompatible with the public interest"".

- "Considering the aforementioned legal problems with real child arrangement acts, the nature of the designation of a designated physician, etc., even after taking into account the disadvantage X would suffer due to the withdrawal of the designation of a designated physician, it is recognized that there is a high public necessity to withdraw it"".

- Consequently, "even if there is no direct explicit statutory provision for its withdrawal, Y, which is vested with the authority to designate designated physicians, should be said to have the authority, within that power, to withdraw said designation with respect to X".

The Court thus affirmed that the Revocation Disposition and the subsequent rejection of X's re-application were not illegal"".

Key Takeaways and Analysis

The Supreme Court's judgment in this case, often referred to as the "Kikuta Doctor Case" or the "Real Child Arrangement Case," is significant for its pronouncements on an administrative agency's power to withdraw a beneficial designation.

1. Affirmation of an Implied Power to Withdraw Beneficial Acts:

A key takeaway is the Court's affirmation that an administrative body vested with the authority to grant a beneficial designation (like Y's power to designate physicians under the Eugenic Protection Act) may also possess an implied power to withdraw that designation if supervening circumstances demonstrate that the recipient no longer meets the requisite qualifications or that their continued holding of the designation is contrary to the public interest"". This power can exist even in the absence of an explicit statutory provision authorizing withdrawal"". This aligns with some legal theories that view the power to grant as encompassing the power to withdraw under certain conditions, or that such a power can be inferred from the overall purpose and structure of the empowering statute"". The Supreme Court itself, in the Chlorokin drug harm case (1995), had similarly inferred a power to withdraw drug manufacturing approval based on the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act's objectives and the Health Minister's overall responsibilities, despite the lack of an express withdrawal clause for that specific type of approval"".

2. Balancing Public Interest Against Individual Detriment:

The decision to withdraw a beneficial administrative act is not unfettered. The Court engaged in a balancing exercise, weighing the "high public necessity" of withdrawing X's designation against the "disadvantage X would suffer" from such withdrawal"". The Court found that the public interest in ensuring that designated physicians maintain suitability, particularly in terms of law abidance and ethical conduct, and in upholding the integrity of legal systems like family registration, outweighed X's interest in retaining the designation, especially given the serious nature of his misconduct"". This balancing approach is consistent with established principles for restricting the withdrawal of beneficial acts, where withdrawal is generally disfavored unless justified by overriding public interest considerations or other specific grounds (such as recipient fault or change of circumstances)"".

3. Grounds for Withdrawal: Loss of Suitability and Public Interest:

The Court's reasoning indicates that a significant change in circumstances occurring after the initial grant of a beneficial act—specifically, the revelation of conduct demonstrating a lack of essential suitability or qualification—can justify withdrawal if continuing the act would be contrary to the public interest"". In X's case, his criminal conviction and the nature of his "real child arrangement acts" were deemed to demonstrate such a loss of suitability to be a physician entrusted with the sensitive responsibilities under the Eugenic Protection Act"".

4. Distinguishing Withdrawal from Ex Officio Revocation:

It is important to note that this case concerns "withdrawal" (tekkai), which addresses supervening facts or circumstances arising after an initially valid administrative act was issued"". This differs from ex officio revocation (shokken torikeshi), which typically deals with rectifying an administrative act that was flawed or illegal from its inception"". The legal basis and conditions for these two types of administrative actions can differ"".

5. The Role of Professional Ethics and Legality:

The Supreme Court placed strong emphasis on the fact that X's actions, irrespective of his claimed humanitarian motives, constituted clear legal violations and breaches of medical professional ethics"". This finding was central to the determination that he had become unsuitable to continue as a designated physician and that there was a compelling public interest in withdrawing his designation"".

Conclusion

The 1988 Supreme Court decision in the "Real Child Arrangement Case" provides important clarification on an administrative agency's authority to withdraw a beneficial designation. It affirms that such a power can be implied from the power to grant, even without explicit statutory authorization, particularly when the continued existence of the designation becomes incompatible with the public interest due to the recipient's subsequent conduct revealing a fundamental lack of suitability. The judgment underscores the principle that the exercise of such withdrawal power, especially for beneficial acts, requires a careful balancing of the public interest against the individual's reliance and potential detriment. In this instance, the gravity of the physician's unlawful and unethical conduct, and the resulting harm to public systems and trust, were deemed to constitute a "high public necessity" justifying the withdrawal of his specialized designation.