Understanding "Working Hours": A Deep Dive into a Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on On-Call Napping Time (February 28, 2002)

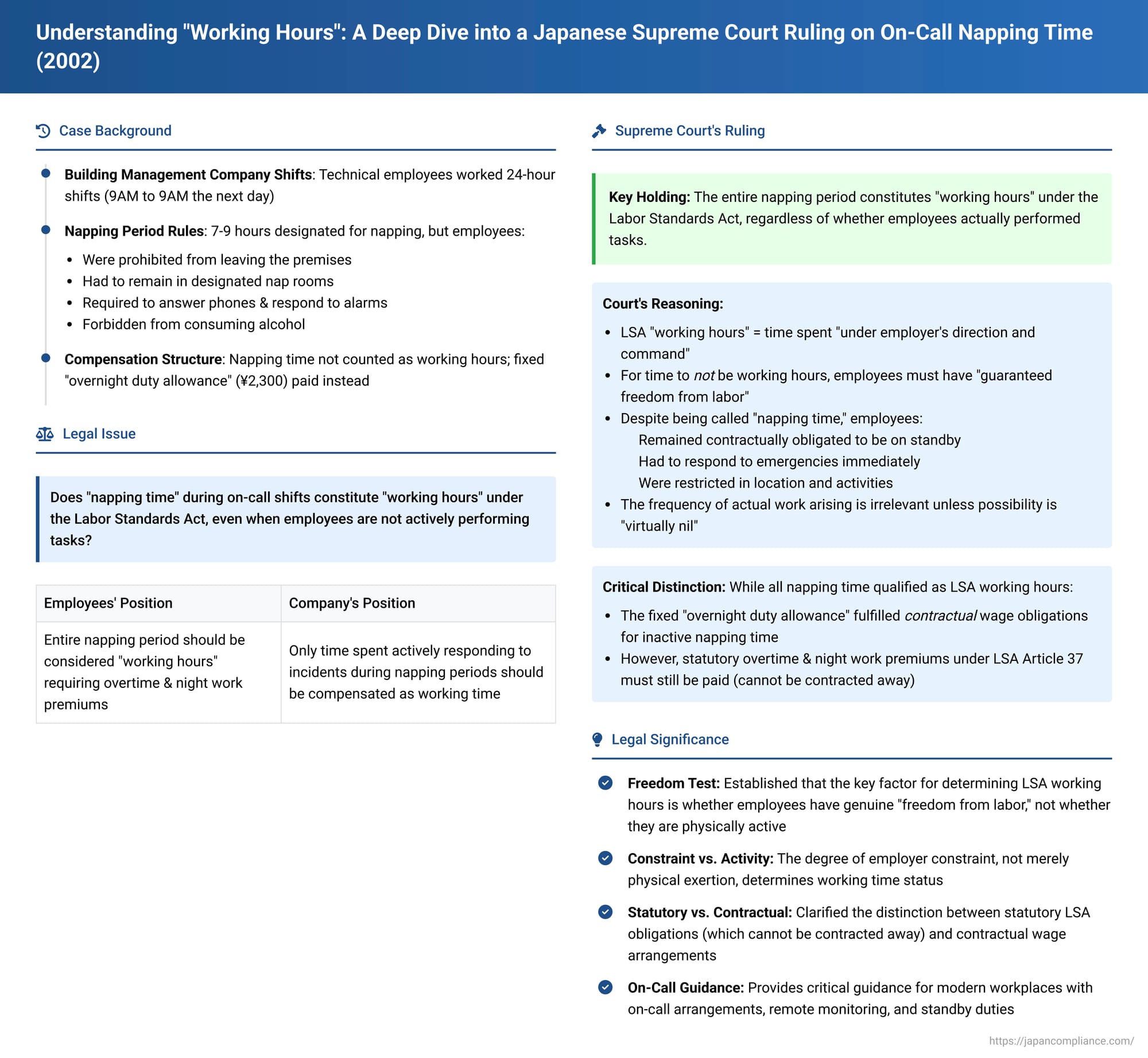

On February 28, 2002, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in an overtime wage claim case. This ruling delved into the crucial question of whether "napping time" provided to employees during extended on-call shifts qualifies as "working hours" under Japan's Labor Standards Act (LSA), thereby potentially entitling them to overtime and other premium payments. The decision offers valuable insights into how Japanese law interprets an employer's direction and command, and the conditions under which on-call or standby time is compensable.

Background of the Case: The 24-Hour Shifts and Napping Periods

The plaintiffs were technical employees of Company Y, a building management firm. Their duties involved operating, monitoring, and maintaining building equipment, conducting patrols, and responding to tenant issues in buildings managed by Company Y.

A key aspect of their work involved periodic 24-hour shifts (e.g., from 9:00 AM one day to 9:00 AM the next). During these extended shifts, employees were allotted approximately two hours of break time and a continuous napping period typically lasting between seven to nine hours.

Crucially, during this napping time:

- Employees were, as a general rule, prohibited from leaving the building premises.

- They were required to remain in designated nap rooms.

- They had an obligation to answer telephones and respond immediately to any alarms or emergencies (e.g., equipment malfunctions, security alerts).

- Consumption of alcohol was forbidden.

Company Y did not count this napping time as part of the employees' scheduled working hours. Instead, employees received a fixed "overnight duty allowance" (in this instance, 2,300 yen for a 24-hour shift). If an employee performed actual, identifiable work during the napping period due to an incident, they were paid separate overtime and/or night work allowances for the specific duration of that active work.

The Legal Challenge: Are We Working While Napping?

The plaintiff employees contended that the entirety of the napping time, irrespective of whether they were actively engaged in tasks, should be recognized as "working hours" under the Labor Standards Act. Based on this, they sought unpaid overtime wages and night work allowances for the napping periods that occurred between February and July 1988. Their claim was primarily based on the terms of their collective bargaining agreement and company work rules, and alternatively, on the statutory provisions for overtime and night work premiums stipulated in Article 37 of the LSA.

The Tokyo High Court, acting as the lower appellate court, found that the napping time was indeed time spent under the employer's direction and command. However, it also concluded that the employment contract implied that, for napping periods without actual work, no overtime or night work pay (beyond the existing overnight duty allowance) was contractually due. Despite this, the High Court did order Company Y to pay statutory overtime and night work premiums for those portions of the napping time that exceeded statutory working hour limits or fell within statutory night work hours. Both parties appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: A Detailed Analysis

The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings, primarily due to errors in calculating overtime. However, its reasoning on the nature of napping time and its relation to working hours and wages is highly instructive.

1. Napping Time as "Working Hours" under the Labor Standards Act

The Supreme Court first addressed whether the napping time, including periods of inactivity, constituted "working hours" as defined by the Labor Standards Act.

- Defining LSA Working Hours: The Court reiterated the established principle that LSA working hours are objectively defined as "time during which a worker is placed under the employer's direction and command." This principle had been affirmed in previous landmark cases.

- Inactive Time and Employer's Command: The mere fact that an employee is not actively performing tasks during a period (like napping) does not automatically mean they are free from the employer's direction and command.

- The "Guarantee of Freedom from Labor": For a period to not be considered working hours, the employee must be guaranteed the freedom to be completely disengaged from work. If such a guarantee is absent, even inactive time can fall under LSA working hours.

- Contractual Obligations During Napping Time: The Court found that if an employment contract mandates the provision of services during a specific time, it signifies that freedom from labor is not guaranteed. In such a scenario, the employee remains under the employer's direction and command.

- Application to the Case: In this instance, the plaintiffs were contractually obligated during their napping periods to remain on standby in the nap rooms and to respond immediately to alarms, telephone calls, or any other work-related demands. Even if the actual need for intervention was infrequent, the Court noted there was no evidence to suggest that the possibility of such occurrences was "virtually nil" (a high bar to meet). The continuous obligation to be ready to respond meant their freedom from work was not truly guaranteed.

- Conclusion on LSA Working Hours: Therefore, the Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's finding on this specific point: the entire napping period, including time spent resting or sleeping without active engagement in tasks, constituted "working hours" under the Labor Standards Act. The employees were not genuinely free from their work obligations.

This part of the ruling underscores that the focus is not solely on physical exertion but on the degree of constraint and the employer's ability to direct the employee. If an employee is required to remain available and responsive, that time is likely to be considered working time, even if it's designated as "napping" or "standby."

2. LSA Working Hours vs. Contractual Wage Entitlements

The Supreme Court then distinguished between time qualifying as LSA working hours and an automatic entitlement to contractual wages for that time.

- LSA Status Doesn't Create Automatic Contractual Pay: The Court clarified that simply because a period is deemed LSA working hours does not, in itself, automatically generate a claim for specific wages prescribed by the employment contract (e.g., contractually defined overtime rates for all napping hours). The entitlement to such contractual wages depends on the specific terms agreed between the employer and employee in their labor contract or outlined in work rules or collective agreements.

- Presumption of Compensation: However, the Court also noted that employment contracts are fundamentally based on an exchange of labor for wages. Therefore, a reasonable interpretation of an employment contract would generally presume that time qualifying as LSA working hours is intended to be compensated in some manner. It would be unreasonable to conclude that LSA working time is entirely unpaid merely because there isn't an explicit, separate wage provision for that specific type of inactive time, especially if general provisions for overtime pay exist.

- Interpreting the Contract in This Case:

- The existing wage regulations and collective agreement at Company Y did provide for overtime and night work allowances if actual work was performed during the napping period.

- Crucially, a distinct "overnight duty allowance" was specifically paid for shifts that included these extended napping periods.

- Considering the employees' monthly salary system and the typically low labor density during the inactive portions of the napping time, the Supreme Court interpreted the employment contract to mean the following: The overnight duty allowance served as the agreed-upon compensation for the entirety of the napping period itself (when no active tasks were performed). If active tasks arose, then additional, separate overtime or night work payments would be made for that active work.

- Conclusion on Contractual Claims: Consequently, the Supreme Court upheld the High Court's conclusion that the plaintiffs could not claim additional contractual overtime and night work pay (based on their work rules or collective agreement) for the inactive portions of the napping time, beyond the already paid overnight duty allowance.

This distinction is critical: while the time was "work" for LSA purposes, the specific contractual agreement on how that particular type of low-intensity work (inactive standby) was to be paid was deemed to be covered by the overnight duty allowance.

3. Statutory Overtime and Night Work Premiums (LSA Article 37)

Despite the finding on contractual wages, the Supreme Court then addressed the employer's statutory obligations under the Labor Standards Act.

- Supremacy of LSA Standards: LSA Article 13 stipulates that any labor contract terms falling below the standards set by the LSA are void in that respect, and the LSA's minimum standards apply instead.

- Mandatory Premiums under LSA Article 37: LSA Article 37 mandates that employers pay premium rates for work performed beyond statutory maximum working hours (overtime) and for work performed during statutory night hours (typically 10 PM to 5 AM).

- Application to Napping Time: Since the Supreme Court had already established that the entire napping period constituted LSA working hours, it followed that Company Y was obligated under LSA Articles 13 and 37 to pay the statutory overtime and night work premiums for any portions of this napping time that qualified as statutory overtime or fell within statutory night work hours. This obligation exists regardless of whether the employment contract specifically provided for such additional payments for inactive napping time beyond the overnight allowance.

- Error in High Court's Approach: The High Court had recognized this statutory obligation but, according to the Supreme Court, had erred in its method of determining the amount of statutory overtime. This led to the remand.

This part of the judgment emphasizes that statutory labor protections, like minimum wage and overtime premiums, act as a floor. Contractual arrangements cannot undercut these mandatory provisions. Even if a contract specifies a certain payment (like an allowance) for a period, if that period is LSA working time, then all statutory requirements for wages and premiums related to that working time must still be met.

Reasons for Remand: Calculation Complexities

The Supreme Court remanded the case to the Tokyo High Court primarily due to errors in how the lower court calculated the statutory overtime hours and the base wage for premium payments.

- Variable Working Hours System (Henkei Rōdō Jikan Sei):

- The High Court had assumed that a variable working hours system (allowing flexible scheduling over a period like one month or four weeks, averaging out to meet weekly statutory limits) applied to the plaintiffs.

- The Supreme Court stated that for such a system to be validly implemented, the employer's work rules (or equivalent documents) must clearly specify the scheduled working hours for each day and each week within the defined variable period. A general statement about averaging hours (e.g., an average of 38 hours per week over a month) is insufficient.

- The High Court had not adequately determined whether Company Y's "monthly calendars," "building-specific calendars," and shift schedules properly met these requirements for specifying daily and weekly working hours.

- Furthermore, even if a variable system were correctly applied, the High Court's method of calculating overtime was flawed. A variable working hours system allows employers to schedule hours exceeding daily or weekly statutory maximums without it being considered overtime, but only up to the specifically scheduled hours for that day or week. Any work performed beyond those pre-determined scheduled hours still constitutes statutory overtime. It's not simply a matter of whether the average hours over the entire variable period remained within statutory limits.

- The Supreme Court instructed that, to correctly calculate statutory overtime, the High Court needed to first properly determine the scheduled working hours for the 24-hour shifts and for the weeks in which these shifts occurred, and then calculate any hours worked (including the napping time) that exceeded these specific scheduled hours.

- Base Wage for Premium Calculations:

- LSA Article 37 premiums (for overtime and night work) are calculated based on the employee's "normal wage" for regular working hours.

- This "normal wage" should be derived from the plaintiffs' "standard wage" (kijun chingin). However, LSA Enforcement Regulations (Article 21 at the time) specify certain types of allowances that must be excluded from this base wage calculation. These typically include family allowances, commutation allowances, and other payments not directly tied to the work performed.

- The plaintiffs' standard wage included a "living support allowance" (seikei teate), which varied based on household circumstances, and a "special allowance" (tokubetsu teate). The Supreme Court pointed out that if these allowances (or parts thereof) qualified as excludable allowances under the LSA regulations, they should have been removed from the base wage before calculating overtime premiums.

- The High Court had failed to investigate this and had instead used the employees' entire standard wage divided by scheduled working hours as the basis for "normal wage," which was deemed an error.

The remand was therefore necessary for the High Court to correctly apply the rules for variable working hours systems (if applicable) and to accurately determine the proper base wage for calculating the statutory overtime and night work premiums due to the plaintiffs for their napping time.

Broader Implications and Key Takeaways

The Supreme Court's decision in this case (often referred to by commentators as the "Taisei Building Management Case," though anonymized here as Company Y) offers several enduring principles relevant to the interpretation of working hours and wage obligations in Japan:

- The "Direction and Command" Test is Paramount: The core determinant of whether any time, including standby or on-call periods, counts as LSA working hours is whether the employee is under the employer's direction and command. This is a substantive test based on the actual conditions and obligations.

- "Guarantee of Freedom from Labor" is Crucial for Rest: For a period to be considered a true rest period (and thus not working hours), employees must be genuinely and unequivocally free from the obligation to perform work or to be ready to work. If they are required to remain on premises, respond to calls, or monitor systems, that freedom is likely compromised.

- Practical Constraints Matter: While the Supreme Court in this judgment focused on the "guarantee of freedom," the underlying assessment involves looking at the practical realities of the employee's situation. Factors such as restrictions on movement, the requirement for immediate response, and the potential for work to arise, all contribute to whether an employee is truly "free." The expectation that work arising should be "virtually nil" for it not to be working time sets a high threshold for employers.

- Distinction Between Contractual and Statutory Obligations: It is vital to differentiate between what an employment contract stipulates for wages and what the Labor Standards Act mandates.

- LSA working time does not automatically equate to a claim for contractually defined overtime rates if the contract has a different (but lawful) way of compensating that specific type of work (e.g., a fixed allowance for low-intensity standby).

- However, if a period is classified as LSA working time, then all statutory minimums, including overtime and night work premiums as per LSA Article 37, must be paid, regardless of potentially less generous contractual terms. The LSA provides a baseline of protection.

- Careful Calculation of Working Hours and Wages: Employers must be meticulous in how they define and apply working hour systems (especially variable ones) and how they calculate the base wage for statutory premium payments, ensuring all excludable allowances are correctly handled.

This judgment serves as a reminder that merely labeling a period as "napping time" or "rest" does not exempt it from being considered working hours if employees are not truly free from their work responsibilities and remain under the employer's effective control. The critical factor is the substantive nature of the employee's obligations and the degree of freedom afforded to them during such periods.