Supreme Court Clarifies Third‑Party Debtors in Japan’s Health Insurance (1973)

TL;DR (3‑sentence summary)

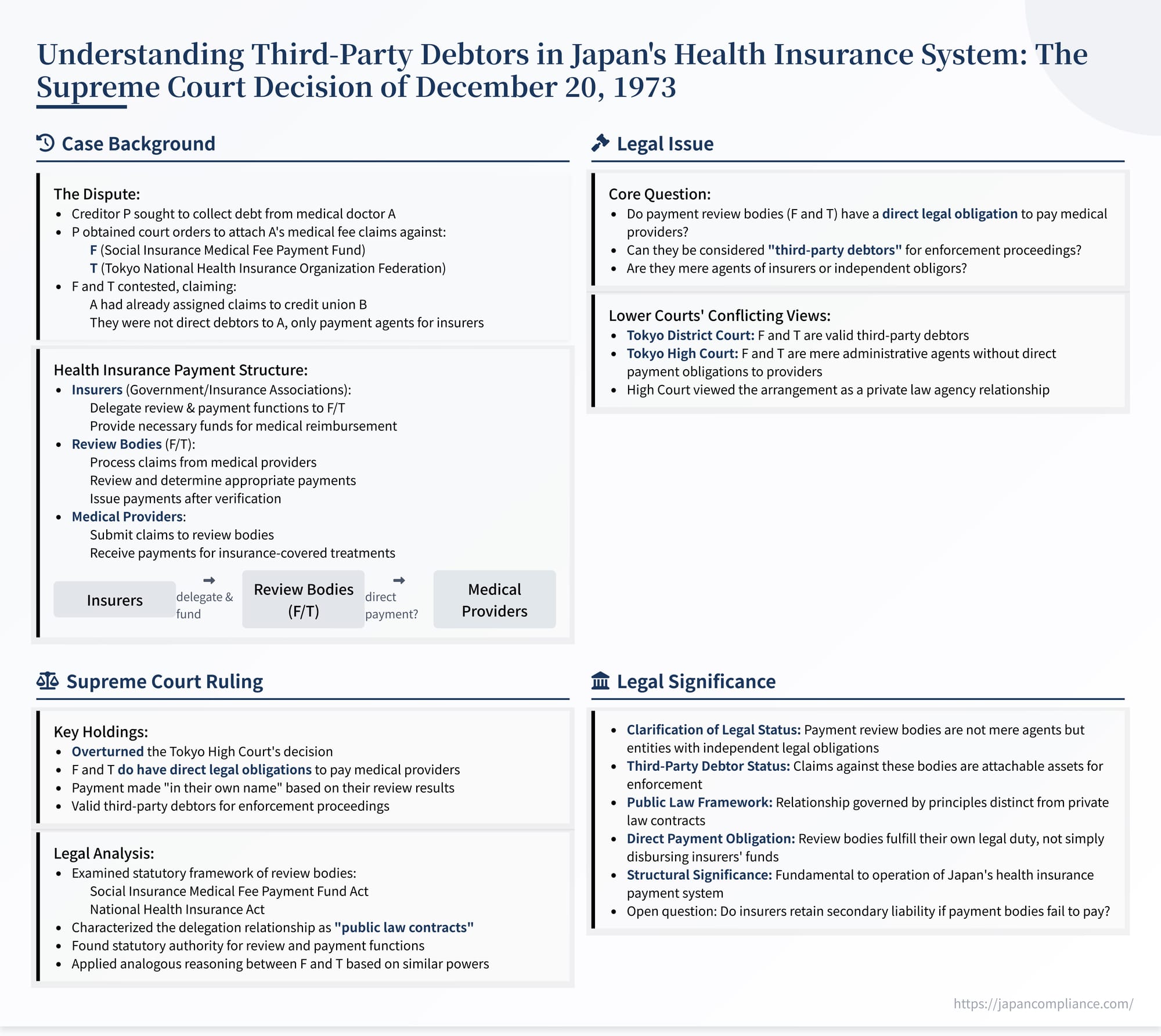

The 1973 Supreme Court of Japan held that the Social Insurance Medical Fee Payment Fund and National Health Insurance Federations become direct debtors—“in their own name”—once they are delegated to review and pay claims.

Because they owe a public‑law duty to pay providers, creditors of a doctor can garnish those payment bodies as third‑party debtors.

The decision overturned the Tokyo High Court and remains a cornerstone of Japan’s health‑insurance payment architecture.

Table of Contents

- Background: A Dispute Over Medical Fee Claims

- Lower Court Rulings: Conflicting Interpretations

- The Supreme Court’s Analysis: Public Law Contracts and Direct Obligations

- The Judgment: Reversal and Remand

- Legal Significance and Implications

On December 20, 1973, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in a case concerning a collection claim based on a collection order (1968 (O) No. 1311). This decision delved into the intricate legal relationships within Japan's health insurance system, specifically addressing whether the entities responsible for reviewing and paying medical fees on behalf of insurers hold a direct payment obligation to medical providers. The ruling clarified the legal status of these intermediary bodies, establishing them as legitimate third-party debtors against whom creditors could enforce claims owed by medical practitioners. This analysis explores the background, legal arguments, and the Supreme Court's reasoning in this pivotal case.

Background: A Dispute Over Medical Fee Claims

The case originated from a creditor-debtor relationship outside the immediate scope of the health insurance system. The plaintiff, P (whose litigation was later succeeded by others, including T), held a significant monetary claim against A, a medical doctor operating within Japan's insurance system. Seeking to recover the debt, P initiated legal proceedings in the Tokyo District Court.

Specifically, P sought to attach and collect debts owed to A by third parties. These third parties were two key organizations involved in processing medical fees under Japan's health insurance schemes:

- F (Social Insurance Medical Fee Payment Fund): P sought to seize A's claim against F for medical fees pertaining to May and June 1962, submitted under relevant social insurance laws. A court order for attachment and transfer (akin to garnishment and assignment for collection) regarding this claim was served on F on July 12, 1962.

- T (Tokyo Metropolitan National Health Insurance Organization Federation): P also targeted A's claim against T for medical fees pertaining to December 1960 and January 1961, submitted under the National Health Insurance system. A similar attachment and transfer order concerning this claim was served on T on February 14, 1961.

Armed with these court orders, P sued F and T directly to collect the specified amounts (after accounting for withholding tax, where applicable) plus damages for delay.

However, F and T contested P's claims. Their primary defense rested on the assertion that, prior to P's attachment and transfer orders, A had already assigned these future medical fee claims to another entity, B (a credit union). A had purportedly assigned the fees receivable from F for the period December 1961 to November 1962, notifying F on December 11, 1961. Similarly, A had allegedly assigned fees receivable from T for the period October 1960 to November 1961, notifying T in December 1960. F and T argued that these assignments of future claims were valid, meaning that at the time P obtained the court orders, the targeted debts (A's claims against F and T) no longer existed, rendering P's orders ineffective.

Crucially, F and T raised a more fundamental defense regarding their legal status. They argued they were not the actual debtors concerning the medical fees. Instead, they asserted that the insurers (the government or insurance associations under the relevant health insurance laws) were the true debtors obligated to pay the medical providers (like A). F and T contended they were merely acting as agents, entrusted by the insurers with the administrative tasks of reviewing claims and disbursing payments. Therefore, they argued, they could not be considered "third-party debtors" in the context of P's enforcement actions against A's assets.

Lower Court Rulings: Conflicting Interpretations

The lower courts arrived at opposite conclusions.

The Tokyo District Court (First Instance) ruled in favor of P, accepting that F and T could be subject to the attachment and transfer orders as third-party debtors holding funds owed to A. This initial judgment implicitly recognized a direct obligation, or at least a legal status sufficient for enforcement purposes, between the payment bodies (F and T) and the medical provider (A).

However, the Tokyo High Court (Second Instance) overturned the District Court's decision. The High Court sided with F and T on the fundamental issue of their legal status. It reasoned that F and T did not possess a direct, substantive legal obligation to pay medical fees to the providers like A. According to the High Court, the delegation of review and payment tasks from the insurers to F and T was merely an administrative arrangement for convenience. The High Court viewed the primary purpose of this delegation system as simplifying the process for providers, allowing them to submit claims to a single entity rather than numerous individual insurers, and streamlining the payment flow for insurers. It concluded that F and T's duty to pay was owed to the insurers as part of fulfilling their delegated tasks, not directly to the medical providers. Therefore, the High Court held, F and T were not the proper third-party debtors for A's medical fee claims, and P's collection action against them must fail. This ruling essentially characterized the payment delegation as a form of agency relationship under private law principles, where the agent (F/T) acts on behalf of the principal (insurer) without incurring direct liability to third parties (providers) based solely on that agency. P appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis: Public Law Contracts and Direct Obligations

The Supreme Court fundamentally disagreed with the High Court's interpretation and ultimately reversed its decision. The core of the Supreme Court's reasoning focused on the specific nature of the relationship created by the relevant health insurance laws when insurers delegate review and payment functions.

The Court examined the statutory framework governing F (Social Insurance Medical Fee Payment Fund) and T (National Health Insurance Organization Federation).

Regarding F (Social Insurance Medical Fee Payment Fund):

The Court noted that while the Health Insurance Act (Article 43-9, Paragraph 5, at the time) and the National Health Insurance Act (Article 45, Paragraph 5) simply stated that insurers could delegate review and payment functions to F, the Social Insurance Medical Fee Payment Fund Act (Fund Act) provided a more detailed picture of F's role and status.

According to the Fund Act:

- F is established as a juridical person specifically for the purpose of reviewing medical fee claims submitted by providers under various health insurance schemes and ensuring the prompt and proper payment of fees owed by insurers (including the government) to those providers (Articles 1, 2).

- F's main business operations involve receiving funds from insurers monthly and, after reviewing the submitted claims, paying the medical fees to the providers (Article 13, Paragraphs 1 & 2).

- F is subject to various forms of supervision by the relevant Minister (Article 20 et seq.).

- Crucially, F possesses the statutory authority, under certain conditions, to temporarily withhold payment of medical fees (Article 14-4).

Based on these provisions, the Supreme Court concluded that the relationship established when an insurer delegates the payment of medical fees to F is a public law contract. This characterization is significant because it moves the analysis away from purely private law agency principles (like mandate or委任 - inin). Furthermore, the Court held that once F accepts this delegation under the public law contract, it assumes a direct legal obligation to pay the medical fees to the providers. This payment is made in F's own name, based on the results of its own review of the claim.

The High Court's view, which denied F's direct payment obligation, was deemed an erroneous interpretation and application of the Fund Act, and this error clearly affected the outcome of the judgment.

Regarding T (Tokyo Metropolitan National Health Insurance Organization Federation):

The Court then turned to T, which handles claims under the National Health Insurance system. It noted that, based on the undisputed facts presented in the lower courts, T is a juridical person established under the National Health Insurance Act (Articles 83, 84) with insurers as its members. Its purpose includes reviewing and paying claims for medical benefits submitted by treatment facilities. T establishes review committees (Article 87) and is authorized to undertake review and payment upon delegation from insurers (Article 45, Paragraph 5).

The Supreme Court determined that both the National Health Insurance Unions (which act as insurers) and the Federation (T) should be considered public corporations (公法人 - kōhōjin). Consequently, the delegation contracts concluded between insurers and T regarding review and payment, based on Article 45, Paragraph 5 of the National Health Insurance Act, are also public law contracts.

Critically, the Court observed that the powers held by T in this context are "entirely similar" (全く類似する - mattaku ruiji suru) to the powers held by F under Article 13 of the Fund Act. Therefore, the Court reasoned by analogy (類推適用 - ruisui tekiyō) that the provisions governing F's payment obligations under the Fund Act should apply to T as well. This meant that when T accepts the delegation of review and payment from an insurer, it, like F, assumes a direct legal obligation to pay the costs of medical benefits to the medical institutions.

The High Court, having reached the opposite conclusion by denying this direct obligation, had again violated the law in a manner that demonstrably affected its final judgment.

The Judgment: Reversal and Remand

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court found the appellant's (P's) arguments valid on these key points. The High Court's judgment, which denied the direct payment obligations of F and T towards the medical provider A, was based on a misinterpretation of the governing statutes and the nature of the delegation relationship.

Therefore, the Supreme Court issued the following judgment:

- The original judgment (of the Tokyo High Court) is overturned (破棄する - hakisuru).

- The case is remanded (差し戻す - sashimodosu) to the Tokyo High Court for further proceedings consistent with the Supreme Court's interpretation.

The Court did not need to rule on the other arguments (such as the validity of the prior assignment of future claims to B) because the finding regarding the legal status of F and T as direct debtors was sufficient to warrant overturning the High Court's decision. The remand would allow the High Court to re-evaluate the case, now accepting that F and T were indeed proper third-party debtors against whom P could potentially enforce the claim, and then consider the remaining defenses, such as the alleged prior assignment.

Legal Significance and Implications

This 1973 Supreme Court decision carries significant weight in understanding the operational mechanics and legal structure of Japan's health insurance payment system.

- Clarification of Legal Status: The primary importance lies in its definitive clarification that the Social Insurance Medical Fee Payment Fund (F) and the National Health Insurance Organization Federations (T) are not mere payment agents or conduits for insurers. When entrusted with review and payment functions, they acquire a direct, independent legal obligation under public law to pay medical providers.

- Third-Party Debtor Status: Consequently, these organizations are legitimate third-party debtors concerning the medical fees owed to providers. This means creditors of medical providers (like P in this case) can legally target the fee claims held by providers against these payment bodies through enforcement procedures like attachment and collection orders. This aligned the law with the prevailing practice in enforcement proceedings at the time, which had treated these bodies as third-party debtors, a practice the High Court decision had thrown into doubt.

- Public Law Contract Nature: The Court's characterization of the delegation relationship between insurers and the payment bodies as a "public law contract" is noteworthy. It signifies that the relationship is governed by principles distinct from standard private law contracts like agency or mandate. This framing acknowledges the statutory basis, public purpose (ensuring efficient and proper payment of medical fees under a national system), and specific powers (like F's ability to withhold payment) associated with these bodies, placing the arrangement within the domain of public administrative law rather than purely private contractual law. This distinction was crucial in refuting the High Court's interpretation based on private law agency principles.

- Direct Payment Obligation: The finding of a direct payment obligation "in their own name" means that F and T are not simply disbursing the insurer's money on the insurer's behalf; they are fulfilling their own legal duty established by statute and the public law delegation contract, using funds provided by insurers but potentially also backed by their own operational funds or reserves. This reinforces their status as distinct legal entities with their own obligations within the payment flow.

- Implications for Insurers' Obligations: While the judgment establishes the direct liability of the payment bodies, it raises a subsequent question: does the insurer remain liable to the provider if the payment body fails to pay, or is the insurer discharged upon delegating the function and providing the necessary funds? This specific case didn't definitively resolve that point, although later jurisprudence and academic discussion suggest the insurer likely retains a secondary or ultimate liability, given that the delegation system is primarily for administrative convenience. However, the 1973 ruling firmly established the payment body as the primary and direct obligor once delegation occurs.

In essence, the Supreme Court recognized that the specialized nature and statutory functions of F and T elevated them beyond the role of simple agents. Their legally mandated roles in reviewing claims according to established rules and making payments directly conferred upon them a distinct legal obligation towards the medical providers, making their debts to those providers attachable by the providers' creditors. This understanding remains fundamental to the operation of Japan's health insurance payment system.