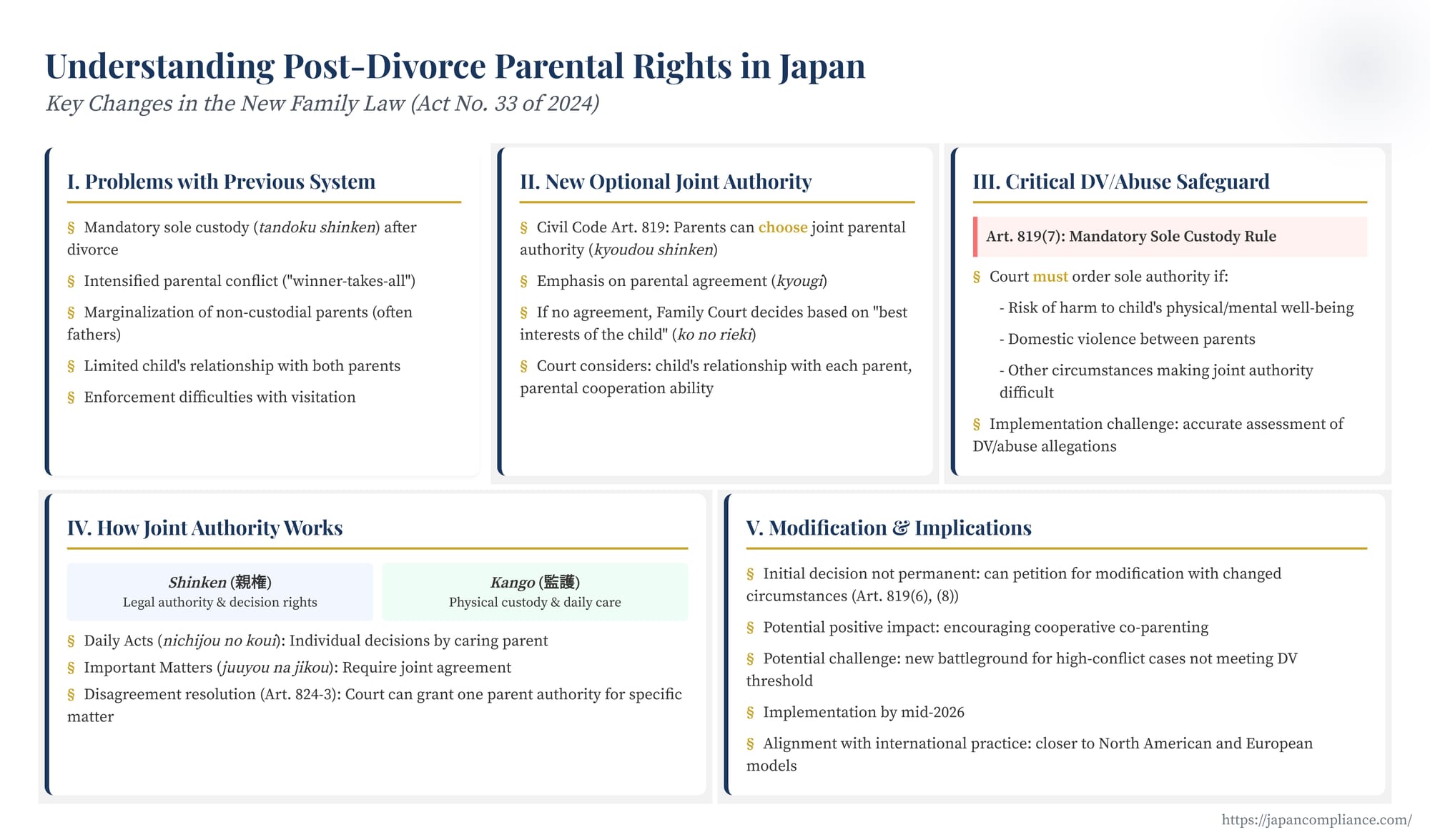

Understanding Post-Divorce Parental Rights in Japan: Key Changes in the New Family Law

TL;DR: Japan’s 2024 family-law reform lets divorcing parents choose joint parental authority, keeps a safety valve for domestic-violence cases, and clarifies how joint decision-making works. Courts will still rule case-by-case, but the shift moves Japan closer to global norms and forces employers, schools, and courts to update policies before full rollout in 2026.

Table of Contents

- Why the Change? Problems with Mandatory Sole Custody

- Introducing Optional Joint Parental Authority (Kyoudou Shinken)

- The Critical Safeguard: Mandatory Sole Authority in Cases of DV or Abuse

- How Joint Parental Authority Works in Practice

- Modification and Broader Implications

- Conclusion

Introduction

For decades following World War II, divorce in Japan automatically resulted in one parent being granted sole legal parental authority (shinken 親権) over minor children. This mandatory sole custody system, distinct from the joint custody arrangements prevalent in many Western nations, profoundly shaped post-divorce family dynamics. However, responding to evolving societal views, persistent challenges in ensuring child well-being after separation, and years of intense debate, Japan enacted a landmark reform of its family law in May 2024 (Act No. 33 of 2024, promulgated May 24, 2024).

A central pillar of this reform is the introduction of optional joint parental authority (kyoudou shinken 共同親権) after divorce. This represents a fundamental departure from the previous mandatory sole authority regime. While the law also includes significant changes related to child support and visitation, this article focuses specifically on explaining the new framework for determining and exercising parental authority after divorce in Japan. Understanding this shift is crucial for anyone seeking insight into the evolving legal landscape affecting families, employees, and the broader social fabric in Japan as it prepares for the law's full implementation (expected by mid-2026).

1. Why the Change? Problems with Mandatory Sole Custody

The decision to move away from mandatory sole shinken was driven by growing dissatisfaction with the perceived shortcomings of the old system:

- Intensified Parental Conflict: The "winner-takes-all" nature of mandatory sole custody often exacerbated conflict between divorcing parents, as the fight for shinken became a primary battleground.

- Marginalization of Non-Custodial Parents: The parent without shinken (most often the father under historical patterns) could feel legally and practically marginalized from their child's life, lacking formal decision-making rights and sometimes facing difficulties maintaining meaningful contact.

- Child's Relationship with Both Parents: Critics argued that automatically severing the legal parental authority of one parent did not always serve the child's best interest in maintaining stable and supportive relationships with both parents, provided both were fit and willing.

- Enforcement Difficulties: Disputes over visitation (oyako kouryuu) were common, sometimes fueled by the power imbalance created by the sole custody arrangement.

- Societal Shifts: Changing attitudes towards gender roles, increased emphasis on father involvement in child-rearing, and a desire to align more closely with international norms regarding shared parenting spurred calls for reform.

While proponents of the sole custody system emphasized its clarity and potential to shield children from ongoing parental conflict, the perceived downsides led to the consideration of alternative models, culminating in the adoption of optional joint shinken.

2. Introducing Optional Joint Parental Authority (Kyoudou Shinken)

The most significant change introduced by the 2024 reform is the ability for parents to share parental authority after divorce.

- The New Choice (Revised Civil Code Art. 819): Under the revised law, parents dissolving their marriage are no longer forced to choose only one parent to hold shinken. They now have the option to:

- Agree to maintain joint parental authority (kyoudou shinken).

- Agree to designate one parent to have sole parental authority (tandoku shinken).

- Have the Family Court (katei saibansho) decide between joint or sole authority if they cannot agree.

- Emphasis on Parental Agreement (Art. 819(1)): The law strongly encourages parents to determine the post-divorce parental authority arrangement through mutual consultation (kyougi), always prioritizing the child's best interests. If parents agree (whether on joint or sole authority), their agreement generally governs.

- Court Determination When Agreement Fails (Art. 819(2), (5)): If divorcing parents cannot reach an agreement on parental authority, or in cases of judicial divorce, the Family Court will make the determination. The court's decision must be based on the "best interests of the child" (ko no rieki).

- Factors for Court Decision (Art. 819(7)): When deciding between joint or sole authority, the court must consider various factors specified in the law, including:

- The child's relationship with each parent.

- The relationship between the parents themselves (their ability to cooperate).

- "All other circumstances" relevant to the child's welfare.

Crucially, the law does not establish a presumption in favor of either joint or sole authority. The decision is intended to be made on a case-by-case basis, centered on the specific child's needs and circumstances.

3. The Critical Safeguard: Mandatory Sole Authority in Cases of DV or Abuse (Art. 819(7))

Perhaps the most contentious aspect of the joint custody debate in Japan revolved around concerns for victims of domestic violence (DV) and child abuse. Opponents feared that joint custody could force victims into continued contact and co-decision-making with abusers, jeopardizing their safety and recovery. The final legislation incorporates a vital "safety valve" to address these concerns:

- Mandatory Sole Custody Rule: Article 819(7) explicitly mandates that the Family Court must order sole parental authority (not joint) if it finds either of the following conditions exist:

- Risk of Harm to Child: One parent's conduct poses a risk of harm to the child's physical or mental well-being (i.e., child abuse).

- Risk from Inter-Parental DV or Other Difficulties: Domestic violence between the parents creates a risk of harm, or other circumstances exist that make it difficult for the parents to jointly exercise parental authority in a way that serves the child's interests (e.g., extremely high conflict detrimental to the child).

- Significance: This provision acts as a critical safeguard, legally preventing the imposition of joint parental authority where abuse or severe conflict makes it inappropriate or dangerous. It reflects a legislative attempt to balance the potential benefits of shared parenting with the paramount need for child safety and victim protection.

- Implementation Challenge: The practical application of this safeguard will be crucial. Courts will face the challenge of accurately assessing allegations of DV or abuse, determining the level of "risk" or "difficulty" that precludes joint authority, and ensuring proceedings themselves do not further endanger victims. This will likely require specialized judicial training, sensitive fact-finding processes, and potentially input from DV experts or child psychologists.

4. How Joint Parental Authority Works in Practice

If joint parental authority is chosen or ordered, how does it function?

- Distinguishing Shinken (Parental Authority) and Kango (Custody/Care): It is vital to understand that joint shinken under Japanese law does not automatically mean joint physical custody or a 50/50 sharing of the child's time.

- Shinken encompasses the broad legal rights and responsibilities of parents, including making decisions about the child's upbringing, managing the child's property, giving consent for legal acts (like medical treatment or contracts), and representing the child legally.

- Kango refers to the actual day-to-day care, upbringing, and physical custody of the child.

Even if parents share shinken, they must still separately determine the child's primary residence and how day-to-day care responsibilities (kango) will be divided or assigned (this is typically done via agreement or court order under Revised Civil Code Art. 766). One parent might be designated the primary physical custodian (kangosha) while legal authority (shinken) remains joint.

- Exercising Joint Shinken (Revised Civil Code Art. 824-2): The law provides rules for how parents with joint authority make decisions:

- "Daily Acts" (Nichijou no Koui): Routine decisions related to everyday care and education (e.g., meals, clothing, homework help, minor recreational activities) can generally be made individually by the parent who has the child in their care at the time, without needing the other parent's explicit consent for each action.

- "Important Matters" (Juuyou na Jikou): Decisions likely to have a significant impact on the child's life require joint agreement. While not exhaustively listed, examples would likely include major medical decisions, choice of schools or religion, obtaining a passport, consenting to adoption, or significant changes to the child's residence.

- Unilateral Action in Limited Cases: One parent can act alone even on important matters if there is an urgent situation (kyuuhaku no jijou) requiring immediate action for the child's benefit, or if the other parent is incapable of acting (e.g., due to severe illness or unknown whereabouts).

- Resolving Disagreements under Joint Authority (Revised Civil Code Art. 824-3): Recognizing that disagreements are inevitable, the law provides a mechanism short of dissolving joint authority entirely. If parents with joint shinken cannot reach agreement on a specific important matter, either parent can petition the Family Court. The court, considering the child's best interests, can then issue an order granting one parent the authority to make the decision for that specific matter. This allows joint authority to continue for other aspects of the child's life.

5. Modification and Broader Implications

- Changing the Arrangement Later: The initial decision on sole or joint authority is not necessarily permanent. If circumstances change significantly after the divorce, either parent (or sometimes the child, depending on age and capacity) can petition the Family Court to modify the arrangement (e.g., from sole to joint, or joint to sole) if it is deemed necessary for the child's best interests (Revised Civil Code Art. 819(6), (8)).

- Potential Impacts:

- Co-Parenting: The introduction of optional joint custody may encourage more cooperative co-parenting relationships for some families, potentially benefiting children by maintaining stronger ties with both parents.

- Conflict: Conversely, for parents with high levels of conflict but who do not meet the threshold for the DV/abuse exception, joint decision-making requirements could become a new battleground, potentially exposing children to ongoing disputes.

- Need for Support: The success of joint custody arrangements often depends heavily on the parents' ability to communicate and cooperate. This highlights the critical need for accessible support services like mediation, co-parenting counseling, and parenting education programs.

- International Context: This reform brings Japan's approach to post-divorce parental authority closer to the models commonly found in North America and many European countries, where variations of joint legal and/or physical custody are the norm or a common option.

Conclusion

The introduction of optional joint parental authority (kyoudou shinken) marks a historic turning point in Japanese family law. By moving away from the rigid mandatory sole custody system, the 2024 reform offers divorced parents greater flexibility to tailor arrangements based on their specific circumstances and, ideally, the best interests of their children.

The framework emphasizes parental agreement but empowers the Family Court to intervene when necessary, guided by the child's welfare. The inclusion of strong safeguards mandating sole custody in cases involving domestic violence or abuse risk was a critical element in the legislative compromise and will be crucial in practice. The rules governing the exercise of joint authority attempt to balance shared responsibility with practical considerations for day-to-day life and provide mechanisms for resolving disagreements.

This fundamental shift away from mandatory sole custody holds the potential to reshape family dynamics and parent-child relationships after divorce in Japan. However, its success is not guaranteed by the legal changes alone. It will require a concerted effort to build robust support systems for families, provide clear guidance and adequate resources for the courts, and foster a societal understanding that prioritizes both child safety and, where appropriate and safe, the child's ongoing relationship with both parents. As Japan moves towards implementing these changes by mid-2026, the evolution of post-divorce parental rights will remain a key area of legal and social development.