Understanding Japan's Worker Dispatch Act: Compliance Risks and Best Practices for Foreign Companies

TL;DR

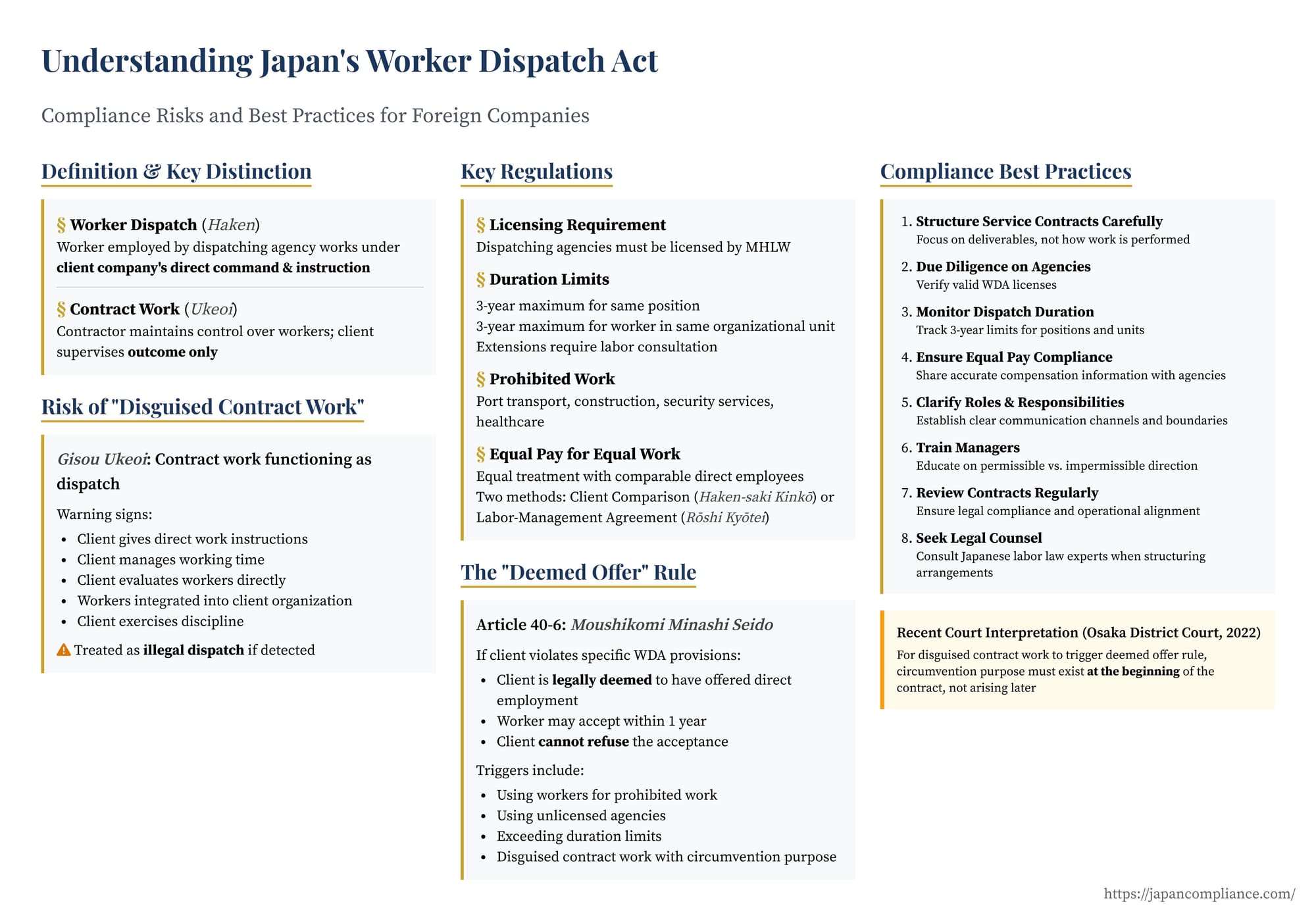

Japan’s Worker Dispatch Act imposes licensing, three-year tenure caps, equal-pay rules and a potent “deemed employment offer” sanction for illegal dispatch or disguised contracting. Foreign companies must structure outsourcing and temp-staff use carefully—tracking tenure, avoiding direct instruction, verifying agency licenses and aligning pay—to prevent automatic employee status and fines.

Table of Contents

- What Constitutes "Worker Dispatch" in Japan?

- The Risk of "Disguised Contract Work" (Gisou Ukeoi)

- Key Regulations and Restrictions under the WDA

- The "Deemed Offer of Employment" Rule (Article 40-6)

- The "Circumvention Purpose" in Disguised Contract Work

- Exemption for Public Entities (Article 40-7)

- Compliance Best Practices for Client Companies

- Conclusion: Navigating Flexibility with Diligence

Utilizing flexible staffing arrangements is a common global practice, allowing businesses to adapt to fluctuating demands and access specialized skills. In Japan, however, the use of non-permanent staff, particularly dispatched workers (often referred to as agency temps or contingent workers), is governed by a complex set of regulations under the Worker Dispatch Act (Act for Securing the Proper Operation of Worker Dispatching Undertakings and Improved Working Conditions for Dispatched Workers, commonly known as Roudousha Haken Hou). While offering flexibility, navigating the WDA presents significant compliance challenges and potential legal risks for companies utilizing these workers (referred to as "client companies").

Failure to comply can lead to severe consequences, including the unexpected creation of direct employment relationships. For foreign companies operating in Japan or considering using dispatched or contracted workers, a thorough understanding of the WDA's requirements, restrictions, and potential pitfalls is essential. This article provides a guide to the key aspects of the WDA, focusing on compliance risks such as "disguised contract work" (gisou ukeoi) and the critical "deemed offer of employment" rule, alongside best practices for mitigation.

What Constitutes "Worker Dispatch" in Japan?

Understanding the legal definition of worker dispatch is the first step towards compliance. The WDA defines worker dispatch as an arrangement where a worker, employed by one entity (the dispatching agency), engages in work for another entity (the client company) under the command and instruction (shiki meirei) of that client company, while maintaining their employment relationship with the dispatching agency.

This "command and instruction" element is the crucial differentiator between legitimate worker dispatch and other forms of outsourcing, such as a contract for work/services (ukeoi).

- Worker Dispatch (Haken): The client company directly instructs the dispatched worker on how to perform specific tasks, manages their day-to-day activities, and integrates them into their operational structure. The worker remains employed by the dispatch agency.

- Contract for Work/Services (Ukeoi): The client company contracts with a vendor (the contractor) for a specific outcome or service. The contractor, not the client, employs the workers performing the service and maintains direct command and instruction over them regarding how the work is done. The client's involvement is typically limited to defining the desired result and verifying its completion.

The Risk of "Disguised Contract Work" (Gisou Ukeoi)

A major compliance risk arises when an arrangement labeled as a contract for work (ukeoi) functions, in practice, like worker dispatch. This is known as "disguised contract work" (gisou ukeoi). This situation often occurs when a client company exerts direct command and instruction over workers who are formally employed by the service contractor.

Factors that regulators (like the Labor Bureaus) examine to determine if an arrangement constitutes gisou ukeoi include:

- Issuance of Direct Instructions: Does the client company give workers direct orders regarding tasks, procedures, or work methods?

- Management of Working Time: Does the client company directly manage the workers' start/end times, breaks, overtime, or leave requests?

- Performance Evaluation: Does the client company directly evaluate the workers' performance?

- Integration into Client's Organization: Are the workers treated similarly to the client's direct employees (e.g., using client email addresses, attending client-only meetings, being listed in client organizational charts)?

- Discipline: Does the client company have the authority to discipline the workers?

- Provision of Tools/Equipment: While not determinative alone, who provides essential tools and equipment can be a factor.

If an arrangement is found to be gisou ukeoi, it is treated as illegal worker dispatch, potentially triggering severe consequences under the WDA, most notably the "deemed offer of employment" rule.

Key Regulations and Restrictions under the WDA

Beyond the definition, the WDA imposes several critical restrictions and obligations:

- Licensing: Dispatching agencies must obtain a license from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). Client companies have a responsibility to ensure they are receiving workers only from properly licensed agencies. Receiving workers from an unlicensed agency constitutes illegal dispatch.

- Duration Limits: The WDA imposes time limits on the use of dispatched workers to prevent indefinite temporary staffing:

- Position-Based Limit: A client company generally cannot receive dispatched workers for the same position for more than three years. After three years, the client must directly hire someone for that role or cease using dispatched workers for it.

- Individual-Based Limit: A dispatched worker generally cannot work in the same organizational unit (e.g., department, section) of a client company for more than three years, even if their specific role changes within that unit.

- Exceptions: These limits do not apply to certain categories, such as workers dispatched by the agency under an indefinite-term employment contract, workers aged 60 or over, or certain fixed-term project work.

- Procedural Requirements: To extend dispatch beyond the initial limits (up to the three-year maximums), client companies generally need to solicit opinions from their labor union or a majority employee representative. Exceeding these limits without proper procedures constitutes illegal dispatch.

- Prohibited Work: Dispatch is prohibited for certain types of work, including port transport, construction, security services, and certain healthcare-related tasks (though exceptions exist for specific scenarios like temporary replacements or postpartum support). Using dispatched workers for these jobs is illegal.

- Equal Pay for Equal Work: A significant reform effective from April 2020 (for large companies) and April 2021 (for SMEs) mandates equal pay for equal work (dōitsu rōdō dōitsu chingin) principles for dispatched workers. Client companies must provide information about the treatment of their comparable direct employees to the dispatch agency. The dispatch agency is then obligated to ensure the dispatched worker's treatment (including base pay, bonuses, allowances, benefits, and education/training) is not unreasonable compared to the client's comparable employees. There are two main methods for achieving this:

- Client Comparison Method (Haken-saki Kinkō Kōsei Hōshiki): Treatment is balanced against comparable regular employees of the client company.

- Labor-Management Agreement Method (Rōshi Kyōtei Hōshiki): Treatment is determined based on a robust labor-management agreement concluded between the dispatch agency and its employee representative, provided the agreement ensures treatment equal to or better than the regional/occupational average and covers all key aspects of compensation and benefits. This method is commonly used but requires the agreement to meet strict standards. Failure by the dispatch agency (and indirectly, the client through information provision duties) to ensure equal treatment can lead to disputes and administrative guidance.

- Client Company Obligations: Client companies have various direct responsibilities, including managing working hours under Japanese labor law, ensuring workplace safety and health standards are met for dispatched workers, handling certain aspects of harassment complaints, and providing necessary facilities and information to enable dispatched workers to perform their duties.

The "Deemed Offer of Employment" Rule (Article 40-6)

Perhaps the most significant risk associated with non-compliance with the WDA is the "Deemed Offer of Employment" rule (moushikomi minashi seido) stipulated in Article 40-6.

- What it Means: If a client company receives dispatched workers in violation of certain provisions of the WDA or other labor laws, the client company is legally deemed to have offered a direct employment contract to the dispatched worker(s) under the same working conditions (salary, duties, work location, hours) that applied under the dispatch arrangement.

- Worker Acceptance: The dispatched worker can accept this deemed offer, creating a direct employment relationship between the worker and the client company, typically within one year of becoming aware of the violation. The client company generally cannot refuse this acceptance.

- Triggers for the Rule: The deemed offer is triggered by specific violations, including:

- Receiving dispatched workers for prohibited types of work (Art. 40-6(1)(i)).

- Receiving dispatched workers from an unlicensed agency (Art. 40-6(1)(ii)).

- Receiving dispatched workers beyond the permitted duration limits (Art. 40-6(1)(iii)).

- Engaging in "disguised contract work" (gisou ukeoi) (Art. 40-6(1)(iv)). (Note: Some sources use Art. 40-6(1)(v) for this, the numbering difference might depend on WDA versions/amendments. The substance relates to using non-dispatch contracts to circumvent the law).

The "Circumvention Purpose" in Disguised Contract Work

The trigger related to disguised contract work (often cited under Art. 40-6(1)(iv) or (v)) requires that the client company received the worker under a contract other than a worker dispatch agreement (e.g., a service contract) for the purpose (mokuteki) of evading the application of the WDA or other relevant labor laws.

A crucial question arose regarding when this circumvention purpose must exist for the deemed offer rule to apply. Must the intent to disguise the relationship exist from the very beginning of the contract, or can the rule be triggered if the client company only realizes later that the arrangement constitutes illegal dispatch but continues it with the intent to avoid WDA obligations?

- Osaka District Court Ruling (June 30, 2022): In a case involving a driver working at a government facility under a service contract, the Osaka District Court addressed this timing issue. The court ruled that the intent to circumvent the WDA must exist at the time the contract (disguised as non-dispatch) is concluded and when the services under that contract begin. The court reasoned that the wording of the article ("receiving services... under a contract concluded... for the purpose of evading...") points to the intent needing to be present at the outset. It also considered the severe consequences of the deemed offer rule and the practical difficulties in sometimes distinguishing dispatch command from service contract direction, arguing that applying the rule when the intent only arose later would be an overly broad interpretation.

- Divergence from Administrative Guidance? This ruling appeared to contradict existing administrative guidance (tsūtatsu), which had suggested that the deemed offer could be triggered even if the client company became aware that the arrangement was gisou ukeoi after the contract started and continued the arrangement with evasive intent at that later point.

- Implications: The Osaka court's interpretation, if upheld and followed, sets a higher bar for triggering the deemed offer rule in gisou ukeoi cases. It emphasizes the need to prove the client's evasive intent existed from the beginning of the contractual relationship. However, it's important to note this is a district court decision, and administrative bodies or higher courts might take a different view. Client companies should not rely on this ruling as a shield if they knowingly continue an arrangement that constitutes illegal dispatch. Proving intent, especially from the outset, remains complex.

Exemption for Public Entities (Article 40-7)

While less directly applicable to private foreign companies, understanding Article 40-7 provides context for the significance of Article 40-6. Article 40-7 exempts national and local government bodies from the automatic deemed offer of employment under Article 40-6.

Instead, if a public entity engages in illegal dispatch that would have triggered the deemed offer rule for a private company, the public entity is obligated to take "employment or other appropriate measures" (saiyou sonota no tekisetsu na sochi) concerning the worker, taking into account the purpose of Article 40-6.

The aforementioned Osaka District Court ruling (June 30, 2022) also interpreted this provision. The court held that Article 40-7 does not automatically obligate the public entity to directly hire the worker. The phrase "employment or other appropriate measures" is broad and allows the entity discretion based on various circumstances (including the specific nature of public employment). Appropriate measures could range from offering direct employment to providing information about other job vacancies or support for finding alternative employment. This highlights that the deemed offer rule in Article 40-6 is considered a particularly strong remedy, from which public entities are specifically exempted.

Compliance Best Practices for Client Companies

Given the complexities and potential liabilities, client companies utilizing dispatched or contracted workers in Japan should adopt proactive compliance strategies:

- Structure Service Contracts Carefully: When using service contracts (ukeoi), meticulously structure the agreement and operational reality to avoid any semblance of direct command and instruction over the contractor's employees. Ensure clear separation of responsibilities, focusing on deliverables rather than controlling the work process. Clearly define the scope of services and maintain distinct reporting lines.

- Due Diligence on Agencies: When using dispatched workers, verify that the dispatching agency holds a valid WDA license. Request and retain copies of their license.

- Monitor Dispatch Duration: Implement robust tracking systems to monitor the duration for which dispatched workers are assigned to specific positions and organizational units. Ensure compliance with the three-year limits and follow procedural requirements (opinion hearing) if extending assignments up to the limit.

- Ensure Equal Pay Compliance: Provide accurate and timely information to dispatch agencies regarding the treatment of comparable direct employees to facilitate compliance with equal pay for equal work rules. Understand whether the agency is using the client comparison method or the labor-management agreement method and seek assurances of compliance.

- Clarify Roles and Responsibilities: Maintain clear communication channels and delineate responsibilities between the client company and the dispatch agency/service contractor regarding worker management, safety, working hours, and other compliance matters.

- Train Managers: Educate internal managers and supervisors who interact with dispatched or contracted workers on the boundaries between acceptable direction within a service contract versus impermissible command/instruction that could create a gisou ukeoi situation. Emphasize that instructions on how to perform tasks should go through the contractor/agency supervisor, not directly to the worker.

- Review Contracts Regularly: Periodically review service contracts and dispatch arrangements to ensure they accurately reflect the operational reality and remain compliant with the evolving WDA regulations and interpretations.

- Seek Legal Counsel: Given the complexity and potential high stakes (especially the deemed offer rule), consult with experienced Japanese labor law counsel when structuring staffing arrangements, drafting contracts, or facing potential compliance issues.

Conclusion: Navigating Flexibility with Diligence

The Worker Dispatch Act provides a framework for flexible staffing in Japan, but it demands careful navigation by client companies. The risks associated with non-compliance, particularly the potential for illegal dispatch determinations leading to the "deemed offer of employment" rule under Article 40-6, are substantial. Understanding the distinctions between dispatch and service contracts, adhering strictly to duration limits and equal pay principles, and meticulously avoiding actions that constitute direct command over non-dispatched workers are paramount. While recent court interpretations, such as the Osaka District Court's ruling on the timing of "circumvention purpose," offer some clarification, the regulatory landscape requires ongoing vigilance. By implementing robust compliance practices, conducting thorough due diligence, and seeking expert legal advice, foreign companies can leverage flexible staffing options in Japan while mitigating the significant legal and financial risks associated with the Worker Dispatch Act.

- Worker Dispatch vs. Disguised Contracts in Japan: Avoiding Legal Pitfalls under Article 40-6

- Multi-Layered Disguised Contracting in Japan: Risks under the Worker Dispatching Act for U.S. Companies

- Workforce Management in Japan: Tackling Indirect Discrimination and the New Freelance Act

- Act on Securing the Proper Operation of Worker Dispatching Undertakings (Full English Translation)