Japan’s New Freelance Protection Act: Compliance Guide for US Companies

TL;DR

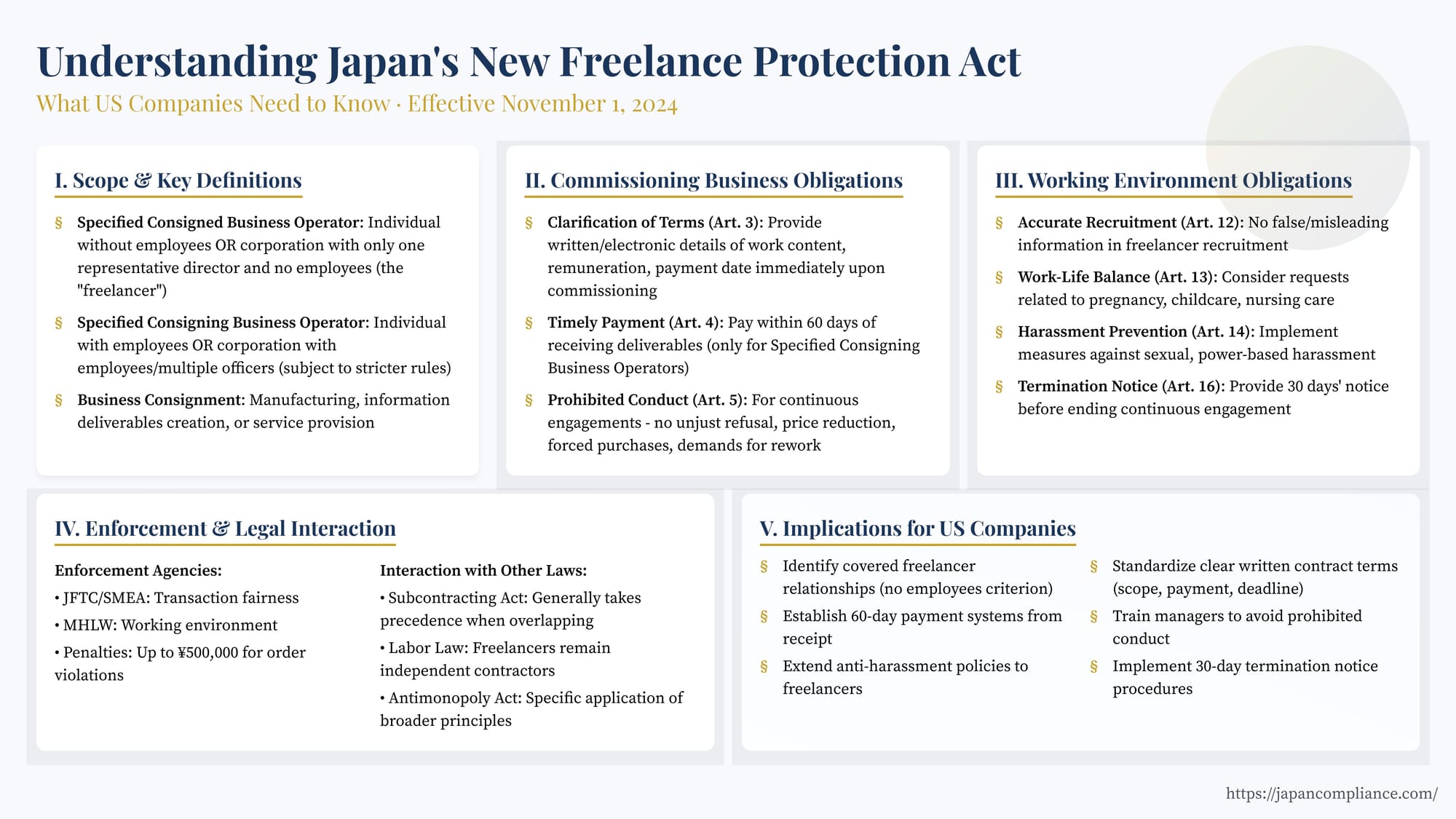

- Japan’s Freelance Protection Act (“FPA”) takes effect 1 Nov 2024, covering all B2B freelance engagements and imposing stricter rules for larger clients.

- Key duties: upfront written terms, 60-day payment cap, bans on abusive revisions, 30-day notice for long engagements, and anti-harassment obligations.

- Enforcement is split: JFTC/SMEA for transaction fairness; MHLW for working-environment duties. Fines up to ¥500k and public orders apply.

- US companies must audit freelancer contracts, payment cycles and policies to meet the new standards before Q4 2024.

Table of Contents

- Scope and Key Definitions (Article 2)

- Obligations on Commissioning Businesses

- Enforcement and Relationship with Other Laws

- Implications for US Companies Engaging Japanese Freelancers

- Conclusion

Japan, like many developed economies, has witnessed a significant surge in freelance work. Driven by digitalization, demographic shifts, and changing attitudes towards traditional employment, increasing numbers of individuals are choosing project-based or independent work arrangements. Estimates suggest millions operate as freelancers in Japan, contributing substantially to the economy. However, this rise has also highlighted the vulnerabilities freelancers often face: disparities in bargaining power with client businesses, ambiguity in contract terms, late or reduced payments, and a lack of the legal protections afforded to traditional employees.

In response to these challenges and following extensive surveys and discussions, the Japanese Diet enacted the "Act on Optimization of Transactions Related to Specified Consigned Businesses, etc." (特定受託事業者に係る取引の適正化等に関する法律 - Tokutei Jutaku Jigyōsha ni kakaru Torihiki no Tekiseika tō ni kansuru Hōritsu) in April 2023. Commonly referred to as the Freelance Protection Act (フリーランス保護新法 - Furīransu Hogo Shinpō), this landmark legislation is set to take effect on November 1, 2024. Its stated purpose is twofold: to ensure the fairness of transactions between businesses and freelancers, and to establish a stable working environment for these independent professionals.

For US companies engaging or planning to engage freelancers in Japan, understanding the scope, requirements, and implications of this Act is crucial for compliance and maintaining smooth operations. This article provides a comprehensive overview.

Scope and Key Definitions (Article 2)

The Act applies broadly to "business consignment" (業務委託 - gyōmu itaku) across various industries, where a business commissions work from specific types of freelancers. It does not apply to freelancer-to-consumer transactions or simple sales contracts. Understanding the definitions is key to determining applicability:

- Specified Consigned Business Operator (特定受託事業者 - Tokutei Jutaku Jigyōsha): This is the core definition of the "freelancer" protected by the Act. It refers to a business operator who is commissioned for work and:

- Is an individual who does not employ others (the term "employee" generally implies a relatively continuous employment relationship, excluding very short-term or temporary hires); OR

- Is a corporation with only one representative director (or equivalent officer) and no employees. This includes so-called "one-person companies."

- Specified Consigned Business Worker (特定受託業務従事者 - Tokutei Jutaku Gyōmu Jūjisha): This refers to the individual performing the work – either the individual freelancer or the sole representative director of the freelance corporation. This distinction is relevant for provisions concerning the working environment, such as harassment prevention.

- Consigning Business Operator (業務委託事業者 - Gyōmu Itaku Jigyōsha): This is any business operator (individual or corporation, regardless of size or employee count) that commissions work from a Specified Consigned Business Operator. All such businesses are subject to certain basic obligations, primarily regarding the clarification of transaction terms (Article 3).

- Specified Consigning Business Operator (特定業務委託事業者 - Tokutei Gyōmu Itaku Jigyōsha): This is a subset of Consigning Business Operators subject to stricter regulations (e.g., payment deadlines, prohibited conduct). This category includes:

- An individual business operator who employs others; OR

- A corporation that employs others OR has two or more officers (directors, statutory auditors, etc.).

The rationale is that these larger or more structured entities typically have significantly greater bargaining power over freelancers.

- Business Consignment (業務委託 - Gyōmu Itaku): Defined as a business commissioning another business operator to:

- Manufacture goods (including processing).

- Create "information deliverables" (情報成果物 - jōhō seikabutsu), such as software, content, designs, reports.

- Provide services (役務 - ekimu). This explicitly includes commissioning services for the commissioning business's own use (e.g., consulting, cleaning services for the client's office), a scope potentially broader than some interpretations under other laws like the Subcontracting Act.

Obligations on Commissioning Businesses

The Act imposes several key obligations on businesses that commission work from freelancers. Some apply to all commissioning businesses, while others apply only to the larger "Specified Consigning Business Operators."

1. Clarification of Transaction Terms (Article 3) - Applies to ALL Consigning Business Operators

To prevent disputes arising from ambiguity, all businesses commissioning work from a Specified Consigned Business Operator must clearly state the transaction terms immediately upon commissioning the work.

- Method: This clarification must be provided either in writing or via electronic means (e.g., email, messaging system on a platform, electronic documents). Notably, unlike the Subcontracting Act, prior consent from the freelancer is not required to use electronic means. However, if the freelancer requests a physical written document after receiving electronic terms, the commissioning business must provide it without delay.

- Required Content: The minimum required information includes:

- The specific content of the deliverables or services requested.

- The amount of remuneration.

- The payment due date.

- Other matters to be specified by Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) rules (likely to include details like inspection periods, intellectual property rights handling, etc.).

- Timing ("Immediately"): This implies providing the terms without delay upon making the commission.

- Exception: If certain details, like the final remuneration amount, cannot be fixed at the time of commissioning for a justifiable reason (e.g., based on project outcomes), those specific details must be clarified immediately once they are determined. The initial notification must still state how the final amount will be calculated.

2. Timely Payment of Remuneration (Article 4) - Applies to SPECIFIED Consigning Business Operators

Ensuring prompt payment is a core protection. Specified Consigning Business Operators must adhere to strict payment deadlines.

- Setting the Due Date: The payment due date must be set within 60 days from the date the commissioning business receives the deliverables or services. This calculation starts from the date of receipt, regardless of whether an inspection period is involved. The law encourages setting the shortest possible payment term within this 60-day limit.

- Default Due Date: If the parties fail to set a specific due date, or if they set a date exceeding 60 days from receipt, the due date legally defaults to the 60th day after receipt. This prevents commissioning businesses from unilaterally imposing excessively long payment terms.

- Payment Obligation: The commissioning business must pay the agreed remuneration by the established (or legally defaulted) due date. The only excuse for non-payment by the deadline is if the failure to meet obligations is directly attributable to the freelancer (e.g., incorrect bank details provided despite requests for correction). Inspection delays by the client do not justify late payment.

- Exception for Subcontracting Chains: A nuanced exception exists for multi-tiered subcontracting. If a Specified Consigning Business Operator (acting as an intermediary subcontractor) re-consigns work received from its own client (the prime contractor) to a freelancer (the Specified Consigned Business Operator), the payment deadline to the freelancer can potentially be set within 30 days from the date the intermediary is scheduled to be paid by the prime contractor (the "prime payment due date"). However, this exception applies only if specific conditions are met, including clearly notifying the freelancer of this arrangement and the prime payment due date when clarifying terms under Article 3. This aims to balance the cash flow realities of intermediary businesses with freelancer protection but requires careful handling and transparency.

- Consideration for Advance Payments (Article 4, Paragraph 6): If the commissioning business receives an advance payment from its client for the project, it should consider (though not strictly mandated) paying the freelancer necessary start-up costs as an advance payment, upon request.

3. Prohibited Conduct (Article 5) - Applies to SPECIFIED Consigning Business Operators in CONTINUOUS Engagements

To prevent abuse of potentially superior bargaining power, Article 5 lists specific unfair practices that Specified Consigning Business Operators are prohibited from engaging in. Crucially, these prohibitions apply only when the business consignment is "continuous" – meaning it lasts for a period longer than a threshold to be set by Cabinet Order (likely 1 month or 6 months, based on governmental materials and discussions; renewable contracts exceeding the threshold are also covered). This limitation aims to target situations where economic dependency might make freelancers more vulnerable, while avoiding undue burden on businesses for very short-term, one-off projects.

The prohibited conducts largely mirror those found in Japan's Subcontracting Act (Shitauke-hō):

- Refusal to Receive: Refusing to accept the deliverables or services provided by the freelancer without reasons attributable to the freelancer.

- Reduction of Remuneration: Reducing the agreed-upon remuneration without reasons attributable to the freelancer.

- Returning Goods: Returning delivered goods/work product after acceptance without reasons attributable to the freelancer.

- Unreasonable Price Reduction ("Buying-叩き" - Kaitataki): Unjustly setting remuneration significantly lower than the normal market rate for similar work at the time of commissioning.

- Forced Purchase/Use: Coercing the freelancer to purchase goods or use services designated by the commissioning business without a justifiable reason (e.g., necessary for quality uniformity).

- Requesting Unjust Economic Benefits: Demanding the provision of money, services, or other economic benefits from the freelancer that unjustly harm their interests (e.g., demanding unreasonable discounts or contributions unrelated to the commissioned work).

- Unjust Changes or Re-dos: Unjustly demanding changes to the content of the work or requiring the work to be redone after acceptance, without reasons attributable to the freelancer, in a way that harms the freelancer's interests (effectively forcing unpaid extra work).

Obligations Regarding the Working Environment

Beyond transaction fairness, the Act introduces provisions aimed at improving the broader working environment for freelancers, primarily imposing duties on Specified Consigning Business Operators.

1. Accurate Information in Recruitment Advertisements (Article 12)

When advertising to recruit freelancers (via publications, websites, etc.), Specified Consigning Business Operators must not provide false information or information likely to mislead potential applicants regarding the nature of the work, remuneration, or other working conditions specified by ordinance. Furthermore, the information provided must be accurate and kept up-to-date.

2. Consideration for Balancing Work with Personal Life (Article 13)

Recognizing the challenges freelancers face in balancing work with personal responsibilities, the Act mandates consideration, particularly for longer engagements:

- Duty in Continuous Engagements: For continuous engagements (exceeding the threshold set for Article 5), Specified Consigning Business Operators must, upon request from the freelancer, give necessary consideration to allow them to balance the commissioned work with needs related to pregnancy, childbirth, childcare, or nursing care.

- Effort Duty in Shorter Engagements: For engagements shorter than the continuous threshold, Specified Consigning Business Operators must endeavor to provide such consideration upon request.

- Scope of "Consideration": This does not mean the commissioning business must grant every request. It requires them to seriously consider the freelancer's request and make reasonable efforts to accommodate it where feasible (e.g., adjusting deadlines if possible, permitting remote work methods). Specific examples and guidance are expected from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW).

3. Harassment Prevention Measures (Article 14)

Specified Consigning Business Operators have a duty to take necessary measures to ensure that the working environment for the Specified Consigned Business Worker (the individual) is not harmed by harassment.

- Covered Harassment: This includes sexual harassment, "power harassment" (abuse of superior position, pawahara), and harassment related to pregnancy, childbirth, childcare, etc. (matahara).

- Required Measures: Businesses must implement measures such as establishing clear anti-harassment policies, conducting training for their own employees who interact with freelancers, setting up consultation channels for freelancers, and ensuring prompt and appropriate responses if harassment occurs. Utilizing existing internal systems developed for employees is permissible.

- Prohibition of Retaliation: It is illegal to treat a freelancer disadvantageously (e.g., terminate their contract, reduce their pay) because they reported harassment.

4. Advance Notice of Termination or Non-Renewal (Article 16) - Applies to Continuous Engagements

To provide freelancers with a degree of stability in ongoing relationships, Specified Consigning Business Operators must follow specific procedures when ending a continuous engagement (one exceeding the Article 5 threshold):

- Advance Notice: At least 30 days' advance notice must be given before terminating the contract mid-term or deciding not to renew it upon its expiration date.

- Disclosure of Reasons: If the freelancer requests the reason for termination or non-renewal during the notice period, the commissioning business must disclose it without delay.

- Exceptions: MHLW ordinances will define exceptions to these requirements, likely including cases of emergency (e.g., natural disasters) or situations where termination is due to the freelancer's own serious breach or fault.

Enforcement and Relationship with Other Laws

The Act establishes enforcement mechanisms involving multiple government agencies:

- Transaction Fairness (Arts. 3-5): Enforced primarily by the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) and the Small and Medium Enterprise Agency (SMEA). They can request reports, conduct inspections, issue guidance and advice, make recommendations for corrective measures, and issue cease-and-desist orders (with public disclosure) if recommendations are ignored. The SMEA Director-General can also request the JFTC to take action.

- Working Environment (Arts. 12-16): Enforced by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). Similar powers exist for guidance, advice, recommendations, and orders (including public disclosure for non-compliance with harassment prevention or termination notice rules).

- Penalties: Failure to comply with orders or obstruction of investigations can result in fines of up to ¥500,000. Corporations can face double liability (fines for both the company and the responsible individual).

- Freelancer Reporting: Freelancers can report suspected violations directly to the appropriate agency (JFTC/SMEA for transaction issues, MHLW for working environment issues). The Act explicitly prohibits retaliation against freelancers for making such reports (Articles 6 and 17).

It's important to understand how the Freelance Protection Act interacts with existing laws:

- Subcontracting Act (Shitauke-hō): This law protects small subcontractors from unfair practices by larger parent companies (defined by capital thresholds). The Freelance Act fills gaps by applying to commissioning businesses that don't meet the Subcontracting Act's capital requirements and covers a broader range of service transactions. Where obligations overlap (e.g., payment terms, prohibited conduct), the Subcontracting Act, which often has stricter requirements (like mandatory interest on late payments), generally takes precedence. However, the Freelance Act uniquely covers working environment aspects like harassment and childcare consideration.

- Antimonopoly Act (Dokkin-hō): The Freelance Act's prohibitions on unfair conduct (Article 5) are specific applications of the broader principle against Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position under the Antimonopoly Act. The Freelance Act provides clearer, more specific rules tailored to the freelancer context, potentially making enforcement easier for common grievances than relying solely on the general Antimonopoly Act provisions.

- Labor Law (Rōdō-hō): The Freelance Protection Act does not automatically grant freelancers the status of "workers" (労働者 - rōdōsha) under Japanese labor law (like the Labor Standards Act or Labor Union Act). They remain, by default, independent business operators without rights to paid leave, overtime pay, minimum wage protections derived from labor law, or dismissal protections applicable to employees. The determination of whether a specific individual factually qualifies as a "worker" under labor law remains a separate analysis based on established criteria (degree of control, economic dependency, etc.). However, the working environment provisions (harassment, childcare consideration) clearly borrow concepts and impose obligations analogous to those found in labor law protections for employees.

Implications for US Companies Engaging Japanese Freelancers

US companies utilizing freelance talent in Japan need to take several steps to ensure compliance with the new Act:

- Identify Covered Relationships: Assess whether individuals or single-person corporations engaged in Japan meet the definition of "Specified Consigned Business Operator." Remember the "no employees" criterion is key.

- Standardize Contract Clarity: Implement procedures to ensure that essential terms (scope of work, deliverables, remuneration, payment due date) are always provided clearly in writing or electronically at the start of any engagement with covered freelancers. Review standard contract templates.

- Verify Payment Timelines: If your company (or its Japanese subsidiary/branch) meets the definition of a "Specified Consigning Business Operator" (employs staff in Japan or has multiple officers), ensure payment systems are set up to pay freelancers within 60 days of receiving their work. Document receipt dates carefully. Understand the nuances if operating within a subcontracting chain.

- Review Policies for Continuous Engagements: If engaging freelancers for periods exceeding the forthcoming Cabinet Order threshold (e.g., 6+ months), review internal guidelines and train managers to avoid the prohibited conducts listed in Article 5 (unfair pay cuts, forced purchases, abrupt changes, etc.).

- Adapt Working Environment Protocols: Extend or adapt existing anti-harassment policies, training, and reporting channels to cover freelance workers interacting with your employees. Establish a process for receiving and genuinely considering freelancer requests related to balancing work with childcare or nursing care responsibilities.

- Implement Termination/Non-Renewal Procedures: For continuous engagements, establish a clear process for providing the required 30-day advance notice and for responding to requests for reasons for termination or non-renewal.

- Vendor/Platform Management: If using platforms to engage freelancers, understand how the platform facilitates compliance with the Act's requirements (e.g., term provision, payment processing). The ultimate responsibility likely remains with the commissioning business.

- Internal Training: Ensure relevant personnel (procurement, HR, legal, project managers) are aware of the Act's requirements.

Conclusion

The Freelance Protection Act marks a significant development in Japanese law, acknowledging the growing importance of the freelance sector and addressing long-standing concerns about fair treatment and working conditions. While it stops short of granting employee status, it imposes substantial new obligations on businesses, particularly larger ones, regarding transaction transparency, payment promptness, prevention of unfair practices, and consideration for the freelancer's working environment and personal circumstances. US companies operating in Japan must familiarize themselves with these new rules, adapt their contracting and operational practices accordingly, and foster a compliant and respectful relationship with their Japanese freelance partners. As the effective date of November 1, 2024, approaches, proactive preparation will be key to navigating this new legal landscape successfully.

- Employee or Contractor? How Japanese Courts Classify Entertainers Under Labor Law

- Setting the Stage for Respect: Addressing Harassment in Japan’s Entertainment Industry

- Post-Pandemic Japanese Labor Law: Dismissal, Relocation & Side-Job Pitfalls Explained

- JFTC & SMEA – Freelance Protection Act Q&A (Japanese)

- MHLW – Harassment Prevention Guidelines for Freelancers (Japanese)