Post-Pandemic Japanese Labor Law: Dismissal, Relocation, Side-Jobs & Fixed-Term Pitfalls Explained

TL;DR

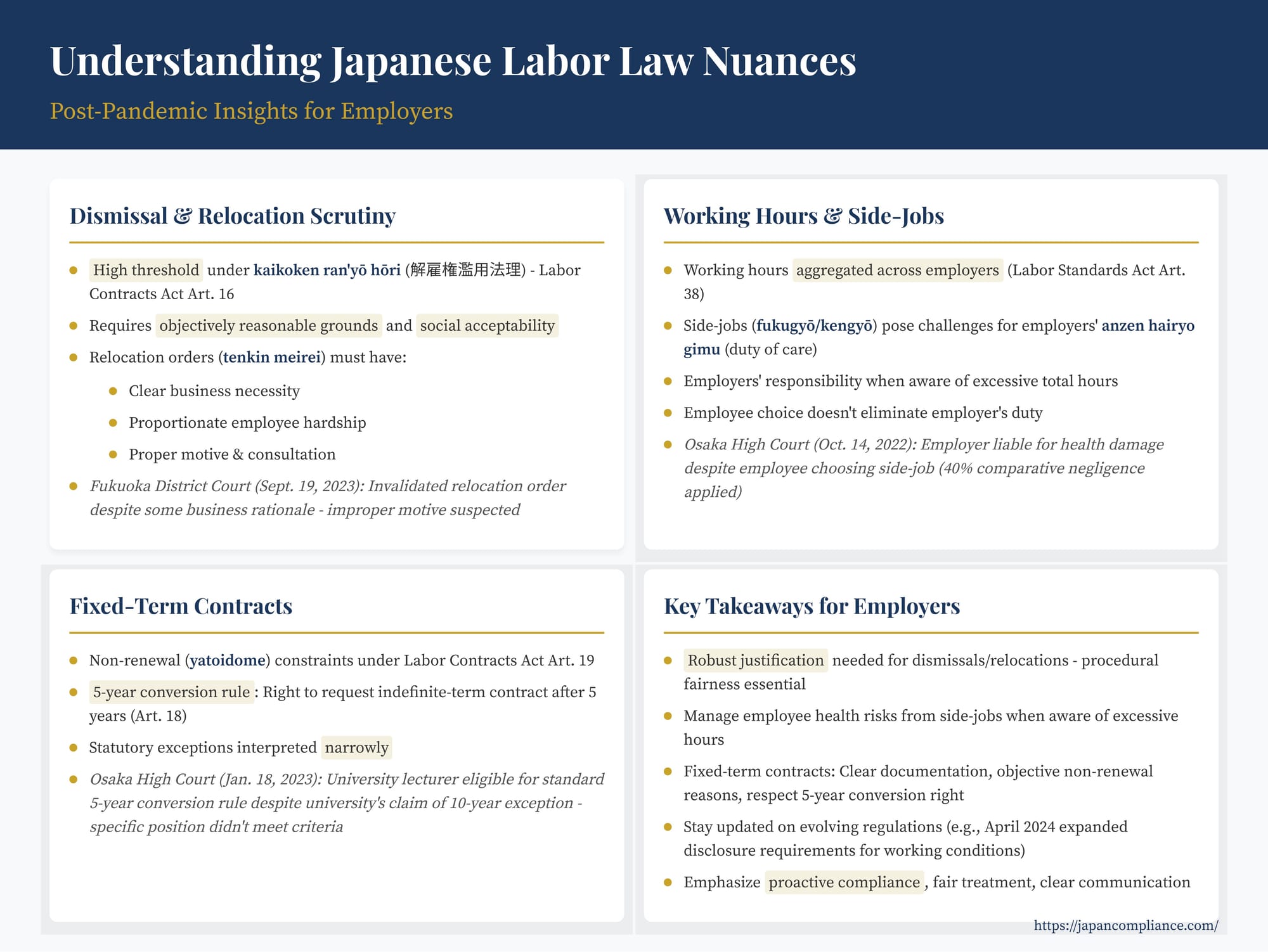

- Japanese courts kept a high bar for dismissal and struck down a retaliatory long-distance transfer in 2023.

- Employers are liable for overwork injuries even when total hours stem from side-jobs they know (or should know) about.

- Non-renewal of fixed-term staff and refusal to grant indefinite conversion face strict scrutiny—sector exemptions apply narrowly.

- Key action points: justify dismissal/relocation with hard evidence, track total hours across side-jobs, and audit fixed-term contracts before the 5-year mark.

Table of Contents

- The High Bar for Dismissal and Scrutiny of Relocation Orders

- Managing Working Hours: Side-Jobs and the Employer's Duty of Care

- Fixed-Term Contracts: Non-Renewal and Conversion Rights

- Key Takeaways for Employers in Japan

Japan's labor law landscape, while rooted in principles that historically favored long-term employment stability, is continuously evolving. Trends towards greater labor mobility, diverse working arrangements like side-jobs (副業・兼業, fukugyō/kengyō), and the impacts of events like the COVID-19 pandemic have brought specific legal nuances into sharper focus. For foreign companies operating in Japan, understanding these intricacies—particularly concerning termination, relocation, working hour management, and fixed-term contracts—is crucial for effective human resource management and legal compliance. Recent court decisions offer valuable insights into how Japanese courts approach these complex issues.

The High Bar for Dismissal and Scrutiny of Relocation Orders

Dismissing an employee in Japan is notoriously difficult compared to many Western jurisdictions. The doctrine of "abuse of dismissal right" (解雇権濫用法理, kaikoken ran'yō hōri), codified in Article 16 of the Labor Contracts Act (労働契約法, Rōdō Keiyaku Hō), requires dismissals to have objectively reasonable grounds and be considered socially acceptable. This sets a high threshold, demanding strong justification and procedural fairness.

Similarly, while employers generally have the right to relocate employees (転勤命令, tenkin meirei), this right is not absolute and is subject to the doctrine of abuse of rights. A relocation order can be deemed invalid if it lacks business necessity, imposes excessive hardship on the employee disproportionate to the business need, or is issued for an improper motive.

A case decided by the Fukuoka District Court, Kokura Branch on September 19, 2023, illustrates the scrutiny applied, especially in sensitive contexts. The case involved a high school teacher at a private educational institution whose initial dismissal was ruled invalid by a higher court. Despite this ruling, the institution did not allow the teacher to return to his original workplace (in Kitakyushu) and subsequently ordered his relocation to a distant school operated by the same institution (in Fukushima).

The court acknowledged some business necessity for the transfer (e.g., a staffing need at the destination school and reduced class hours at the original school). However, it invalidated the relocation order as an abuse of rights based on several factors:

- Improper Motive Strongly Suspected: The sequence of events—the contested dismissal, the refusal to allow the teacher back on the original premises even after the dismissal was invalidated, the lack of prior consultation about the transfer, and the unusual nature of such a long-distance transfer for regular teachers at the institution—led the court to strongly suspect an improper motive, essentially viewing the relocation as a way to sideline the employee following the failed dismissal attempt.

- Excessive Disadvantage to Employee: The court recognized that relocating the teacher from Kitakyushu, where he had lived and worked for over 20 years, to Fukushima constituted a disadvantage significantly exceeding what an employee should normally be expected to endure, particularly given the questionable motive and limited business necessity.

- Lack of Consultation: The absence of any meaningful consultation or consideration of the employee's circumstances before issuing the drastic relocation order further supported the finding of abuse.

This case serves as a reminder that even where some business logic exists, relocation orders, especially long-distance ones impacting long-serving employees or occurring in contentious circumstances (like post-litigation), will be closely examined. Employers must demonstrate clear business necessity, consider employee hardship, engage in consultation where appropriate, and ensure the order is not tainted by retaliatory or other improper motives.

Managing Working Hours: Side-Jobs and the Employer's Duty of Care

The rise of side-jobs (kengyō or fukugyō) presents challenges for managing working hours and ensuring employee well-being. While government guidelines now encourage companies to permit side-jobs in principle (revising older models that often prohibited them), legal responsibilities regarding working hours remain complex.

Article 38, Paragraph 1 of the Labor Standards Act (労働基準法, Rōdō Kijun Hō) stipulates that working hours are aggregated even if performed at different workplaces ("事業場を異にする場合," jigyōjō o koto ni suru baai). While interpretation exists, administrative guidance and prevailing views suggest this aggregation applies even when the employers are different (i.e., in cases of side-jobs). This means the combined hours worked for multiple employers count towards statutory limits on daily/weekly hours and overtime regulations.

The Osaka High Court decision on October 14, 2022, addressed an employer's responsibility in such a situation. An employee worked extensive hours, including overnight shifts, at a gas station operated under contract by Company 1 (Y1). He also worked day shifts at the same gas station under a separate contract with Company A, which operated the day shift. This resulted in extremely long consecutive work periods (over 150 days without a full day off) and total monthly hours far exceeding regulatory limits, ultimately leading to the employee developing a mental health condition.

Company 1 (Y1) argued it wasn't responsible for hours worked for Company A. However, the High Court found Company 1 liable for breaching its duty of care (anzen hairyo gimu). Key factors included:

- Awareness/Ease of Awareness: Since both jobs were at the same physical location, Company 1 was aware, or could easily have become aware, of the employee's dual employment and excessive total working hours. The court distinguished this from situations where an employee has an unrelated side-job unknown to the primary employer.

- Employer's Duty: Despite the employee choosing to take on the second job, the court affirmed the employer's fundamental duty to ensure working conditions do not harm the employee's health. Recognizing the hazardous working pattern, Company 1 had an obligation to take steps to mitigate the risk, such as adjusting the employee's shifts within its own control.

- Employee's Contribution (Contributory Negligence): The court acknowledged that the employee actively chose this demanding schedule. However, it stated that this active choice did not negate the employer's duty of care. Instead, the employee's contribution was considered under the principle of comparative negligence (過失相殺, kashitsu sōsai), leading to a 40% reduction in damages awarded, rather than absolving the employer entirely.

This ruling underscores that employers cannot ignore the health risks posed by excessive working hours, even if those hours are accumulated across multiple jobs, especially when the employer is aware or can reasonably ascertain the employee's overall work schedule. While direct intervention in employment with another company is generally not possible, employers aware of dangerous overwork situations have a duty to manage the work within their own control (e.g., adjusting shifts, ensuring rest periods) to mitigate health risks. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) guidelines on side-jobs also emphasize communication between employers and employees regarding total working hours and health management.

Fixed-Term Contracts: Non-Renewal and Conversion Rights

Fixed-term employment contracts are common in Japan, but their non-renewal (yatoidome) is subject to legal constraints, particularly after multiple renewals or when the employee has a reasonable expectation of renewal. Article 19 of the Labor Contracts Act effectively codifies the "abusive non-renewal doctrine," stating that a non-renewal may be invalidated if it lacks objectively reasonable grounds and is not socially acceptable, especially if the contract is functionally equivalent to an indefinite one or if renewal expectations are high.

Furthermore, Article 18 of the same Act grants employees the right to request conversion to an indefinite-term contract upon completing a fixed-term contract that brings their total continuous employment period with the same employer beyond five years.

However, exceptions exist. The Osaka High Court decision on January 18, 2023, dealt with the non-renewal of a fixed-term university lecturer and the applicability of the Act on the Term of University Teachers, etc. (大学教員等の任期に関する法律, Daigaku Kyōin Tō no Ninki ni Kansuru Hōritsu, often called 大学教員任期法, Daigaku Kyōin Ninki Hō). This law allows universities to set fixed terms for certain academic positions beyond the standard rules, and crucially, Article 7 extends the five-year threshold for indefinite contract conversion requests under Article 18 of the Labor Contracts Act to ten years for qualifying academic staff employed under these specific term-setting provisions.

In this case, the lecturer, initially hired non-tenure track, was later appointed as a fixed-term (3 years) sen'nin kōshi (専任講師, often translated as full-time lecturer/instructor), renewed once for another 3 years with a clause explicitly stating no further renewal. Before the second term ended (totaling 6 years as sen'nin kōshi, plus prior non-tenure time), the university notified him of non-renewal, citing the planned closure of his specific course/program due to declining enrollment. The lecturer argued he had the right to convert to an indefinite contract under Article 18 (as his total employment exceeded 5 years). The university countered that the 10-year exception under the University Teacher Term Law applied.

The Osaka High Court sided with the lecturer, reversing the lower court's decision. It held that the 10-year exception did not automatically apply just because the employee held the title of sen'nin kōshi. The court narrowly interpreted the requirements of Article 4 of the University Teacher Term Law (which defines the types of positions eligible for fixed terms eligible for the 10-year rule). It found that the university had not demonstrated that the lecturer's specific position met the criteria outlined in the law, such as being in a field where securing diverse talent is particularly necessary (Article 4(1)(i)) or being part of a fixed-term educational/research project (Article 4(1)(iii)).

The court reasoned that the lecturer was primarily hired to maintain a specific vocational training course (care worker certification) and his duties, while including some teaching in other departments later, were predominantly educational rather than research-focused. There was no evidence that his role required special measures to ensure personnel fluidity or involved a temporary project. The planned closure of his course was deemed a managerial decision, not grounds for applying the statutory exceptions for fixed-term appointments under the University Teacher Term Law.

Therefore, the standard 5-year rule under Article 18 of the Labor Contracts Act applied. Since the lecturer had worked continuously for over five years and requested conversion, the non-renewal was invalid, and he was deemed to hold an indefinite-term contract.

This case highlights that employers, especially in sectors with specific legislation like universities, cannot assume that statutory exceptions to general labor rules apply automatically based on job titles. The specific nature and purpose of the position must meet the legal requirements for such exceptions. For standard fixed-term contracts, employers must be prepared to provide objective, reasonable, and socially acceptable grounds for non-renewal, particularly after several renewals or long service, and must respect the employee's right to request conversion to an indefinite contract after five years of continuous service.

Key Takeaways for Employers in Japan

Navigating Japanese labor law requires careful attention to detail and an understanding of principles that often prioritize employee protection. Key takeaways from these recent developments include:

- Dismissal & Relocation Require Strong Justification: Terminating employees remains challenging. Relocation orders must be based on clear business needs, outweighing employee hardship, and free from improper motives, especially following disputes. Procedural fairness and consultation are important.

- Acknowledge and Manage Side-Job Impacts: Employers cannot ignore the health implications if they know or can reasonably know that an employee's total working hours (including side-jobs) are excessive. While direct control over other employment is limited, managing workload within one's own company and communicating with the employee about health risks are crucial aspects of the duty of care. Familiarize yourself with MHLW guidelines on managing side-jobs.

- Handle Fixed-Term Contracts Carefully: Non-renewal requires objective justification, particularly after multiple renewals. Be aware of the 5-year rule for conversion to indefinite contracts (Labor Contracts Act Art. 18) and understand that sector-specific exceptions (like the University Teacher Term Law's 10-year rule) are interpreted narrowly and require meeting specific statutory criteria beyond just the job title. Ensure non-renewal clauses are clear but understand they may be invalidated if deemed abusive under Article 19.

- Stay Updated on Legal Changes: Japanese labor laws and related regulations continue to evolve. For instance, rules regarding the mandatory disclosure of working conditions upon hiring and contract renewal were expanded in April 2024, requiring clearer specification of potential changes in job scope and location, and details about renewal limits and indefinite conversion rights for fixed-term employees.

Proactive compliance, fair treatment, clear communication, and robust documentation are essential for foreign companies managing employees effectively and minimizing legal risks within the Japanese labor law framework.

- Setting the Stage for Respect: Addressing Harassment in Japan’s Entertainment Industry

- A Step Towards Inclusion: Japan’s Supreme Court Rules on Transgender Employee Restroom Access

- Japan’s 2024 Work-Style Reform: Overtime Caps, Sector Shortages & Compliance Guide

- MHLW Guidelines on Managing Side-Jobs and Working-Hour Aggregation (Japanese)

- MHLW Q&A on Fixed-Term Contract Conversion (Japanese)