Exclusionary Practices under Japan’s Antimonopoly Act: A Compliance Guide for Dominant Firms

TL;DR

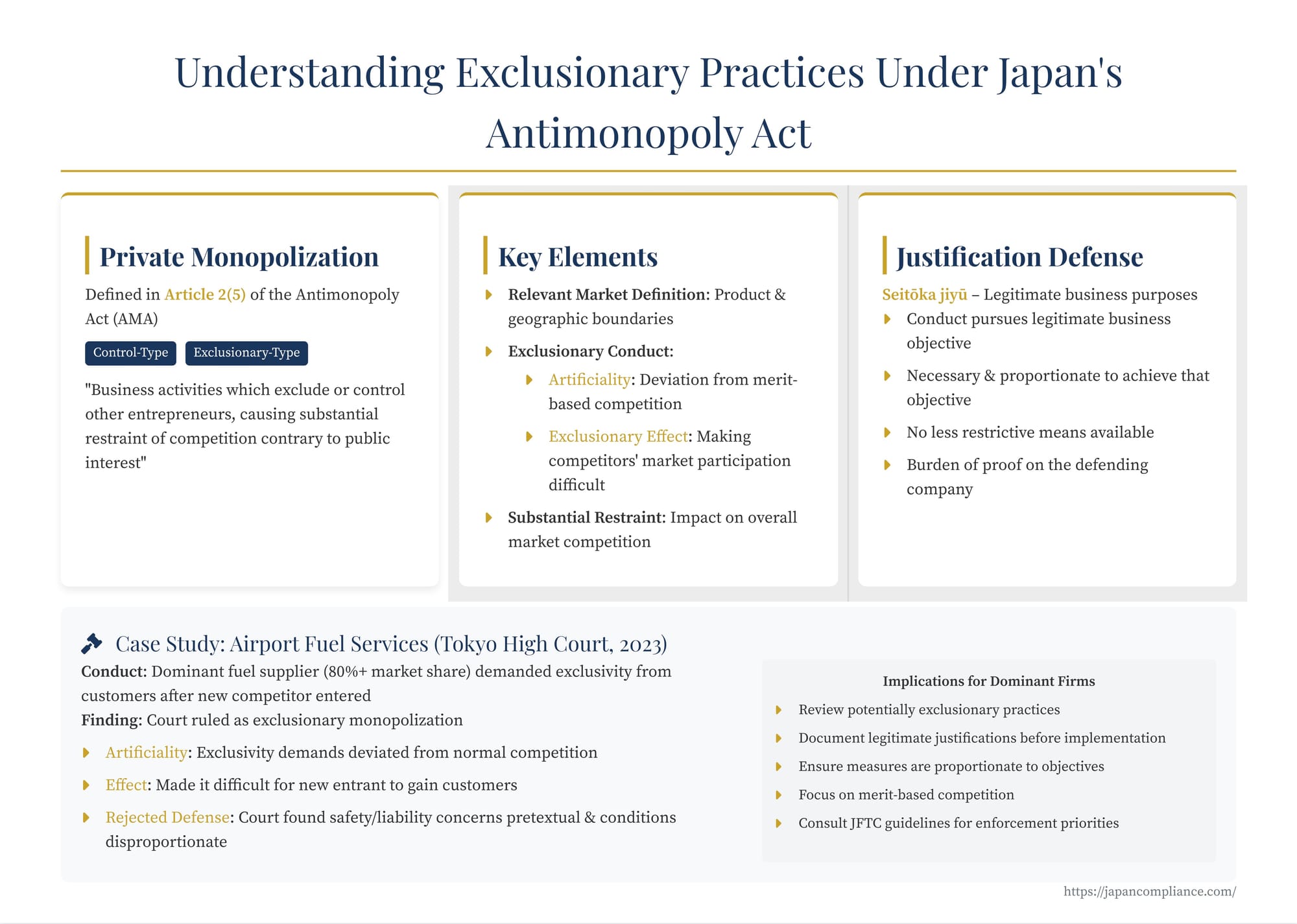

Japan’s Antimonopoly Act (AMA) bans “exclusionary private monopolization” by dominant firms—conduct that artificially hinders rivals and substantially restrains competition. To stay compliant, define markets carefully, vet any practice that could impede rivals, and document genuine business justifications. A 2023 Tokyo High Court decision on airport fuel services illustrates how the Japan Fair Trade Commission and courts analyse artificiality, exclusionary effect, and the narrow “justification” defence.

Table of Contents

- What is "Private Monopolization"?

- Key Elements of Exclusionary Private Monopolization

- The "Justification" Defense

- Illuminating Exclusionary Practices: A Case Study (Anonymized Airport Fuel Services)

- Implications for Dominant Firms in Japan

- Conclusion

Japan's Act on Prohibition of Private Monopolization and Maintenance of Fair Trade (commonly known as the Antimonopoly Act or AMA) serves as the cornerstone of competition law in the country. Article 3 of the AMA broadly prohibits unreasonable restraints of trade (such as cartels) and unfair trade practices. Crucially for companies holding significant market positions, it also prohibits "private monopolization." For US companies operating in or entering the Japanese market, understanding the scope of this prohibition, particularly concerning exclusionary conduct, is vital for ensuring compliance and navigating competitive interactions.

What is "Private Monopolization"?

Private monopolization is defined in Article 2(5) of the AMA. It refers to business activities by which any entrepreneur, individually or through combination or conspiracy with others, excludes or controls the business activities of other entrepreneurs, thereby causing, contrary to the public interest, a substantial restraint of competition in any particular field of trade.

This definition encompasses two broad categories:

- Control-Type Private Monopolization: Where a dominant firm controls the business activities of other firms (e.g., through shareholding, interlocking directorates, or coercive influence) to dictate their market behavior.

- Exclusionary-Type Private Monopolization: Where a firm engages in conduct that impedes or eliminates competitors, making it difficult for them to enter or remain in the market.

This article focuses primarily on the latter category – exclusionary practices – which often pose complex challenges for dominant firms.

Key Elements of Exclusionary Private Monopolization

Establishing exclusionary private monopolization under the AMA involves proving several key elements, guided by case law and guidelines from the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC), the primary enforcement agency.

- Relevant Market Definition: As in most competition law analyses, the first step is defining the relevant product and geographic market(s). This involves identifying the scope within which competition occurs, considering factors like product substitutability from both the demand and supply sides, and the geographic area where competitive conditions are sufficiently homogenous.

- Exclusionary Conduct: This is the core of the violation. The conduct must be shown to "exclude... the business activities of other entrepreneurs." Japanese jurisprudence, particularly influential Supreme Court decisions involving telecommunications (NTT East case, December 17, 2010) and copyright management (JASRAC case, April 28, 2015), has established a key test for exclusionary conduct. It requires demonstrating both:

- Artificiality (or Deviation from Normal Competition): The conduct must go beyond legitimate competitive activities and be artificial in nature, deviating from competition based on merits (price, quality, service). It's about how a company competes, not just the outcome.

- Exclusionary Effect: The conduct must have the effect of making it difficult for competitors to enter or continue operating in the market, thereby potentially harming the competitive process. This doesn't necessarily mean competitors must be completely eliminated, but their ability to compete effectively must be significantly hindered.

Examples of conduct scrutinized include discriminatory pricing, predatory pricing, refusal to supply essential inputs or access to essential facilities, tying arrangements, exclusive dealing requirements imposed on customers or distributors, and leveraging dominance from one market into another.

- Substantial Restraint of Competition: The exclusionary conduct must result in a "substantial restraint of competition" in the relevant market. This means the conduct must create, maintain, or strengthen a market situation where competition has significantly diminished, allowing the dominant firm (or firms) to control the market to some extent by influencing prices, quality, supply, or innovation, ultimately harming consumer welfare. It requires an impact on the overall market structure and competitive dynamics, not just harm to an individual competitor. Proving market dominance by the perpetrator, while not an explicit statutory element like "abuse of dominance" in the EU, is practically essential to demonstrate that their exclusionary conduct could lead to a substantial restraint of competition. High market share is a key indicator, but other factors like barriers to entry and countervailing buyer power are also considered.

- Contrary to the Public Interest: This element is generally considered fulfilled if a substantial restraint of competition is established.

The "Justification" Defense

Even if conduct appears to meet the criteria for exclusionary private monopolization, it might be deemed permissible if it is justified by legitimate business reasons. This defense, often referred to as seitōka jiyū, requires the company to demonstrate that:

- The conduct pursues a legitimate business objective (e.g., enhancing efficiency, ensuring safety, protecting intellectual property, meeting regulatory requirements).

- The conduct is necessary and proportionate to achieve that objective, and there are no less restrictive means available.

The burden of proving justification rests heavily on the company engaging in the conduct. Pretextual justifications aimed merely at harming competition will not suffice.

Illuminating Exclusionary Practices: A Case Study (Anonymized Airport Fuel Services)

A significant decision by the Tokyo High Court on January 25, 2023, provides valuable insights into how these principles are applied. The case involved allegations of exclusionary private monopolization in the market for aircraft fuel supply services (specifically, on-tarmac refueling) at a particular regional airport.

Background: A long-standing sole provider (the dominant firm) of these services faced entry by a new competitor. Following the competitor's entry, the dominant firm allegedly engaged in conduct aimed at hindering the newcomer's operations.

Alleged Conduct: The dominant firm was accused of:

- Notifying its existing customers that if they received fuel from the new competitor, they could no longer receive fuel from the dominant firm (effectively demanding exclusivity).

- Requiring customers who did use the competitor's fuel to sign documents absolving the dominant firm of liability for any issues arising from fuel mixing, or demanding that fuel tanks be completely emptied and cleaned before receiving fuel from the dominant firm again (imposing onerous conditions).

JFTC and Court Findings: The JFTC investigated and issued a cease-and-desist order and imposed a surcharge, finding the conduct constituted exclusionary private monopolization. The dominant firm challenged this in court.

The Tokyo High Court upheld the JFTC's findings, analyzing the key elements:

- Relevant Market: Defined narrowly as the on-tarmac aircraft fuel supply service at the specific airport in question.

- Dominance: The incumbent held a very high market share (over 80%), indicating significant market power.

- Exclusionary Conduct: The court assessed the "artificiality" and "exclusionary effect" of the incumbent's actions.

- Artificiality: Imposing exclusivity demands and discriminatory conditions on customers simply because they dealt with a competitor was deemed to deviate from normal competitive practices based on price or service quality. The court also considered evidence suggesting an exclusionary intent, viewing it as a factor supporting the finding of artificiality, although exclusionary intent itself is not a mandatory requirement.

- Exclusionary Effect: The conduct made it significantly difficult for the new entrant to acquire customers and operate effectively, directly hindering its ability to compete and gain a foothold in the market.

- Substantial Restraint of Competition: By restricting customer choice and hindering the new entrant, the incumbent's actions reinforced its dominant position and reduced competitive pressure in the market, leading to a substantial restraint of competition.

- Justification Defense: The dominant firm argued its actions were necessary to avoid liability risks associated with potentially mixed fuels from different suppliers. The court rejected this justification. It found a lack of credible evidence supporting the alleged safety/liability risks as the true motive. Furthermore, even if such concerns existed, the imposed conditions (exclusivity demands, tank draining) were deemed disproportionate and not the least restrictive means to address potential issues. The justification was seen as pretextual, masking an anti-competitive purpose.

This case underscores that even seemingly plausible business justifications will be scrutinized carefully. Dominant firms must ensure their actions are genuinely aimed at legitimate goals and are narrowly tailored to achieve them without unduly restricting competition.

Implications for Dominant Firms in Japan

The prohibition on exclusionary private monopolization under the AMA carries significant implications for companies with substantial market shares in Japan:

- Heightened Scrutiny: Practices that might be permissible for firms with less market power can be illegal under the AMA if engaged in by a dominant firm and have exclusionary effects.

- Review Business Practices: Dominant firms should proactively review practices that could potentially disadvantage competitors. This includes rebate structures (especially loyalty-inducing ones), exclusive dealing arrangements, tying, refusals to supply essential inputs or grant access to essential infrastructure, and discriminatory treatment.

- Legitimate Justifications: If a practice carries potential exclusionary risk, ensure there is a clear, documented, and legitimate business justification before implementation. This justification should be robust enough to withstand scrutiny.

- Objective Effects Matter: While exclusionary intent can be supporting evidence, the primary focus is on the objective nature (artificiality) and effect of the conduct on competition. Lack of subjective intent to harm competitors is not a defense if the conduct is objectively exclusionary and substantially restrains competition.

- Guidance: The JFTC publishes various guidelines (e.g., Guidelines Concerning Private Monopolization under the Antimonopoly Act, Guidelines Concerning Distribution Systems and Business Practices) that provide valuable insights into its enforcement priorities and analytical approaches.

Conclusion

Japan's Antimonopoly Act prohibits dominant firms from engaging in exclusionary practices that artificially hinder competitors and substantially restrain competition. The focus is on maintaining a competitive process based on merit, not allowing powerful incumbents to entrench their position through anti-competitive means. As illustrated by court decisions like the anonymized airport fuel case, the assessment involves analyzing the "artificiality" of the conduct (deviation from normal competition) and its "exclusionary effect" on competitors and the market. While a justification defense exists, it is interpreted narrowly and requires demonstrating that the conduct is genuinely necessary and proportionate to achieve a legitimate objective. For US and other foreign companies holding or aspiring to significant market positions in Japan, a thorough understanding of these principles and proactive assessment of their business practices are essential to ensure compliance and foster fair competition.