Understanding Compensation for Detention in Japanese Juvenile Cases: The 1991 Supreme Court Decision

Decision Date: March 29, 1991

Introduction

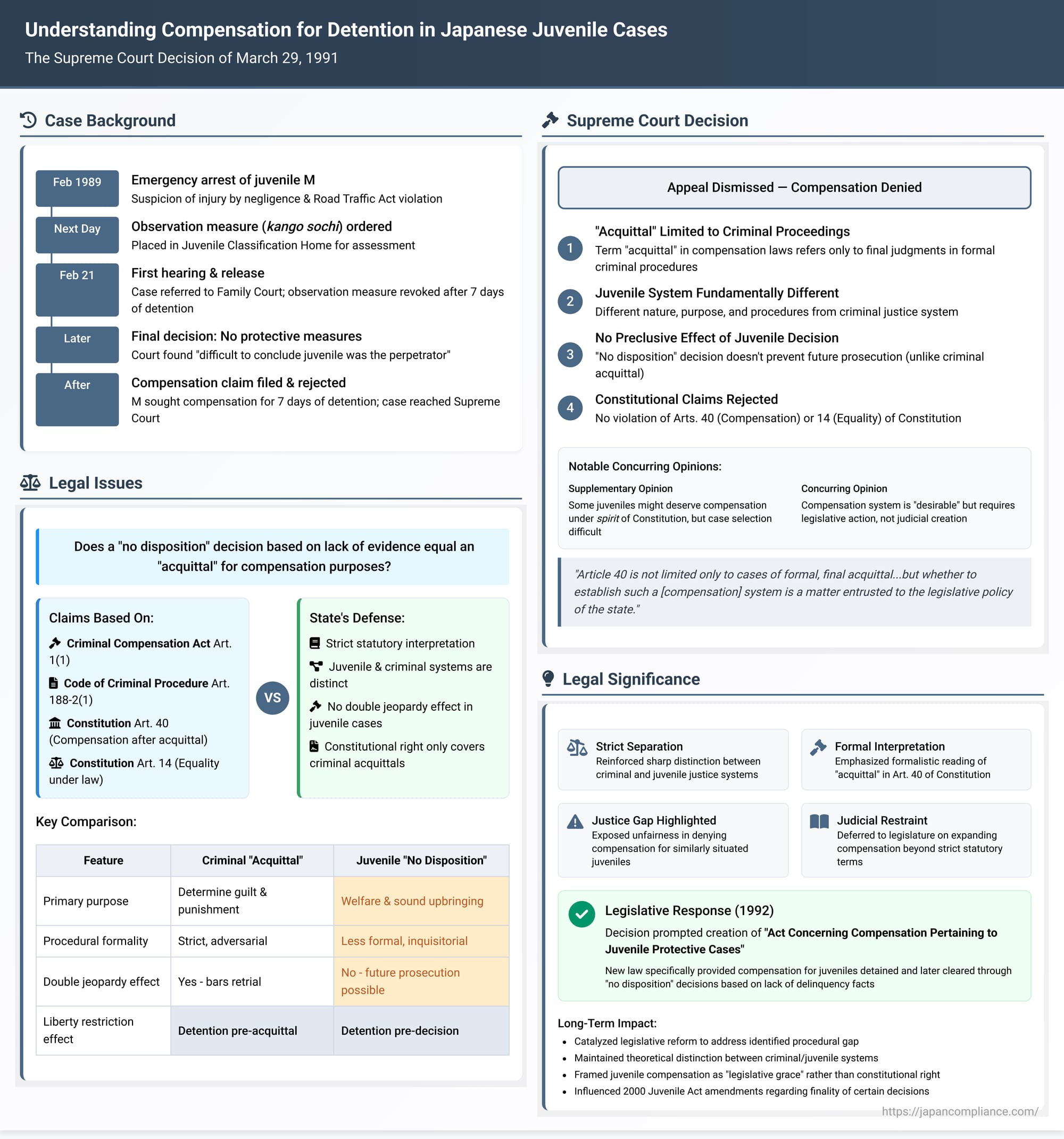

On March 29, 1991, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant decision concerning the scope of state compensation for individuals detained but ultimately not subjected to protective measures within the juvenile justice system. The case, originating from a special appeal against a lower court's dismissal of a compensation claim, delved into the fundamental differences between Japan's criminal procedure and its distinct juvenile justice proceedings, particularly concerning the interpretation of "acquittal" under the Constitution and relevant statutes. This ruling highlighted a crucial legal question: Does a juvenile court's decision not to impose protective measures, based on a finding that the alleged delinquency was not substantiated, equate to an acquittal in the criminal sense, thereby triggering the right to compensation for pre-decision detention?

Factual Background

The case involved an individual, anonymized here as M, who was a minor at the time of the incident. In February 1989, M was emergently arrested on suspicion of causing injury through professional negligence and violating the Road Traffic Act. The following day, instead of seeking a standard pre-indictment detention order from a judge as would typically occur in an adult criminal case, the public prosecutor requested an "observation measure" (kango sochi) under Article 43 of the Juvenile Act. This measure, unique to the juvenile system, allows for the juvenile to be placed in a Juvenile Classification Home (shōnen kanbetsusho) for assessment. M was consequently detained in such a facility.

Several days later, on February 21, 1989, M's case was referred to the Family Court, the specialized court handling juvenile matters in Japan. The first hearing (shinpan) was held that same day. After examining a witness, the Family Court decided to revoke the observation measure, and M was released from the Juvenile Classification Home. M had been detained for a total of seven days.

Subsequently, after further hearings, the Family Court ultimately issued a decision not to subject M to any protective measures (fushobun kettei) under Article 23, Paragraph 2 of the Juvenile Act. The reason provided for this decision was crucial: the court determined that it was "difficult to conclude that the juvenile was the perpetrator," effectively finding that the alleged facts constituting delinquency (hikō jijitsu) were not proven.

The Claim for Compensation

Following this non-disposition decision, M sought compensation from the state for the seven days of detention endured between the arrest and the revocation of the observation measure. The claim was twofold:

- Criminal Compensation: Based on the Criminal Compensation Act (Act No. 1 of 1950) (Keiji Hoshō Hō). Article 1, Paragraph 1 of this Act provides that a person who has received an "acquittal" (muzai no saiban) in ordinary criminal proceedings, retrial, or extraordinary appeal proceedings is entitled to compensation for pre-trial detention (miketsu no yokuryū mata wa kōkin).

- Cost Compensation: Based on the Code of Criminal Procedure (Keiji Soshō Hō). Article 188-2, Paragraph 1 provides for the state to compensate necessary costs (such as attorney fees) when a "judgment of acquittal" (muzai no hanketsu) becomes final and binding.

M argued that the Family Court's non-disposition decision, grounded in the lack of evidence for the alleged delinquency, should be interpreted as substantially equivalent to an "acquittal" as contemplated by both the Criminal Compensation Act and the Code of Criminal Procedure. The core of the argument was that a formal determination of non-delinquency is functionally the same as a finding of innocence in a criminal trial.

Furthermore, M contended that failing to recognize this equivalence and denying compensation would violate the Constitution of Japan. Specifically, the arguments invoked:

- Article 40: "Any person, in case he is acquitted after he has been arrested or detained, may sue the State for redress as provided by law." M argued that the term "acquitted" (muzai no saiban) in the Constitution should encompass not just formal acquittals in criminal trials but any judicial determination confirming the absence of grounds for the initial detention, including a non-disposition decision based on lack of delinquency facts.

- Article 14: "All of the people are equal under the law and there shall be no discrimination in political, economic or social relations because of race, creed, sex, social status or family origin." The argument here likely centered on the idea that treating juveniles detained and later cleared differently from adults in similar situations regarding compensation constituted unreasonable discrimination.

Lower Court Decisions

The Family Court, as the court of first instance for the compensation claim, rejected M's request. Its reasoning was based on a strict interpretation of the relevant laws:

- The Criminal Compensation Act and the Code of Criminal Procedure explicitly refer to compensation following proceedings under the Code of Criminal Procedure.

- Juvenile protective proceedings (hogo tetsuzuki) operate under the Juvenile Act, aiming primarily at the sound upbringing of juveniles, a different philosophy and procedural framework than criminal proceedings which focus on punishment.

- Therefore, a non-disposition decision due to lack of delinquency facts in a juvenile proceeding cannot be equated with an acquittal in a criminal proceeding. Applying or analogizing the compensation provisions was deemed impermissible.

M immediately appealed (sokuji kōkoku) this decision to the High Court, which also dismissed the appeal, upholding the Family Court's reasoning. M then filed a special appeal (tokubetsu kōkoku) to the Supreme Court, reiterating the constitutional arguments and the claim that "acquittal" should be interpreted substantively to include non-disposition decisions based on factual innocence.

The Supreme Court's Decision and Rationale

The Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, dismissed M's special appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions. The core reasoning revolved around the distinct nature of juvenile proceedings compared to criminal proceedings under the Code of Criminal Procedure.

1. Interpretation of "Acquittal" in Compensation Laws:

The Court held that the term "acquittal" (muzai no saiban) as used in Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the Criminal Compensation Act clearly refers, based on the text of the paragraph and related provisions, to a final and binding judgment of acquittal obtained through procedures defined by the Code of Criminal Procedure.

2. Distinction Between Juvenile and Criminal Proceedings:

The Court emphasized the fundamental differences between the two systems:

- Nature and Purpose: Criminal proceedings aim to determine guilt and impose punishment based on criminal responsibility. Juvenile proceedings, governed by the Juvenile Act, prioritize the welfare and sound upbringing of the minor, focusing on protective measures rather than punishment, even when delinquency is found.

- Procedure: The procedures differ significantly. Juvenile hearings (shinpan) are generally less formal and adversarial than criminal trials.

3. Lack of Preclusive Effect (Res Judicata/Double Jeopardy):

Critically, the Court noted that a non-disposition decision (fushobun kettei) in juvenile proceedings does not have the effect of preventing subsequent criminal prosecution or further proceedings in the Family Court for the same alleged conduct. This lack of finality, in the sense understood in criminal law (where an acquittal bars retrial for the same offense under Article 39 of the Constitution – double jeopardy), was a key factor distinguishing it from a criminal acquittal. The court cited established precedent from the Supreme Court's Grand Bench (Decision of April 28, 1965, Case No. (A) 2176 of 1962; Keishu Vol. 19, No. 3, p. 240) which held that the double jeopardy protection of Article 39 does not apply to decisions like non-commencement of hearing (shinpan fukaishi kettei) in juvenile cases, implying a similar logic applies to non-disposition decisions.

4. Conclusion on Statutory Interpretation:

Based on these distinctions – the different procedural framework and the lack of preclusive effect – the Court concluded that a non-disposition decision, even if based on the ground that the facts constituting delinquency were not proven, does not fall under the definition of "acquittal" (muzai no saiban) in Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the Criminal Compensation Act.

Similarly, the Court held that such a decision does not constitute a "judgment of acquittal" (muzai no hanketsu) as required by Article 188-2, Paragraph 1 of the Code of Criminal Procedure for cost compensation.

5. Constitutional Arguments:

The Court summarily dismissed the constitutional arguments, stating that interpreting the compensation laws in this manner does not violate Article 40 (Right to compensation after acquittal) or Article 14 (Equality under the law). This conclusion was reached by referencing the aforementioned Grand Bench precedents, indicating adherence to a consistent line of interpretation that differentiates the constitutional protections applicable in criminal versus juvenile proceedings, particularly concerning the scope of "acquittal" and double jeopardy. The Court essentially adopted a formalistic interpretation of "acquittal" in Article 40, limiting it to acquittals within the criminal justice system as defined by statute.

Supplementary and Concurring Opinions

While the decision was unanimous in its outcome (dismissing the appeal), two justices provided separate opinions offering additional perspectives, hinting at the underlying complexities and potential need for legislative reform.

1. Supplementary Opinion:

One Justice acknowledged the majority's reasoning that a non-disposition decision cannot be equated with a criminal acquittal under existing law. However, this Justice added a significant point: It cannot be denied that some cases resulting in a non-disposition decision due to lack of delinquency facts might well have resulted in a formal acquittal if they had been processed through the criminal justice system.

From a legislative policy standpoint (rippōron to shite wa), this Justice suggested that providing treatment analogous to criminal compensation for juveniles who were detained before receiving such a non-disposition decision might indeed align with the spirit (seishin) of Article 40 of the Constitution. Nevertheless, the Justice also noted the practical difficulty: since these cases do not go through formal criminal proceedings, selecting which non-disposition cases warrant compensation would be challenging. Simply granting compensation to all cases of non-disposition due to lack of delinquency facts might not be appropriate. Ultimately, the Justice concluded that under the current legal framework, there was no room to grant M's claim.

2. Concurring Opinion:

Another Justice agreed with the conclusion to dismiss the appeal but offered a different perspective on the relationship between the Criminal Compensation Act and Article 40 of the Constitution.

This Justice argued that the view that the Criminal Compensation Act does not apply to juvenile protective measures is a correct interpretation of the statute itself. The Act specifically provides compensation for measures within criminal proceedings (pre-trial detention, execution of sentence, etc.). Given that the Juvenile Act distinguishes between protective cases (hogo jiken) and criminal cases (keiji jiken), the non-application of the Criminal Compensation Act to the former is legally sound. Therefore, the mere fact that the Act doesn't provide for compensation related to detention-like measures in juvenile cases does not, in itself, automatically create a constitutional issue under Article 40.

However, this Justice held a broader interpretation of the purpose (shushi) of Article 40. It was argued that Article 40 is not limited only to cases of formal, final acquittal. Rather, it establishes the principle that individuals can seek compensation from the state whenever it becomes clear that the state's restriction of their liberty through public authority was baseless, leading to a situation substantively equivalent (jisshitsujō...dōyō ni kaisareru baai) to receiving a final acquittal.

Applying this interpretation, the Justice believed it was certainly possible, and indeed desirable (nozomashii koto), for the state to establish a compensation system for situations like the present case – where a non-disposition decision under the Juvenile Act is based on the lack of delinquency facts. However, the critical point was that whether or not to establish such a system is a matter entrusted to the legislative policy (rippō seisaku) of the state. Since no such legislative system existed at the time, M's claim, based solely on the existing Criminal Compensation Act, had to be deemed unfounded.

These opinions, while not altering the legal outcome for M, clearly signaled judicial awareness of a potential gap in the legal framework and pointed towards the legislature as the appropriate body to address it.

Legal Context, Significance, and Post-Decision Developments

This 1991 Supreme Court decision rests heavily on the traditional Japanese legal understanding of the separation between the criminal justice system and the juvenile justice system.

- Distinct Systems: The criminal system focuses on guilt, responsibility, and punishment, adhering strictly to the Code of Criminal Procedure and constitutional guarantees like Article 39 (double jeopardy) and Article 40 (compensation upon acquittal). The juvenile system, under the Juvenile Act, emphasizes the child's welfare, education, and rehabilitation through "protective measures," operating with different procedures and goals. This distinction was fundamental to the Court's refusal to equate a non-disposition decision with a criminal acquittal.

- Scope of Article 40: The decision reaffirmed the prevailing, more restrictive judicial interpretation of "acquittal" in Article 40, tying it to the formal outcomes of criminal proceedings as defined by law. This contrasts with broader academic views suggesting Article 40 should cover any situation where detention is proven unjustified.

- Kango Sochi (Observation Measure): The case involved detention under this specific measure. Unlike standard criminal detention aimed at preventing flight or evidence tampering, kango sochi is primarily for the Juvenile Classification Home to assess the juvenile's character, environment, and needs to inform the Family Court's decision. However, it is undeniably a form of deprivation of liberty.

- Lack of Finality: The fact that a non-disposition decision did not bar future prosecution or proceedings was a significant legal hurdle for the appellant. It meant the decision wasn't "final" in the way a criminal acquittal is typically understood.

The decision, particularly the supplementary and concurring opinions, brought the issue of compensation for unjustly detained juveniles into sharp focus. The perceived unfairness (fukōhei sa) of denying compensation to a juvenile detained for a week and then effectively cleared, simply because they were processed under the Juvenile Act instead of the Code of Criminal Procedure, became more apparent.

This led directly to legislative action. Spurred by this decision, the Diet enacted the Act Concerning Compensation Pertaining to Juvenile Protective Cases (Act No. 84 of 1992) (Shōnen no Hogo Jiken ni Kakaru Hoshō ni Kansuru Hōritsu), often referred to as the Juvenile Compensation Act. Key features of this Act include:

- Purpose: It aims to provide compensation from the perspective of "distributive justice" (haibun teki seigi) in a standardized and prompt manner. It is generally interpreted similarly to the Criminal Compensation Act but is explicitly framed not as a direct requirement of Article 40 of the Constitution.

- Scope: It covers situations where a juvenile was subjected to an observation measure (kango sochi) or certain other restrictive measures, and subsequently, it is determined that the grounds for such measures did not exist (e.g., a non-disposition decision based on lack of delinquency facts).

- Procedure: Unlike the Criminal Compensation Act where the individual has a right to claim compensation (seikyūken), under the Juvenile Compensation Act, the compensation decision is made by the Family Court based on its own authority (shokken), although the juvenile or their representative can file a "request" (mōshide) to prompt the court to exercise this authority. This procedural difference reflects the underlying legal theory that this compensation is a matter of legislative grace rather than a direct constitutional entitlement stemming from Article 40.

Therefore, while M's specific claim failed under the laws existing in 1991, the case served as a catalyst for creating the very legal mechanism that would provide compensation in similar future situations.

It is also worth noting that the Juvenile Act itself has undergone revisions since this decision. For instance, amendments in 2000 introduced Article 46, Paragraph 2, which grants a limited res judicata effect (precluding further protective proceedings or criminal prosecution for the same facts) to non-disposition decisions in certain serious cases where a public prosecutor participated in the juvenile hearing (kensatsukan kan'yo jiken). This change addressed the "lack of finality" issue to some extent, but only for a specific category of cases, reflecting the ongoing tension and evolution in balancing due process rights and the protective goals within the juvenile system. The fundamental distinction between the two systems, highlighted in the 1991 decision, largely remains.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1991 decision in the case of M underscores the significant legal distinctions drawn in Japan between criminal proceedings and juvenile protective proceedings. By strictly interpreting "acquittal" in the context of compensation laws to refer only to outcomes within the formal criminal justice system, the Court denied compensation to a juvenile detained and later cleared in the juvenile system. The Court reasoned that the differing nature, purpose, and lack of preclusive effect of juvenile proceedings prevented equating a non-disposition decision based on lack of delinquency with a criminal acquittal under the then-existing statutes and constitutional precedents. While legally grounding its decision in established principles separating the two systems, the Court, through the supplementary and concurring opinions, acknowledged the potential gap in justice. This judicial recognition paved the way for the legislature to act, resulting in the Juvenile Compensation Act of 1992, which prospectively addressed the specific issue raised by M's case, albeit framing it as a matter of legislative policy rather than a direct constitutional right under Article 40. The case remains a key landmark illustrating the interplay between constitutional rights, statutory interpretation, the distinct philosophies of Japan's justice systems, and the role of the judiciary in prompting legislative reform.