Trustee's Claim vs. "Unlawful Cause" Defense: Supreme Court Favors Equity in Pyramid Scheme Bankruptcy

On October 28, 2014, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment addressing a bankruptcy trustee's power to recover funds distributed by a bankrupt company through an illegal pyramid scheme. The Court ruled that a participant who received profits from such a scheme cannot use the "benefit conferred for an unlawful cause" defense under Civil Code Article 708 to resist the trustee's claim for unjust enrichment, when doing so would be contrary to the principle of good faith, especially considering the losses of other victimized members.

Factual Background: The Pyramid Scheme, Payments, and Bankruptcy

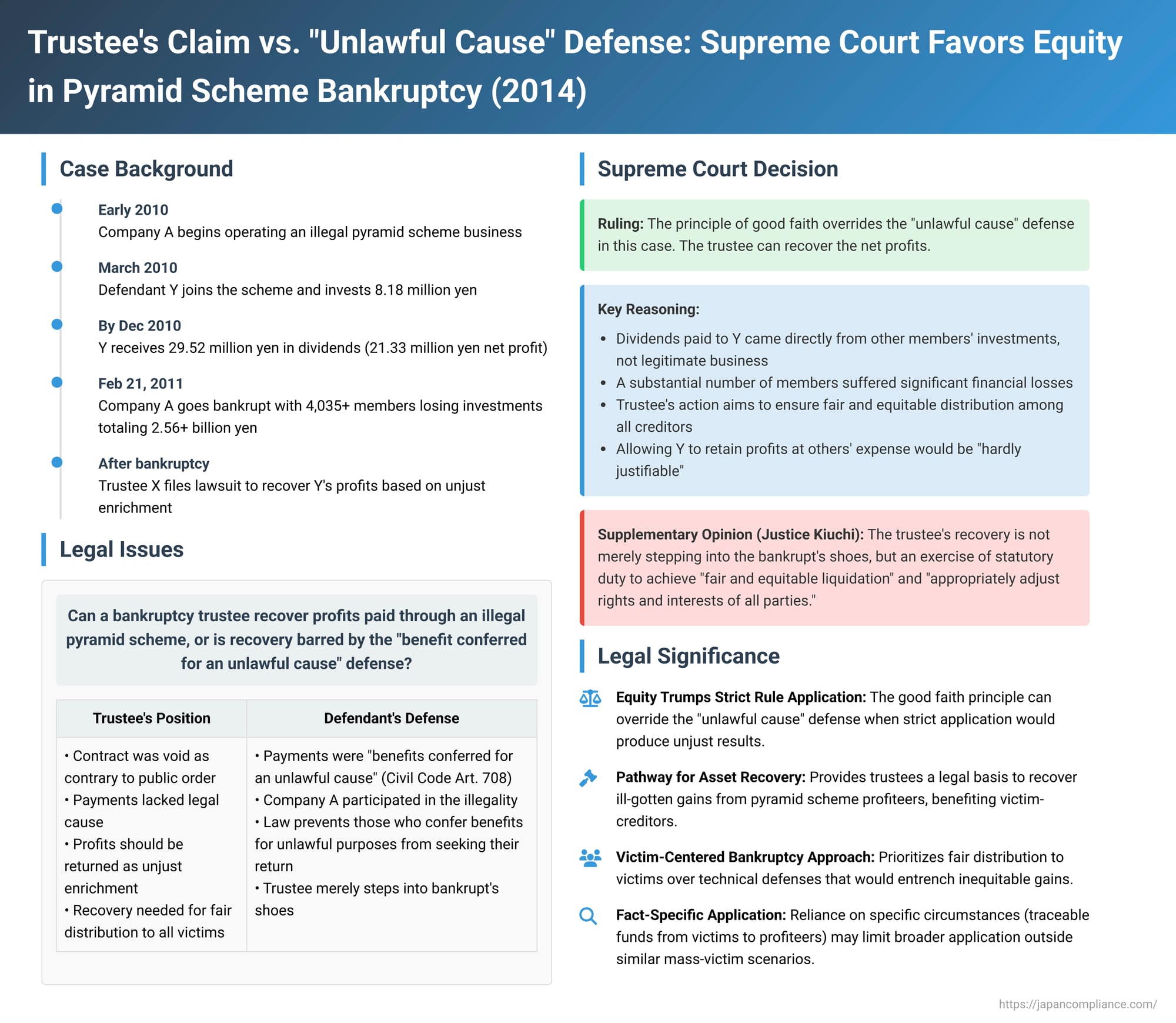

The case involved A Company, which, from around 2010, operated a business identified as an illegal pyramid scheme (無限連鎖講 - mugen rensa kō). Such schemes, prohibited under the Act on Prevention of Endless Chain Schemes, primarily use funds collected from new participants to pay dividends to earlier participants, rather than generating legitimate profits.

Y, the appellee (defendant), entered into a contract to become a member of A Company's scheme in March 2010. By December of that year, Y had invested a total of 8,184,200 yen into the scheme. During the same period, Y received dividend payments from A Company amounting to 29,517,035 yen, resulting in a net profit of 21,332,835 yen.

A Company managed to attract at least 4,035 members, collecting investments totaling over 2.56 billion yen. However, the scheme inevitably collapsed, and on February 21, 2011, A Company had bankruptcy proceedings initiated against it. X, the appellant (plaintiff), was appointed as A Company's bankruptcy trustee.

Trustee X subsequently filed a lawsuit against Y. X argued that the contract between A Company and Y was void as being contrary to public order and good morals. Based on the theory of unjust enrichment, X sought the return of the net profit Y had received from the scheme (the 21,332,835 yen, referred to by the Supreme Court as "these dividends"), plus damages for delay.

The first instance court and the High Court both acknowledged that the contract was void and that the payments made to Y lacked legal cause. However, they dismissed trustee X's claim. Their reasoning was that the dividends paid to Y constituted a "benefit conferred for an unlawful cause" (不法原因給付 - fuhō gen'in kyūfu) as per Article 708 of the Civil Code. This article generally bars the provider of such a benefit (in this case, A Company, and by extension, its trustee) from demanding its return. Trustee X then successfully petitioned the Supreme Court for an appeal.

The Legal Obstacle: "Benefit Conferred for an Unlawful Cause" (Civil Code Article 708)

Article 708 of the Japanese Civil Code stipulates that a person who has tendered performance for an unlawful cause cannot demand the return of the thing tendered. There is an exception if the unlawful cause existed only on the part of the person who received the benefit, but that was not considered the situation here regarding the initial payments.

The primary purpose of this rule is to deter illegal transactions by refusing to lend the court's assistance to parties who knowingly engage in them. It effectively means that the law will leave the parties where it finds them. Applied directly, this would prevent A Company itself from recovering the dividends it paid to Y, as the payments were part of an illegal pyramid scheme. The crucial question for the Supreme Court was whether A Company's bankruptcy trustee, X, was similarly barred.

The Supreme Court's Good Faith Override

The Supreme Court reversed the decisions of the lower courts and ruled in favor of trustee X, ordering Y to return the net dividends. The Court's decision was not based on a reinterpretation of the trustee's general legal status that would always allow them to bypass Article 708, but rather on the application of the principle of good faith (信義則 - shingi soku) to the specific circumstances of this case.

The Court reasoned as follows:

- Source of Y's Profits: The dividends paid to Y under the illegal pyramid scheme were not generated from legitimate business activities but were sourced from the funds invested by other members of the scheme.

- Widespread Victimization: A substantial number of A Company's members suffered significant financial losses, having invested money but received little or nothing in return before the scheme's collapse. These losing members constituted the majority of the creditors in A Company's bankruptcy.

- Trustee's Objective: Equitable Distribution: Trustee X's action in seeking the return of Y's profits was aimed at recovering these funds for the bankruptcy estate. The purpose was to facilitate a fair and equitable liquidation, including distributing these recovered assets among all bankruptcy creditors, notably the numerous members who had lost their investments. The Court found this objective to be consistent with principles of equity.

- Unconscionability of Y Retaining Profits: The Court concluded that allowing Y to retain these profits by invoking the "unlawful cause" defense against the bankruptcy trustee would effectively endorse Y's unjust enrichment at the direct expense of the other victimized members. Such an outcome, the Court stated, would be "hardly justifiable."

Therefore, the Supreme Court held that, under these specific circumstances, it would be contrary to the principle of good faith for Y to assert the "unlawful cause" doctrine of Civil Code Article 708 as a reason to refuse repayment to bankruptcy trustee X.

The Role and Status of the Bankruptcy Trustee

In a supplementary opinion, Justice Kiichi Kiuchi further elaborated on the trustee's role. He emphasized that the bankruptcy trustee's claim for recovery is not merely an act of stepping into the bankrupt company's shoes. Instead, it is an exercise of the trustee's statutory duty under the Bankruptcy Act to achieve a "fair and equitable liquidation" of the debtor's assets and to "appropriately adjust the rights and interests of creditors and other interested parties."

Justice Kiuchi also pointed out that funds recovered by a trustee in such situations are added to the bankruptcy estate for distribution to creditors. They do not, in practice, revert to the bankrupt entity itself, especially a corporation involved in an illegal scheme that will likely cease to exist. Thus, allowing the trustee's claim does not equate to providing legal protection to the perpetrator of the illegal scheme. Denying the trustee's claim, conversely, would allow those who profited from the illegal scheme at others' expense to retain their gains, a result that the principle of good faith aims to prevent when the trustee acts to ensure a fair adjustment among all stakeholders.

Implications of the Decision

This Supreme Court judgment has important implications, particularly in bankruptcies arising from illegal investment schemes or pyramid operations that result in widespread financial harm:

- Path for Recovery: It provides a pathway for bankruptcy trustees to recover ill-gotten gains from participants who profited from such schemes, even when the payments might otherwise be shielded by the "unlawful cause" doctrine.

- Equity via Good Faith: The decision demonstrates the power of the good faith principle as a flexible legal tool to achieve equitable outcomes in bankruptcy, potentially overriding the strict application of other statutory rules when such application would lead to unjust results.

- Focus on Victims and Fair Distribution: The Court's reasoning heavily emphasized the source of the funds (other members' investments) and the ultimate destination of the recovered assets (fair distribution to all creditors, including those victimized by the scheme). This highlights a victim-centric approach in the context of collective redress through bankruptcy.

- Limited Scope?: Legal commentators have noted that the decision's reliance on the specific facts—an illegal pyramid scheme with clearly identifiable victims among the creditors and funds traceable from one group of members to another—might mean its direct applicability is strongest in similar mass-victim scenarios. The extent to which this good faith override of Article 708 might apply in other "unlawful cause" situations involving bankruptcy remains to be seen.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 2014 decision represents a pragmatic and equity-driven approach to a complex legal problem. While Civil Code Article 708 generally serves to discourage illegal activities by preventing participants from seeking judicial remedies for their return, this ruling demonstrates that its application is not absolute. When a bankruptcy trustee, acting to ensure a fair and equitable distribution for all creditors (many of whom are victims of the bankrupt's illegal enterprise), seeks to recover funds from those who profited from that same illegality, the principle of good faith can intervene to prevent an unjust outcome. This judgment underscores the bankruptcy system's capacity to adapt general civil law principles to achieve its overarching goals of fairness and equitable treatment for all stakeholders.