Trial by Surprise? The "Yodo-go Hijacking" Case and the Court's Duty to Clarify Shifting Focus

Date of Judgment: December 13, 1983

Introduction

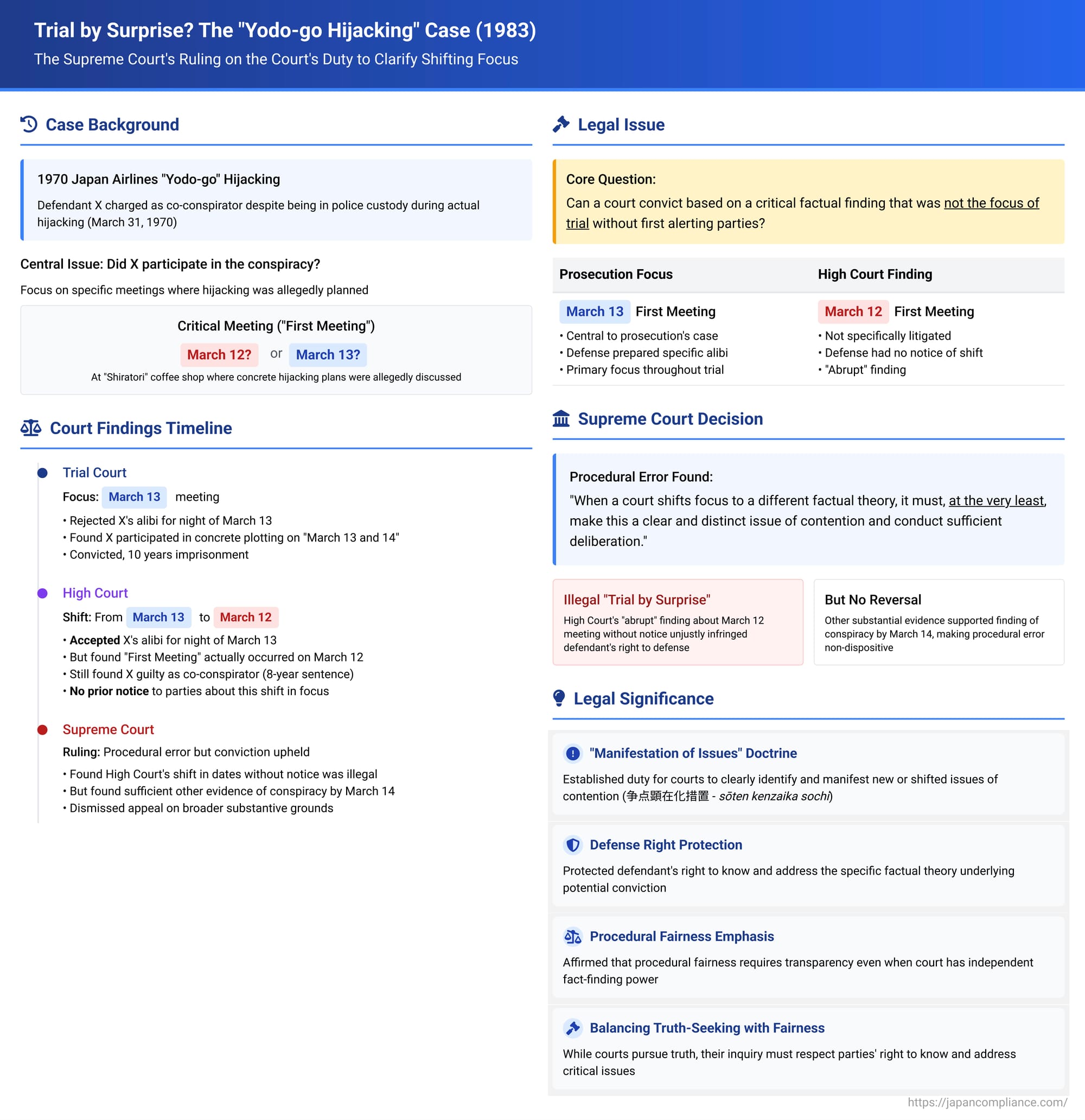

In a criminal trial, particularly one involving complex conspiracies, the focus of evidentiary dispute often narrows down to specific critical facts. Both the prosecution and the defense concentrate their efforts on proving or disproving these pivotal points. But what happens if an appellate court, while reviewing the case, begins to doubt the trial court's finding on such a central fact and considers convicting the defendant based on an alternative factual scenario that was not the primary focus of the trial? Can the court do so without first alerting the parties and giving the defense a fair opportunity to address this new angle? This crucial issue of procedural fairness was at the heart of a 1983 Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, decision in the appeal of a defendant convicted in relation to the infamous "Yodo-go Hijacking" incident.

Factual Background: The Yodo-go Hijacking and a Shifting Conspiracy Timeline

The defendant, X (anonymized as Y. Maeda in the original), was charged as a co-principal in the 1970 hijacking of Japan Airlines flight "Yodo-go" by members of the "Communist League, Red Army Faction" (共産主義者同盟赤軍派 - Kyōsanshugisha Dōmei Sekigun-ha). The charges included robbery causing injury, abduction for transport out of the country, and unlawful confinement.

It was undisputed that the hijacking itself was carried out by members of the Red Army Faction, led by T. Tamiya and T. Konishi, on March 31, 1970. It was also clear that at the time of the hijacking, defendant X, along with S. Shiomi (the ideological leader of the Red Army Faction), was already in police custody for a separate incident (the "Daibosatsu Pass Incident" involving explosives). Thus, X had not participated in the physical execution of the hijacking.

The central issue from the first instance trial onwards was whether X had participated in a conspiracy (kyōbō) with Shiomi, Tamiya, Konishi, and others to carry out the Yodo-go hijacking, sufficient to hold him liable as a co-principal.

- Prosecution's Initial Allegations and Clarifications:

- Initially, the prosecutor broadly alleged the conspiracy occurred from around January 7, 1970, until the hijacking, with successive conspiracy (junji kyōbō) after March 15. The alleged locations included Hotel Aikawa and the "Shiratori" coffee shop.

- In their opening statement at the second trial session, the prosecutor narrowed the focus, claiming that X, along with Shiomi and Tamiya, engaged in "concrete plotting" (gutaiteki bōgi) for the hijacking between March 12 and March 14, 1970, at places including the "Shiratori" coffee shop. This involved discussions on the timing, means, methods, and perpetrators of the hijacking, as part of a broader "Phoenix Operation" (for establishing an international base) supported by weapons procurement ("Untouchable Operation") and fundraising ("Mafia Operation") activities in which X played a significant role. This clarification effectively pinpointed these three days as crucial for establishing X's involvement in the specific hijacking plot.

- The Trial's Focus on the "First Meeting" (March 13):

The defense vehemently contested X's participation in any such plotting. During the trial, the prosecution's key evidence for X's involvement in the concrete hijacking plot centered on prosecutorial depositions from X and Shiomi. These depositions stated that on the night of March 13 at the "Shiratori" coffee shop, Shiomi and Tamiya first revealed their firm intention to hijack a plane, showed X a memo with details, and explained the specific methods.- Consequently, this alleged meeting on the night of March 13 (referred to as the "First Meeting" - 第一次協議, Dai-ichiji Kyōgi) became the paramount point of contention. The defense focused heavily on establishing an alibi for X for that specific night, arguing he was visiting an acquaintance, Y. Tokoro, and also met an old friend, S. Ando, at that time.

- First Instance Judgment: The trial court largely accepted the prosecution's narrative about the lead-up to the hijacking, including X's activities on March 12 and the daytime of March 13. It rejected X's alibi for the night of March 13 and found that X had engaged in the concrete hijacking plot with Shiomi, Tamiya, and Konishi on "March 13 and the following March 14, at the 'Shiratori' coffee shop, etc." X was convicted and sentenced to 10 years imprisonment. (Notably, the prosecutor's closing argument had also focused on March 13 and 14, not explicitly re-emphasizing the March 12 date for this specific plotting.)

- High Court Judgment – A Shift in Findings:

The defendant appealed. The High Court, after hearing new evidence regarding X's alibi, accepted the alibi for the night of March 13, concluding the trial court had erred in rejecting it. This seemingly undermined the core of the prosecution's case as presented and litigated.- However, the High Court then found that the "First Meeting," which the trial court had placed on the night of March 13, actually took place on the night of March 12 at the "Shiratori" coffee shop, and that X had participated in this March 12 meeting. It further found that discussions continued on the daytime of March 13 and on March 14 with X's involvement.

- Based on this revised timeline, the High Court still affirmed X's guilt as a co-conspirator in the hijacking. It reasoned that the trial court's factual error regarding the date of the First Meeting did not affect the ultimate conclusion of guilt. (It did, however, reduce the sentence to 8 years on other grounds).

- Crucially, the prosecution at the High Court had focused on defending the trial court's finding of a March 13/14 conspiracy and attacking the alibi evidence; they had not advanced any new argument that the key meeting occurred on March 12. The High Court also had not alerted the parties that it was considering this alternative date for the First Meeting.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Procedural Foul for "Trial by Surprise"

The Supreme Court found a serious procedural flaw in how the High Court reached its conclusion, even though it ultimately dismissed the defendant's appeal on other substantive grounds related to the overall evidence of conspiracy.

The Court's Reasoning on the Procedural Error:

- Shared Understanding of the Central Issue: The Supreme Court noted that throughout both the first instance and the appeal, both the prosecution and the defense, as well as both courts, had operated under the "fundamental understanding" that X's criminal liability hinged on whether he participated in concrete hijacking plotting with Red Army Faction leaders between his return to Tokyo on March 12 and his arrest on March 15. Within this, the alleged meeting on the night of March 13 at the "Shiratori" coffee shop (the First Meeting) was recognized by all as having particularly crucial significance.

- Duty to Clarify Shifting Focus: When the High Court, unlike the trial court, accepted X's alibi for the night of March 13 but then sought to establish the First Meeting as having occurred on the night of March 12 instead (a date not focused on by the prosecution at the High Court, nor specifically litigated by the defense regarding this particular meeting's alleged content):

- It was incumbent upon the High Court, at the very least, to make the existence of a March 12 meeting a clear and distinct issue of contention (sōten to shite kenzaika saseta ue de) in the appeal and to conduct sufficient deliberation on that point.

- The High Court's failure to take such steps, and its "abrupt" (sotsuzen to shite) finding that the First Meeting actually occurred on March 12 and that X participated, after accepting his alibi for the March 13 date, constituted a "trial by surprise" (fuiuchi) that unjustly infringed upon the defendant's right to defense and was therefore illegal.

However, No Reversal on This Ground Alone:

Despite finding this serious procedural illegality, the Supreme Court did not quash the High Court's judgment on this ground.

- It went on to state that even disregarding the High Court's contested finding about the "First Meeting" (whether on March 12 or 13), a comprehensive review of other evidence on record (X's leadership role in the "Long March Army" intended for overseas operations, his involvement in weapons and funding, Tamiya's detailed report to Shiomi on March 9 about the North Korea hijacking plan, X's actions like writing a letter for funds and briefing members after their selection by Shiomi between March 12-14, and the actions of the hijackers after X's arrest leading up to the actual hijacking using weapons X helped procure) was sufficient to infer X's participation in the concrete hijacking plot by March 14.

- Therefore, the procedural error, while significant, was not deemed to be so prejudicial as to require quashing the judgment when the overall evidence still supported the conclusion of guilt within the scope of the facts generally argued by the prosecution and found by the lower courts (i.e., a conspiracy formed by March 14).

Analysis and Implications: The "Manifestation of Issues" (争点顕在化措置) Doctrine

This 1983 decision in the Yodo-go Hijacking appeal is a landmark ruling on the court's duty to ensure fairness when its line of reasoning shifts from the primary focus of the trial.

- Preventing "Trial by Surprise": The core principle established is that courts cannot "surprise" a defendant by convicting them based on a factual theory or a critical factual finding that was not a central part of the litigation and which the defendant, therefore, had no fair opportunity to contest.

- Duty of "Manifestation of Issues" (Sōten Kenzaika Sochi): If a court (especially an appellate court re-evaluating facts) intends to depart significantly from the commonly understood central issues of the case and rely on a different key factual finding, it has a duty to "manifest" this new point of contention to the parties. This means alerting them to the court's new line of inquiry so that they can present arguments and, if necessary and permissible, evidence related to it.

- The PDF commentary (by Prof. Akira Kidani, in

ksa25.pdf, labeled A26) explains that while the conspiracy itself is part of the "facts constituting the offense" (tsumi to narubeki jijitsu), the specific date and time of a conspiratorial meeting are generally not considered part of the soin that needs to be strictly proven as charged (referencing another Grand Bench decision, Showa 33.5.28). Therefore, a court finding that a meeting occurred on a different date than primarily alleged by the prosecution doesn't automatically require a formal amendment of the indictment (soin henkō). - However, as this case demonstrates, if a particular alleged meeting (like the "First Meeting" on March 13) has become the de facto central battleground of the trial, and the court intends to shift the focus to a different alleged meeting (March 12) that was not similarly litigated, this requires the sōten kenzaika measure to ensure the defendant is not unfairly prejudiced.

- The PDF commentary (by Prof. Akira Kidani, in

- Procedural Fairness Over Substantive Re-evaluation (in this instance): While the Supreme Court ultimately found enough other evidence to uphold the conviction, its detailed condemnation of the High Court's procedural shortcut in shifting the date of the "First Meeting" is a strong statement about the importance of procedural fairness and the defendant's right to a focused defense.

- Balancing Judicial Inquiry and Adversarial Rights: The decision reflects the balance a court must strike. While courts are seekers of truth, in an adversarial system, their inquiry must be conducted in a way that respects the parties' right to know what issues are critical and to present their case accordingly.

Conclusion

The 1983 Supreme Court decision in the Yodo-go Hijacking appeal, while ultimately upholding the defendant's conviction on broader grounds, established a vital procedural safeguard. It mandates that if a court intends to base its judgment on a factual point that significantly diverges from the central issues litigated by the parties, it must first make that new point a clear issue of contention, allowing the defendant a fair opportunity to address it. This "duty to manifest issues" prevents "trial by surprise" and ensures that the defendant's right to an effective defense is not undermined by unexpected shifts in the court's factual findings, particularly in complex conspiracy cases where the specific details of meetings and agreements can be critical.