Trespass in Plain Sight: A Japanese Ruling on Entering Public Spaces with Criminal Intent

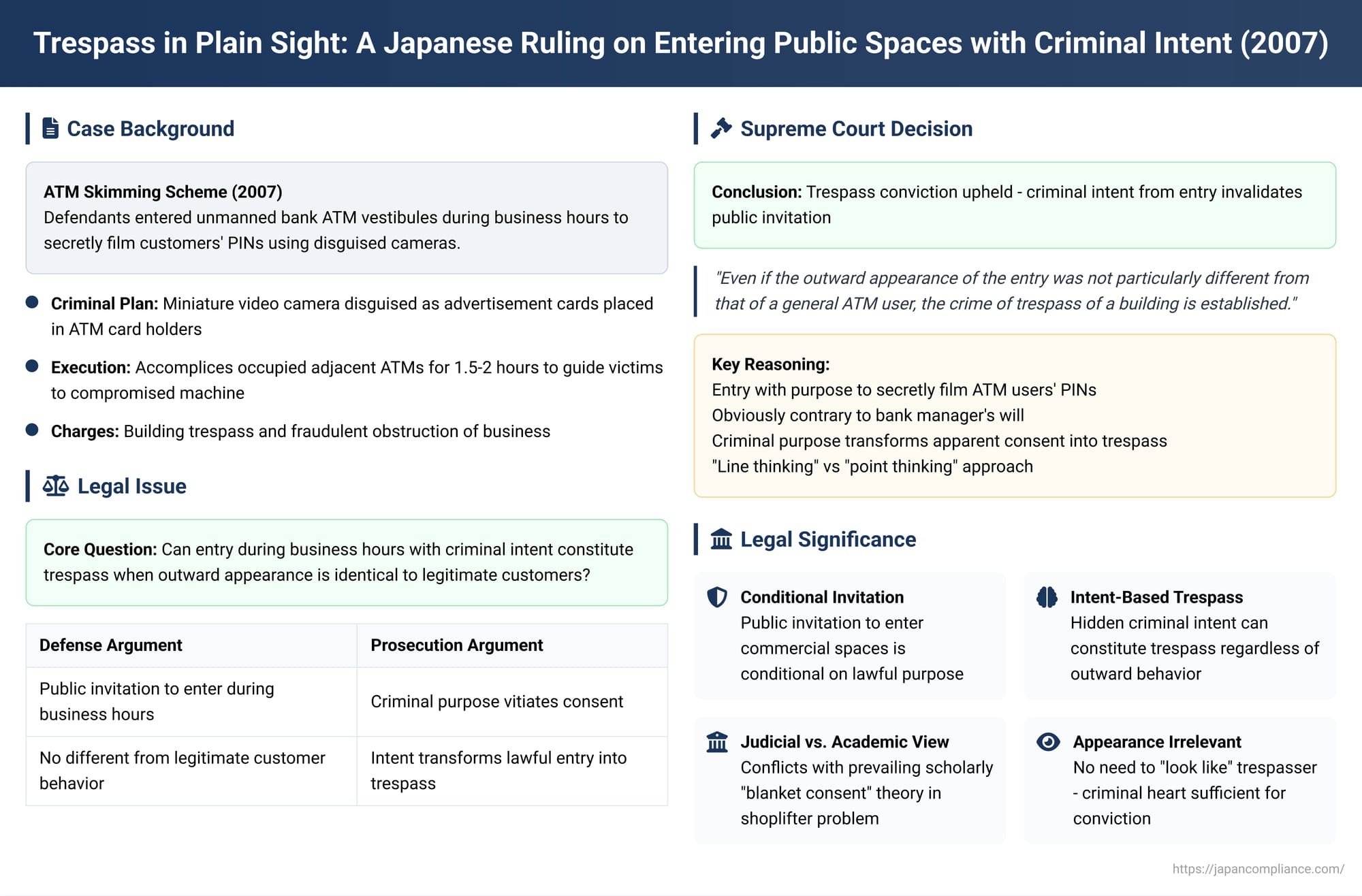

Can a person commit criminal trespass by simply walking through the open doors of a business during business hours? On the surface, the act seems innocuous, identical to that of any legitimate customer. However, if that person harbors a hidden criminal intent, does the very act of entry become a crime? This complex legal question was the subject of a definitive ruling by the Supreme Court of Japan on July 2, 2007. The case, involving a sophisticated scheme to steal bank card information from ATMs, clarified that in Japan, an illicit purpose alone is enough to transform a seemingly normal entry into a criminal trespass.

The decision is a cornerstone of modern Japanese trespass law, demonstrating that the implied invitation for the public to enter a commercial space is conditional. When a person enters with an intent that is fundamentally hostile to the purpose for which the space is held open, they are a trespasser from the moment they cross the threshold, regardless of their outward appearance.

The Facts: A High-Tech Heist in an ATM Vestibule

The case revolved around a criminal conspiracy to steal bank customer data. The defendant and his accomplices devised a detailed plan to surreptitiously film the personal identification numbers (PINs) and other details of customers using Automated Teller Machines (ATMs).

Their targets were unmanned bank branch annexes—publicly accessible vestibules containing multiple ATMs but no permanent staff. The plan, as detailed in the court record, was as follows:

- The Device: The conspirators used a miniature video camera disguised as a stack of advertisement cards. This device was designed to be placed inside the standard advertising card holder present on the bank's ATMs.

- The Setup: Upon entering a target ATM vestibule, one accomplice would place the disguised camera on one of the ATMs. The camera transmitted its video feed wirelessly to a receiver hidden in a paper bag. This bag was then placed on the floor near an adjacent ATM.

- The Ruse: To avoid arousing suspicion and to subtly guide customers toward the ATM with the hidden camera, other accomplices would occupy the adjacent machine (the one with the paper bag). They would pretend to be ordinary customers, performing random operations for an extended period, thereby making the machine unavailable and encouraging new arrivals to use the compromised one.

- Execution: The group successfully executed this scheme on two separate occasions. On the first day, they entered an ATM vestibule with six machines and occupied one for over 1 hour and 30 minutes. The following day, they repeated the act at another location with two ATMs, occupying one for approximately 1 hour and 50 minutes.

The defendant was charged as a co-principal for two crimes: trespass of a building and fraudulent obstruction of business.

The Legal Question: When is an Invitation Not an Invitation?

The central legal issue was the charge of trespass. The ATM vestibules were open to the public during business hours, representing an implied invitation from the bank for customers to enter and use the machines. The defendant and his accomplices did not force their way in, nor was their outward appearance different from that of any other customer. How, then, could their entry be considered a criminal trespass?

A secondary, though undisputed, issue was whether an unmanned vestibule qualified as a "guarded" building as required by the trespass statute. The commentary on the case notes that despite the lack of on-site staff, features like automatic doors controlling access and the presence of security cameras are sufficient to establish that the premises are under the factual management and control of the bank, thus satisfying the "guarded" requirement.

The Supreme Court's Unambiguous Ruling

The Supreme Court upheld the trespass conviction, rejecting the defendant's appeal. The court's reasoning was direct and unambiguous, focusing entirely on the defendant's criminal purpose.

The Court stated that the defendant entered the bank vestibule with the clear "purpose of surreptitiously filming ATM users' card PINs". It then declared that it is "obvious that such an entry is contrary to the will of the bank branch manager," who holds the authority to manage the premises.

The decision's most critical passage directly addresses the defendant's seemingly normal behavior:

"...even if the outward appearance of the entry was not particularly different from that of a general ATM user, the crime of trespass of a building is established".

With this statement, the Court confirmed that a person's hidden, malicious intent can vitiate the general consent granted to the public, making the act of entry itself a crime.

The Great Debate: Trespass by Intent vs. The Prevailing Scholarly View

The Supreme Court's decision, while clear, stands in fascinating contrast to the prevailing view among many Japanese legal scholars, best illustrated by the classic "shoplifter problem."

The academic thought experiment is as follows: A person enters a department store during business hours with the secret intent to shoplift. Is the act of entering the store a trespass?

- The Prevailing Scholarly View (Anti-Trespass): The majority of legal academics argue that this is not a trespass. Their reasoning is based on the concept of "blanket consent". A retail store, as part of its business strategy, extends a general and comprehensive invitation to the public to enter. A manager at the door could not detect the hidden intent and would permit the entry. Therefore, the entry itself is within the scope of this blanket consent. The crime occurs later, with the act of theft, which is a separate offense.

- The Court's View (Pro-Trespass): The Supreme Court's 2007 ruling, along with a consistent line of similar cases, clearly diverges from this scholarly consensus. The judiciary's approach is based not on blanket consent, but on the manager's reasonable will. A reasonable store manager, if they knew a person's intent was to steal, would never consent to the entry. The Court effectively reasons that the criminal purpose retroactively invalidates the consent.

This judicial approach is often described as "line thinking" as opposed to "point thinking". Rather than judging the act of entry in isolation at a single point in time, the Court considers the entry as the first step in a continuous line of criminal conduct. The illicit purpose and the subsequent criminal acts are used to characterize the initial entry as being against the manager's will from the very beginning.

This logic aligns with past rulings where, for example, individuals who entered government buildings peacefully but with the intent to commit acts of protest or violence were convicted of trespass. The Court is less concerned with the theoretical purity of when consent is given or revoked, and more with the pragmatic reality that the entry was an indispensable part of a criminal or disruptive plan.

Conclusion: The Conditional Invitation

The 2007 Supreme Court decision solidifies a broad and pragmatic interpretation of criminal trespass in Japan. It establishes that the invitation for the public to enter a commercial space is conditional, predicated on the assumption of a lawful or at least non-hostile purpose. When an individual enters a space with an intent that is fundamentally at odds with the reason the space is held open—such as to commit crimes against the business or its customers—that individual violates the reasonable will of the manager.

This ruling confirms that, in the eyes of Japanese law, an intruder does not need to look like one. Even an entry that is peaceful, quiet, and outwardly indistinguishable from that of a legitimate customer constitutes a criminal trespass if it is undertaken with a criminal heart. The illicit purpose pierces the veil of implied consent and makes the act of crossing the threshold itself a punishable offense.