Trapped: How Japan's Supreme Court Linked a Trunk Confinement to a Fatal Crash

Case Number: 2005 (A) No. 2091

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Date of Decision: March 27, 2006

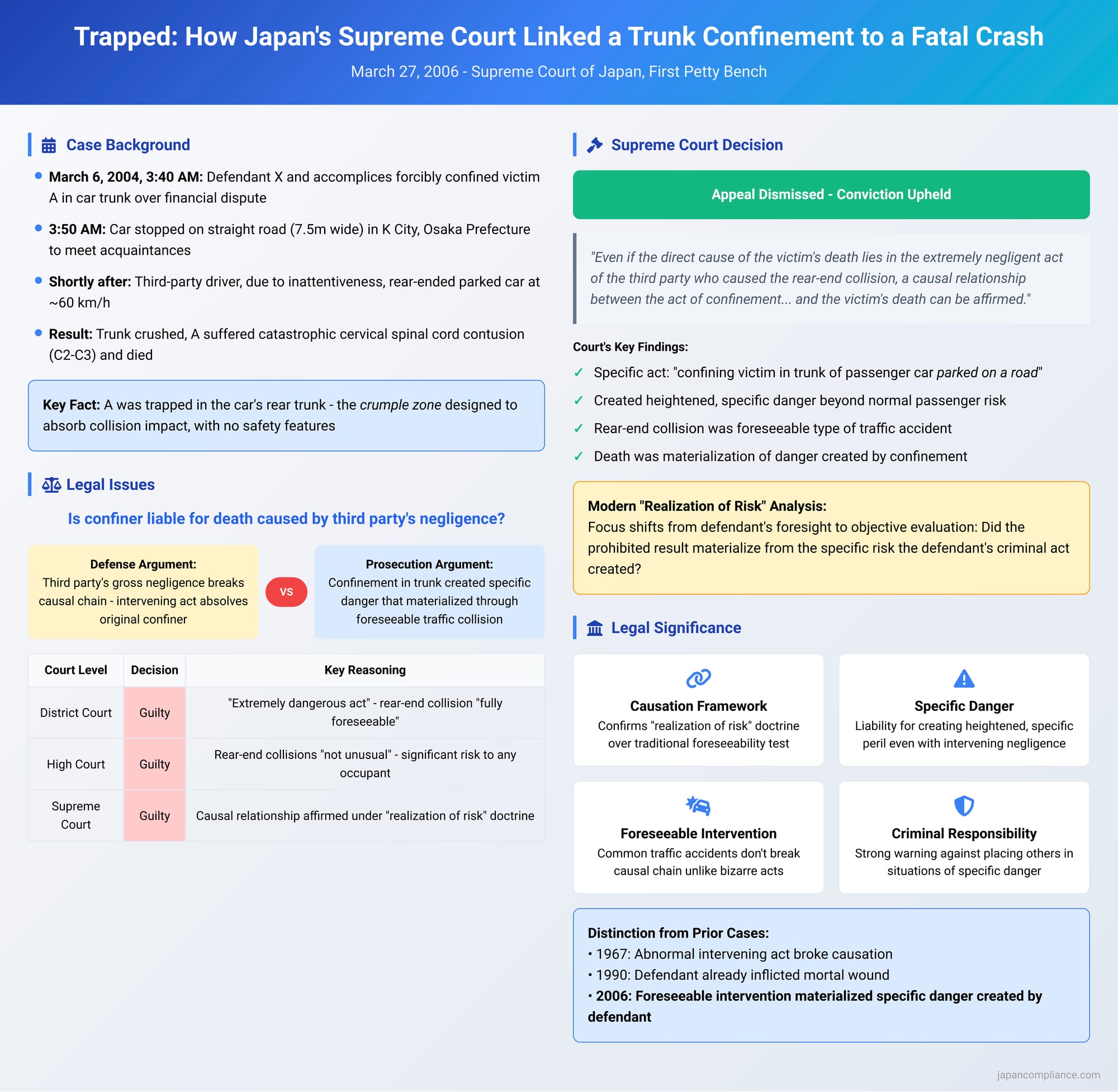

In a case that highlights the grave dangers of unlawful confinement, the Japanese Supreme Court tackled a difficult question of criminal causation: If a person is criminally confined in a car's trunk, and that car is subsequently struck by a negligent third-party driver, leading to the confined person's death, is the original perpetrator of the confinement legally responsible for the death? The Court's 2006 decision provides a powerful affirmation that creating a situation of specific and heightened danger makes one liable for the foreseeable materialization of that danger, even when the immediate trigger is the gross negligence of another.

A Financial Dispute and a Fatal Decision: The Facts of the Case

The case stemmed from a financial dispute between the defendant, X, and the victim, A. On March 6, 2004, at approximately 3:40 AM, the defendant, along with two co-conspirators, Y and Z, decided to take matters into their own hands. The three men grabbed A, forcibly shoved him into the rear trunk of a passenger car, and closed the lid, making escape impossible.

They began driving, but after a short time, they stopped the car on a road in K City, Osaka Prefecture, to meet up with other acquaintances they had called. The location where they stopped was a straight, one-lane road with good visibility, approximately 7.5 meters wide.

A few minutes after stopping, at around 3:50 AM, another passenger car approached from behind. The driver of this second car, due to inattentiveness, failed to notice the parked vehicle until it was too late. The second car slammed into the rear of the parked car at a speed of approximately 60 km/h.

The force of the collision crushed the trunk where A was confined. A suffered a catastrophic cervical spinal cord contusion (at the C2 and C3 levels) and died shortly thereafter from this injury.

The Lower Courts' Path to Conviction

The defendant and his co-conspirators were charged with unlawful arrest and confinement resulting in death (taiho kankin chishi), an aggravated result crime under Article 221 of the Japanese Penal Code.

The first instance court (Osaka District Court, decision dated December 24, 2004) found the defendants guilty. Its reasoning focused on the inherent danger of the defendants' actions. It noted that a car trunk is not designed to hold a person and that confining someone there while driving on a public road is an "extremely dangerous act." The court concluded that it was "fully foreseeable," based on common experience, that a car parked on a road could be struck from behind by a negligent driver, leading to the death of a person trapped in the trunk. It found a direct causal link between the confinement and the death.

The appellate court (Osaka High Court, decision dated September 13, 2005) upheld the convictions. Its reasoning was slightly broader, stating that in rear-end collisions, any occupant of the front car, regardless of where they are situated, faces a significant risk of death or injury. Because such collisions are not unusual, the court found the causal link to be present.

The defendant X alone appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation: Defining the Scope of Risk

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal and upheld the conviction. In its ruling, the Court exercised its own authority (shokken) to clarify the legal basis for its decision, providing a precise and powerful statement on causation:

"Under the facts of this case, even if the direct cause of the victim's death lies in the extremely negligent act of the third party who caused the rear-end collision, a causal relationship between the act of confinement in this case—confining the victim in the trunk of a passenger car parked on a road—and the victim's death can be affirmed."

The Court's wording is crucial. It did not merely affirm causation between "confinement" and "death." It specifically identified the culpable act as "confining the victim in the trunk of a passenger car parked on a road." This precision highlights that the entire situation created by the defendant—the confinement in a dangerous space and the placement of that space in a zone of foreseeable traffic danger—formed the basis of liability.

Legal Analysis: The Modern Doctrine of "Realization of Risk"

This 2006 decision is a clear example of the modern "realization of risk" (kiken no genjitsuka) framework that has come to dominate Japanese causation jurisprudence.

1. The Evolution of Causation - Beyond Foreseeability

While the lower courts used language reminiscent of the traditional "adequate causation theory" (focusing on "foreseeability"), the Supreme Court's approach reflects a more modern analysis. Instead of asking what an actor could have foreseen at the time of the act, the "realization of risk" theory looks back at the entire causal chain and asks whether the prohibited result was a materialization of the specific type of danger that the defendant's criminal act created.

2. The Inherent Danger of the Defendant's Act

The cornerstone of the Supreme Court's reasoning is the exceptionally high level of danger inherent in the defendant's specific act. Confining a person in a car is one thing; confining them in the trunk is another level of danger entirely. A car's trunk:

- Is the rear crumple zone, designed to absorb impact in a collision.

- Lacks any safety features like seatbelts, airbags, or reinforced passenger cell construction.

- Offers the occupant no way to brace for impact or protect themselves.

By placing A in the trunk and then stopping the car on a public road (especially at night), the defendant created a specific and grave risk: that A would suffer severe injury or death from a traffic collision, a danger far exceeding that faced by a person in the passenger cabin.

3. Analyzing the Intervening Act

The analysis of the third-party driver's actions is also critical.

- Was the Act "Abnormal"? Unlike the bizarre intervening act in the 1967 "Serviceman" case (a passenger pulling a victim off a moving car's roof), a rear-end collision caused by an inattentive driver is, unfortunately, a common and foreseeable type of traffic accident. It was not a freak or abnormal event but a known risk of being on a road.

- Contribution to the Result: The third party's gross negligence was undoubtedly the direct cause of death. However, this ruling powerfully demonstrates that in Japanese law, the existence of a direct cause does not automatically negate the causal responsibility of a prior actor who created the underlying perilous condition. Multiple actors can have a legally relevant causal link to the same result.

4. Realization of a Foreseeable Risk

Synthesizing these points leads to a clear conclusion under the "realization of risk" framework.

- The Risk Created: The defendant's act of confining A in the trunk of a car parked on a road created a specific, heightened risk of death from a rear-end collision.

- The Result: A rear-end collision occurred, causing A's death.

- Conclusion: The tragic result was the very materialization of the specific risk the defendant had culpably created. The death was not an unpredictable fluke; it was the direct fulfillment of the danger inherent in the defendant's criminal enterprise.

Comparison with Prior Landmark Cases

This 2006 ruling fits logically within the Supreme Court's evolving jurisprudence on causation:

- It stands in contrast to the 1967 "Serviceman" case, where a highly abnormal and unforeseeable intervening act broke the chain of causation.

- It is distinct from the 1990 "Osaka South Port" case, where the defendant had already inflicted the mortal wound and the intervening act merely hastened the inevitable.

- This case carves out a third category: where the defendant's act creates a highly dangerous situation, and a foreseeable type of intervening act (even a grossly negligent one) triggers the materialization of that specific danger, the causal link remains intact.

Conclusion

The 2006 "Confinement in Car Trunk" case is a powerful modern statement on criminal causation in Japan. It serves as a stark warning that those who place others in a situation of specific and heightened peril will be held responsible for the predictable consequences. The Supreme Court's decision illustrates that the focus of modern causation analysis is less on the subjective foresight of the defendant and more on an objective evaluation of the nature of the risk their criminal conduct unleashes upon the world. When that specific risk materializes, even through the negligent hands of another, the original architect of the danger cannot escape legal responsibility for the fatal outcome.