Transgender Parentage in Japan: Supreme Court Affirms Presumption of Legitimacy for Child Born via Donor Insemination

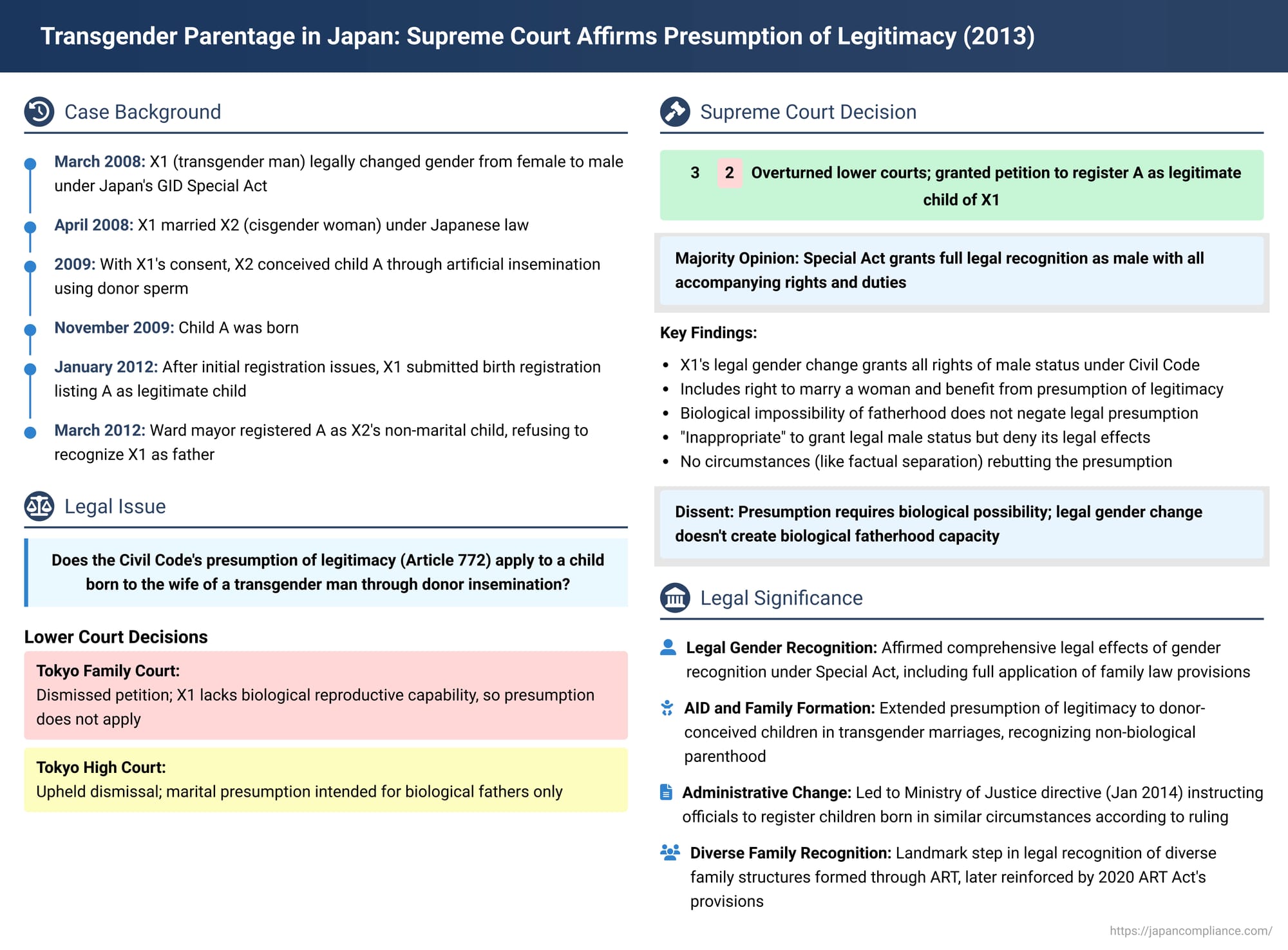

Date of Decision: December 10, 2013, Supreme Court of Japan (Third Petty Bench)

The evolving understanding of gender identity and advancements in assisted reproductive technologies (ART) present ongoing challenges to traditional legal frameworks of family and parentage. A landmark Japanese Supreme Court decision on December 10, 2013, addressed a deeply personal and legally complex issue: the legal status of a child born to the wife of a transgender man (female-to-male) through artificial insemination by a donor (AID). This case sits at the intersection of transgender rights, family law, and the legal recognition of families formed through ART.

The Facts: A Family's Journey and a Legal Challenge

The case involved X1, who was assigned female at birth but was diagnosed with Gender Identity Disorder (GID). After undergoing sex reassignment surgery, X1 obtained a court ruling in March 2008, officially changing his legal gender to male. This change was made pursuant to Japan's "Act on Special Cases in Handling Gender Status for Persons with Gender Identity Disorder" (commonly known as the 特例法 - Tokureihō, or "Special Act"). X1's official family register (koseki) was updated to reflect this legal gender change.

In April 2008, X1, now legally male, married X2, a woman. Subsequently, X2, with X1's consent, conceived a child, A, through artificial insemination using sperm from a donor other than X1. Child A was born in November 2009.

X1 initially attempted to register A as the legitimate child of both himself and X2 with the B City Mayor. This registration was not accepted, reportedly due to perceived deficiencies in the submitted documents. After changing their registered family domicile, X1 submitted a new birth registration for A as their legitimate child to the C Ward Mayor in January 2012.

The C Ward Mayor, however, after requesting corrections to the birth registration (which X1 did not provide as requested), registered child A in March 2012 in a manner that did not recognize X1 as the father. Specifically, the father column for A was left blank, and A was recorded as X2's first son (effectively, as X2's non-marital child). This registration was made with the permission of the Director of the Tokyo Legal Affairs Bureau.

X1 and X2 challenged this registration. They filed a petition seeking a correction of the family register under Article 113 of the Family Register Act. Their core argument was that child A should be presumed to be the legitimate child of X1 and X2 under Article 772 of the Japanese Civil Code. They requested that X1 be listed as A's father and that the entries indicating A's non-marital status be removed and replaced with details consistent with a legitimate birth registration by the father.

Lower Courts: Denying Legitimacy

The lower courts sided against X1 and X2:

- Tokyo Family Court: Dismissed the petition. The court reasoned that X1's own family register entry, which documented the legal gender change under the Special Act, made it objectively clear that X1, having been born female, lacked male biological reproductive capability. Therefore, the court concluded, child A could not be presumed to be X1's legitimate child under Civil Code Article 772. The ward mayor’s action in registering A as a non-marital child was deemed within the scope of his authority and consistent with objective facts.

- Tokyo High Court: Upheld the Family Court's dismissal. The High Court elaborated that legitimate parent-child relationships under Japanese law are fundamentally based on biological ties within the context of marriage. Civil Code Article 772, which presumes a child conceived by a wife during marriage to be the husband's child, is intended to maintain family peace, protect marital privacy, and ensure the swift stabilization of the father-child relationship. The High Court found that where it is evident from the family register itself (due to the record of gender change under the Special Act) that the husband cannot be the biological father, the very premise for applying Article 772 is absent. Registering A as a non-marital child was, therefore, not deemed a violation of constitutional rights (under Articles 13 or 14 of the Constitution).

X1 and X2 appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Landmark 3-2 Decision (December 10, 2013)

In a closely divided 3-2 decision, the Supreme Court overturned the rulings of the High Court and the Family Court. It granted X1 and X2's petition and ordered the family register to be corrected to list X1 as A's father and to reflect A's status as the legitimate child of the couple.

Key Reasoning of the Majority:

- Full Legal Recognition as Male: The majority began by affirming the comprehensive effect of the Special Act. Article 4, paragraph 1, of the Special Act stipulates that a person who has received a court ruling changing their legal gender is, for the application of the Civil Code and other laws, deemed to have changed to the other gender, unless specific laws provide otherwise. Consequently, X1, having legally become male, is treated as male for all legal purposes.

- Marriage and Presumption of Legitimacy: As a legally recognized male, X1 was entitled to marry a woman (X2) as her husband under the Civil Code. The Supreme Court then held that if the wife of such a legally recognized husband conceives a child during the marriage, that child is presumed to be the husband's child under Article 772 of the Civil Code.

- Addressing Biological Impossibility and Distinguishing from Precedents: The Court acknowledged its own precedents where the presumption of legitimacy under Article 772 is held not to apply. These are typically cases where, for example, at the presumed time of conception, the husband and wife were factually divorced and living separate lives, or were living so far apart that any sexual relationship between them was impossible. These exceptions are often referred to as cases involving a "child to whom the presumption does not reach" (推定の及ばない子 - suitei no oyobanai ko).However, the majority distinguished the present case. While conceding that for a person who has undergone a female-to-male gender transition, conceiving a child through sexual relations with their wife is "unthinkable" (およそ想定できない - oyoso sōtei dekinai), they found it "inappropriate" (相当でない - sōtō de nai) to, on one hand, legally permit such individuals to marry as men, and then, on the other hand, deny them a primary legal effect of marriage—the presumption of legitimacy for a child born to their wife—solely on the ground that the child could not have been conceived as a result of sexual relations with that husband. The legal status conferred by the marriage and the Special Act took precedence over the biological impossibility of X1 fathering a child through coitus.

- Application to Child A's Case: Child A was conceived by X2 while she was legally married to X1. Therefore, even though X1 is a transgender man who had his legal gender changed under the Special Act, A is presumed to be X1's child pursuant to Civil Code Article 772. The Court found no other circumstances that would typically rebut this presumption, such as evidence that the couple's marital relationship had broken down to the point where they were effectively living as if divorced.

Consequently, the Supreme Court concluded that X1 and X2 should be permitted to register A as their legitimate child. The C Ward Mayor's registration of A as X2's non-marital child, based on the reasoning that A was not presumed legitimate by X1, was therefore deemed legally impermissible.

Dissenting Opinions: Emphasis on Biological Reality

The two dissenting justices argued against the majority's conclusion. Their primary contention was that X1's biological inability to father a child was an objective and undeniable fact, stemming from the requirements of the Special Act itself (which includes the permanent absence of the reproductive glands of the original sex). Since the presumption of legitimacy under Civil Code Article 772 is fundamentally rooted in the possibility of the husband biologically fathering a child through marital relations, the dissent argued that this presumption should not apply where such biological fatherhood is patently impossible due to the husband's transgender status and the conditions under which legal gender change was granted. One dissenting opinion also expressed concern that the majority's interpretation was effectively stepping into the domain of regulating parentage in assisted reproduction without a clear legislative framework, potentially setting a problematic precedent.

The Legal Framework: Presumption of Legitimacy and Its Exceptions

- Civil Code Article 772: This article is central to Japanese family law regarding paternity.

- Paragraph 1: A child conceived by a wife during marriage is presumed to be the child of the husband.

- Paragraph 2: A child born 200 days or more after the date of marriage, or within 300 days from the day of dissolution or annulment of the marriage, is presumed to have been conceived during the marriage.

- This presumption is robust and can traditionally only be overturned by the husband through a formal action to deny paternity (嫡出否認の訴え - chakushutsu hinin no uttae), which must be filed within one year of his learning of the child's birth (Civil Code Articles 774, 775, 777). The right to deny paternity is lost if the husband acknowledges the child as his own after birth (Article 776).

- "Child Not Reaching Presumption": Japanese case law and legal scholarship have developed a concept of "a child to whom the presumption does not reach." This applies in situations where, despite the timing of the birth falling within the statutory periods, it was objectively impossible for the wife to have been impregnated by her husband (e.g., due to prolonged physical separation, imprisonment, etc.). In such cases, the presumption does not apply, and legal challenges to paternity (e.g., a suit for determination of the existence or non-existence of a parent-child relationship) can be brought by interested parties without the strict one-year time limit.

Theories on when this exception applies have varied, with the Supreme Court generally favoring an "exterior appearance theory," focusing on externally obvious facts like a complete lack of cohabitation. The majority in the 2013 decision chose not to extend this exception based purely on the biological infertility of the transgender husband within an otherwise intact marriage, given the legal recognition of his male status and his marriage.

One of the supplementary opinions supporting the majority (by Justice Kiuchi) argued that the fact of X1's gender change under the Special Act, while a legal reality, is not necessarily an "obvious" fact to third parties in the same way that, for instance, a husband's long-term absence abroad would be. Thus, it should not serve as a basis for excluding the presumption under the traditional "exterior appearance" criteria for such exceptions.

Context: AID and Parentage in Japan

The use of Artificial Insemination by Donor (AID) has its own history of legal discussion in Japan, even before cases involving transgender parents arose.

- Where a married woman undergoes AID with her husband's consent, the prevailing view in legal scholarship and some lower court precedents (e.g., a Tokyo High Court decision, September 16, 1998) has been that the resulting child is presumed to be the legitimate child of the consenting husband under Civil Code Article 772.

- This case involving X1 brought a new dimension to the AID discussion by intersecting it with legal gender recognition. The dissenting opinions expressed concern about the implications of the majority's decision for the broader, and still developing, legal framework for children born via various forms of assisted reproduction.

Impact of the Decision and Subsequent Developments

- Change in Koseki Practice: Following this Supreme Court ruling, the Ministry of Justice issued a new directive (Minji Ichidai No. 77, dated January 27, 2014) to family registration officials. This directive instructed them to handle birth registrations for children born in similar circumstances in accordance with the Supreme Court's decision, meaning that a transgender man legally married to the birth mother can be registered as the father of a child born to her via AID during the marriage.

- 2020 ART Act: In December 2020, Japan enacted the "Act on Special Provisions to the Civil Code Concerning Parent-Child Relationships with Regard to Assisted Reproductive Technology Provided by a Third Party and Other Related Matters" (often referred to as the ART Act). While this Act does not specifically address parentage for transgender individuals, Article 10 (which came into effect in December 2021) is relevant to AID. It stipulates that if a wife gives birth to a child conceived through assisted reproduction using sperm from a donor other than her husband, with the husband's consent, the husband cannot subsequently deny that the child is his legitimate child. This reinforces the legal recognition of non-biological fatherhood within marriage where there is consent to AID.

- Ongoing Legislative Review: The 2020 ART Act also includes provisions for a review of related legal issues within approximately two years. Furthermore, a February 2022 draft proposal from the Legislative Council of the Ministry of Justice concerning revisions to parent-child law suggests amending Article 10 of the ART Act. The proposed change would mean that in cases of consented AID, not only the husband but also the wife and the child would be barred from denying the child's legitimacy as the husband's child. This indicates that Japanese family law concerning assisted reproduction is still an area of active development and reform.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's 2013 decision in the case of X1, X2, and A was a groundbreaking moment for the legal recognition of families headed by transgender individuals in Japan. By giving precedence to the legal status conferred by the Special Act for Gender Identity Disorder and the ensuing legal marriage, the 3-2 majority affirmed that a child born to the wife of a transgender man via donor insemination is presumed to be the legitimate child of that transgender man under Civil Code Article 772.

This ruling prioritized the legal effects and social realities of marriage and recognized gender identity over a strict insistence on biological reproductive capacity as the sole basis for applying the presumption of legitimacy in this specific context. While the dissenting opinions highlighted concerns about biological realities and the need for clearer legislative solutions for ART-related parentage, the majority's decision, along with subsequent administrative and legislative developments, signals a significant, albeit evolving, step towards greater inclusion and recognition of diverse family structures within Japanese law. The case underscores the ongoing dialogue and adaptation required as legal systems worldwide grapple with the implications of medical advancements and changing societal norms.